Trial by ordeal

Trial by ordeal was an ancient judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused (called a "proband"[1]) was determined by subjecting them to a painful, or at least an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience. In medieval Europe, like trial by combat, trial by ordeal, such as cruentation, was sometimes considered a "judgement of God" (Latin: jūdicium Deī, Old English: Godes dōm): a procedure based on the premise that God would help the innocent by performing a miracle on their behalf. The practice has much earlier roots, attested to as far back as the Code of Hammurabi and the Code of Ur-Nammu.

In pre-industrial society, the ordeal typically ranked along with the oath and witness accounts as the central means by which to reach a judicial verdict. Indeed, the term ordeal, Old English ordǣl, has the meaning of "judgment, verdict" from Proto-West Germanic uʀdailī (see German: Urteil, Dutch: oordeel), ultimately from Proto-Germanic *uzdailiją "that which is dealt out".

Priestly cooperation in trials by fire and water was forbidden by Pope Innocent III at the Fourth Council of the Lateran of 1215 and replaced by compurgation. Trials by ordeal became rarer over the Late Middle Ages, but the practice was not discontinued until the 16th century. Certain trials by ordeal would continue to be used into the 17th century in witch-hunts.[2]

Types of ordeals

[edit]By combat

[edit]Ordeal by combat took place between two parties in a dispute, either two individuals, or between an individual and a government or other organization. They, or, under certain conditions, a designated "champion" acting on their behalf, would fight, and the loser of the fight or the party represented by the losing champion was deemed guilty or liable. Champions could be used by one or both parties in an individual versus individual dispute, and could represent the individual in a trial by an organization; an organization or state government by its nature had to be represented by a single combatant selected as champion, although there are numerous cases of high-ranking nobility, state officials and even monarchs volunteering to serve as champion. Combat between groups of representatives was less common but still occurred.

A notable case was that of Gero, Count of Alsleben, whose daughter married Siegfried II, Count of Stade.

By fire

[edit]

Ordeal by fire was one form of torture. The ordeal by fire has been recorded as having been conducted throughout Europe, as well as in Eastern societies, such as ancient India and Iran. In Europe, the ordeal typically required that the accused walk a certain distance, usually 9 feet (2.7 metres) or a certain number of paces, usually three, over red-hot plowshares or holding a red-hot iron. Innocence was sometimes established by a complete lack of injury, but it was more common for the wound to be bandaged and re-examined three days later by a priest. It would either be pronounced that God had intervened to heal the wound, or that it was festering, in which case the suspect would be exiled or put to death. Ordeal by fire could also include methods where the accused was made to pass through flames, with evidence of such methods being mainly found outside Western Europe.

In Europe

[edit]One famous story about the ordeal of plowshares concerns the English King Edward the Confessor's mother, Emma of Normandy. According to a legend, she was accused of adultery with Bishop Ælfwine of Winchester but proved her innocence by walking barefoot unharmed over red-hot plowshares.

During the First Crusade, the French mystic Peter Bartholomew allegedly went through the ordeal by fire in 1099 by his own choice to disprove a charge that his claimed discovery of the Holy Lance was fraudulent. He died as a result of his injuries.[3]

Trial by ordeal was adopted in the 13th century by the Byzantine successor states the Empire of Nicaea and the Despotate of Epirus; Michael Angold speculates this legal innovation was most likely through "the numerous western mercenaries in Byzantine service both before and after 1204."[4] It was used to prove the innocence of the accused in cases of treason and use of magic to affect the health of the emperor. The most famous case where this was employed was when Michael Palaiologos was accused of treason: he avoided enduring the red-iron by saying he would only hold it if the Metropolitan Phokas of Philadelphia could take the iron from the altar with his own hands and hand it to him.[5] However, the Byzantines viewed trial by ordeal with disgust and considered it a barbarian innovation at odds with Byzantine law and ecclesiastical canons. Angold notes, "Its abolition by Michael Palaiologos was universally acclaimed."[6]

In 1498, Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, the leader of a reform movement in Florence who claimed apocalyptic prophetic visions, attempted to prove the divine sanction of his mission by undergoing a trial by fire. The first of its kind in over 400 years, the trial was a fiasco for Savonarola, since a sudden rain doused the flames, canceling the event and taken by onlookers as a sign from God against him. The Inquisition arrested him shortly thereafter, with Savonarola convicted of heresy and hanged at the Piazza della Signoria in Florence.

In Persia

[edit]Ordeal by fire (Persian: ور) was also used for judiciary purposes in ancient Iran. Persons accused of cheating in contracts or lying might be asked to prove their innocence by ordeal of fire as an ultimate test. Two examples of such an ordeal include the accused having to pass through fire, or having molten metal poured on their chest. There were about 30 of these kinds of fiery tests in all. If the accused died, they were held to have been guilty; if survived, they were innocent, having been protected by Mithra and the other gods. The most simple form of such ordeals required the accused to take an oath, then drink a potion of sulfur (Avestan: saokant, lit. 'sulfur', Middle Persian: sōgand, lit. 'oath', Persian: سوگند, romanized: sowgand, lit. 'oath'). It was believed that fire had an association with truth and hence with asha.[7]

In India

[edit]In ancient India, the trial by fire was known as agnipariksha, in which Agni, the Fire God, would be invoked by a priest using mantras. After the invocation, a pyre would be built and lit, and the accused would be asked to sit on it. According to Hindu mythology, the Fire God would preserve the accused if they were innocent, if not, they would be burned to ashes.[8][9]

In Cambodia

[edit]In 13th-century Angkor, according to a book written by a visiting Chinese official, trial by ordeal was a common solution to disputes. Members of two feuding families were ordered to sit in separate stone pagodas for up to four days, and it was believed that only the family in the wrong would get sick. Suspected thieves were tried by boiling oil. [10]

By boiling oil

[edit]Trial by boiling oil has also been practiced in villages in certain parts of West Africa, such as Togo.[11] There are two primary versions of this trial. In one, the accused parties are ordered to retrieve an item from a container of boiling oil, with those who refuse the task being found guilty.[12] In the other, both the accused and the accuser have to retrieve an item from boiling oil, with the person or persons whose hand remains unscathed being declared innocent.[11]

By water

[edit]There were different types of trials by water: trial by hot water and trial by cold water.

Hot water including trial by combat

[edit]First mentioned in the 6th-century Salic law, the ordeal of hot water required the accused to dip their hand into a kettle or pot of boiling water (sometimes oil or lead was used instead) and retrieve a stone. Assessment of the injury was similar to that of the fire ordeal. An early (non-judicial) example of the test was described by Bishop Gregory of Tours in the late 6th century. He describes how a Catholic saint, Hyacinth,[clarification needed] bested an Arian rival by plucking a stone from a boiling cauldron. Gregory said that it took Hyacinth about an hour to complete the task (because the waters were bubbling so ferociously), but he was pleased to record that when the heretic tried, he had the skin boiled off up to his elbow.[citation needed]

Legal texts from the reign of King Athelstan (Lived: c. 894 – 27 October 939, Ruled: 924 – 939) provide some of the most elaborate royal regulations for the use of the ordeal in Anglo-Saxon England, though the period's fullest account of ordeal practices is found in an anonymous legal text written sometime in the 10th century.[13] According to this text, usually given the title Ordal, the water had to be close to boiling temperature, and the depth from which the stone had to be retrieved was up to the wrist for a 'one-fold' ordeal and up to the elbow for a 'three-fold' ordeal.[14] The distinction between the one-fold and three-fold ordeal appears to be based on the severity of the crime, with the threefold ordeal being prescribed for more severe offences such as treachery or for notorious criminals.[15] The ordeal would take place in a church, with several in attendance, purified and praying to God to reveal the truth. Afterwards, the hand was bound and examined after three days to see whether it was healing or festering.[16]

This was still an isolated practice in remote 12th-century Catholic churches. A suspect would place their hand in the boiling water. If after three days God had not healed their wounds, the suspect was guilty of the crime.[17]

Cold water

[edit]The ordeal of cold water has a precedent in the 13th law of the Code of Ur-Nammu[18] (the oldest known surviving code of laws) and the second law of the Code of Hammurabi.[19] Under the Code of Ur-Nammu, a man who was accused of what some scholars have translated as "sorcery" was to undergo ordeal by water. If the man were proven innocent through this ordeal, the accuser was obligated to pay three shekels to the man who underwent judgment.[18] The Code of Hammurabi dictated that, if a man was accused of a matter by another, the accused was to leap into a river. If the accused man survived this ordeal, the accused was to be acquitted. If the accused was found innocent by this ordeal, the accuser was to be put to death and the accused man was to take possession of the then-deceased accuser's house.[19] The Code of Hammurabi also stated that if a woman is accused of adultery she "will leap into the river-god for her husband." However, it is unclear if innocence is proved by drowning or surviving.[20]

An ordeal by cold water is mentioned in the Vishnu Smrti,[21] which is one of the texts of the Dharmaśāstra.[21]

The practice was also set out in Salic law but was abolished by Emperor Louis the Pious in 829. The practice reappeared in the Late Middle Ages: in the Dreieicher Wildbann of 1338, a man accused of poaching was to be submerged in a barrel three times and to be considered innocent if he sank, and guilty if he floated.

Witch-hunts in Europe

[edit]Ordeal by water was associated with the witch-hunts of the 16th and 17th centuries, although an inverse of most trials by ordeal; if the accused sank, they were considered innocent, whereas if they floated, this indicated witchcraft. The ordeal would be conducted with a rope holding the subject so that the person being tested could be retrieved following the trial. A witch trial including this ordeal took place in Szeged, Hungary as late as 1728.[22]

Demonologists varied in their explanations as to why trial by water would be effective, although spiritual explanations were most common. Some argued that witches floated because they had renounced baptism when entering the Devil's service. King James VI of Scotland claimed in his Daemonologie that water was so pure an element that it repelled the guilty. Jacob Rickius claimed that witches were supernaturally light and recommended weighing them as an alternative to dunking them; this procedure and its status as an alternative to dunking were parodied in the 1975 British film Monty Python and the Holy Grail.[23]

By cross

[edit]The ordeal of the cross was apparently introduced in the Early Middle Ages in an attempt to discourage judicial duels among Germanic peoples. As with judicial duels, and unlike most other ordeals, the accuser had to undergo the ordeal together with the accused. They stood on either side of a cross and stretched out their hands horizontally. The first one to lower their arms lost. This ordeal was prescribed by Charlemagne in 779 and again in 806. A capitulary of Louis the Pious in 819[24] and a decree of Lothar I, recorded in 876, abolished the ordeal so as to avoid the mockery of Christ.

By ingestion

[edit]Franconian law prescribed that an accused was to be given dry bread and cheese blessed by a priest. If the accused choked on the food, they were considered guilty. This was transformed into the ordeal of the Eucharist (trial by sacrament) mentioned by Regino of Prüm ca. 900:AD; the accused was to take the oath of innocence. It was believed that if the oath had been false, the person would die within the same year.

Numbers 5:12–27 prescribes that a woman suspected of adultery should be made to swallow "the bitter water that causeth the curse" by the priest in order to determine her guilt. The accused would be condemned only if 'her belly shall swell and her thigh shall rot'. One writer has recently argued that the procedure has a rational basis, envisioning punishment only upon clear proof of pregnancy (a swelling belly) or venereal disease (a rotting thigh). Other scholars think an abortifacient a more likely explanation; if the holy water causes miscarriage, it is proof of guilt).[25] The descriptor “bitter” in the original Hebrew is written as “mārîm” which can also be understood as “poison”. However, it is unclear if the water actually contains any actual poison.[26]

Some cultures, such as the Efik Uburutu people of present-day Nigeria, would administer the poisonous Calabar bean (Physostigma venenosum, known as esere in Efik), which contains physostigmine, in an attempt to detect guilt. A defendant who vomited up the bean was innocent. A defendant who became ill or died was considered guilty.[27][28]

Residents of Madagascar could accuse one another of various crimes, including theft, Christianity, and especially witchcraft, for which the ordeal of tangena (Cerbera manghas) was routinely obligatory. In the 1820s, ingestion of the poisonous nut caused about 1000 deaths annually. This average rose to around 3000 annual deaths between 1828 and 1861.[29]

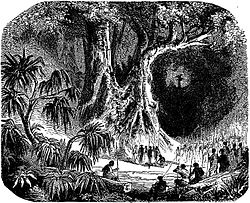

Ancient Liberian cultures practiced a tradition known as sassywood.[30] In it, a poisonous brew of erythrophleine, extracted from the bark of the "Ordeal Tree" (erythrophleum suaveolens), was administered to the defendant. While it has largely been outlawed, the practice is still in sporadic use by local communities.[31]

In Africa Cassaine has been, and is still, used as an ordeal poison.

The "penalty of the peach" was an ancient ordeal that involved peach pits or their extracts. The pits contain amygdalin, which is metabolized into cyanide.[28]

In early modern Europe, the Mass was used as a form of ordeal by ingestion: a suspected party was forced to take the Eucharist because they would be eternally damned if they were guilty, and thus their unwillingness to take the test would give an indication of their guilt.[32]

By turf

[edit]An Icelandic ordeal tradition involves the accused walking under a piece of turf. If the turf falls on the accused's head, the accused person is pronounced guilty.[33]

The ordeal of bleeding (Bier-Right) (Cruentation)

[edit]This ordeal took place when there was a murder. The person who was charged with the murder is to approach the dead body from the murder. If the corpse starts to bleed then the case is proven.[34] in other cases the wounds of the victim would start to bleed[35] “...the blood cry as a divinely revealed piece of legal evidence, extracted through irrepressible force and expressed through the active demonstration of the corpse ‘bleeding afresh.’”[36]

English common law

[edit]The ordeals of fire and water in England likely have their origin in Frankish tradition, as the earliest mention of the ordeal of the cauldron is in the first recension of the Salic Law in 510.[37] Trial by cauldron was an ancient Frankish custom used against both freedmen and slaves in cases of theft, false witness and contempt of court, where the accused was made to plunge their right hand into a boiling cauldron and pull out a ring.[38] As Frankish influence spread throughout Europe, ordeal by cauldron spread to neighboring societies.[39]

The earliest references of ordeal by cauldron in the British Isles occurs in Irish law in the seventh century, but it is unlikely that this tradition shares roots with the Frankish tradition that is likely the source of trial by fire and water among the Anglo-Saxons and later the Normans in England.[40] The laws of Ine, King of the West Saxons, produced around 690, contains the earliest reference to ordeal in Anglo-Saxon law; however, this is the last and only mention of ordeal in Anglo-Saxon England until the 10th century.[41]

After the Conquest of 1066, the Old English customs of proof were repeated anew and in more detailed fashion by the Normans, but the only notable innovation of the ordeal by the conquerors was the introduction of the trial by battle.[42] There were, however, minor conflicts between the customs of the Anglo-Saxons and the customs of the Normans that were typically resolved in ways that favored the Normans.[43] In a famous story from Eadmer's Historia novorum in Anglia, William Rufus expresses skepticism about the ordeal after 50 men accused of forest offenses were exonerated by the ordeal of hot iron. In this story, Rufus states that he will take judgment from God's hands into his own.[44] However, this skepticism was not universally shared by the intellectuals of the day, and Eadmer depicts Rufus as irreligious for rejecting the legitimacy of the ordeal.[45]

The use of the ordeal in medieval England was very sensitive to status and reputation in the community. The laws of Canute distinguish between "men of good repute" who were able to clear themselves by their own oath, "untrustworthy men" who required compurgators, and untrustworthy men who cannot find compurgators who must go to the ordeal. One of the laws of Ethelred the Unready declared that untrustworthy men were to be sent to the triple ordeal, that is, an ordeal of hot iron where the iron is three times heavier than that used in the simple ordeal, unless his lord and two other knights swear that he has not been accused of a crime recently, in which case he would be sent to an ordinary ordeal of hot iron.[46]

Unlike other European societies, the English rarely employed the ordeal in non-criminal proceedings.[47] The mandatory use of the ordeal in certain criminal proceedings appears to date from the Assize of Clarendon in 1166.[48] Prior to then, compurgation was the most usual method of proof, and the ordeal was used in cases where there was some presumption of guilt against the accused or when the accused was bound to fail in compurgation.[49] A distinction was made between those accused fama publica (by public outcry) and those accused on the basis of specific facts. Those accused fama publica were able to exculpate themselves by means of compurgation, whereas those accused on the basis of specific facts and those who were thought to have bad character were made to undergo the ordeal.[50]

The Assize of Clarendon declared that all those said by a jury of presentment to be "accused or notoriously suspect" of robbery, thievery, or murder or of receiving anyone who had committed such a wrong were to be put to the ordeal of water.[48] These juries of presentment were the hundred juries and vills, and these groups, in effect, made the intermediate decision of whether an accused person would face the more final judgment of the ordeal. These bodies rendered "verdicts" of either suspected or not suspected. In cases where the defendant was accused on the basis of one or more specific facts, the defendant was sent to the ordeal upon the verdict of the hundred jury alone. In cases where the defendant was accused fama publica, the agreement of the hundred jurors and the vills as to the defendant's suspicion was required to send him to the ordeal.[50] However, the intermediate accusation of the juries could still be considered final in some sense as any person who was accused of murder by the juries was required to leave the realm even if he was exonerated by the ordeal.[51]

In 1215, clergy were forbidden to participate in ordeals by the Fourth Lateran Council. The English plea rolls contain no cases of trial by ordeal after 1219, when Henry III recognized its abolition.[52]

Suppression

[edit]Popes were generally opposed to ordeals, although there are some apocryphal accounts describing their cooperation with the practice.[2] At first there was no general decree against ordeals, and they were only declared unlawful in individual cases.[2] Eventually Pope Innocent III in Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) promulgated a canon forbidding blessing of participants before ordeals.[2] This decision was followed by further prohibitions by synods in thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[2] The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1194–1250) was the first king who explicitly outlawed trials by ordeal as they were considered irrational (Constitutions of Melfi).[53] In England, things started to change with King Henry III (1220).

From the twelfth century, the ordeals started to be generally disapproved and they were discontinued during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Although papal authority had stood against ordeals generally since Innocent III, the interplay of canon and common law was such that a clear anathema on the practice given in 1215 would have unintended consequences and overstepped the bounds of ecclesiastical authority. Secular authorities might deem someone guilty if they relied on clerical authority to avoid an ordeal, and certain "occult" crimes (those to which there would not normally be witnesses) could not be effectively prosecuted in the legal system of the time by any other means than ordeal. Innocent III's prohibition of clerical participation in trial by ordeal was essentially a call to action for secular authorities to move away from it, a process which took centuries to complete.[54]

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries some kinds of ordeals were once again used in witch-hunts, although these were actually intended more as a physical test of whether the accused would float, rather than an ordeal invoking divine intervention to prove or disprove guilt, i.e., a witch floated by the nature of a witch, not because God intervened and caused her to float, demonstrating her guilt.[2]

Modern theories

[edit]According to a theory put forward by economics professor Peter Leeson, trial by ordeal may have been effective at sorting the guilty from the innocent.[55] On the assumption that defendants were believers in divine intervention for the innocent, then only the truly innocent would choose to endure a trial; guilty defendants would confess or settle cases instead. Therefore, the theory goes, church and judicial authorities could routinely rig ordeals so that the participants—presumably innocent—could pass them.[56] To support this theory, Leeson points to the great latitude given to the priests in administering the ordeal and interpreting the results of the ordeal. He also points to the overall high exoneration rate of accused persons undergoing the ordeal, when intuitively one would expect a very high proportion of people carrying a red hot iron to be badly burned and thus fail the ordeal.[55] Peter Brown explains the persistence and eventual withering of the ordeal by stating that it helped promote consensus in a society where people lived in close quarters and there was little centralized power. In a world where "the sacred penetrated into the chinks of the profane and vice-versa" the ordeal was a "controlled miracle" that served as a point of consensus when one of the greatest dangers to the community was feud.[57] From this analysis, Brown argues that the increasing authoritativeness of the state lessened the need and desire for the ordeal as an instrument of consensus, which ultimately led to its disappearance.[58]

See also

[edit]- Baptism by fire

- Bisha'a – trial by ordeal among the Bedouin

- Ecclesiastical court

- Trial by combat

- Trial by jury

References

[edit]- ^ Kerr, Margaret H.; Forsyth, Richard D.; Plyley, Michael J. (1992). "Cold Water and Hot Iron: Trial by Ordeal in England". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 22 (4): 573–595. doi:10.2307/205237. ISSN 0022-1953. JSTOR 205237.

- ^ a b c d e f Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades: Volume 1, The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980), p. 274

- ^ Angold, A Byzantine Government in Exile: Government and Society Under the Laskarids of Nicaea (1204–1261), (Oxford: University Press, 1975), p. 172

- ^ Denno J. Geanakoplos, Emperor Michael Palaeologus and the West (Harvard University Press, 1959), pp. 23f

- ^ Angold, Byzantine Government, p. 174

- ^ Boyce, Mary (2001). "Ātaš". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 3. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Sita proves her purity by fire ordeal (Thai Ramayana mural)". NCpedia.

- ^ Kinsley, David R. (1986) [1997]. Hindu goddesses : visions of the divine feminine in the Hindu religious tradition; with new preface. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06339-6. OCLC 772861669.

- ^ (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b "Justice". Taboo. Season 2. Episode 1. 6 October 2003. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Men undergo trial by boiling water over stolen food". The Irish Independent. Dublin. 19 September 2006. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011.

- ^ Patrick Wormald, The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, Vol I: Legislation and its Limits (Oxford, 1999), pp. 373–74

- ^ F. Liebermann, Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen vol. I: Text und Übersetzung (Halle, 1903), p. 386

- ^ Patrick Wormald, Papers Preparatory to the Making of English Law, vol. II: From God's Law to Common Law, ed. Stephen Baxter and John Hudson (2014), pp. 78–79 at "Early English Laws: Patrick Wormald, Papers Preparatory to the Making of English Law, vol. II". Archived from the original on 2014-10-01. Retrieved 2014-10-01.. See for example, II As 4, 5, 6.1, I Atr 1.1, III Atr 3.4, V Atr 30, VI Atr 37, II Cn 30 all in Liebermann, Gesetze vol 1.

- ^ Halsall, Paul, ed. (21 June 1998). "The Laws of King Athelstan 924-939 A.D." Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Halsall, Paul, ed. (January 1996). "Ordeal of Boiling Water, 12th or 13th Century". Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ a b S. N. Kramer. (1954). "Ur-Nammu Law Code". Orientalia, 23 (1), 40

- ^ a b King, L. W., The Code of Hammurabi, Yale Law School: The Avalon Project (Lillian Goldman Law Library, 2008), retrieved May 5, 2021 from https://avalon.law.yale.edu/ancient/hamframe.asp

- ^ McKane, W. (October 1980). "Poison, Trial by Ordeal and the Cup of Wrath". Vetus Testamentum. 30 (4): 474–492. doi:10.2307/1517857. JSTOR 1517857.

- ^ a b Jolly, Julius, trans. (1880). "XII". In Müller, F. Max (ed.). Sacred Books of the East. Vol. 7. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2006-10-17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Böhmer, Justus Henning (1744). Jus ecclesiasticum protestantium (in Latin). Halle-Magdeburg: Impensis Orphanotrophei. OL 17577078M.

- ^ Lea, Henry C. (1866). Superstition and Force. Philadelphia: Collins, Printer. OCLC 18128359.

- ^ Boretius, Alfredus [in German], ed. (1883). "VII. Hludowici Pii Capitularia 814–37". Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Capitularia regum Francorum I (in Latin). Hannover: Societas Aperiendis Fontibus Rerum Germa. p. 279.

- ^ Kadri, Sadakat (2005). The Trial: A History from Socrates to O.J. Simpson. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780375505508. OCLC 624723889.

- ^ Mckane, W. (1980-01-01). "Poison, Trial By Ordeal and the Cup of Wrath". Vetus Testamentum. 30 (4): 474–492. doi:10.1163/156853380X00434. ISSN 0042-4935.

- ^ Delaterre, Flora. "Calabar Bean". Flora Delaterre -Plant Information. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ a b Nelson, Lewis S.; Hoffman, Robert S.; Howland, Mary Ann; Lewin, Neal A.; Goldfrank, Lewis R. (2018). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies, Eleventh Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 9781259859595.

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (October 1991). "The state and pre-colonial demographic history: the case of nineteenth century Madagascar". Journal of African History. 23 (3): 415–45. doi:10.1017/S0021853700031534. JSTOR 182662.

- ^ Leeson, P. T.; Coyne, C. J. (2012). "Sassywood" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Economics. 40 (4): 608. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2012.02.002.

- ^ "Trial by ordeal makes the guilty burn but "undermines justice"". IRIN. 1 November 2007.

- ^ Thomas, Keith (2012) [1st pub. 1971]. Religion and the Decline of Magic. London: Folio Society. p. 42. OCLC 805007047.

- ^ Miller, William Ian (1988). "Ordeal in Iceland". Scandinavian Studies. 60 (2): 189–218. JSTOR 40918943.

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles; Howland, Arthur E. (1973). The Ordeal. University of Pennsylvania Press. JSTOR j.ctt1ffjntb.

- ^ Cross, Cameron M (2021-10-30). "Cloak and Cruentation: Power, (In)Visibility and the Supernatural in the 'Nibelungenlied'". Reinvention: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research. 14 (2). doi:10.31273/reinvention.v14i2.714. ISSN 1755-7429.

- ^ Rosen, Rebecca M. (2022). ""The Voice of the Innocent Blood Cries Aloud from the Ground to Heaven": Speaking and Discovering Infanticide in the Early American Northeast". Early American Literature. 57 (1): 85–122. ISSN 0012-8163. JSTOR 27113016.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 4–7.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 4, 9.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 9.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 5.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 7.

- ^ Paul Hyams (1981). Arnold, Morris S. (ed.). On the Laws and Customs of England. Essays in Honor of Samuel E. Thorne. University of North Carolina Press. p. 111.

- ^ Paul Hyams (1981). Arnold, Morris S. (ed.). On the Laws and Customs of England. Essays in Honor of Samuel E. Thorne. University of North Carolina Press. p. 112.

- ^ Paul Hyams (1981). Arnold, Morris S. (ed.). On the Laws and Customs of England. Essays in Honor of Samuel E. Thorne. University of North Carolina Press. p. 116.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 76.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 31.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 63.

- ^ a b Kerr, Margaret H.; Forsyth, Richard D.; Plyley, Michael J. (1992). "Cold Water and Hot Iron: Trial by Ordeal in England". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 22 (4): 573–95. doi:10.2307/205237. JSTOR 205237.

- ^ Kerr, Margaret H.; Forsyth, Richard D.; Plyley, Michael J. (1992). "Cold Water and Hot Iron: Trial by Ordeal in England". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 22 (4): 3. doi:10.2307/205237. JSTOR 205237.

- ^ a b Groot, Roger D. (1982). "The Jury of Presentment Before 1215". The American Journal of Legal History. 26 (1): 23. doi:10.2307/844604. JSTOR 844604.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 67.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 127–28.

- ^ "Ma l'imperatore svevo fu conservatore o innovatore?" [But was the Swabian emperor a conservative or an innovator?]. Stupor Mundi (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ McAuley, Finbarr (1 October 2006). "Canon Law and the End of the Ordeal". Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. 26 (3): 473–514. doi:10.1093/ojls/gql015.

- ^ a b Leeson, Peter T. (August 2012). "Ordeals" (PDF). Journal of Law and Economics. 55 (3): 691–714. doi:10.1086/664010. JSTOR 10.1086/664010. S2CID 222330413. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Leeson, Peter (31 January 2010). "Justice, medieval style". Boston Sunday Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Brown, Peter (Spring 1975). "Society and the Supernatural: A Medieval Change". Daedalus. 104 (2): 135–38.

- ^ Brown, Peter (Spring 1975). "Society and the Supernatural: A Medieval Change". Daedalus. 104 (2): 143.

Further reading

[edit]- Bartlett, Robert (1986). Trial by Fire and Water: The Medieval Judicial Ordeal. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198219736. OCLC 570398111.

- Delmas-Marty, Mireille; Spencer, J. R., eds. (17 October 2002). European Criminal Procedures. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0-521-59110-2. OCLC 1025272735.

- Glitsch, Heinrich (1913). Mittelalterliche Gottesurteile (in German). Leipzig: R. Voigtländer. OCLC 10741467.

- Kadri, Sadakat (2005). The Trial: A History from Socrates to O.J. Simpson. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780375505508. OCLC 624723889.

- Kaegi, Adolf (1887). Alter und Herkunft des germanischen Gottesurteils (in German). Zurich: s.n. OCLC 82221961.

- Lea, Henry C. (1866). Superstition and Force. Philadelphia: Collins, Printer. OCLC 18128359.

- Miller, William Ian (1988). "Ordeal in Iceland". Scandinavian Studies. 60 (2): 189–218. JSTOR 40918943.

- Pilarczyk, Ian C. (1996). "Between a Rock and a Hot Place: Issues of Subjectivity and Rationality in the Medieval Ordeal by Hot Iron" (PDF). Anglo-America Law Review. 25: 87–112.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch