Psychological behaviorism

Psychological behaviorism is a form of behaviorism—a major theory within psychology which holds that generally human behaviors are learned—proposed by Arthur W. Staats. The theory is constructed to advance from basic animal learning principles to deal with all types of human behavior, including personality, culture, and human evolution. Behaviorism was first developed by John B. Watson (1912), who coined the term "behaviorism", and then B. F. Skinner who developed what is known as "radical behaviorism". Watson and Skinner rejected the idea that psychological data could be obtained through introspection or by an attempt to describe consciousness; all psychological data, in their view, was to be derived from the observation of outward behavior. The strategy of these behaviorists was that the animal learning principles should then be used to explain human behavior. Thus, their behaviorisms were based upon research with animals.

Staats' program takes the animal learning principles, in the form in which he presents them, to be basic. But, also on the basis of his study of human behaviors, adds human learning principles. These principles are unique, not evident in any other species.[1] Holth also critically reviews psychological behaviorism as a "path to the grand reunification of psychology and behavior analysis".[2]

Basic principles

[edit]The preceding behaviorisms of Ivan P. Pavlov, Edward L. Thorndike, John B. Watson, B. F. Skinner, and Clark L. Hull studied the basic principles of conditioning with animals. These behaviorists were animal researchers. Their basic approach was that those basic animal principles were to be applied to the explanation of human behavior. They did not have programs for the study of human behavior broadly, and deeply.

Staats was the first to do his research with human subjects. His study ranged from research on basic principles to research and theory analysis of a wide variety of human behaviors, real life human behaviors. That is why Warren Tryon (2004) suggested that Staats change the name of his approach to psychological behaviorism, because Staats behaviorism is based upon human research and unifies aspects of traditional study with his behaviorism.

That includes his study of the basic principles. For example, the original behaviorists treated the two types of conditioning in different ways. The most generally used way by B. F. Skinner constructively considered classical conditioning and operant conditioning to be separate and independent principles. In classical conditioning, if a piece of food is provided to a dog shortly after a buzzer is sounded, for a number of times, the buzzer will come to elicit salivation, part of an emotional response. In operant conditioning, if a piece of food is presented to a dog after the dog makes a particular motor response, the dog will come to make that motor response more frequently.

For Staats, these two types of conditioning are not separate, they interact. A piece of food elicits an emotional response. A piece of food presented after the dog has made a motor response will have the effect of strengthening that motor response so that it occurs more frequently in the future.

Staats sees the piece of food to have two functions: one function is that of eliciting an emotional response, the other function is that of strengthening the motor behavior the precedes the presenting of food. So classical conditioning and operant conditioning are very much related.

Positive emotion stimuli will serve as positive reinforcers. Negative emotion stimuli will serve as punishers. As a consequence of humans' inevitable learning positive emotion stimuli will serve as positive discriminative stimuli, incentives. Negative emotion stimuli will serve as negative discriminative stimuli, disincentives. Therefore, emotion stimuli also have reinforcing value and discriminative stimulus value. Unlike Skinner's basic principles, emotion and classical conditioning are central causes of behavior.

Principles of human learning

[edit]Unlike the other behaviorisms, Staats' considers human learning principles. He states that humans learn complex repertoires of behavior like language, values, and athletic skills—that is cognitive, emotional, and sensory motor repertoires. When such a repertoire has been learned, they change the individual's learning ability. A child who has learned language, a basic repertoire, can learn to read. A person who has learned a value system, such as a system of beliefs in human freedom, can learn to value different forms of government. An individual who has learned to be a track athlete, can learn to move more quickly as a football player. This introduces a basic principle of psychological behaviorism, that human behavior is learned cumulatively. Learning one repertoire enables the individual to learn other repertoires that enable the individual to learn additional repertoires, and on and on. Cumulative learning is a unique human characteristic. It has taken humans from chipping hand axes to flying to the moon, learned repertoires that enable the learning of new repertoires that enable the learning of new repertoires in an endless fashion of achievement.

That theory development enables psychological behaviorism to deal with types of human behavior. Out of the reach of radical behaviorism, for example, personality.

Foundations of personality theory

[edit]| The personality theory of psychological behaviorism | |

| |

| Preceding behaviorists Author Major works | |

| Psychology portal | |

Description

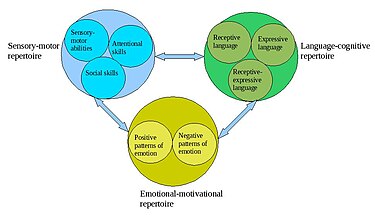

[edit]Staats proposes that radical behaviorism is insufficient, because in his view psychology needs to unify traditional knowledge of human behavior with behaviorism. He has called that behaviorizing psychology in a way that enables psychological behaviorism to deal with topics not usually dealt with in behaviorism, such as personality.[9] According to this theory, personality consists of three huge and complex behavioral repertoires:[1]

- sensory-motor repertoire, including basic sensory-motor abilities, as well as attentional and social skills;

- language-cognitive repertoire, including receptive language, expressive language, and receptive-expressive language;

- emotional-motivational repertoire, including positive and negative patterns of emotional reaction directing the whole behavior of the person.

The infant begins life without the basic behavioral repertoires. They are acquired through complex learning, and as this occurs, the child becomes able to respond appropriately to various situations.[2]

Whereas at the beginning learning involves only basic conditioning, as repertories are acquired the child's learning improves, being aided by the repertoires that are already functional. The way a person experiences the world depends on his/her repertoires. The individual's environment to the present results in learning a basic behavioral repertoire (BBR). The individual's behavior is function of the life situation and the individual's BBR. The BBRs are both a dependent and an independent variable, as they result from learning and cause behavior, constituting the individual's personality. According to this theory, biological conditions of learning are essential. Biology provides the mechanisms for learning and performance of behavior. For example, a severely brain-damaged child will not learn BBRs in a normal manner.

According to Staats, the biological organism is the mechanism by which the environment produces learning that results in basic behavioral repertoires which constitute personality. In turn, these repertoires, once acquired, are modifying the brain's biology, through the creation of new neural connections. Organic conditions affect behavior through affecting learning, basic repertoires, and sensory processes. The effect of environment on behavior can be proximal, here-and-now, or distal, through memory and personality.[2] Thus, biology provides the mechanism, learning and environment provide the content of behavior and personality. Creative behavior is explained by novel combinations of behaviors elicited by new, complex environmental situations. The self is the individual's perception of his/her behavior, situation, and organism. Personality, situation, and the interaction between them are the three main forces explaining behavior. The world acts upon the person, but the person also acts both on the world, and on him/herself.

Methods

[edit]The methodology of psychological behavioral theory contains techniques of assessment and therapy specially designed for the three behavioral repertoires:

- classical sensorimotor techniques;

- language-cognitive techniques (verbal association, verbal imitation, and verbal-writing);

- emotional-motivational techniques (the time-out technique).[1]

Paradigm

[edit]Psychology and behaviorism

[edit]Watson named the approach behaviorism as a form of revolution against the then prevalent use of introspection to study the mind. Introspection was subjective and variable, not a source of objective evidence, and the mind consisted of an inferred entity that could never be observed. He insisted psychology had to be based on objective observation of behavior and the objective observation of the environmental events that cause behavior. Skinner's radical behaviorism also has not established a systematic relationship to traditional psychology knowledge.

Psychological behaviorism—while bolstering Watson's rejection of inferring the existence of internal entities such as mind, personality, maturation stages, and free will—considers important knowledge produced by non-behavioral psychology that can be objectified by analysis in learning-behavioral terms. As one example, the concept of intelligence is inferred, not observed, and thus intelligence and intelligence tests are not considered systematically in behaviorism. However, PB considers IQ tests measure important behaviors that predict later school performance and intelligence is composed of learned repertoires of such behaviors. Joining the knowledge of behaviorism and intelligence testing yields concepts and research concerning what intelligence is behaviorally, what causes intelligence, as well as how intelligence can be increased.[10] It is thus a behaviorism that systematically incorporates and explains, behaviorally, empirical parts of psychology.

Basic principles

[edit]The different behaviourisms also differ with respect to basic principles. Skinner contributed greatly in separating Pavlov's classical conditioning of emotion responses and operant conditioning of motor behaviors. Staats, however, notes that food was used by Pavlov to elicit a positive emotional response in his classical conditioning and Thorndike Edward Thorndike used food as the reward (reinforcer) that strengthened a motor response in what came to be called operant conditioning, thus emotion-eliciting stimuli are also reinforcing stimuli.[6] Watson, although the father of behaviorism, did not develop and research a basic theory of the principles of conditioning. The behaviorists whose work centered on that development treated differently the relationship of the two types of conditioning. Skinner's basic theory was advanced in recognizing two different types of conditioning, but he didn't recognize their interrelatedness, or the importance of classical conditioning, both very central for explaining human behavior and human nature.

Staats' basic theory specifies the two types of conditioning and the principles of their relationship. Since Pavlov used a food stimulus to elicit an emotional response and Thorndike used food as a reward (reinforcer) to strengthen a particular motor response, whenever food is used both types of conditioning thus take place.[11] That means that food both elicits a positive emotion and food will serve as a positive reinforcer (reward). It also means that any stimulus that is paired with food will come to have those two functions. Psychological behaviorism and Skinner's behaviorism both consider operant conditioning a central explanation of human behavior, but PB additionally concerns emotion and classical conditioning.

Language

[edit]This difference between the two behaviorisms can be seen clearly in their theories of language. Staats, extending prior theory[12][13] indicates that a large number of words elicit either a positive or negative emotional response because of prior classical conditioning. As such they should transfer their emotional response to anything with which they are paired. PB provides evidence this is the case.[14] PB's basic learning theory also states that emotional words have two additional functions. They will serve as rewards and punishments in learning other behaviors,[15] and they also serve to elicit either approach or avoidance behavior.[16] Thus, (1) hearing that people of an ethnic group are dishonest will condition a negative emotion to the name of that group as well as to members of that group, (2) complimenting (saying positive emotional words to) a person for a performance will increase the likelihood the person will perform that action later on, and (3) seeing the sign RESTAURANT will elicit a positive emotion in a hungry driver and thus instigate turning into the restaurant's parking lot. Each case depends upon words eliciting an emotional response.

PB treats various aspects of language, from its original development in children to its role in intelligence and in abnormal behavior,[4][8][17] and backs this up with basic and applied study. His theory paper in the journal Behavior Therapy[18] helped introduce cognitive (language) behavior therapy to the behavioral field.

Child development

[edit]Much of the research on which PB is based has concerned children's learning. For example, there is a series of studies of the first learning of reading with preschoolers[19][20][21] and also a series studying and training dyslexic adolescent children.[22][23][24] The psychological behaviorism (PB) position became that the norms of child development—the ages when important behaviors appear—are due to learning, not biological maturation.

Staats began studies to analyze cases of important human behaviors in basic and applied ways in 1954. In 1958 he analyzed dyslexia and introduced his token reinforcer system (later called the token economy) along with his teaching method and materials for treating the disorder. When his daughter Jenny was born in 1960 he began to study and to produce her language, emotional, and sensory-motor development. When she was a year and a half old he began teaching her number concepts, and then reading six months later, using his token reinforcer system, as he recorded on audiotape. Films were made in 1966 of Staats being interviewed about his conception of how variations in children's home learning variously prepared them for school on the first of three Arthur Staats YouTube videos.[25] Following that the second Staats YouTube video[26] records him beginning teaching his three-year-old son with the reading learning (and counting) method he developed in 1962 with his daughter. This film also shows a graduate assistant working with a culturally deprived four-year-old learning reading and writing numbers and counting, participating voluntarily. The Staats YouTube video number 3[27] has additional cases of these usually delayed children voluntarily learning much ahead of time these cognitive repertoires that prepare them for school. This group of 11 children gained an average of 11 points in IQ and advanced significantly on a child development measure as they also learned to like the learning situation. Staats published the first study in this series in 1962 and describes his later studies and his more general conception in his 1963 book. This research, that included work with his own children from birth on, was the basis for Staats' books[1][5][6][8] specifying the importance of the parents' early training of the child in language and other cognitive repertoires. He shows they are the foundations for being intelligent and doing well on entering school. There are new studies showing that parents who talk to their children more have children with advanced language development, school success, and intelligence measures. These statistical studies should be joined with Staats' work with individual children that shows the specifics of the learning involved and how to best produce it. The two together show powerfully the importance of early child learning.

Staats also applied his approach in fathering his own children and employed his findings in constructing conception of human behavior and human nature.[4][8][17] He deals with many aspects of child development, from babbling to walking to discipline and time-out, and he considers parents one of his audiences.[5] In the last of his books he summarizes his theory of child development. His position is that children are the young of the human species that has a body that can make an infinity of different behaviors. The human species also has a nervous system and brain of 100 billion neurons that can learn in marvelous complexity. The child's development consists of the learning of repertoires, extraordinarily complex, like a language-cognitive repertoire, an emotional-motivational repertoire, and a sensory-motor repertoire, each including sub-repertoires of various kinds. The child's behavior, in the various life situations encountered, depend upon the repertoires that have been learned. The child's ability to learn in the variety of situations encountered also depends on the repertoires that have been learned. This conception makes parenting central in the child's development, supported by many studies in behavior analysis, and offers knowledge to parents in raising their children.

Personality

[edit]Staats[8] describes humans great variability in behavior, across different people. Those individual differences are consistent in different life situations and typify people. Those differences also tend to run in families. Such phenomena have led to the concept of personality as some internal trait that is inherited that strongly determines individuals' characteristic ways of behaving. Personality conceived in that way remains an inference, based on how people behave, but with no evidence of what personality is.

More successful has been the measurement of personality. There are tests of intelligence for example. No internal organ of intelligence has been found, and no genes either, but intelligence tests have been constructed that predict (helpfully but not perfectly) the performance of children in school. Children who have the behaviors measured on the tests display better learning behaviors in the classroom. Although such tests have been widely applied radical behaviorism has not invested in the study of personality or personality testing.

Psychological behaviorism (e.g.[8]) however considers it important to study what personality is, how personality determines behavior, what causes personality, as well as what personality tests measure. Tests (including intelligence tests) are considered to measure different repertoires of behavior that individuals have learned. The individual in life situations also displays behaviors that have been learned. That is why personality tests can predict how people will behave. That means also that tests can be used to identify important human behaviors, and the learning that produces those behaviors can be studied. Gaining that knowledge will make it possible to develop environmental experiences that produce or prevent types of personality from developing. A study has shown,[28] for example, that in learning to write letters of the alphabet children learn repertoires that make them more intelligent.

Abnormal personality

[edit]Psychological behaviorism's theory of abnormal personality rejects the concept of mental illness. Rather behavior disorders are composed of learned repertoires of abnormal behavior. Behavior disorders also involve not having learned basic repertoires that are needed in adjusting to life's demands. Severe autism can involve not having learned a language repertoire as well as having learned tantrums and other abnormal repertoires.[29]

PB's theories of various behavior disorders[8] employ the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders[30] (DSM) descriptions of both abnormal repertoires and the absence of normal repertoires. Psychological behaviorism provides the framework for an approach to clinical treatment of behavior disorders, as shown in the field of behavior analysis.[8][28][31][32][33] PB theory also indicates how behavior disorders can be prevented by preventing the abnormal learning conditions that produce them.

Education

[edit]The PB theory is that child development, besides its physical growth, consists of the learning of repertoires some of which are basic in the sense they provide the behaviors for many life situations and also they determine what and how well the individual can learn. That theory states that humans are unique in having a building type of learning, cumulative learning, in which basic repertoires enable the child to learn other repertoires that enable the learning of other repertoires. Learning language, for example, enables the child to learn various other repertoires, like reading, number concepts, and grammar. Those repertoires provide the bases for learning other repertoires. For example, reading ability, opens the possibilities for an individual to do things and learn things that a non-reader cannot.

With that theory, and with its empirical methodology, PB applies to education. For example, it has a theory of reading that explains children's differences, from dyslexia to advanced reading ability.[33] PB also suggests how to treat dyslexic children and those with other learning disabilities. Psychological behaviorism's approach has been supported and advanced in the field of behavior analysis.[8][34][35]

Human evolution

[edit]Human origin is generally explained by Darwin's natural selection;[36][37][38][39][40] However, while Darwin gathered imposing evidence showing the evolution of physical characteristics of species his view that behavioral characteristics (such as human intelligence) also evolved was pure assumption with no evidentiary support PB presents a different theory, that the cumulative learning of pre-human hominins drove human evolution. That explains the consistent increase in brain size over the course of human evolution. That occurred because the members of the evolving hominin species were continually learning new language, emotion-motivation, and sensory-motor repertoires. That meant the new generations had to learn those ever more complex repertoires. It was cumulative learning that consistently created the selection device for the members of those generations that had the larger brains and were the better learners.

That theory makes learning ability central in human origin, selecting who would survive and reproduce, until the advent of Homo sapiens where all individuals (except if damaged) have full brains and full learning ability.[8]

Theory levels

[edit]Psychological behaviorism is set forth as an overarching theory, constructed of multiple theories in various areas. Staats considers it a unified theory. The areas are related, their principles consistent, and they are advanced consistently, composing levels from basic to increasingly advanced. Its most basic level calls for a systematic study of the biology of the learning "organs" and their evolutionary development, from species like amoeba that have no learning ability to humans that have the most. The basic learning principles constitute another level of theory, as do the human learning principles that specify cumulative learning. How the principles work—in areas like child development, personality, abnormal personality, clinical treatment, education, and human evolution—compose additional levels of study.[8][33] Staats sees the overarching theory of PB as basic for additional levels that compose the social sciences of sociology, linguistics, political science, anthrology, and paleoanthropology. He criticizes the disunification of the sciences that study human behavior and human nature. Because they are disconnected, they do not build a related, simpler and more understandable conception and scientific endeavor as, for example, the biological sciences do.[7] This philosophy of science of unification is at one with Staats' attempt to construct his unified psychological behaviorism.

Projections

[edit]Psychological behaviorism's works project new basic and applied science at its various theory levels. The basic principles level, as one example, needs to study systematically the relationship of the classical conditioning of emotional responses and the operant conditioning of motor responses. As another projection, the field of child development should focus on the study of the learning of the basic repertoires. One essential is the systematic detailed study of the learning experiences of children in the home from birth on. He says such research could be accomplished by installing cameras in the homes of volunteering, remunerated families. This research should also be done to discover how such learning produces both normal and abnormal personality development. As another example, PB also calls for educational research into how school learning could be advanced using its methods and theories. Also, Staats' theory of human evolution is seen to call for research and theory developments.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Staats, Arthur W (1996), Behavior and personality: psychological behaviorism, New York: Springer, ISBN 978-0826193117

- ^ a b c Holth, P (2003). "Psychological Behaviorism: A Path to the Grand Reunification of Psychology and Behavior Analysis?". The Behavior Analyst Today. 4 (3): 306–309. doi:10.1037/h0100019.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W. (with contributions from Carolyn K. Staats) (1963). Complex Human Behavior a Systematic Extension of Learning Principles. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-1258220624.

- ^ a b c Staats, Arthur W. (1968a). Learning, Language, and Cognition. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 978-0039100513.

- ^ a b c Staats, Arthur W. (1971). Child learning, intelligence, and personality. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0914474289.

Arthur W. Staats.

- ^ a b c Staats, Arthur W. (1975). Social Behaviorism. Homewood, IL: Dorsey. p. 655. ISBN 978-0256015379.

- ^ a b Staats, (1983) Psychology's Crisis of Disunity. New York: Praeger

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Staats, Arthur W. (2012). The Marvelous Learning Animal : what makes human nature unique. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1616145972.

- ^ "Behaviorism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Burns, G. Leonard (1982). "Emotional personality repertoire as cause of behavior: Specification of personality and interaction principles". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 43 (4): 873–881. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.4.873.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W. (2006). "Positive and Negative Reinforcer: How About the Second and Third Functions?". Behavior Analyst. 29 (2): 271–272. doi:10.1007/BF03392136. PMC 2223154. PMID 22478469.

- ^ Mowrer, Orval (1954). "The psychologist looks at language". American Psychologist. 9 (11): 660–694. doi:10.1037/h0062737.

The Psychologist Looks at Language

- ^ Osgood, Charles E. (1953). Method and theory in experimental psychology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195010084.

- ^ Staats, Arthur; Saats, Carolyn (1959). "Attitudes established by classical conditioning". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 57 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1037/h0042782. PMID 13563044.

- ^ Finley, Judson R.; Staats, Arthur W. (1967). "Evaluative meaning words as reinforcing stimuli". Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 6 (2): 193–197. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(67)80094-X.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Warren, Don R. (1974). "Motivation and the three-function learning: Food deprivation and approach-avoidance to food words". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 103 (6): 1191–1199. doi:10.1037/h0037417.

- ^ a b Staats, Arthur W. (1968b). Social behaviorism and human motivation: Principles of the attitude-reinforcer-discriminative system. In Greenwald, Anthony G.; Brock, Timothy C.; Ostrom, Timothy M. (Eds.), Psychological foundations of attitudes. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0805804072

- ^ Staats, Arthur W (1972). "Language behavior therapy: A derivative of social behaviorism". Behavior Therapy. 3 (2): 165–192. doi:10.1016/s0005-7894(72)80079-0.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Brewer, Barbara A.; Gross, Michael C. (1970). "Learning and cognitive development: Representative samples, cumulative-hierarchical learning, and experimental-longitudinal learning. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 35(8, Whole No. 141).

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Staats, Carolyn K.; Schutz, Richard E.; Wolf, Montrose M. (1962). "The conditioning of textual responses using "extrinsic" reinforcers". Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 5 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1901/jeab.1962.5-33. PMC 1404175. PMID 13916029.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Minke, Karl A.; Finley, Jud R.; Wolf, Montrose M.; Brooks, Lloyd O. (1964). "A reinforcer system and experimental procedure for the laboratory study of reading". Child Development. 35 (1): 209–231. doi:10.2307/1126585. JSTOR 1126585.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Butterfield, William H. (1965). "Treatment of Nonreading in a Culturally Deprived Juvenile Delinquent: An Application of Reinforcement Principles". Child Development. 36 (4): 925–942. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1965.tb05349.x. PMID 5851039.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Minke, Karl A.; Butts, Priscilla (1970). "A token-reinforcement remedial reading program administered by black therapy-technicians to problem black children". Behavior Therapy. 1 (3): 331–353. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(70)80112-5.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W.; Minke, Karl A.; Goodwin, William; Landeen, Julie (1967). "Cognitive behavior modification: 'Motivated learning' reading treatment with subprofessional therapy-technicians". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 5 (4): 283–299. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(67)90020-4.

- ^ "Psychological Behaviorism Part 1". YouTube.

- ^ "Psychological Behaviorism Part 2". YouTube.

- ^ "Psychological Behaviorism Part 3". YouTube.

- ^ a b Staats, Arthur W.; Burns, G. Leonard (1981). "Intelligence and child development: What intelligence is and how it is learned and functions". Genetic Psychology Monographs. 104: 237–301.

- ^ Arthur W. Staats (1996). Behavior and Personality: Psychological Behaviorism. New York: Springer.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2000). DSM-IV-TR : diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4TH ed.). United States: AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC PRESS INC (DC). ISBN 978-0890420256.

- ^ Staats, Arthur W. (2003). "A psychological behaviorism theory of personality." In Millon, Theodore; Learner, Melvin J. (Eds.), Handbook of psychology [italics here]. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-38404-6 pp 135-158.

- ^ Staats, A. W. (1957). "Learning theory and "opposite speech". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 55 (2): 268–269. doi:10.1037/h0043902. PMID 13474899.

- ^ a b c Staats, (1975) Social Behaviorism. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press. ISBN 0256015376

- ^ Staats, Arthur W. (1973). Behavior analysis and token reinforcement in educational behavior modification and curriculum research. Behavior modification in education: 72nd yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press ISBN 0030632897

- ^ Sulzer-Azeroff, B., & Mayer, G.R. (1986). Advancing educational excellence and behavioral strategies. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston ISBN 0030716519

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1992). The third chimpanzee. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060845503

- ^ Ehlich, Paul (2000). Human Natures. Washington, D.C.: Island Press/Shearwater Books ISBN 0142000531

- ^ Gould, Stephen J. (1996) Dinosaur in a haystack. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-517-88824-7

- ^ Johanson, Donald & Edgar, Blake (1996). From Lucy to language. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0684810239

- ^ Tattersall, Ian, Schwartz, Jeffrey H. (2000). Extinct humans. New York: Westview Press.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch