Paleolithic Iberia

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

| ↓ Mesolithic |

The Paleolithic in the Iberian peninsula is the longest period of Iberian prehistory, spanning from c. 1.3 million years ago (Ma) to c. 11,500 years ago, ending at roughly the same time as the Pleistocene epoch. The Paleolithic was characterized by climate oscillations between ice ages and small interglacials, producing heavy changes in Iberia's orography.[1] Cultural change within the period is usually described in terms of lithic industry evolution.[2]

Archaeological sites containing Paleolithic remains are scattered throughout the Iberian peninsula. Atapuerca, an archaeological site near Burgos, constitutes the most abundant and earliest evidence of humankind in Europe, with a rich array of fossils, artifacts, and art dating back nearly one million years. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 2000.[3]

Lower Paleolithic

[edit]The Lower Paleolithic (c. 1.3 Ma – 128 ka ago) is the earliest and longest subdivision of the Paleolithic, spanning most of the Calabrian (c. 1.8 Ma – 770 ka ago) and Chibanian (c. 770 – 126 ka ago) stages. This timespan is mainly studied from fossils of the genus Homo and from lithic tools found at archaeological sites. The Calabrian in Iberia was characterized by a warm climate similar to the modern Mediterranean, and the faunal landscape was similar to that of the current African savanna, with large mammals including elephants, saber-toothed cats, hippopotamuses, and hyenas. In the Chibanian, glaciation caused major changes to the landscape and ecological conditions, leading to the dominance of mammals including rhinoceroses, cave bears, and mammoths.[4]

Iberia was mostly populated by Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis during this period. The two main hypotheses for their arrival are that they crossed from Africa via Gibraltar or from Europe through the Pyrenees.[5] Homo antecessor would be the last common ancestor of our species, Homo sapiens, and Homo heidelbergensis, who would have evolved into Homo neanderthalensis.[6][disputed – discuss] Some research suggests two long periods of depopulation of the peninsula (between c. 1.2 Ma and 800 ka ago and between c. 800 and 600 ka ago).[1][failed verification]

Oldowan

[edit]The archaic Lower Paleolithic (c. 1.3 Ma – 550 ka ago) corresponds to Oldowan or Mode 1 stone tools, usually called choppers.[1] Both Homo fossils and lithic instruments dating from this period have been found in Iberia. The most ancient of the fossils are a partial mandible of an unidentified Homo species (c. 1.2 Ma ago) and a maxilla still[as of?] pending identification (c. 1.4 Ma ago), both discovered in Sima del Elefante, Atapuerca.[4][7]

Atapuerca also hosts several lithic tools from this period, mainly from flint, quartzite, sandstone, quartz and limestone. The flint presents two variations, one of Neogene origins and the other from the Cretaceous, and the rest of materials were transported from the fluvial terraces of Arlanzón and Vena, 1 kilometer from the site.[8] The oldest lithic tool remains (c. 1.2 Ma ago) are simple lithic cores and flakes, mainly of flint, from TE9 at Sima del Elefante. Level TD6 of Gran Dolina (c. 850 ka ago) features lithic tools of more varied materials and functions, such as denticulate tools and scrapers and one limestone chopper.[8]

Level TD6 of Gran Dolina also contains fossils from c. 11 Homo antecessor individuals aged approximately 4 to 16, dated to c. 850 ka ago.[9] They present with similar stone tool marks to those on animal fossils, indicating extraction of the spinal cord and thus constituting the first evidence of cannibalism in the Homo genus.[6] Another significant archeological site for this period is Guadix-Baza (Andalusia), with Mode 1 stone tools, Calabrian fauna with evidence of manipulation, and a human molar dated c. 1.4 Ma ago.[1]

Acheulean

[edit]The classical Lower Paleolithic (c. 550 – 128 ka ago) corresponds to Acheulean or Mode II stone tools, of which the best representative is the biface. This industry first appeared in Iberia at Barranc de la Boella (Catalonia) c. 900 ka ago and mostly consisted of choppers and rough bifaces. As such, the lithic tools from Barranc de la Boella are known as archaic Acheulean, in contrast with the more advanced tools at Galería in Atapuerca.[8] Here, there was an advantageous natural trap used to obtain food, used not for habitation but to process herbivores that had fallen through it, so discovered tools consist mainly of bifaces and cleavers.[10][clarification needed]

At Sima de los Huesos, fossils dated c. 430 ka ago have been identified as an estimated 30 Homo heidelbergensis individuals.[6] Among them, one of the most well preserved is Miguelón or Skull 5. The site also contains thousands of bones from Ursus deningeri, ancestor of the cave bear, among those from other smaller carnivores. Neither evidence of habitation nor of a catastrophic event has been found at the site, so it has been hypothesized that the pit constitutes the first deliberate burial of bodies among Homo.[6] Mitochondrial DNA analysis, possible due to favorable temperature and humidity preservation conditions at the site, showed striking similarities to Denisovan mitochondrial DNA and requires further research.[6] By contrast, nuclear DNA collected from the individuals is more similar to that of the eventual Homo neanderthalensis, suggesting continual hybridization among the different Homo species.[9]

The westernmost known remains of Homo heidelbergensis in Europe are found at the Cave of Aroeira (Santarém), dated c. 400 ka ago, along with evidence of controlled fire.[1][5] Similar evidence for fire use was found at Torralba and Ambrona (Soria) along with lithic tools and animal fossil remains, including elephant, with and without evidence of human manipulation.

Middle Paleolithic

[edit]The Middle Paleolithic (c. 128 ka – 40 ka ago) in Iberia was characterized by extended occupation by Homo neanderthalensis, who had heavier bodies, higher lung volume, and bigger brains than Homo sapiens. Important archaeological sites containing Neanderthal fossils are Sidrón Cave (Asturias), Pinilla del Valle (Madrid) and Sima de las Palomas (Murcia).[5] Gorham's cave (Gibraltar) contains Neanderthal rock art, suggesting they were more capable of symbolic thought than previously thought. This period, like the previous one, is mainly studied from fossils and stone tools.

Mousterian

[edit]Five different techniques constitute the Mode 3 or Mousterian lithic tool industry: Levallois, discoid, Quina, laminar, and bifacial, the first three being the more frequent in Iberia. In contrast to the Lower Paleolithic, when habitational places were usually in open air and caves were used circumstantially (such as for burial, tool fabrication, or butchering), caves were increasingly used for habitation in the Mousterian, with remains of home conditioning such as archaic cobblestones (Cave of Els Ermitons) or stub walls (Cave of Morín).[1] There is no evidence of extended usage of bone or antlers for tool fabrication, and because of decomposition, very little evidence of wood usage has survived.

Further heterogeneity among sites also starts appearing: some sites show evidence of occupation by several generations over long periods of time—for example, Cova Negra (Valencia); others were used for animal butchering, similarly to Lower Paleolithic sites; others were primitive lithic tool manufacturing workshops, such as Cantera Vieja (Madrid); and, finally, others mainly served for seasonal logistics, taking into account animal migrations, such as Cova Gran (Lleida).[clarification needed]

Mousterian archaeological sites can also be found towards the end of the Lower Paleolithic, between 350 ka and 128 ka ago; however, they are scarcer, concentrated over the coast and nonexistent in most of the southwestern quadrant of the peninsula. Although in the present these sites are on the waterfront, during glacial marine regressions they may have served as lookouts for what would have been kilometer-long marshes.[1] Mousterian fossils are also found at Atapuerca, in Cueva Fantasma (c. 60 ka ago) and Galería de las Estatuas (c. 110 – 80 ka ago), although they are recent findings and require further research.[9]

Châtelperronian

[edit]The Châtelperronian industry, mostly found in southern France, is contemporaneous to the period of time when both Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens coexisted in Europe, and thus at first it was attributed to the latter, but the discovery of a full Neanderthal skeleton in a Châtelperronian context changed the attribution to Homo neanderthalensis.[11] Some academics prefer to call it late Mousterian, and there is debate over whether to consider it a proper or a transitional industry, since chronologically it belongs to middle Paleolithic but it shows characteristics of upper Paleolithic industries.[11]

This industry extended into northern Iberia, although it is not as well represented. Escoural Cave (Évora) contains evidence of human activity c. 47 ka ago.[12] A Neanderthal skull was found in Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar in 1848, making it the second territory after Belgium where remains of Neanderthals were found. Further discoveries of Neanderthals in Gibraltar have been made at Devil's Tower Cave.[13] Evidence of their presence in this period is found in Columbeira, Figueira Brava and Salemas.[14] The Cave of Salemas and the Cave of Pego do Diabo, both located in Loures Municipality, were inhabited in the Paleolithic.[15]

Upper Paleolithic

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Inconsistent date notation, unclear wording, unsourced claims. (July 2024) |

It is unclear whether radiocarbon dates in this article are calibrated or not. (July 2024) |

The first remains of Homo sapiens appear in Iberia around 35 ka ago during the Upper Paleolithic (c. 40 ka – 11.5 ka ago). Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis coexisted for about 5,000 years, after which time H. neanderthalensis no longer appears in the fossil or archaeological record, indicating extinction.[5] Some have suggested[who?] that the newer remains[clarification needed] in Iberia suggest Neanderthals were driven out of Central Europe by Homo sapiens to the Iberian peninsula, where they took refuge. Middle Paleolithic archaeological industries lasted until about 28 ka or 26 ka BC in Iberia. A Neanderthal mandible (30 ka BP) and Mousterian tools (27 ka BP) were found in Zafarraya (Andalusia). Châtelperronian remains are found in Cantabria and Catalonia.

Aurignacian

[edit]The Aurignacian industry, sometimes called Mode 4, lasted c. 40 – 28 ka ago.[1] The first phase, sometimes called archaic Aurignacian or proto-Aurignacian, is contemporary with late Châtelperronian findings and still shares many lithic tools with Mode 3. It is mainly found in northern Iberia (current Cantabria, Asturias, Basque Country, and Catalonia).[16] Around 36 ka ago, it becomes more differentiated and can scarcely be found in Iberia's interior, maybe because of a second wave of Homo Sapiens coming from Europe.[citation needed] The most common findings are antler or bone assegais along with fine flint blades and long scrapers. Mode 4 becomes finally consolidated around 31 ka ago,[clarification needed] and archaeological sites are found scattered throughout Iberia.[1]

Some examples of Aurignacian archaeological sites are the Cave of Morín (Cantabria), the Cave of El Pendo (Cantabria), the Cave of El Castillo (Cantabria), Santimamiñe (Basque Country), Gorham's Cave (Gibraltar), Cova de Les Mallaetes (Valencia), and the Cave of Pego do Diablo (Lisbon). The remains of a child dated c. 24.5 ka ago, known as the Lapedo child, were discovered in Lagar Velho (Leiria), presenting a mosaic of Homo sapiens and Neanderthal features. There is no academic consensus on whether the individual was an hybrid.[16][14][as of?] By the end of the Aurignacian, Homo neanderthalensis had disappeared from Iberia.

Gravettian

[edit]The Gravettian (28 – 21 ka ago)[1] expanded from eastern Europe to Iberia as the Aurignacian did previously. The Gravettian in Iberia coincided with the Last Glacial Maximum, during which eastern and western Europe became isolated from each other.[citation needed] As such, the Gravettian evolved into the Solutrean in Iberia, whereas in Eastern Europe it evolved into the Epigravettian.[1]

Gravettian artifacts are not very abundant in the Cantabrian area (north), while in the southern region they are more common. In the Cantabrian area all Gravettian remains belong to late evolved phases[definition needed] and are always found mixed with Aurignacian technology. Gravettian sites are mainly found in the Basque Country (Lezetxiki, Bolinkoba), Cantabria (Morín, El Pendo, El Castillo), and Asturias (Cueto de la Mina). It is archaeologically split into two phases characterized by the amount of Gravettian elements: phase A has a 14

C date of c. 20,710 BP and phase B succeeds it.

The Cantabrian Gravettian has been compared to the Perigordian V-VII of the French sequence. It eventually vanishes from the archaeological sequence and is replaced by an "Aurignacian renaissance", at least in El Pendo cave.[citation needed] It is considered "intrusive", in contrast with the Mediterranean area, where it probably means a real colonization.[17]

The Gravettian culture also arrived late in the Mediterranean region. Nevertheless, southeastern Iberian has a number of important Gravettian sites, particularly in Valencia (Les Mallaetes, Parpaló, Barranc Blanc, Meravelles, Coba del Sol, Ratlla del Musol, Beneito). It is also found in Murcia (Palomas, Palomarico, Morote) and Andalusia (Los Borceguillos, Zájara II, Serrón, Gorham's Cave).

The first indications of modern human colonization of the interior and the west of the peninsula are found in this cultural phase, with a few late Gravettian elements found in the Manzanares valley (Madrid) and Salemas cave (Alentejo).

Solutrean

[edit]The Solutrean industry (21 – 17 ka ago)[1] first appears in Laugerie Haute (Dordogne, France) and Les Mallaetes (Valencia), with radiocarbon dates of 21,710 and 20,890 BP respectively.[17] In the Iberian peninsula it consists of three different facies.

The Iberian or Mediterranean facies is defined by the sites of Parpalló and Les Mallaetes in Valencia. They are immersed in Gravettian perdurations[clarification needed] that would eventually redefine the facies as "Gravettizing Solutrean."[17] The archetypical sequence, that of Parpalló and Les Mallaetes caves, is:

- Initial Solutrean.

- Full or Middle Solutrean, dated in its lower layers to 20,180 BP.

- A sterile layer with signs of intense cold related to the Last Glacial Maximum.

- Upper or Evolved Solutrean, including bone tools and bone needles.

These two caves are surrounded by many other sites (Barranc Blanc, Meravelles, Rates Penaes, etc.) that show only limited Solutrean influence and instead have many Gravettian perdurations[clarification needed], a convergence known as "Gravetto-Solutrean".

The Solutrean is also found in Murcia, Mediterranean Andalusia, and the lower Tagus (Portugal). In the Portuguese case there are no signs of Gravettization.

The Cantabrian facies shows two markedly different tendencies in Asturias and the Vasco-Cantabrian area. The oldest findings are all in Asturias and lack the initial phases, beginning with the full Solutrean in Las Caldas (Asturias) and nearby sites, followed by evolved Solutrean, with many unique regional elements. Radiocarbon dates oscillate between 21 and 19 ka BP.[17]

In the Vasco-Cantabrian area, the Gravettian influences seem persistent and the typical Solutrean foliaceous elements are minor. Some transitional elements that prelude the Magdalenian, like the monobiselated bone spear point, are already present. Important sites are Altamira, Morín, Chufín, Salitre, Ermittia, Atxura, Lezetxiki, and Santimamiñe.

In northern Catalonia there is an early local Solutrean industry, followed by scarce middle elements but with a well-developed final Solutrean. It is related to the French Pyrenean sequences. The main sites are Cau le Goges, Reclau Viver, and L'Arbreda.

In the region of Madrid there were some findings attributed to Solutrean that are today missing.[further explanation needed]

Magdalenian

[edit]

The Magdalenian industry lasted c. 17 – 11.5 ka ago.[1]

In the Cantabrian area, the early Magdalenian phases show two different facies: the "Castillo facies" evolves locally over final Solutrean layers, while the "Rascaño facies" appears in most cases directly over the natural soil (no earlier occupations of these sites).

In the second phase, the lower evolved Magdalenian, there are also two facies but now with a geographical divide: the "El Juyo facies" is found in Asturias and Cantabria, while the "Basque Country facies" is only found in this region.

The dates for this early Magdalenian period oscillate between 16,433 BP for the Rascaño facies in Rascaño cave, 15,988 and 15,179 BP for the El Juyo facies in the same cave, and 15 ka BP for Castillo facies in Altamira. The facies in the Cave of Abauntz in the Basque Country has given 15,800 BP.[17]

The middle Magdalenian shows fewer findings.

The upper Magdalenian is closely related to that of southern France (Magdalenian V and VI), being characterized by the presence of harpoons. Again there are two facies (called A and B) that appear geographically intertwined, though the facies A (dates: 15,400–13,870 BP) is absent in the Basque Country and the facies B (dates 12,869–12,282 BP) is rare in Asturias.[citation needed]

In Portugal there have been some findings of the upper Magdalenian north of Lisbon, at Casa da Moura and Lapa do Suão. A possible intermediate site is La Dehesa (Salamanca), which is clearly associated with that[clarification needed] of the Cantabrian area.

In the Mediterranean area, Catalonia is directly connected with the French sequence in the late phases. The rest of Catalonia shows a unique local evolution known as Parpallense.

The so-called "Parpalló Magdalenian", extending throughout the southeast, is actually a continuation of the local Gravetto-Solutrean. Only the late upper Magdalenian actually includes true elements of this culture, like proto-harpoons. Radiocarbon dates for this phase are c. 11,470 BP (Borran Gran). Other sites give later dates that approach the Epipaleolithic.[17]

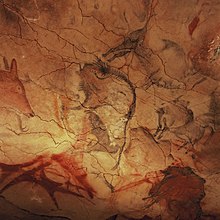

Art

[edit]Paleolithic cave and rock art has survived in Iberia until the present day. Altamira Cave is the most well-known example of the former, being a World Heritage Site since 1985.[18] The earliest examples, like the Caves of Monte Castillo (Cantabria), date to Aurignacian times. L'Arbreda Cave in Catalonia contains Aurignacian cave paintings as well as earlier remains from Neanderthals.

The practice of mural art increased in frequency in the Solutrean period, when the first animals were depicted, but it became truly widespread in the Magdalenian, being found in almost every cave.

Most of the representations are of animals (bison, horse, deer, bull, reindeer, goat, bear, mammoth, moose) and are painted in ochre and black colors, but there are exceptions, including human-like forms. Abstract drawings also appear in some sites.

In the Mediterranean and interior areas, mural art is not as abundant but can still be found starting in the Solutrean.

Côa Valley, in current Portugal, and Siega Verde, in current Spain, formed around tributaries into Douro, contain the best preserved rock art. As a pair, they have been a World Heritage Site since 1998.[19] They contain petroglyphs, dating to 22 ka ago, that document continuous human occupation from the end of the Paleolithic Age. The sites together contain thousands of animal figures carved over several millenia.[19]

Other sites with surviving cave and rock art include Chimachias, Los Casares or La Pasiega, or, in general, the cave sites in Cantabria.

See also

[edit]- Paleontology

- Timeline of human evolution

- Paleolithic religion

- Art of the Upper Paleolithic

- Art of the Middle Paleolithic

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Menéndez, Mario (2019). Prehistoria de la Península Ibérica : el progreso de la cognición, el mestizaje y las desigualdades durante más de un millón de años. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. ISBN 978-84-9181-602-7. OCLC 1120111673.

- ^ Clark, Grahame (1977). World prehistory: In new perspective (An illustrated 3d ed.). Cambridge [Eng]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-21506-4. OCLC 2984089.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Atapuerca". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Prehistoria" (in Spanish). National Geographic Institute (Spain). Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ a b c d Crespo Garay, Cristina (2021-11-27). "¿Qué homínidos han poblado España a lo largo de la historia?" (in European Spanish). National Geographic. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- ^ a b c d e Lorenzo, Carlos (2022). "Los homininos de Atapuerca. Caracterización y genética". Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia. 45: 16–21. ISSN 2387-1237.

- ^ "Encuentran en Atapuerca la cara del Primer Europeo". www.atapuerca.org (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ a b c García Medrano, Paula (2022). "Tecnología y evolución de las herramientas en Atapuerca". Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia (in European Spanish). 45: 50–55. ISSN 2387-1237.

- ^ a b c Mosquera Martínez, Marina (2022). "El comportamiento social de los homininos". Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia. 45: 30–37. ISSN 2387-1237.

- ^ Carbonell i Roura, Eudald (2022). "Atapuerca. Historia y futuro". Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia. 45: 6–15. ISSN 2387-1237.

- ^ a b Roussel, M.; Soressi, M.; Hublin, J. -J. (2016-06-01). "The Châtelperronian conundrum: Blade and bladelet lithic technologies from Quinçay, France". Journal of Human Evolution. 95: 13–32. Bibcode:2016JHumE..95...13R. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.003. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 27260172.

- ^ "Gruta do Escoural". DGPC. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Garrod, Dorothy A. E.; Buxton, L. H.; Smith, E. Elliot; Bate, Dorothea M. A. (1928). "Excavation of a Mousterian Rock-shelter at Devil's Tower, Gibraltar". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 58. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland: 33–113. JSTOR 4619528.

- ^ a b Ian Tattersall, Jeffrey H. Schwartz (22 June 1999). "Hominids and hybrids: The place of Neanderthals in human evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (13). National Academy of Sciences: 7117–7119. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7117T. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7117. PMC 33580. PMID 10377375.

- ^ "Gruta de Salemas". Portal do Arqueólogo (in Portuguese). IGESPAR. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ a b Duarte, Cidália; Maurício, João; Pettitt, Paul B.; Souto, Pedro; Trinkaus, Erik; van der Plicht, Hans; Zilhão, João (1999-06-22). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in Iberia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7604–7609. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7604D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462.

- ^ a b c d e f F. Jordá Cerdá et al., Historia de España I: Prehistoria, 1986. ISBN 84-249-1015-X

- ^ "Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ^ a b "Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch