Pokanoket

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| defunct | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Massachusetts, Rhode Island | |

| Languages | |

| Wampanoag | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Wampanoag people |

The Pokanoket (also spelled Pakanokick[1]) are a group of Wampanoag people and the village governed by Massasoit (c. 1581–1661), chief sachem of the Wampanoag people.

The village was located on what is now called Mount Hope in Bristol, Rhode Island. Later the term Pokanoket broadened to refer to the peoples and lands governed by Massasoit and his successors,[1] which were part of the Wampanoag people in what is now Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

Name

[edit]Pokanoket is also spelled Pauquunaukit, and translates as "land at the clearing" from the Massachusett.[citation needed]

History

[edit]At the time of the pilgrims' arrival in Plymouth, the realm of Pokanoket included parts of Rhode Island and much of southeastern Massachusetts.[2] European accounts of Pokanoket social life noted the political authority of the Massasoit (Great Leader).

The realm of the Pokanoket was extensive and known to the Pilgrims before they arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts on the Mayflower in 1620. William Bradford wrote that he had received before the Pilgrims sailed: "The Pokanokets, which live to the west of Plymouth, bear an inveterate malice to the English, and are of more strength than all the savages from there to Penobscot. Their desire of revenge was occasioned by an English man who, having many of them on board, made a great slaughter with their murderers and small shot, when (as they say) they offered no injury on their part."

The area in Rhode Island consisting of Bristol, Barrington, and Warren (the latter named Sowams by the natives) was the main settlement of the Pokanoket when the Pilgrims arrived. Bradford had been told that the land of the Pokanoket had "the richest soil, and much open ground fit for English grain".[3]

Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed into Narragansett Bay in 1524, and people appeared on the shores, most likely Pokanokets. The navigator's recorded latitude of 41°40′ north corresponds to Mount Hope Bay, where the seat of the Pokanoket is located. Verrazzano wrote of these Rhode Island Native Americans whom he encountered: "These people are the most beautiful and have the most civil customs we have found on this voyage."[4][5]

The Pilgrims lost more than half of their people due to sickness and starvation over the first winter. The Pokanoket taught them how to plant crops and live in this country. Despite the fears initially felt by the Pilgrims, the Pokanoket quickly made a pact of peace with the new settlers. Bradford referred to the Pokanoket leader Ousamequin as "their great Sachem, called Massasoit". Ousamequin was succeeded as Great Leader of the Pokanoket by his sons, first by Wamsutta, (also known as Alexander), and then by Metacomet (also known as Philip), who was killed in the King Philip's War (1675–76).

Natick, sometimes referred to as Pokanoket, is the dialect of Massachusett spoken among the Pokanoket.[6]

List of Pokanoket leaders

[edit]| Sachem | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Massasoit Wasanegin | 1525 | 1577 |

| Massasoit Ousamequin | 1581 | 1661 |

| Massasoit Wamsutta (English name "Alexander") | 1661 | 1662 |

| Massasoit Metacomet (English name "Philip") | 1662 | 1676 |

Historical territories

[edit]

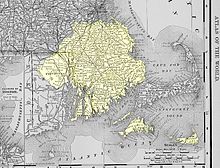

The Pokanoket's conceded territory shown in the map featured here is a reconstruction of Pokanoket ancestral boundaries based on a political and topographical map from 1895, which itself drew on 17th-century topographical descriptions of political borders.

Today, the area includes cities and towns on the Massachusetts and Rhode Island border such as Bristol, Warren, Barrington, East Providence, Seekonk, Rehoboth, Attleboro, Cumberland, North Attleboro, Norton, Mansfield, Dighton, and Somerset.

Map points

[edit]- Both the Seller Map and the Hack Map document Pokanoket ancestral land to the east and west of the head of what is now called Narragansett Bay.

- Pokanoket used rivers as boundaries for their ancestral lands due to the natural geographical features of their area. On the west side of the bay, the boundary starts in the land that is called Cowessett ( Cowee means pines. Cowessett Place of Pines ) (Land at the border). The Pawtuxet River is the natural boundary that defines the border between the Narragansett and Pokanoket Tribes. Narragansett lands are to the south of the Pawtuxet River.

- Pokanoket lands lie to the north and northeast of the Pawtuxet River as far north as the Ponegunsett Reservoir, then continue northeast of the Ponegunsett Reservoir, northward up the Chepachet River.

- The Nipmuc lands are west and northwest of the Chepachet River. East of this river is Pokanoket lands.

- We now follow the Charles River from its basin northeasterly until it empties into Boston Bay. The lands to the west of the Charles River are Nipmuc lands. The lands to the east are Pokanoket lands.

- The lands north of the Charles River are Massachusetts lands and the lands south of the Charles River are Pokanoket lands.

- The eastern mainland boundary of Pokanoket is located at what is now the Cape Cod Canal, which was once a tributary extended from Great Herring Pond. West of this border is Pokanoket land. East of this natural border is the land of the Nausett.

- This leaves the islands in what we now call Narragansett Bay and the islands off the coast. All the islands in Narragansett Bay on this map are highlighted except for Jamestown and Dutch Island. These two islands belong to the Narragansett, as well as Block Island located in Rhode Island Sound.

Descendants

[edit]Today, descendants from the Pokanoket village are part of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, a federally recognized tribe in Massachusetts.[7]

An unrecognized tribe, the Pokanoket Tribe, also known as the Pokanoket Nation claims to descend from the Pokanoket people.[7] They are not federally recognized;[8] state-recognized by Rhode Island, Massachusetts, or any other state;[9] or recognized by Wampanoag tribes.[10] The town of Warren, Rhode Island, lists a land acknowledgment on a town sign.[11]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Kathleen J. Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650, page 21

- ^ Wright, Otis Olney, ed. (1917). History of Swansea, Massachusetts, 1667–1917. Town of Swansea. p. 19. OCLC 1018149266. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ William Wallace Tooker, review of Virginia Baker's "Massasoit's Town Sowams in Pokanoket: Its History, Legends, and Traditions" (1894) in American Anthropologist, Vol. 6, No. 4, July–September 1904, pp. 547-548 (JSTOR 659287); and William Bradford, Of Plimouth Plantation, Book 2.

- ^ Brasser, T. J. (1978). "Early Indian-European Contacts", in Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant, Washington: Smithsonian Institution, V. 15, p. 80.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1971). The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages: A.D. 500-1600, p. 307.

- ^ Moseley, Christopher and R. E. Asher, ed. Atlas of the World's Languages (New York: Routledge, 1994) Map 3.

- ^ a b Lindahl, Chris (May 13, 2017). "R.I. tribe protests repatriation ceremony". Cape Cod Times. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Indian Affairs Bureau (January 29, 2021). "Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register. 85 FR 5462: 7554–58. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "State Recognized Tribes". National Conference of State Legislatures. 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "The Pokanoket Encampment", Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative, Brown University, August 24, 2017

- ^ Farzan, Antonia Noori. "3 Rhode Island towns adopt 'land acknowledgements' honoring Native American tribes". The Providence Journal. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

References

[edit]- Bragdon, Kathleen J. (1999). Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-806131269.

- Gookin, Daniel (1970). Historical Collections of the Indians in New England, with notes by Jeffrey H. Fiske, published by Towtaid, pg. 10

- Salwen, Bert (1978). "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island: Early Period", in Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant, Washington: Smithsonian Institution, V. 15, p. 171.

- Seller, John (1675). Maps of Early Massachusetts, compiled, ed. and published by Lincoln A. Dexter, pp. 78–79.

External links

[edit]- Pokanoket, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center

- Philip of Pokanoket: An Indian Memoir, by Washington Irving

- Mount Hope, Sacred Land of the Pokanokets

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch