Olive wreath

The olive wreath, also known as kotinos (Greek: κότινος),[1] was the prize for the winner at the ancient Olympic Games. It was a branch of the wild olive tree[2] Kallistefanos Elea[3] (also referred to as Elaia Kallistephanos)[4] that grew at Olympia,[5] intertwined to form a circle or a horse-shoe. The branches of the sacred wild-olive tree near the temple of Zeus were cut by a pais amphithales (Ancient Greek: παῖς ἀμφιθαλής, a boy whose parents were both alive) with a pair of golden scissors. Then he took them to the temple of Hera and placed them on a gold-ivory table. From there, the Hellanodikai (the judges of the Olympic Games) would take them, make the wreaths and crown the winners of the Games.[6]

History

[edit]

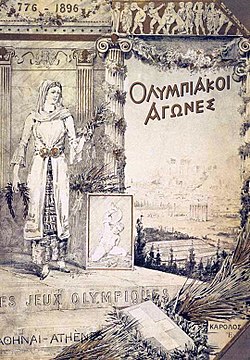

According to Pausanias it was introduced by Heracles as a prize for the running race winner to honor his father Zeus.[7] In the ancient Olympic Games there were no gold, silver, or bronze medals. There was only one winner per event, crowned with an olive wreath made of wild-olive leaves from a sacred tree near the temple of Zeus at Olympia. Olive wreaths were part of the iconography of the founding of the modern Olympic games, with imagery that has the wreath connecting the ancient practice and dates with the events in 1896.[8] Olive wreaths were given out during the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens in honor of the ancient tradition, because the games were being held in Greece which was also used as the official emblem.[9]

Herodotus describes the following story which is relevant to the olive wreath. Xerxes was interrogating some Arcadians after the Battle of Thermopylae. He inquired why there were so few Greek men defending the Thermopylae. The answer was "All other men are participating in the Olympic Games". And when asked "What is the prize for the winner?", "An olive-wreath" came the answer. Then Tiritantaechmes, one of his generals uttered: "Good heavens! Mardonius, what kind of men are these against whom you have brought us to fight? Men who do not compete for possessions, but for virtue."'[10]

Aristophanes in Plutus makes a humorous comment on victorious athletes who are crowned with wreath made of wild olive instead of gold:[11]

Why, Zeus is poor, and I will clearly prove it to you. In the Olympic games, which he founded, and to which he convokes the whole of Greece every four years, why does he only crown the victorious athletes with wild olive? If he were rich he would give them gold.

The victorious athletes were honoured, feted, and praised. Their deeds were heralded and chronicled so that future generations could appreciate their accomplishments. In fact, the names of the Olympic winners formed the chronology basis of the ancient world, as arranged by Timaeus in his work, The Histories.

Amongst the many cultural references concerning the olive wreath, the first line of the first stanza in the Mexican national anthem calls for the motherland, figuratively, to keep hold of the olive wreath surrounding "its temples", a wreath which was given by a holy archangel, for God himself has already written this motherland's destiny.

See also

[edit]- Olympic medal

- Ancient Olympic Games

- Olive branch

- Laurel wreath

- Klila, myrtle wreath in Mandaeism

- Wreaths and crowns in antiquity

References

[edit]- ^ LSJ entry κότινος

- ^ "As a result of the early domestication and extensive cultivation of the olive tree throughout the Mediterranean Basin, the wild-looking forms of olive (oleasters) presently observed constitute a complex, potentially ranging from wild to feral forms." observe R Lumaret, N Ouazzani, H Michaud, G Vivier, "Allozyme variation of oleaster populations (wild olive tree)(Olea europaea L.) in the Mediterranean Basin" Heredity, 2004; feral "wild" olives (Olea europaea) were distinguished by Theophrastus and other ancient Greeks from kotinos the wild-olive, today informally but confusingly rendered oleaster; compare the unrelated modern genus Cotinus, from Anc. Gr. kotinos.

- ^ The Olympic Games- Retrieved 2018-07-02

- ^ Garden Collage- Retrieved 2018-07-02

- ^ Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants, IV.13.2: 'the wild-olive [kotinos] at Olympia, from which the wreaths for the games are made".

- ^ "Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού – Αφιερώματα". odysseus.culture.gr.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 5.7.7

- ^ Kyle, Donald G. (2015). Sport and spectacle in the ancient world (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-118-61380-1. OCLC 886673192.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Carruthers, Emile (2017-05-04). "The Ancient Origins of the Flower Crown". The Iris. The Getty. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, Hdt. 8.26

- ^ Aristophanes, Plutus, 585.

External links

[edit]- What prizes did Olympic victors get? at Perseus

- Winners' rewards in Antiquity not in numbness (page 11)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch