Nigerian nationalism

Nigerian nationalism asserts that Nigerians as a nation should promote the cultural unity of Nigerians.[1][2] Nigerian nationalism is territorial nationalism and emphasizes a cultural connection of the people to the land, particularly the Niger and the Benue Rivers.[3] It first emerged in the 1920s under the influence of Herbert Macaulay, who is considered to be the founder of Nigerian nationalism.[4] It was founded because of the belief in the necessity for the people living in the British colony of Nigeria of multiple backgrounds to unite as one people to be able to resist colonialism.[2][5] The people of Nigeria came together as they recognized the discrepancies of British policy. "The problem of ethnic nationalism in Nigeria came with the advent of colonialism. This happened when disparate, autonomous, heterogeneous and sub-national groups were merged to form a nation. Again, the colonialists created structural imbalances within the nation in terms of socio-economic projects, social development and establishment of administrative centres. This imbalance deepened the antipathies between the various ethnic nationalities in Nigeria (Nnoli, 1980; Young, 1993, and Aluko, 1998)."[6] The Nigerian nationalists' goal of achieving an independent sovereign state of Nigeria was achieved in 1960 when Nigeria declared its independence and British colonial rule ended.[1] Nigeria's government has sought to unify the various peoples and regions of Nigeria since the country's independence in 1960.[1]

Nigerian nationalism has been negatively affected by multiple historical episodes of ethnic violence and repression of certain ethnic groups by the Nigerian government between the various peoples has resulted in multiple secessionist movements demanding independence from Nigeria.[1] However aside from instances of extremism, most Nigerians continue to peacefully coexist with each other, and a common Nigerian identity has been fostered amongst the more-educated and affluent Nigerians as well as amongst the many Nigerians who leave small homogeneous ethnic communities to seek economic opportunities in the cities where the population is ethnically mixed.[7] For instance many southerners migrate to the north to trade or work while a number of northerner seasonal workers and small-scale entrepreneurs go to the south.[8]

History

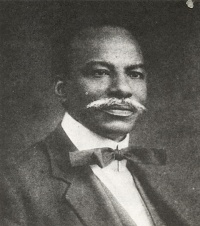

[edit]Herbert Macaulay became a very public figure in Nigeria, and on 24 June 1923 he founded the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), the first Nigerian political party.[9] The NNDP won all the seats in the elections of 1923, 1928 and 1933.[9] In the 1930s, Macaulay took part in organizing Nigerian nationalist militant attacks on the British colonial government in Nigeria.[4] The Nigerian Youth Movement (NYM) founded in 1933 by Professor Eyo Ita was joined in 1936 by Nnamdi Azikiwe that sought support from all Nigerians regardless of cultural background, and quickly grew to be a powerful political movement.[2] In 1944, Macaulay and NYM leader Azikiwe agreed to form the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) (a part of Cameroon was incorporated into the British colony of Nigeria).[10] Azikiwe increasingly became the dominant Nigerian nationalist leader, he supported pan-Africanism and a pan-Nigerian based nationalist movement.[5]

Nigerian nationalism radicalized and grew in popularity and power in the post-World War II period when Nigeria faced undesirable political and economic conditions under British rule.[11] The most prominent agitators for nationalism were Nigerian ex-soldiers who were veterans of World War II who had fought alongside British forces in the Middle East, Morocco, and Burma; another important movement that aided nationalism were trade union leaders.[11] In 1945, a national general strike was organized by Michael Imoudu who along with other trade union figures became prominent nationalists.[11]

However, Nigerian nationalism by the 1940s was already facing regional and ethnic problems to its goal of promoting a united, pan-Nigerian nationalism.[5] Nigerian nationalism and its movements were geographically significant and important in southern Nigeria while a comparable Nigerian nationalist organization did not arrive in northern Nigeria until the 1940s.[5] This regional division in the development and significance of Nigerian nationalism also had political implications for ethnic divide - southern Nigeria faced strong ethnic divisions between the Igbo and the Yoruba while northern Nigeria did not have strong internal divisions, this meant northern Nigeria that is demographically dominated by the Hausa was politically stronger due to its greater internal unity than that of southern Nigeria that was internally disunified.[5] The south that was ethnically divided between the Igbo and the Yoruba, though the region most in favour of Nigerian nationalism; faced the north that was suspicious of the politics of the south, creating the North-South regional cleavage that has remained an important issue in Nigerian politics.[5]

In 1960, Nigeria became an independent country. Azikiwe became the first President of Nigeria. However, ethnic tensions and power struggles soon emerged and became a crisis in 1966 when Nigerian military officers of Igbo descent overthrew the democratically elected government of Tafawa Balewa who along with the Northern Premier Ahmadu Bello and others were subsequently assassinated.[12] The killing of Northern politicians enraged Northerners resulting in violence against the Igbo by northerners.[12] The military government sought to end the ethnic unrest by dismantling the federal system of government and replacing it with a unitary system of government, however this reform was short-lived as the government was overthrown in another coup that saw Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu Gowon become the North’s compromise with the south to lead Nigeria.[12]

By 1967, many Igbos had lost faith in Nigerian nationalism and in May of that year, Igbo separatists formed the Republic of Biafra that demanded secession from Nigeria. The Biafran crisis was the most serious threat to the Nigerian unity since Nigeria became independent in 1960, as other ethnic groups threatened that they too would also seek secession should Biafra successfully secede.[12] Nigeria responded to the separatist threat with a military campaign against the Biafran government, resulting in the Nigerian Civil War from 1967 to 1970.[12] The war ended with the defeat of the Biafran separatists. Between one and three million Nigerians died in the war.[12]

Emergence of political organizations

[edit]The 19th century did not witness the emergence of any political organization that could help in airing the grievances and expressing the aspirations of Nigerians on a constant basis. The British presence in the early 20th century led to the formation of political organizations as the measures brought by the British were no longer conducive for Nigerians. The old political methods practiced in Lagos was seen as no longer adequate to meet the new situation. The first of such organizations was the People's Union formed by Orisadipe Obasa and John K. Randle with the main aim of agitating against the water rate but also to champion the interests of the people of Lagos. This body became popular and attracted members of all sections of community including the Chief Imam of Lagos, as well as Alli Balogun, a wealthy Muslim. The popularity of the organization reduced after it was unable to prevent the imposition of the water rate by 1916. The organization was also handicapped by constant disagreements among the leaders. The emergence of the NCBWA and the NNDP in 1920 and 1923 respectively, led to a major loss of supporters of the People's Union, and by 1926, it had completely ceased to exist. Two years after the formation of the People's Union, another organization called The Lagos Ancillary of the Aborigines Rights Protection Society (LAARPS) came into the picture. This society was not a political organization but a humanitarian body. This organization came into existence to fight for the interest of Nigerians generally but its attention was taken up by the struggle over the land issue of 1912. In Northern Nigeria, all lands were taken over by the administration and held in trust for the people. Those in Southern Nigeria feared that this method would be introduced into the South. Educated Africans believed that if they can be successful in preventing the system from being extended to Southern Nigeria, then they can fight to destroy its practice in the North. This movement attracted personalities in Lagos amongst whom are James Johnson, Mojola Agbebi, Candido Da Rocha, Christopher Sapara Williams, Samuel Herbert Pearse, Cardoso, Adeyemo Alakija and John Payne Jackson (Editor, Lagos Weekly Record). Its delegation to London to present its views to the British government was discredited by quarrels which broke out among its members over the delegation fund. Accusations of embezzlement against some members, disagreements and quarrels, as well as the death of some of its leading members led to the untimely death of this organization before 1920. The outbreak of war and a strong political awareness led to the formation of a number of organizations. These are the Lagos Branch of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the National Congress of British West Africa (NCBWA), and the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP).[13][14]

Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA)

[edit]The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA) was founded in 1914 by Marcus Garvey.[15] The initiatives of Rev. William Benjamin Euba and Rev. S. M. Abiodun led to the formation of a branch in Lagos in 1920.[16] The Lagos branch of the UNIA did not survive long because of the hostility of fellow Nigerians, members of the NCBWA as well as the colonial administration (because of the belief that Garvey's movement was a subversive one). Despite its short span, it was able to serve as an inspiration to men like Ernest Sessi Ikoli (its first secretary) as well as Nnamdi Azikiwe.[17]

National Congress of British West Africa (NCBWA)

[edit]The idea of forming a regional political body such as the National Congress of British West Africa (NCBWA) was initiated by Joseph Casely Hayford and Dr Akinwade Savage.[18] The NCBWA differed in important respects from earlier nationalist movements in the area. The NCBWA envisaged a united British West Africa as a political objective to be attained, unlike the earlier nationalist movements. It was organised on a scale that embraced all four colonies (Gold Coast, Sierra Leone, Nigeria and Gambia) of British West Africa simultaneously, and was led almost exclusively by the educated elite of the area which were mainly successful professional men: lawyers, doctors and clergy with a sprinkling of merchants, journalists and chiefs. [19][20][21][22] The idea of forming this political body seemed impossible because people believed that such a body embracing the whole of British West Africa would be difficult to organize because of political challenges posed by poor communication facilities, different levels of development of the territories that make up British West Africa, as well as the fact there was no tradition of close association in the politics of the four territories.[23][18] Because Hayford owned The Gold Coast Nation newspaper, and it was edited by Akinwande Savage, this body gained wide publicity. Letters were sent to notable men in Lagos, Freetown and Bathurst soliciting their support for the new movement. A conference was convened in 1920 in Accra after the outbreak of the First World War, and it was at this conference that the NCBWA was formed. It was at this conference that the decision to send delegates to the Colonial Office was decided. They had the following demands:[24][18][25][26]

- That a legislative council be established for each of the west African colonies, with half its members elected and half nominated.

- That the appointment and deposition of chiefs be left in the hands of their peoples, not the colonial governors.

- The separation of the executive from the judiciary.

- The abolition of racial discrimination in the civil service and in social life.

- That an appeal court for British West Africa be established.

- That a University for West Africa be established.

- The development of municipal government.

- The repeal of certain "obnoxious" ordinances.

Alongside these requests, they wished the Colonial Office to consider whether the increasing number of Syrians were 'undesirable and a menace to the good Government of the land'.[27] A lengthy petition arising from conference resolutions was submitted to the king. Unfortunately, it obscured central issues and failed to distinguish specific grievances in the different colonies. At a point it was thought that the delegation were seeking self-government. The mandarins at the Colonial Office pointed out inconsistencies and obscurities, while the NCBWA ignored the colonial governors by appealing to London. The delegation that presented the petition were in London from October 1920 to February 1921. They were able to establish contact with the League of Nations Union, the Bureau International pour LA Défense des Indigènes, the Welfare Committee for Africans in Europe, the African Progress Union, and West African students resident in London. While in London, the delegation gained the support of some members of Parliament as well as that of prominent Afrophiles like Sir Sydney Oliver, J.H. Harris and Sir Harry Johnston. Governors Clifford of Nigeria and Guggisberg both denounced the Congress as an unrepresentative body and felt that's the territories we're not matured enough for elective representation. This was also the stand of the Colonial Office. In the Gold Coast legislative council Nana Ofori Atta, the paramount chief of Akyem Abuakwa in the Eastern Province, declared that the chiefs were the rightful spokesmen of the people, and not the congress. The reports of the Governors of the British West Africa territories led to the rejection of the demands of the delegation by Secretary of State, Lord Milner. The delegation encountered some financial difficulties. These problems, alongside tension within the delegation as well as reputation of certain of its members by prominent Africans back home, brought about the death of this group. The Lagos branch of this congress did not accept defeat completely. The fourth session of the congress was held in 1930 in Lagos. Its deliberations attracted considerable attention mainly because of the support of the Nigerian Democratic Party. A deputation from the Lagos section visited the Governor in 1931 with the aim of continuity. They stated that the aim of the congress was to maintain strictly and inviolate the connection of British West African Dependencies with the British Empire.[28] In 1933, J. C. Zizer who was the Secretary of the congress as well as the editor of its weekly organ, West African Nationhood departed and the congress became moribund. In 1947, there were attempts to revive this organization but it proved abortive.[29][26] Despite the early demise, some of their demands were met some few years after the visit to London while some were not met until after two decades such as the establishment of a University for West Africa. One of the successes of this organization was the inclusion of the elective principle in the new constitution worked out by Hugh Clifford in 1922. The grant to the elective representation led to the emergence of well structured political organizations in Nigeria. These organizations paved way for a more organized way for Nigerians express their aspirations and air their grievances likewise. The NNDP and the NYM owe their existence to the NCBWA.[30]

See also

[edit]- Nigeria

- Nigerians

- Culture of Nigeria

- Nationalism

- Territorial nationalism

- Bandele Omoniyi

- Herbert Macaulay

- Eyo Ita

- Nnamdi Azikiwe

- Udo Udoma

- People's Union (Nigeria)

- NCBWA

- NNDP

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Motyl 2001, pp. 372.

- ^ a b c Luke Uka Uche. Mass media, people, and politics in Nigeria. Concept Publishing Company, 1989, pp. 23–24

- ^ Guntram H. Herb, David H. Kaplan. Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2008, p. 1184.

- ^ a b Uche, Mass media, people, and politics in Nigeria, 1989, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f Toyin Falola, Saheed Aderinto. Nigeria, nationalism, and writing history. Rochester, New York, USA: Rochester University Press, 2010, p. 256.

- ^ Aluko, M.A.O (2003). "Ethnic Nationalism and the Nigerian Democratic Experience in the Fourth Republic" (PDF). Anthropologist. 5 (4): 253–259. doi:10.1080/09720073.2003.11890817. S2CID 59246616.

- ^ April A. Gordon. Nigeria's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. Pp. 233.

- ^ Toyin Falola. Culture and Customs of Nigeria. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press, 2001, p. 8.

- ^ a b Webster, Boahen & Tidy 1980, pp. 267.

- ^ Uche, Mass media, people, and politics in Nigeria, 1989. p. 24.

- ^ a b c Guntram and Kaplan. Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview. 2008, p. 1181.

- ^ a b c d e f Guntram and Kaplan. Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview. 2008, p. 1185.

- ^ Olusanya 1980, p. 552.

- ^ Nigerian Chronicle. (1910/09/02). The Nigerian Chronicle, 'News of the Week', p.2. Accessed from (NewsBank/Readex, Database: World Newspaper Archive)

- ^ "Akron's Black History Timeline". akronohio.gov. City of Akron. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Olusanya, Gabriel (1969). "Notes on the Lagos Branch of the Universal Negro Improvement Association". Journal of Business & Social Studies. 1 (2): 135.

- ^ Olusanya 1980, p. 554.

- ^ a b c Olusanya, Gabriel (2 June 1968). "The Lagos Branch of the National Congress of British West Africa". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria. 4.

- ^ Eluwa, G.I.C (September 1971). "Background to the Emergence of the National Congress of British West Africa". African Studies Review. 14 (2): 205–218. doi:10.2307/523823. JSTOR 523823. S2CID 143925097.

- ^ Langley, J. Ayodele (1973). Pan-Africanism and Nationalism in West Africa, 1900–1945, Study in African Affairs. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Falola, Toyin (2001). Nationalism and African Intellectuals. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. pp. 97–180. ISBN 9788210000256.

- ^ Esedebe, P. Olisanwuche (1994). Pan-Africanism: The Idea and the Movement, 1776-1991 (2nd ed.). Washington DC: Howard University Press. pp. 3–94. ISBN 978-0882581866.

- ^ Britannica 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Eluwa, G. I. C (1 January 1971). "The National Congress of British West Africa: a Study in African Nationalism". Présence Africaine. 77: 131–149. doi:10.3917/presa.077.0131.

- ^ Bourne, Richard (2015). Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century (1st ed.). London: Zed Books. pp. 32–38. ISBN 978-1-78032-908-6.

- ^ a b Coleman, James S. (1958). Nigeria: Background to Nationalism. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 169–270. ISBN 9780520020702.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Resolutions of the Conference of Africans of British West Africa. London. 1920.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "West African Nationhood". 7 July 1931.

- ^ "Notes of the National Congress of British West Africa". Macaulay Paper.

- ^ Olusanya 1980, p. 556.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Quran and Quran exegesis", 1974, De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 3–28, 1974-12-31, doi:10.1515/9783112312827-001, ISBN 9783112312827, retrieved 2022-04-19

- Olakunle, Gabriel (January 1, 1980). "Chapter 27: Nationalist Movements". In Ikime, Obaro (ed.). Groundwork of Nigerian History. Ibadan: Heinemann Educational Books (Nigeria) Plc. pp. 545–569. ISBN 978-129-954-1.

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-227230-7.

- Britannica (2010-10-01). The History of Western Africa. Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61530-399-1. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- Webster, James Bertin; Boahen, A. Adu; Tidy, Michael (1980). The revolutionary years: West Africa since 1800. Longman. ISBN 0-582-60332-3.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch