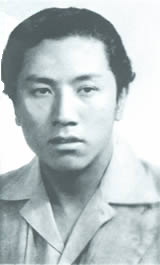

Phuntsok Wangyal

Phuntsok Wangyal Goranangpa | |

|---|---|

| ཕུན་ཚོགས་དབང་རྒྱལ་ 葛然朗巴·平措汪杰 | |

| |

| Leader of the Tibetan Communist Party | |

| In office 1943–1949 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 January 1922 Batang, Kham, Tibet |

| Died | 30 March 2014 (aged 92) Beijing, China |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Political party |

|

Phüntsok Wangyal Goranangpa[a] (2 January 1922 – 30 March 2014), also known as Phüntsog Wangyal,[b] Bapa Phüntsok Wangyal or Phünwang, was a Tibetan politician. A major figure in modern Sino-Tibetan relations, he is best known for being the founder and leader of the Tibetan Communist Party and spending 18 years in the maximum-security prison Qincheng for political prisoners in Beijing in solitary confinement.

Biography

[edit]Phüntsok was born in 1922 in Batang, in the province of Kham in eastern Tibet (in what is now western Sichuan, then under the control of Liu Wenhui, an important Chinese warlord who was affiliated with the Kuomintang).[1] Phüntsok began his political activism at the special academy run by Chiang Kai-shek's Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission in Nanjing, where in 1939 he and a small group of friends secretly founded the Tibetan Communist Party.[2] He was expelled from his school in Nanjing the following year. From 1942 until 1949, he organized a guerilla movement against the Kuomintang, which expanded its military influence in Kham.

The strategy of the Tibetan Communist Party under his leadership during the 1940s was twofold: Influence and gain support for his cause amongst progressive Tibetan students, intellectuals, and members of the powerful aristocracy in Central Tibet in order to establish a program of modernization and democratic (i.e. socialist) reform, and wage a guerilla war against the rule of Liu Wenhui. For some time, Wangyal lectured at Tromzikhang on Barkhor square in the 1940s when it was used as a Republican school.[3]

Phüntsok's political goal was to establish an independent and socialist Tibet through fundamental transformations of Tibet's feudal social structures. Ladakh was part of Phüntsok's vision of a united Tibet.[4] He was exiled by the Tibetan government in 1949, and after joining the Chinese Communist Party's fight against the Kuomintang, he merged the Tibetan Communist Party with the Chinese Communist Party at the behest of the latter's military leaders. As a result of this merger, Phüntsok had to abandon his goals of an independent Tibet.[5]

Phüntsok was present during the negotiations for the Seventeen Point Agreement in May 1951, in which Tibetan leaders saw no viable option than that of capitulating to China's insistence in the preamble that Tibet had formed part of China for over a century. He played an important administrative role in the organization of the Chinese Communist Party in Lhasa and was the official translator of the young 14th Dalai Lama during his famous meetings with Mao Zedong in Beijing in the years 1954 and 1955.[6][7]

In the 1950s, Phüntsok was the highest-ranking Tibetan in the Chinese Communist Party, and although he spoke fluent Chinese, was habituated to Chinese culture and customs and was completely devoted to the cause of socialism and the Chinese Communist Party, his intensive engagement for the well-being of the Tibetans made him suspicious to his powerful party comrades.

Eventually, in 1958, he was placed under house arrest and two years later disappeared from the public eye. During his imprisonment, his wife, a Tibetan Muslim from Lhasa who stayed behind in Beijing with their children, died while she was imprisoned, and all their children were sent to different prisons.

Phüntsok was politically rehabilitated a few years after his release in 1978.[8][9] Later, he was offered the position of Chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region government, which he declined.

A biography of Phüntsok has been published in English, where he particularly emphasises the need to better understand the interests of the Tibetan people in the context of peace and unity within the People's Republic of China.[10]

Later, he declared in an open letter to Hu Jintao that he should accommodate for the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet, suggesting that this gesture would be "... good for stabilizing Tibet." In a third letter dated 1 August 2006, he wrote: "If the inherited problem with Tibet continues to be delayed, it is most likely going to result in the creation of 'The Eastern Vatican of Tibetan Buddhism' alongside the Exile Tibetan Government. Then the 'Tibet Problem', be it nationally or internationally, will become more complicated and more troublesome."[11]

In a letter to Hu Jintao in 2007, Phüntsok criticised cadres of the Chinese Communist Party who, to support Dorje Shugden, "make a living, are promoted and become rich by opposing splittism".[12]

He died on 30 March 2014 at a Beijing hospital.[13]

Published works

[edit]- Liquid water does exist on the moon (1st ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. 2002. ISBN 7-119-01349-1.

- Witness to Tibet's history (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Paljor Publications. 2007. ISBN 978-81-86230-58-9.

- 平等團結路漫漫——對我國民族關係的反思 (in Chinese). Hong Kong: 田園書屋. 2014. ISBN 978-988-15571-9-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (2004). A Tibetan Revolutionary: The political life and times of Bapa Phüntso Wangye. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520249929.

Notes

[edit]- ^

- Standard Tibetan: ཕུན་ཚོགས་དབང་རྒྱལ་

- Chinese: 葛然朗巴·平措汪杰; pinyin: Géránlǎngbā Píngcuòwāngjié

- ^ This is the form given in the Dalai Lama's autobiography Freedom in Exile.

References

[edit]- ^ Tsering Shakya on Melvyn Goldstein et al, A Tibetan Revolutionary. Memoirs of an indigenous Lenin from the Land of Snows, and his long imprisonment by the Mao government.

- ^ Melvin C.Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, William R. Siebenschuh, A Tibetan Revolutionary: The Political Life and Times of Bapa Phüntso Wangye,University of California PressISBN 978-0-520-24992-9 2006 pp.32,123

- ^ Hartley, Lauren R., Schiaffini-Vedani, Patricia (2008). Modern Tibetan literature and social change. Duke University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8223-4277-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gray Tuttle; Kurtis R. Schaeffer (12 March 2013). The Tibetan History Reader. Columbia University Press. pp. 603–. ISBN 978-0-231-14468-1.

- ^ The prisoner by Tsering Shakya

- ^ Goldstein et al.2006 pp.140–153.

- ^ Jonathan Mirsky,'Destroying the Dharma, Times Literary Supplement, 2 December 2004 p.45-47,p.46

- ^ Lectures critiques par Fabienne Jagou

- ^ Le dernier caravanier Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine par Claude Arpi

- ^ Biography of a Tibetan Revolutionary Highlights Complexity of Modern Tibetan Politics

- ^ Baba Phuntsok: Witness to Tibet's History

- ^ Allegiance to the Dalai Lama and those who "become rich by opposing splittism" Archived 25 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tibetan Communist who urged reconciliation with Dalai Lama dies". DNA India. 30 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch