Page table

A page table is a data structure used by a virtual memory system in a computer to store mappings between virtual addresses and physical addresses. Virtual addresses are used by the program executed by the accessing process, while physical addresses are used by the hardware, or more specifically, by the random-access memory (RAM) subsystem. The page table is a key component of virtual address translation that is necessary to access data in memory. The page table is set up by the computer's operating system, and may be read and written during the virtual address translation process by the memory management unit or by low-level system software or firmware.

Role of the page table

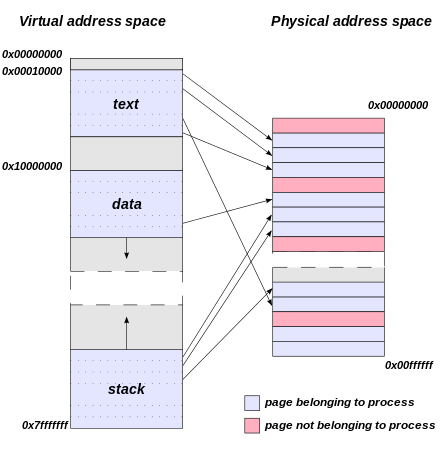

[edit]In operating systems that use virtual memory, every process is given the impression that it is working with large, contiguous sections of memory. Physically, the memory of each process may be dispersed across different areas of physical memory, or may have been moved (paged out) to secondary storage, typically to a hard disk drive (HDD) or solid-state drive (SSD).

When a process requests access to data in its memory, it is the responsibility of the operating system to map the virtual address provided by the process to the physical address of the actual memory where that data is stored. The page table is where mappings of virtual addresses to physical addresses are stored, with each mapping also known as a page table entry (PTE).[1][2]

The translation process

[edit]

The memory management unit (MMU) inside the CPU stores a cache of recently used mappings from the operating system's page table. This is called the translation lookaside buffer (TLB), which is an associative cache.

When a virtual address needs to be translated into a physical address, the TLB is searched first. If a match is found, which is known as a TLB hit, the physical address is returned and memory access can continue. However, if there is no match, which is called a TLB miss, the MMU, the system firmware, or the operating system's TLB miss handler will typically look up the address mapping in the page table to see whether a mapping exists, which is called a page walk. If one exists, it is written back to the TLB, which must be done because the hardware accesses memory through the TLB in a virtual memory system, and the faulting instruction is restarted, which may happen in parallel as well. The subsequent translation will result in a TLB hit, and the memory access will continue.

Translation failures

[edit]The page table lookup may fail, triggering a page fault, for two reasons:

- The lookup may fail if there is no translation available for the virtual address, meaning that virtual address is invalid. This will typically occur because of a programming error, and the operating system must take some action to deal with the problem. On modern operating systems, it will cause a segmentation fault signal being sent to the offending program.

- The lookup may also fail if the page is currently not resident in physical memory. This will occur if the requested page has been moved out of physical memory to make room for another page. In this case the page is paged out to a secondary store located on a medium such as a hard disk drive (this secondary store, or "backing store", is often called a swap partition if it is a disk partition, or a swap file, swapfile or page file if it is a file). When this happens the page needs to be taken from disk and put back into physical memory. A similar mechanism is used for memory-mapped files, which are mapped to virtual memory and loaded to physical memory on demand.

When physical memory is not full this is a simple operation; the page is written back into physical memory, the page table and TLB are updated, and the instruction is restarted. However, when physical memory is full, one or more pages in physical memory will need to be paged out to make room for the requested page. The page table needs to be updated to mark that the pages that were previously in physical memory are no longer there, and to mark that the page that was on disk is now in physical memory. The TLB also needs to be updated, including removal of the paged-out page from it, and the instruction restarted. Which page to page out is the subject of page replacement algorithms.

Some MMUs trigger a page fault for other reasons, whether or not the page is currently resident in physical memory and mapped into the virtual address space of a process:

- Attempting to write when the page table has the read-only bit set causes a page fault. This is a normal part of many operating system's implementation of copy-on-write; it may also occur when a write is done to a location from which the process is allowed to read but to which it is not allowed to write, in which case a signal is delivered to the process.

- Attempting to execute code when the page table has the NX bit (no-execute bit) set in the page table causes a page fault. This can be used by an operating system, in combination with the read-only bit, to provide a Write XOR Execute feature that stops some kinds of exploits.[3]

Frame table data

[edit]The simplest page table systems often maintain a frame table and a page table. The frame table holds information about which frames are mapped. In more advanced systems, the frame table can also hold information about which address space a page belongs to, statistics information, or other background information.

Page table data

[edit]The page table is an array of page table entries.

Page table entry

[edit]Each page table entry (PTE) holds the mapping between a virtual address of a page and the address of a physical frame. There is also auxiliary information about the page such as a present bit, a dirty or modified bit, address space or process ID information, amongst others.

Secondary storage, such as a hard disk drive, can be used to augment physical memory. Pages can be paged in and out of physical memory and the disk. The present bit can indicate what pages are currently present in physical memory or are on disk, and can indicate how to treat these different pages, i.e. whether to load a page from disk and page another page in physical memory out.

The dirty bit allows for a performance optimization. A page on disk that is paged in to physical memory, then read from, and subsequently paged out again does not need to be written back to disk, since the page has not changed. However, if the page was written to after it is paged in, its dirty bit will be set, indicating that the page must be written back to the backing store. This strategy requires that the backing store retain a copy of the page after it is paged in to memory. When a dirty bit is not used, the backing store need only be as large as the instantaneous total size of all paged-out pages at any moment. When a dirty bit is used, at all times some pages will exist in both physical memory and the backing store.

In operating systems that are not single address space operating systems, address space or process ID information is necessary so the virtual memory management system knows what pages to associate to what process. Two processes may use two identical virtual addresses for different purposes. The page table must supply different virtual memory mappings for the two processes. This can be done by assigning the two processes distinct address map identifiers, or by using process IDs. Associating process IDs with virtual memory pages can also aid in selection of pages to page out, as pages associated with inactive processes, particularly processes whose code pages have been paged out, are less likely to be needed immediately than pages belonging to active processes.

As an alternative to tagging page table entries with process-unique identifiers, the page table itself may occupy a different virtual-memory page for each process so that the page table becomes a part of the process context. In such an implementation, the process's page table can be paged out whenever the process is no longer resident in memory.

Page table types

[edit]There are several types of page tables, which are optimized for different requirements. Essentially, a bare-bones page table must store the virtual address, the physical address that is "under" this virtual address, and possibly some address space information.

Inverted page tables

[edit]An inverted page table (IPT) is best thought of as an off-chip extension of the TLB which uses normal system RAM. Unlike a true page table, it is not necessarily able to hold all current mappings. The operating system must be prepared to handle misses, just as it would with a MIPS-style software-filled TLB.

The IPT combines a page table and a frame table into one data structure. At its core is a fixed-size table with the number of rows equal to the number of frames in memory. If there are 4,000 frames, the inverted page table has 4,000 rows. For each row there is an entry for the virtual page number (VPN), the physical page number (not the physical address), some other data and a means for creating a collision chain, as we will see later.

Searching through all entries of the core IPT structure is inefficient, and a hash table may be used to map virtual addresses (and address space/PID information if need be) to an index in the IPT - this is where the collision chain is used. This hash table is known as a hash anchor table. The hashing function is not generally optimized for coverage - raw speed is more desirable. Of course, hash tables experience collisions. Due to this chosen hashing function, we may experience a lot of collisions in usage, so for each entry in the table the VPN is provided to check if it is the searched entry or a collision.

In searching for a mapping, the hash anchor table is used. If no entry exists, a page fault occurs. Otherwise, the entry is found. Depending on the architecture, the entry may be placed in the TLB again and the memory reference is restarted, or the collision chain may be followed until it has been exhausted and a page fault occurs.

A virtual address in this schema could be split into two, the first half being a virtual page number and the second half being the offset in that page.

A major problem with this design is poor cache locality caused by the hash function. Tree-based designs avoid this by placing the page table entries for adjacent pages in adjacent locations, but an inverted page table destroys spatial locality of reference by scattering entries all over. An operating system may minimize the size of the hash table to reduce this problem, with the trade-off being an increased miss rate.

There is normally one hash table, contiguous in physical memory, shared by all processes. A per-process identifier is used to disambiguate the pages of different processes from each other. It is somewhat slow to remove the page table entries of a given process; the OS may avoid reusing per-process identifier values to delay facing this. Alternatively, per-process hash tables may be used, but they are impractical because of memory fragmentation, which requires the tables to be pre-allocated.

Inverted page tables are used for example on the PowerPC, the UltraSPARC and the IA-64 architecture.[4]

Multilevel page tables

[edit]

The inverted page table keeps a listing of mappings installed for all frames in physical memory. However, this could be quite wasteful. Instead of doing so, we could create a page table structure that contains mappings for virtual pages. It is done by keeping several page tables that cover a certain block of virtual memory. For example, we can create smaller 1024-entry 4 KB pages that cover 4 MB of virtual memory.

This is useful since often the top-most parts and bottom-most parts of virtual memory are used in running a process - the top is often used for text and data segments while the bottom for stack, with free memory in between. The multilevel page table may keep a few of the smaller page tables to cover just the top and bottom parts of memory and create new ones only when strictly necessary.

Now, each of these smaller page tables are linked together by a master page table, effectively creating a tree data structure. There need not be only two levels, but possibly multiple ones. For example, a virtual address in this schema could be split into three parts: the index in the root page table, the index in the sub-page table, and the offset in that page.

Multilevel page tables are also referred to as "hierarchical page tables".

Virtualized page tables

[edit]It was mentioned that creating a page table structure that contained mappings for every virtual page in the virtual address space could end up being wasteful. But, we can get around the excessive space concerns by putting the page table in virtual memory, and letting the virtual memory system manage the memory for the page table.

However, part of this linear page table structure must always stay resident in physical memory in order to prevent circular page faults and look for a key part of the page table that is not present in the page table.

Nested page tables

[edit]Nested page tables can be implemented to increase the performance of hardware virtualization. By providing hardware support for page-table virtualization, the need to emulate is greatly reduced. For x86 virtualization the current choices are Intel's Extended Page Table feature and AMD's Rapid Virtualization Indexing feature.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Virtual Memory". umd.edu. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Page Table Management". kernel.org. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "W^X - The Mechanism".

- ^ William Stallings, Operating Systems Internals and Design Principles, p. 353.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrew S. Tanenbaum, Modern Operating Systems, ISBN 0-13-031358-0

- A. Silberschatz, P. B. Galvin, G. Gagne, Operating System Concepts, ISBN 0-471-69466-5

- Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces, by Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau and Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau. Arpaci-Dusseau Books, 2014. Relevant chapters: Address Spaces Address Translation Introduction to Paging TLBs Advanced Page Tables

- CNE Virtual Memory Tutorial, Center for the New Engineer George Mason University, Page Tables

- "Art of Assembler, 6.6 Virtual Memory, Protection, and Paging". Archived from the original on February 18, 2012.

- "Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manuals". Intel. January 18, 2018.

- "AMD64 Architecture Software Developer's Manual". AMD. Archived from the original on 2010-03-13.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch