Packet forwarding

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2009) |

Packet forwarding is the relaying of packets from one network segment to another by nodes in a computer network.

Models

[edit]

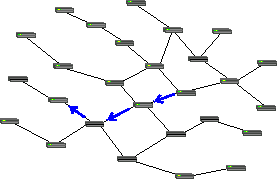

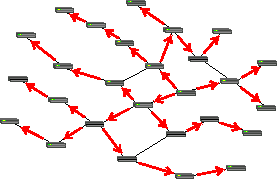

The simplest forwarding model—unicasting—involves a packet being relayed from link to link along a chain leading from the packet's source to its destination. However, other forwarding strategies are commonly used. Broadcasting requires a packet to be duplicated and copies sent on multiple links with the goal of delivering a copy to every device on the network. In practice, broadcast packets are not forwarded everywhere on a network, but only to devices within a broadcast domain, making broadcast a relative term. Less common than broadcasting, but perhaps of greater utility and theoretical significance, is multicasting, where a packet is selectively duplicated and copies delivered to each of a set of recipients.

Networking technologies tend to naturally support certain forwarding models. For example, fiber optics and copper cables run directly from one machine to another to form a natural unicast media – data transmitted at one end is received by only one machine at the other end. However, as illustrated in the diagrams, nodes can forward packets to create multicast or broadcast distributions from naturally unicast media. Likewise, traditional Ethernet (10BASE5 and 10BASE2, but not the more modern 10BASE-T) are natural broadcast media – all the nodes are attached to a single long cable and a packet transmitted by one device is seen by every other device attached to the cable. Ethernet nodes implement unicast by ignoring packets not directly addressed to them. A wireless network is naturally multicast – all devices within a reception radius of a transmitter can receive its packets. Wireless nodes ignore packets addressed to other devices, but require forwarding to reach nodes outside their reception radius.

Decisions

[edit]At nodes where multiple outgoing links are available, the choice of which, all, or any to use for forwarding a given packet requires a decision-making process that, while simple in concept, is sometimes bewilderingly complex. Since a forwarding decision must be made for every packet handled by a node, the total time required for this can become a major limiting factor in overall network performance. Much of the design effort of high-speed routers and switches has been focused on making rapid forwarding decisions for large numbers of packets.

The forwarding decision is generally made using one of two processes: routing, which uses information encoded in a device's address to infer its location on the network, or bridging, which makes no assumptions about where addresses are located and depends heavily on broadcasting to locate unknown addresses. The heavy overhead of broadcasting has led to the dominance of routing in large networks, particularly the Internet; bridging is largely relegated to small networks where the overhead of broadcasting is tolerable. However, since large networks are usually composed of many smaller networks linked together, it would be inaccurate to state that bridging has no use on the Internet; rather, its use is localized.

Methods

[edit]A node can use one of two different methods to forward packets: store-and-forward or cut-through switching.[1]

See also

[edit]- Equal-cost multi-path routing

- Forwarding information base

- Node-to-node data transfer

- Per-hop behaviour

- Port forwarding

References

[edit]- ^ Stefan Haas (1998). The IEEE 1355 Standard: Developments, Performance and Application in High Energy Physics (PDF) (Thesis). p. 58. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch