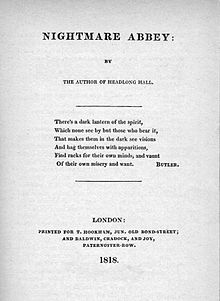

Nightmare Abbey

Title page of the first edition (1818) | |

| Author | Thomas Love Peacock |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Gothic novella, Romance novella, Satire |

| Published | November 1818 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Preceded by | Melincourt |

| Followed by | Maid Marian |

Nightmare Abbey is an 1818 novella by Thomas Love Peacock which makes good-natured fun of contemporary literary trends.

The novel

[edit]Nightmare Abbey was Peacock's third long work of fiction to be published. It was written in late March and June 1818, and published in London in November of the same year. The novella was lightly revised by the author in 1837 for republication in Volume 57 of Bentley's Standard Novels. The book is Peacock's most well-liked and frequently-read work.[1]

The novel was a topical work of Gothic fiction in which the author satirised tendencies in contemporary English literature, in particular Romanticism's obsession with morbid subjects, misanthropy and transcendental philosophical systems. Most of its characters are based on historical figures whom Peacock wished to pillory.[2]

It has been observed that "the plots of Peacock's novels are mostly devices for bringing the persons together and the persons are merely the embodiment of whims and theories, or types of a class".[3] Nightmare Abbey embodies the critique of a particular mentality and pillories the contemporary vogue for the macabre. To his friend Percy Bysshe Shelley, Peacock described the object of his novel as being "to bring to a sort of philosophical focus a few of the morbidities of modern literature". Appearing in the same year as Northanger Abbey, it similarly contrasts the product of the inflamed imagination, or what Peacock's Mr Hilary describes as the "conspiracy against cheerfulness", with the commonplace course of everyday life, with the aid of light-hearted ridicule.[4]

Several of the chapters take a dramatic form interspersed with stage directions in order to illustrate without comment how much the speakers characterise themselves through their conversation. The actor and director Anthony Sharp was eventually to take this approach to its logical conclusion and reduced the whole novel to a successful and popular script. First performed in February 1952,[5] it was eventually published in 1971.[6]

Plot

[edit]Insofar as the novel may be said to have a plot, it follows the fortunes of Christopher Glowry, a morose widower who lives with his only son Scythrop in the isolated family mansion, Nightmare Abbey, in Lincolnshire. Mr Glowry's melancholy leads him to choose servants with long faces or dismal names such as Mattocks, Graves and Skellet. The few visitors he welcomes to his home are mostly of a similar cast of mind, with the sole exception of his brother-in-law, Mr Hilary. The visitors engage in conversations, or occasionally monologues, which serve to highlight their eccentricities or obsessions.

Mr Glowry's son Scythrop is recovering from a love affair which ended badly. A failed author, he often retires to his own quarters in a tower to study. When he leaves them, he is distracted by the flirtatious Marionetta, who blows hot and cold on his affections. A further complication arises when Celinda Toobad, fleeing from a forced engagement to an unknown suitor, appeals to Scythrop for shelter and he hides her in a secret room. The change in Scythrop's demeanour spurs on Marionetta to threaten to leave him forever, and he is forced to admit to himself that he is in love with both women and cannot choose between them.

There is a brief interruption to the usual round of life at the Abbey when the misanthropic poet, Mr Cypress, pays a farewell visit before going into exile. After his departure, there are reports of a ghost stalking the building, and the appearance of a ghastly figure in the library throws the guests into consternation. Only later is the apparition revealed to have been Mr Glowry's somnambulant steward Crow.

Scythrop's secret comes out when Mr Glowry confronts his son in his tower and asks what are his intentions towards Marionetta, "whom you profess to love". Hearing this, Miss Toobad (who has been passing herself off under the name of Stella) comes out of the hidden chamber and demands an explanation. During the ensuing row, Mr Toobad recognises his runaway daughter, whom he had really intended for Scythrop all along. But both women now renounce Scythrop and leave the Abbey, determined never to set eyes on him again.

After all the guests depart, Scythrop proposes suicide and asks his servant Raven to bring him "a pint of port and a pistol". He is only dissuaded when his father promises to leave for London and intercede for his forgiveness with one or other of the women. When Mr Glowry returns, it is with letters from Celinda and Marionetta, who announce their forthcoming marriage to two of the other guests instead. Scythrop is left to console himself with the thought that his recent experiences qualify him "to take a very advanced degree in misanthropy" so that he may yet hope to make a figure in the world.

Characters

[edit]

Many of the characters who figure in the novel are based on real people. The names they are given by Peacock express their personality or governing interest.

The family

[edit]- Christopher Glowry, Esquire

- The melancholy master of Nightmare Abbey. That property is modelled on the gothic styled Albion House in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, rented by the Shelleys in 1816–17 and not far from which Peacock wrote his novel.[7] Mr Glowry is apparently a purely fictional character whose name derives from 'glower', a synonym of frown or scowl.

- Scythrop

- Mr Glowry's only son, named after an ancestor who hanged himself. The name is derived from the Greek σκυθρωπος (skythrōpos, "of sad or gloomy countenance"). It is generally accepted that Scythrop shares many traits with Peacock's friend Percy Bysshe Shelley. Scythrop, like Shelley, for example, would much prefer to enjoy two mistresses than choose between them, and some critics have noticed that in both of Shelley's gothic novellas, Zastrozzi (1810) and St Irvyne (1811), the hero is loved by two women at the same time.[8] Scythrop’s unlucky affairs of the heart also have similar endings. Prior to the novel’s start, his match with Emily Girouette had been called off. Though they had parted "vowing everlasting constancy", she had married someone else within three weeks. Girouette is the French for "weathercock" and the episode was based on Shelley's romance with his cousin Harriet Grove (1791–1867).[9] Nor was Scythrop any luckier with his two other loves, both of whom married within a month of leaving the Abbey.

- Miss Marionetta Celestina O'Carroll

- The first of Scythrop's later loves, she was the orphaned daughter of Mr Glowry's youngest sister, who had formerly made a runaway love-match with an Irish officer O'Carroll. When her mother died, Marionetta was taken in by Mr Glowry's other sister, Mrs Hilary. A capricious coquette, she is generally identified with Harriet Westbrook, a schoolmate of Shelley's sister Hellen, with whom Shelley eloped when she was 16.[10]

- Mr Hilary

- Scythrop's uncle, the husband of Mr Glowry's elder sister. His name is derived from the Latin hilaris, "cheerful", and his declared belief is that "the highest wisdom and the highest genius have been invariably accompanied by cheerfulness". It is only family business that takes him to Nightmare Abbey.

The visitors

[edit]- Mr Toobad

- A Manichaean Millenarian – that is to say, he is a Manichaean in that he believes that the world is governed by two powers, one good and one evil; and he is a Millenarian in that he believes that the evil power is currently in the ascendant but will eventually be succeeded by the good power – "though not in our time". His favourite quotation is Revelation 12:12: "Woe to the inhabiters of the earth and of the sea! for the devil is come among you, having great wrath, because he knoweth that he hath but a short time". His character is based on J. F. Newton, a member of Shelley's circle.[11]

- Miss Celinda Toobad

- Daughter of the above and the second lady involved in Scythrop's love triangle. Her intellectual and philosophical qualities are contrasted with the more conventional femininity of Marionetta. She adopts the pseudonym Stella, the name of the eponymous heroine of a drama by Goethe who is involved in a similar love-triangle. There is some uncertainty about the identity of Celinda's historical counterpart. It is often said that she is based upon Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin.[12] But Celinda's appearance is quite different from that of the future Mary Shelley, and this has led some commentators to surmise that the person Peacock had in mind when he created Celinda/Stella was in fact Shelley's soul mate Elizabeth Hitchener[13] or Claire Clairmont.[14] Of a gloomy disposition and educated in a German convent, she was one of the only seven readers of Scythrop's treatise Philosophical Gas; or, a Project for a General Illumination of the Human Mind.

- Mr Ferdinando Flosky

- "A very lachrymose and morbid gentleman of some note in the literary world". His name is identified in a footnote by Peacock as a corruption of Filosky, from the Greek φιλοσκιος (philoskios, a lover of shadows). Mr Flosky is a satirical portrait of the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge,[15] most of whose conversation is unintelligible – and meant to be so. His criticisms of contemporary literature echo remarks made by Coleridge in his Biographia Literaria; his ability to compose verses in his sleep is a playful reference to Coleridge's account of the composition of Kubla Khan; and his claim to have written the best parts of his friends' books also echoes a similar claim made by Coleridge. Both men are deeply influenced by German philosophy, especially the transcendental idealism of Immanuel Kant. Throughout the novella there are many minor allusions that confirm the Flosky–Coleridge identification.[16]

- The Honourable Mr Listless

- A fashionable, former fellow-collegian of Scythrop, for whom the making of any effort is a challenge. He is based on Lumley Skeffington, a friend of Shelley's.[17] His drunken French valet Fatout is constantly called on to function as his master's memory. This behaviour is founded on the Windermere anecdote[18] related of Beau Brummel.[19]

- Mr Cypress

- A misanthropic poet who is about to go into exile. He too was a college friend of Scythrop and is a great favourite of Mr Glowry's. Based on Lord Byron,[20] he dominates the single chapter in which he appears, where most of the poet's conversation is made up of phrases borrowed from the fourth canto of Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. This was a particular target of Peacock, on which he had commented, "I think it necessary to 'make a stand' against 'encroachments' of black bile. The fourth canto is really too bad. I cannot consent to be auditor tantum of this systematical 'poisoning' of the 'mind' of the 'reading public'."[21] The choice of name for the character, deriving from the Greek like those of others in the novel, is governed by the tree's association with graveyards.[22]

- Mr Asterias

- An ichthyologist and amateur scientist, his name is that of the genus to which starfish belong. The character caricatures Sir John Sinclair.[23]

- Reverend Mr Larynx

- The vicar of nearby Claydyke, who readily adapts himself to whatever company he is in.

References

[edit]- ^ Butler, Marilyn (1979). "The Critique of Romanticism: Nightmare Abbey". Peacock Displayed: A Satirist in His Context. Routledge & K. Paul. p. 102. ISBN 978-0710002938. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ Kiernan, Robert F. (1990). Frivolity Unbound: Six Masters of the Camp Novel. Continuum Publishing. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0826404657. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Peacock", Temple Bar, Volume 80 (May–August 1887), p. 48

- ^ Bryan Burns, The Novels of Thomas Love Peacock, Rowman & Littlefield, 1985, p.76

- ^ Theatricalia

- ^ Gin & Co., London

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 149

- ^ Aurélien A. Digeon, "Shelley and Peacock", Modern Language Notes 25.2 (Feb., 1910), pp. 41-45

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 468

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 823

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 705

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 823

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 510

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 299

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 311

- ^ David M. Baulch, "The 'Perpetual Exercise of an Interminable Quest': The 'Biographia Literaria' and the Kantian Revolution, Studies in Romanticism 43.4 (Winter 2004), pp. 557–81

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 834

- ^ John Timbs, A Century of Anecdote from 1760 to 1860, London 1873, p.88

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 241

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 259

- ^ Mills, Howard W. (1976). "Nightmare Abbey (1968)". In Sage, Lorna (ed.). Peacock: The Satirical Novels: A Casebook. Macmillan. p. 200. ISBN 978-0333184103. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ Mrs. Samuel Greg, Walter in the Woods: or Trees and Common Objects of the Forest Described and Illustrated, London 1870, p. 109

- ^ Rintoul 1993, p. 831

Bibliography

[edit]- Claude Annett Prance, The Characters in the Novels of Thomas Love Peacock, E. Mellen Press, 1992

- M. C. Rintoul, Dictionary of Real People and Places in Fiction, Routledge 1993

External links

[edit]- Nightmare Abbey at Standard Ebooks

- Nightmare Abbey at Project Gutenberg

- Nightmare Abbey at The Thomas Love Peacock Society

Nightmare Abbey public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Nightmare Abbey public domain audiobook at LibriVox

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch