Peter Baker (slave trader)

Peter Baker (1731–1796) was a privateer, shipbuilder, Lord Mayor of Liverpool, and notable English slave trader.[1][2] He formed the Liverpool shipbuilding company Baker and Dawson with his son-in-law John Dawson. Baker was a figure of political importance in Liverpool history at a time when Liverpool was the foremost slave trading hub of the UK. Baker was part of the Corporation of Liverpool, one of the UK's largest slave trading enterprises, at a time when the corporation was opposing the first meaningful actions taken by the UK House of Lords to abolish slavery. Baker and Dawson were most active between 1783-1792 as two of the largest slave trading figures in the Corporation of Liverpool, enslaving many thousands of people. In 1795, Baker became Lord Mayor of Liverpool, before passing away the next year.

Slave trade

[edit]

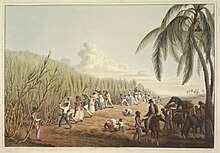

Peter Baker was born in West Derby, Liverpool.[3] In the period between 1783 and 1792, Baker and his partner John Dawson were the largest firm of slave traders in England.[4] In 1784 their firm, Baker and Dawson, secured a contract with the Spanish government to supply enslaved people to Spanish America.[5] The contract was arranged by two intermediaries named Barry and Black and gave them exclusive access to disembark enslaved people in Cuba and the other Spanish West Indies islands. Barry and Black arranged the on-island functions, such as the holding pens and transportation. In 1786, Baker and Dawson signed a new contract to supply enslaved people taking over these functions themselves. The contract had a fixed price of 155 Pesos for each enslaved person.[6] In total they supplied 11,000 enslaved people that they valued at more than £350,000.[7]

The rulers of the Spanish Caribbean islands became dissatisfied with the sickly nature of Africans and began to return them. Records show Baker and Dawson carried more kidnapped people per ship tonnage than their contemporaries. In 1788, Dawson complained to the UK government about the regulation of the number of the enslaved allowed per ship tonnage.[8] Records do not indicate what happened to those people, most likely they were sold in nearby Jamaica.[8] Even after the Spanish colonies were opened to other slave merchants, Baker and Dawson remained the largest slave trading company in the Spanish Caribbean.[4]

Baker and Dawson had completed over 100 slave voyages by the early 1790s. Dawson, who also slave traded without Baker, went bankrupt in 1793 during a credit crisis.[1]

Personal life

[edit]Baker and Co. shipbuilding company

[edit]Baker was Born in 1732 in Garston, Liverpool. At 13 years old, he was apprenticed to a Joiner for 6 years as was custom at the time, before Baker joined the shipyard of John O'Kill where he worked as a carpenter for 10 years.[9][10] Having become an experienced shipwright and master craftsman, Baker founded his own shipbuilding company "Baker and Co" in 1761 in the vicinity of the Salthouse Dock.[11][10] By 1773, Baker and Co. was given the contract to build the Kent, a 1100-ton burthen ship that, at the time, was the largest to be built in a Liverpool northern dockyard.[9][12] This success drew the British Navy's attention to Baker, who went on to build four naval vessels between 1774-1779 (Penelope, Adamant, Assistance, and Ariel).[9][12][13][14] During this time, Baker's business had also expanded into mercantile trade[a] with West Africa using his own boats.[10][citation needed]

Privateering, the Mentor, and the Carnatic

[edit]

In 1777 Baker and Co. was in a low period, having had few shipbuilding contracts that year and having suffered mercantile losses. A firm had ordered the Privateersman the Mentor of 400-tons. Completed in 1778, the Mentor was refused by the firm who ordered it, dubbing it "cranky and ramshackle,"[15] a dubious claim given Baker's shipbuilding expertise at the time.[16][10] This refusal would have left Baker insolvent, and so a desperate Baker became a privateer using the Mentor himself.[15]

Baker hired John Dawson to captain Mentor, given his privateering success at the time. The Mentor, unaltered and as built, set sail in 1778 bearing 28 guns and 102 men, most of which were the 'scum of the dockland'.[15] When war with France had been announced in April 1778, Baker and Dawson had already sailed south searching for a victim. Before long, a larger vessel appeared on the horizon that seemingly outgunned Mentor. But the crew noticed that many of the gunports were "merely painted dummies."[9][15] So the Mentor attacked and captured the target ship. The ship turned out to be the Carnatic, an east indiaman belonging to the French East India Company. Her cargo included a box of jewels valued at £135,000, as well as gold bullion bringing the total estimate of treasure to between £400,000-500,000. "This was said to be the richest prize ever taken and brought safely into port by a Liverpool privateer".[9][15][17]

Baker and Dawson, merchants and slave traders

[edit]Following the return of Mentor, Baker's financial troubles were resolved, and his business capital greatly expanded. In return, Dawson married Baker's daughter Margaret, formally joining the family and taking on co-ownership of the company which then officially became "Baker and Dawson".[10][17] Prior to Baker venturing out on Mentor, he had leased his shipyard to his then-manager (a man named Barton) for a period of 18 years.[10][citation needed] While the venture was successful, the lease stood, and so Baker lacked a shipyard to continue his shipbuilding enterprise in earnest. As a result, Baker and Dawson focused primarily on the mercantile aspects of the company, massively expanding their involvement in the slave trade,[10] becoming the largest slave trading company in England between the years of 1783-1792.[4] The company itself commissioned ships from Barton including the Princess Royal, Mosley Hill, Brothers, and Young Hero, each of which notorious as slave trading ships during this time.[18][19]

Later life, Carnatic Hall, and shipbuilding legacy

[edit]

In 1779, Baker used his fortune to build the country house Carnatic Hall in Mossley Hill, Liverpool, named after the Carnatic.[9][12] In his later life, Baker became more involved as a politician of the Corporation of Liverpool, the political body of Liverpool prior to its formal status as a city. This political career culminated in Baker's appointment as Mayor of Liverpool in 1795, its chief citizen. Early next year, Baker fell ill, passing on February 7th 1796.[9][12][10][17]

Baker's legacy in Liverpool continued on for generations. When the shipyard lease ran up in 1799, Baker's son-in-law Dawson returned to the shipbuillding business with a partner to form Dawson and Pearson at the north dock site,[20][21] with Dawson being the primary shipbuilder and Pearson taking care of mercantile matters.[10] In 1802, Dawson and Pearson dissolved with Pearson taking any remaining aspects of the slave trading business and Dawson focusing on the shipbuilding aspect as J. Dawson and Co.[10][citation needed] J. Dawson and Co.[22] continued on from 1802-1849, passing to Dawson's grandson (also "John Dawson") in 1819,[citation needed] before closing down permanently with the rise of iron-built steam ships.[10]

The original Carnatic Hall burned down Dec 8th 1889,[10] but was later rebuilt in 1890 with features including two of the original cannons from Mentor on the grounds. This second building was demolished in 1964. The University of Liverpool later purchased the site for a student hall of residence that they named Carnatic Hall, which operated until 2018 when it was closed.[1]

Corporation of Liverpool

[edit]Baker was on the Corporation of Liverpool in 1788. In that year, a House of Commons bill was passed that regulated slave ships. The bill caused a hostile reaction from the Corporation of Liverpool, who petitioned the House of Lords to throw out the bill.[23] Williams writes "The spectacle of the corporation, the members of which must have been perfectly well acquainted with the horrors of the slave trade, appealing to the House of Lords to uphold the infamy of the town, is a melancholy, but striking example of the power of usage and self-interest in blunting the moral vision of men".[23] Liverpool was Britain's pre-eminent slave trading city and twenty-five former mayors of Liverpool were slave traders.[24] Baker himself became Mayor of Liverpool in 1795, a year before he died.[2]

List of vessels owned by Baker and Dawson

[edit]Baker and Dawson were the largest firm of slave traders in England.[4] Vessels they owned included:

Notes

[edit]- ^ while not confirmed in the source text of HS Phillips (1953), this likely already involved the slave trade as many "merchants" of Liverpool did.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Clements, Max (June 21, 2020). "Stark truth that not just city centre benefited from slavery cash". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "Former Mayors and Lord Mayors". Liverpool Town Hall. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Richardson 2007, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d Behrendt, Stephen. "The Captains in the British Slave Trade from 1785 to 1807" (PDF). The Historic site of Lancashire and Cheshire. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Postigo 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Postigo 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Richardson 2007, p. 32.

- ^ a b Postigo 2019, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Griffiths, Robert (1907). History of the Royal and Ancient Toxteth Park. R. Griffiths [1907], Toxteth. ISBN 0902990179.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Phillips (1953), p. 9.

- ^ Shaw, George. "HISTORY OF THE LIVERPOOL DIRECTORIES" (PDF). Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheschire. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d Boult, Joseph (30 April 1868). THE HISTORICAL TOPOGRAPHY OF AIGBURTH AND GARSTON (published 1868). p. 171.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "ADAMANT - British and Irish Shipyards (database)". Shipping and shipbuilding UK. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ "ASSISTANCE - British and Irish Shipyards (database)". Shipping and shipbuilding UK. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Liverpool Echo (July 25, 1961). "Garston Privateer. Liverpool Central Library: archive 920 Bio 2/179". Liverpool Echo.

- ^ "Goree, Liverpool. Part Two: The Goree Piazza". Bygone Liverpool. 4 April 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ a b c Williams 1897, p. 239.

- ^ Lloyd's Register (1783), Seq.no.P534.

- ^ Richardson 2007.

- ^ "Dawson & Pearson 's Yard". threedecks.org. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ "AETNA - Shipping and Shipbuilding UK". Shipping and shipbuilding UK. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ "MANCHESTER - Shipping and shipbuilding UK". Shipping and shipbuilding UK. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ a b Williams 1897, p. 611.

- ^ Long, Chris (January 15, 2020). "The slavers and abolitionists on Liverpool's streets". BBC News. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Morgan, Kenneth (2007). Slavery and the British Empire. Oxford University Press.

- Phillips, Howard Stanley (1953). Three generations of Liverpool shipbuilders, 1761-1871. Unpublished manuscript by a great-great-great-grandson of Peter Baker, 52 pages with added notes. Digital record of permanent collection status at National Museums Liverpool accession: SAS/25A/1/9[1] Digital copy at: File:Item SAS-25A-1-9 - 3 Generations of Old Liverpool Shipbuilders.pdf

- Postigo, José Luis Belmonte (2019). "A Caribbean Affair: The Liberalisation of the Slave Trade in the Spanish Caribbean, 1784-1791". Culture & History Digital Journal. 8 (1): 014. doi:10.3989/chdj.2019.014. hdl:10261/259058.

- Richardson, David (2007). Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery. UK: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-066-9.

- Williams, Gomer (1897). History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque: With an Account of the Liverpool Slave Trade. W. Heinemann.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch