People's Grocery lynchings

The People's Grocery lynchings of 1892 occurred on March 9, 1892, in Memphis, Tennessee, when black grocery owner Thomas Moss and two of his workers, Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell, were lynched by a white mob while in police custody. The lynchings occurred in the aftermath of a fight between whites and blacks and two subsequent shooting altercations in which two white police officers were wounded.[1]

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

The store was located just outside Memphis in a neighborhood called the "Curve".[2] Opened in 1889, the People's Grocery was a cooperative venture run along corporate lines and owned by 11 prominent African Americans, including postman Thomas Moss, a friend of Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell.[3][4][5]

Timeline leading up to the lynching

[edit]March 2–4, 1892

[edit]By the 1890s, there were increasing racial tensions in the Curve neighborhood that spilled over between Thomas Moss, a successful black grocer, and William Barrett, a white grocer. Barrett's grocery had a virtual monopoly prior to Moss's venture, despite Barrett's bad reputation as a "low-dive gambling den" and a location where liquor could be illegally purchased.[2][6]

On Wednesday, March 2, 1892, trouble began when a young black boy, Armour Harris, and a young white boy, Cornelius Hurst, got into a fight over a game of marbles outside People's Grocery. When the white boy's father stepped in and began beating the black boy, two black workers from the grocery (Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell) came to his defense. More blacks and whites joined the fray, and at one point William Barrett was clubbed. He identified Will Stewart as his assailant.[7][8]

On Thursday, March 3, Barrett returned to the People's Grocery with a police officer and the two were met by Calvin McDowell. McDowell told them no one matching Stewart's description was within the store. The frustrated Barrett hit McDowell with his revolver and knocked him down, dropping the gun in the process. McDowell picked it up and shot at Barrett, but missed.[9] McDowell was subsequently arrested but released on bond on March 4. Warrants were also issued for Will Stewart and Armour Harris.[2]

The warrants enraged the black residents of the neighborhood who called a meeting during which they vowed to clean out the neighborhood's "damned white trash", which Barrett brought to the authorities' attention as evidence of a black conspiracy against whites.[8]

March 5–8, 1892

[edit]On Saturday, March 5, Judge Julius DuBose, a former Confederate soldier, was quoted in the Appeal-Avalanche newspaper as vowing to form a posse to get rid of the "high-handed rowdies" in the Curve.[9] That same day John Mosby, a black painter, was fatally shot after an altercation with a clerk in another white grocery in the Curve; as reported in the Appeal-Avalanche, Mosby cursed at the clerk after being denied credit for a purchase and the clerk responded by punching him.[9] Mosby returned that evening and hit the clerk with a stick, whereupon the clerk shot him.[9][10]

The People's Grocery men were increasingly concerned about an attack upon them, based on Dubose's threat and the Mosby shooting. They consulted a lawyer but were told since they were outside the city limits they could not depend on police protection and should prepare to defend themselves.[7]

On the evening of March 5, six armed white men—including a county sheriff and recently deputized plainclothes civilians—headed toward the People's Grocery. White papers[clarification needed] claimed their purpose was to inquire after Will Stewart and arrest him if he was there. In an account written by five black ministers in the St. Paul Appeal, the men were said to arrive with a rout in mind, for they had first gone to William Barrett's place then divided up and surreptitiously posted themselves at the front and back entrance to the People's Grocery.[8] The men inside, already anticipating a mob attack, were being surrounded by armed whites and did not know they were officers of the law.

When the whites entered the store they were shot at and several were hit; McDowell was captured at the scene and identified as an assailant. The black postman Nat Trigg was seized by deputy Charley Cole but Trigg shot Cole in the face blinding him in one eye, and Trigg managed to escape. The injured whites retreated to Barrett's store and more deputized whites were dispatched to the grocery where they eventually arrested thirteen blacks and seized a cache of weapons and ammunition.

Reports in white papers[clarification needed] described the shooting as a cold-blooded, calculated ambush by the blacks and, though none of the deputies had died, they predicted the wounds of Cole and Bob Harold, who was shot in the face and neck, would prove fatal. The five ministers writing in theSt. Paul Appeal said as soon as the black men realized the intruders were law officers they dropped their weapons and submitted to arrest, confident they would be able to explain their case in court.[8]

March 5–8, 1892

[edit]On Sunday, March 6, hundreds of white civilians were deputized and fanned out from the grocery to conduct a house-to-house search for blacks involved in "the conspiracy". They eventually arrested forty black people, including Armour Harris and his mother, Nat Trigg, and Tommie Moss. The story in the black paper contended that Moss was tending his books at the back of the store on the night of the shooting and couldn't have seen what happened when the whites arrived. When he heard gunshots he left the premises. In the eyes of many whites, however, Moss' position as a postman and the president of the co-op made him a ringleader of the conspiracy. He was also indicted in the white press for an insolent attitude when he was arrested.

Upon news of the arrest armed whites congregated around the fortress-like Shelby County Jail. Members of the black Tennessee Rifles militia also posted themselves outside the jail to keep watch and guard against a lynching. On Monday, March 7, Tommie's pregnant wife Betty Moss came to jail with food for her husband, but was turned away by Judge DuBose who told her to come back again in three days. On Tuesday, March 8, lawyers for several of the black men filed writs of habeas corpus but DuBose quashed them.

After news filtered out that the injured deputies were not going to die the tensions outside the jail seemed to abate and the Tennessee Rifles thought it was no longer necessary to guard the jail grounds, especially as the Shelby County Jail itself was thought to be impregnable. But, as Ida B. Wells would write in retrospect,[where?] the news that the deputies would survive was actually a catalyst for violence for the black men could not now be legally executed.

The lynching, March 9, 1892

[edit]

On Wednesday, March 9, at about 2:30 a.m. 75 men in black masks surrounded the Shelby County Jail and nine entered. They dragged Tommie Moss, Will Stewart, and Calvin McDowell from their cells and brought them to a Chesapeake & Ohio railroad yard a mile outside of Memphis.[11] What followed was described in such harrowing detail by white papers[clarification needed] that it was clear reporters had been called in advance to witness the lynching.

At the railroad yard McDowell "struggled mightily" and at one point managed to grab a shotgun from one of his abductors.[This quote needs a citation] After the mob wrested it from him they shot at his hands and fingers "inch by inch" until they were shot to pieces. Replicating the wounds the white deputies had suffered they shot four holes into McDowell's face, each large enough for a fist to enter. His left eye was shot out and the "ball hung over his cheek in shreds."[This quote needs a citation] His jaw was torn out by buckshot. Where "his right eye had been there was a big hole which his brains oozed out."[This quote needs a citation] The account by the five ministers in the Appeal-Avalanche added that his injuries were in accord with his "vicious and unyielding nature."[8]

Will Stewart was described as the most stoic of the three, "obdurate and unyielding to the last."[This quote needs a citation] He was also shot on the right side of the neck with a shotgun, and was shot with a pistol in the neck and left eye. Moss was also shot in the neck; his dying words, reported in the papers, were: "Tell my people to go West, there is no justice for them here."[12][13]

Aftermath

[edit]The murders led to increasing grief and unrest among the black population, along with rumors that blacks planned to meet at the People's Grocery and take revenge against whites. Judge DuBose ordered the sheriff to take possession of the swords and guns belonging to the Tennessee Rifles and to dispatch a hundred men to the People's Grocery where they should "shoot down on sight any Negro who appears to be making trouble."[This quote needs a citation] Gangs of armed white men rushed to the Curve and began shooting wildly into any groups of blacks they encountered, then looted the grocery. Subsequently, the grocery was sold for one-eighth its cost to William Barrett.

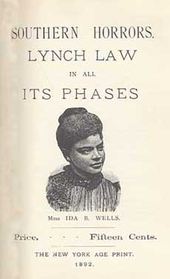

The lynching became a front-page story in the New York Times on March 10, which countered the image of the "New South" that Memphis was trying to promote. The lynching sparked national outrage, and Ida B. Wells' editorial, Free Speech, embraced Moss' dying words, which encouraged blacks to leave. "Following the advice of the Free Speech, people left the city in great numbers."[14] Lastly, Wells-Barnett had a personal connection to Moss and his wife as they were dear friends.[15]

This sparked an emigration movement that eventually saw 6,000 blacks leave Memphis for the Western Territories.[1] At a meeting of one thousand people at Bethel A. M. E. Church in Chicago in response to this lynching as well as two earlier lynchings (Ed Coy in Texarkana, Arkansas, and a woman in Rayville, Louisiana), a call by the presiding minister for the crowd to sing the then de facto national anthem, "America (My Country, 'Tis of Thee)" was refused in protest, and the song, "John Brown's Body" was substituted.[16][17] The widespread violence and particularly the murder of her friends drove Wells to research and document lynchings and their causes. She began investigative journalism by looking at the charges given for the murders, which officially started her anti-lynching campaign.[7]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b DeCosta-Willis.

- ^ a b c Giddings, Sword Among Lions, 2008.

- ^ Giddings, Paula (2006). When and where I enter: the impact of black woman on race and sex in America (Reprinted in Amistad ed.). New York, NY: Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-688-14650-4.

- ^ Peavey & Smith, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Hale, p. 208.

- ^ Appeal-Avalanche, March 10, 1892.

- ^ a b c Duster, Alfreda.

- ^ a b c d e Appeal (St. Paul), March 26, 1892.

- ^ a b c d Appeal-Avalanche, March 6, 1892.

- ^ Appeal-Avalanche, March 7, 1892.

- ^ Prasad.

- ^ Wells–Duster 1970, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Pinar, Ch 7, 2001, p. 465.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases, by Ida B. Wells-Barnett". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

- ^ Giddings, Paula. ""To Sell My Life as Dearly as Possible": Ida B. Wells and the First Antilynching Campaign" (PDF).

- ^ World, The (New York).

- ^ Morning Herald-Dispatch.

References linked to notes

[edit]Books, journals, magazines, and academic papers

- Giddings, Paula J. (2008). Ida: A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching. Amistad Press. ISBN 978-0-0619-7294-2. OCLC 865473600.

- DeCosta-Willis, Miriam (March 1, 2018) [October 8, 2017]. "Ida B. Wells-Barnett". Tennessee Encyclopedia (online). Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "Alfreda Wells discusses her mother, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her book 'Crusade for Justice'" (verbal transcript and sound recording) (radio transcript). Chicago: Studs Terkel Radio Archive at WFMT.

- Hale, Grace Elizabeth, PhD (1998). Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South 1890–1940 (reprint ed.). New York: Vintage Books (Knopf Doubleday). p. 208. ISBN 0-6797-7620-6. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

Originally published by the University of Virginia

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Peavey, Linda; Smith, Ursula (April 2019). "A Determined Quest for Equality – How Ida B. Wells Battled Jim Crow in Memphis". Memphis (monthly magazine). 44 (1). Contemporary Media: 46–49. Retrieved October 25, 2020. Alternate link via ISSUU (a version of this story was published in the June 1983 issue of Memphis).

- Pinar, William Frederick, PhD (January 2001). "7 – Black Protest and the Emergence of Ida B. Wells". Counterpoints. 163 – The Gender of Racial Politics and Violence in America: Lynching, Prison Rape, & the Crisis of Masculinity. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang: 419–486. ISSN 1058-1634. JSTOR 42977757. OCLC 5792454104. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pinar, William Frederick, PhD (January 2001). "8 – White Women and the Campaign Against Lynching: Frances Willard, Jane Addams, Jesse Daniel Ames". Counterpoints. 163 – The Gender of Racial Politics and Violence in America: Lynching, Prison Rape, & the Crisis of Masculinity. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang: 487–554. ISSN 1058-1634. JSTOR 42977758. OCLC 5792541764. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Prasad, Mahendra (n.d.) [2015]. "How the Location of the Peoples Grocery Lynching Was Rediscovered" (online). Memphis, Tennessee: The Lynching Sites Project of Memphis. Retrieved July 11, 2019 – via lynchingsitesmem.org.

- Wells, Ida Bell (1970). Duster, Alfreda (ed.). Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-89344-8. LCCN 73108837. OCLC 8162296586. Retrieved September 8, 2019 – via Internet Archive (Negro American Biographies and Autobiographies Series. John Hope Franklin, Series Editor)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

News media

- Appeal-Avalanche, The (March 6, 1892). "A Bloody Riot – Deputies Shot by Negroes". The Appeal-Avalanche. Vol. 52, no. 34. Memphis. p. 1 (cols. 1–2). ISSN 2574-2671. LCCN sn86071412. OCLC 13516304. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Appeal-Avalanche, The (March 7, 1892). "Quite at the Curve". The Appeal-Avalanche. Vol. 52, no. 35. Memphis. p. 4 (cols. 5–6). ISSN 2574-2671. LCCN sn86071412. OCLC 13516304. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Appeal-Avalanche, The (March 10, 1892). "The Mob's Work – Done With Guns, Not Ropes". The Appeal-Avalanche. Vol. 52, no. 38. Memphis. pp. 3 (cols. 1–4) & 3 (cols. 2–3). ISSN 2574-2671. LCCN sn86071412. OCLC 13516304. Retrieved June 19, 2020 – via The Lynching Sites Project of Memphis lynchingsitesmem.org).

- Appeal (St. Paul) (March 26, 1892). "Memphis Mob". The Appeal. Vol. 8. St. Paul and Minneapolis. pp. 1 & 4. ISSN 2163-7075. LCCN sn83016810. OCLC 10157486. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Morning Herald-Dispatch, The (March 29, 1892). "Not Their Country – Chicago Negroes Refuse to Sing 'My Country, 'Tis of Thee'". Herald and Review. Vol. 12, no. 150. Decatur, Illinois. p. 1. Retrieved March 23, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- World, The (evening edition) (March 28, 1892). "Wouldn't Sing 'America' – Net Yet 'Sweet Land of Liberty,' Say a Thousand Chicago Negroes". The Evening World. Vol. 32, no. 11, 178. New York: Press Publishing Company. AP. p. 3 (col. 6). ISSN 1941-0654. LCCN sn83030193. OCLC 9368601 – via Newspapers.com.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch