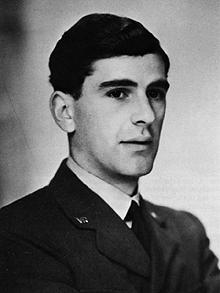

Peter Calvocoressi

Peter John Ambrose Calvocoressi (17 November 1912 – 5 February 2010)[1] was a British lawyer, Liberal politician, historian, and publisher. He served as an intelligence officer at Bletchley Park during World War II.

Early years

[edit]Calvocoressi was born in Karachi, British India (now in Pakistan), to a family of Greek origins from the island of Chios.[2] His mother, Irene (née Ralli), was descended from one of the founders of Ralli Brothers, who were prominent Greek families of Chios who came to London at the time of the Greek Diaspora. When he was three months old, the family moved to Liverpool, England.[1]

Calvocoressi's father Pandia had spent the first seven years of his life in Manchester and the next ten at San Stefano (now Yeşilköy, then in the outskirts of Istanbul). He attended the Sorbonne from the age of 17 for three years and then joined the family firm in New York.[citation needed] Pandia Calvocoressi and Irene Ralli married in London in 1910.[3] Shortly afterwards Pandia was posted to India where Calvocoressi was born. His mother and maternal grandmother were both born in India but spent most of their lives in England.[citation needed]

In 1926, he was elected a scholar of Eton in second place, a position which he retained for the greater part of the next five years. Switching from the standard Classical curriculum to History, he was taught by, among others, the young Robert Birley. At Balliol College, Oxford, in 1931–1934, he was tutored in Modern History mainly by B. H. Sumner and V. H. Galbraith, obtaining a First.[4]

Career

[edit]He was called to the Bar in 1935 and worked in Chancery Chambers until the outbreak of World War II. He spent most of the war as an RAF Intelligence officer at GC&CS Bletchley Park.[5] He worked in 'Hut 3', where decrypted Enigma messages were translated and analysed, and Ultra intelligence was prepared for dispatch to commanders in the field. Calvocoressi rose to be head of the Air Section, which dealt with Luftwaffe intelligence.[6] In summer 1945, he was accredited by British Intelligence to obtain evidence for all four Chief Prosecutors at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.[4] As a member of the British prosecution team, he cross-examined former German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt during the trial. Calvocoressi later advised the US Chief Prosecutor (General Telford Taylor), who had been his Bletchley colleague, in some of the American follow-up trials (1946–1949).[citation needed]

In 1945, he contested the general election, as the Liberal candidate for Nuneaton,[4] finishing third.[citation needed]

From 1950 to 1955, he worked at the Royal Institute for Foreign Affairs (Chatham House), writing five volumes in the series of Annual Surveys of International Affairs, which had previously been written by Arnold Toynbee. From 1955 to 1966, he was a partner in the publishing firms of Chatto and Windus and the Hogarth Press. From 1966 to 1973, he was Reader in International Relations at the University of Sussex, a post which was created for him.[4]

In 1973, he was enticed back to publishing by the offer of the newly created post of Editor-in-Chief of Penguin Books. He was appointed Publisher and Chief Executive of Penguin in the following year. But he fell into disagreements with Penguin's parent company Pearson Longman, and was removed in 1976.[citation needed]

During this period (1955-1976), he was for ten years a part-time member of the United Nations Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, and was Chairman of the Africa Bureau, the London Library, Chios Charities, and Open University Enterprises Ltd. He also served on the governing bodies of Chatham House, the Institute of Strategic Studies, and Amnesty International.[4]

He wrote twenty books, mostly on contemporary history; one of these – World Politics Since 1945 – passed through nine editions. Threading My Way, an autobiography, appeared in 1994. He set private life before and above his career and never had cause to question this priority.[citation needed]

In 1990, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Open University.

Personal life

[edit]In 1938, Calvocoressi married Barbara Eden, daughter of the 6th Baron Henley, with whom he had two sons. After her death in 2005, he married Rachel Scott. They lived in London and Dorset.[7]

Bibliography

[edit]- Nuremberg: The Facts, the Law and the Consequences, 1948

- Survey of International Affairs 1947-1948, 1952

- Survey of International Affairs 1949-1950, 1953

- Survey of International Affairs 1951, 1954

- Survey of International Affairs 1952, 1955

- Survey of International Affairs 1953, 1956

- Middle East Crisis (with Guy Wint), 1957

- South Africa and World Opinion, 1961

- World Order and New States: Problems of Keeping the Peace, 1962

- Suez: Ten Years After (with Anthony Moncrieff), 1967

- World Politics Since 1945, 1968; 2008, 9th ed.

- Total War: Causes and Courses of the Second World War (with Guy Wint and John Pritchard), 1972

- The British Experience 1945-75, 1978

- Freedom to Publish (with Ann Bristow), 1980

- Top Secret Ultra, 1980

- From Byzantium to Eton: A Memoir of a Millennium, 1980

- New Alignments (with Philip Windsor), 1982

- Independent Africa and the World, 1985

- A Time for Peace, 1987

- Who's Who in the Bible, 1987

- Resilient Europe: A Study of the Years 1870-2000, 1991

- The Cold War as Episode, 1993

- Threading My Way, 1994 (autobiography)

- Fall Out: World War II and the Shaping of Postwar Europe, 1997

- The Penguin History of the Second World War, 2 vol., 1999

- World Politics 1945-2000, 2000 (= 8th ed. of World Politics Since 1945)

- Television In College Education, 2005

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- Interview with Peter Calvocoressi by Roger Adelson

References

[edit]- ^ a b Anonymous 2010.

- ^ Calvocoressi 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Family Genealogy Pages: Pantias John (John) Calvocoressi

- ^ a b c d e Irvine & Tusa 2010.

- ^ Calvocoressi 2001.

- ^ Calvocoressi, Peter (1980), Top Secret ULTRA, London: Cassell, ISBN 9780304305469

- ^ "Peter Calvocoressi". The Daily Telegraph. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2024.(subscription required)

Sources

[edit]- Anonymous (5 February 2010), "Obituary: Peter Calvocoressi", Daily Telegraph

- Calvocoressi, Peter (2001), Top Secret Ultra (2nd ed.), Cleobury Mortimer, England: M & M Baldwin, ISBN 978-0947712419

- Irvine, Ian; Tusa, John (8 February 2010), "Obituary: Peter Calvocoressi", The Guardian

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch