Public opinion on climate change

Public opinion on climate change is related to a broad set of variables, including the effects of sociodemographic, political, cultural, economic, and environmental factors[3] as well as media coverage[4] and interaction with different news and social media.[5] International public opinion on climate change shows a majority viewing the crisis as an emergency.

Public opinion polling is an important part of studying climate communication and how to improve climate action. Evidence of public opinion can help increase commitment to act by decision makers.[6] Surveys and polling to assess opinion have been done since the 1980s, first focusing on awareness, but gradually including greater detail about commitments to climate action. More recently, global surveys give much finer data, for example, in January 2021, the United Nations Development Programme published the results of The Peoples' Climate Vote. This was the largest-ever climate survey, with responses from 1.2 million people in 50 countries, which indicated that 64% of respondents considered climate change to be an emergency, with forest and land conservation being the most popular solutions.[7]

Public surveys

[edit]

According to a 2015 journal article based on a literature review of thousands of articles related to over two hundred studies covering the period from 1980 to 2014, there was an increase in public awareness of climate change in the 1980s and early 1990s, followed by a period of growing concern— mixed with the rise of conflicting positions—in the later 1990s and early 2000s. This was followed by a period of "declining public concern and increasing skepticism" in some countries in the mid-2000s to late-2000s. From 2010 to 2014, there was a period suggesting "possible stabilization of public concern about climate change".[14]

The 2021 Lloyd's Register Foundation World Risk Poll conducted by Gallup found that 67% of people viewed climate change as a threat to people in their country, which is a slight decrease from 69% in 2019, possibly due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on health and livelihoods being pressing issues.[15][16] The 2021 poll was conducted in 121 countries and included over 125,000 interviews. The study also revealed that many countries and regions with high experience of disasters related to natural hazards, including those made more frequent and severe by climate change, are also those with low resilience.[17]

A 2021 survey conducted by the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) found that 75% of young British (16-24) respondents agreed with the view that climate change was a specifically capitalist problem.[18]

Over 73,000 people speaking 87 different languages across 77 countries were asked 15 questions on climate change for the Peoples' Climate Vote 2024, a public opinion survey on climate change, which was conducted for the UN Development Programme (UNDP) with the University of Oxford and GeoPoll. It showed 80 percent people globally want their governments to take stronger action to tackle the climate crisis.[19]

In 2024 Ipsos conducted a survey about the importance of climate issues in elections. It found that among the factors influencing the voters' decisions, climate change is generally at the 10th place of importance, long behind other issues, especially inflation. This worried some experts as around 4 billion people from more than 65 countries, responsible for 40% of emissions, are expected to participate in national elections in 2024.[20]

Results from climate survey of European Investment Bank in 2021

[edit]91% of Chinese respondents to an EU survey in 2021, 73% of Britons, 70% of Europeans and 60% of Americans support stronger policies for climate change mitigation. 63% of EU residents, 59% of Britons, 50% of Americans and 60% of Chinese respondents are in favor of switching to renewable energy. 18% of Americans are in favor of natural gas as a source of energy. For Britons and EU citizens, nuclear energy is a more popular energy alternative.[21] 69% of EU respondents, 71% of UK respondents, 62% of US respondents and 89% of Chinese respondents support a tax on the items and services that contribute the most to global warming.[21]

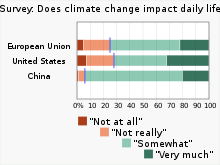

In the 2022 edition of the same climate survey, in the European Union and the United Kingdom 87% of respondents agree that their government has moved too slowly to address climate change, compared to 76% and 74%, respectively, in China and the United States.[22][23] The majority of persons polled in the European Union and China (80% and 91%, respectively) think that climate change has an impact on their daily life. Meanwhile, Americans (67%) and Britons (65%) have a less extreme picture of this.[22][24][25] More findings from the survey show that 63% of people in the European Union want energy costs to be dependent on use, with the greatest consumers paying more. This is compared to 83% in China, 63% in the UK and 57% in the US.[22][26]

Compared to 84% in China, 66% in the United States, and 52% in the United Kingdom, 64% of EU respondents want polluting activities like air travel and SUVs to be taxed more heavily to account for their environmental impact.[22][27][28] 88% of Chinese, 83% of British, and 72% of American respondents, 84% of EU respondents believe that a worldwide catastrophe is inevitable if the consumption of products and energy is not lowered in the next years.[22][24][29]

According to the European Investment Bank's climate survey from 2022, 84% of EU respondents stated that if we do not significantly cut back on our consumption of goods and energy in the near future, the negative effects would be non-reversible. 63% of EU citizens want energy prices to be based on consumption, with higher costs for those individuals or businesses who use the most energy and 40% of respondents from the EU believe that their government should lower energy-related taxes in the near future.[30][31] 87% of EU respondents and 85% of UK respondents believe that their governments are moving too slowly to halt climate change. Few respondents from the UK, EU, and the US believe that their governments will be successful in decreasing carbon emissions by 2030.[30]

According to the 2024 survey conducted in the European Union, 86% of Europeans believe that investing in climate change adaptation can lead to job creation and stimulate the local economy.[32] The same survey also reveals that 80% of respondents, including 89% from southern European countries, have encountered at least one extreme weather event over the last five years. Of these, 55% reported experiencing extreme heat and heatwaves, with higher occurrences in Spain (73%) and Romania (71%). Furthermore, 35% of respondents have been affected by droughts, with the incidence rising to 62% in Romania and 49% in Spain. Additionally, 34% have witnessed heavy storms or hail, with 62% in Slovenia and 49% in Croatia reporting such experiences.[33]

Older surveys (prior to 2013)

[edit]In Europe, the notion of human influence on climate gained wide acceptance more rapidly than in the United States and other countries (data from 2007).[34][35] A 2009 survey found that Europeans rated climate change as the second most serious problem facing the world, between "poverty, the lack of food and drinking water" and "a major global economic downturn". 87% of Europeans considered climate change to be a very serious or serious problem, while ten per cent did not consider it a serious problem.[36]

A 15-nation poll conducted in 2006, by Pew Global found that there "is a substantial gap in concern over global warming—roughly two-thirds of Japanese (66%) and Indians (65%) say they personally worry a great deal about global warming. Roughly half of the populations of Spain (51%) and France (46%) also express great concern over global warming, based on those who have heard about the issue. But there is no evidence of alarm over global warming in either the United States or China—the two largest producers of greenhouse gases. Just 19% of Americans and 20% of the Chinese who have heard of the issue say they worry a lot about global warming—the lowest percentages in the 15 countries surveyed. Moreover, nearly half of Americans (47%) and somewhat fewer Chinese (37%) express little or no concern about the problem."[37]

A 47-nation poll by Pew Global Attitudes conducted in 2007 found, "Substantial majorities 25 of 37 countries say global warming is a 'very serious' problem."[38]

Matthew C. Nisbet and Teresa Myers' 2007 article—"Twenty Years of Public Opinion about Global Warming"—covered two decades in the United States starting in 1980—in which they investigated public awareness of the causes and impacts of global warming, public policy, scientific consensus on climate change, public support for the Kyoto Accord, and their concerns about the economic costs of potential public policies that responded to climate change.[39] They found that from 1986 to 1990, the proportion of respondents who reported having heard about climate change increased from 39% to 74%. However, they noted "levels of overall understanding were limited".[14][39]

A 2010 journal article in Risk Analysis compared and contrasted a 1992[40] survey and a 2009 survey of lay peoples' awareness and opinions of climate change.[41] In 1992, the general public did not differentiate between climate change and the depletion of the ozone layer. Using a mental models methodology, researchers found that while there was a marked increase in understanding of climate change by 2009, many did not accept that global warming was "primarily due to increased concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere", or that the "single most important source of this carbon dioxide is the combustion of fossil fuels".[14][41]

Influences on individual opinion

[edit]Geographic region

[edit]

For a list of countries and their opinion see "By region and country", below.

The first major worldwide poll, conducted by Gallup in 2008–2009 in 127 countries, found that some 62% of people worldwide said they knew about global warming. In the industrialized countries of North America, Europe, and Japan, 67% or more knew about it (97% in the U.S., 99% in Japan); in developing countries, especially in Africa, fewer than a quarter knew about it, although many had noticed local weather changes. The survey results suggest that between 2007 and 2010 only 42% of the world's population were aware of climate change and believed that it is caused by human activity. Among those who knew about global warming, there was a wide variation between nations in belief that the warming was a result of human activities.[43][44]

Adults in Asia, with the exception of those in developed countries, are the least likely to perceive global warming as a threat. In developed Asian countries like South Korea, perceptions of climate change are associated with strong emotional beliefs about its causes.[45] In the western world, individuals are the most likely to be aware and perceive it as a very or somewhat serious threat to themselves and their families;[46] although Europeans are more concerned about climate change than those in the United States.[47] However, the public in Africa, where individuals are the most vulnerable to global warming while producing the least carbon dioxide, is the least aware – which translates into a low perception that it is a threat.[46]

These variations pose a challenge to policymakers, as different countries travel down different paths, making an agreement over an appropriate response difficult. While Africa may be the most vulnerable and produce the least greenhouse gases, they are the most ambivalent. The top five emitters (China, the United States, India, Russia, and Japan), who together emit half the world's greenhouse gases, vary in both awareness and concern. The United States, Russia, and Japan are the most aware at over 85% of the population. Conversely, only two-thirds of people in China and one-third in India are aware. Japan expresses the greatest concern of the five, which translates into support for environmental policies. People in China, Russia, and the United States, while varying in awareness, have expressed a similar proportion of aware individuals concerned. Similarly, those aware in India are likely to be concerned, but India faces challenges spreading this concern to the remaining population as its energy needs increase over the next decade.[48]

An online survey on environmental questions conducted in 20 countries by Ipsos MORI, "Global Trends 2014", shows broad agreement, especially on climate change and whether it is caused by humans, although the U.S. ranked lowest with 54% agreement.[49] It has been suggested that the low U.S. ranking is tied to denial campaigns.[50]

A 2010 survey of 14 industrialized countries found that skepticism about the danger of global warming was highest in Australia, Norway, New Zealand and the United States, in that order, correlating positively with per capita emissions of carbon dioxide.[51]

A survey conducted in the European Union in 2024 reveals that 50% of respondents see climate adaptation as a priority for their country in the upcoming years. Individuals residing in southern European nations are notably more concerned, with 65% considering adaptation a priority, which is 15 percentage points higher than the EU average.[52][53] The same survey found that 28% of respondents in the EU think that the elderly should be prioritized for support in climate change adaptation, and 23% believe that individuals residing in high-risk areas should be the first to receive support.

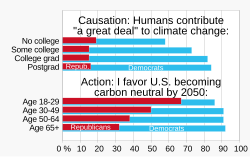

Education

[edit]

In countries varying in awareness, an educational gap translates into a gap in awareness.[54] However an increase in awareness does not always result in an increase in perceived threat. In China, 98% of those who have completed four or more years of college education reported knowing something or a great deal of climate change, while only 63% of those who have completed nine years of education reported the same. Despite the differences in awareness in China, all groups perceive a low level of threat from global warming. In India, those who are educated are more likely to be aware, and those who are educated there are far more likely to report perceiving global warming as a threat than those who are not educated.[48] In Europe, individuals who have attained a higher level of education perceive climate change as a serious threat. There is also a strong correlation between education and Internet use. Europeans who use the Internet more are more likely to perceive climate change as a serious threat.[55] However, a survey of American adults found "little disagreement among culturally diverse citizens[clarification needed] on what science knows about climate change. In the US, individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on climate change.[56]

In the US states of Washington, California, Oregon, and Idaho, people with more education were more likely to support the building of new fossil fuel power plants than people with less of an education.[57]

Demographics

[edit]In general, there is a substantial variation in the direction in which demographic traits, like age or gender, correlate with climate change concern. While women and younger people tend to be more concerned about climate change in English-speaking constituencies, the opposite is true in most African countries.[44][58]

Residential demographics affect perceptions of global warming. In China in 2008, 77% of those who lived in urban areas were aware of global warming compared to 52% in rural areas. This trend was mirrored in India with 49% to 29% awareness, respectively.[48]

Of the countries where at least half the population is aware of global warming, those with the majority who believe that global warming is due to human activities have a greater national GDP per unit energy—or, a greater energy efficiency.[59]

In Europe, individuals under fifty-five are more likely to perceive both "poverty, lack of food and drinking water" and climate change as a serious threat than individuals over fifty-five. Male individuals are more likely to perceive climate change as a threat than female individuals. Managers, white-collar workers, and students are more likely to perceive climate change as a greater threat than house persons and retired individuals.[55]

In the United States, conservative white men are more likely than other Americans to deny climate change.[60] Men are also less likely to believe that climate change is human caused or that there is a consensus message talking about the issues of climate change among scientists.[61] A very similar trend has been documented in Norway, where 63% of conservative men deny anthropogenic climate change compared to just 36% of the general Norwegian population.[62] In Sweden, political conservatism was similarly found to correlate with climate change denial, while in Brazil, climate change denial has been found to be more correlated with gender, with men being significantly more likely to express denialist viewpoints compared to women.[63]

Women are more likely to support egalitarian policies and well as social programs for their community. Although there are differences between men and women when it comes to environmental public policy, both are less likely to support policies such as ones for CO2 regulations if the economy is doing poorly.[61]

In Great Britain, a movement of by women known as "birthstrikers" advocates for refraining from procreation until the possibility of "climate breakdown and civilisation collapse" is averted.[64]

In 2021 a global survey was conducted to understand the opinion of people aged 16-25 about climate change. According to the study, 4 out of 10 are hesitating about having children because they are afraid of climate change, and 6 out of 10 feel extreme anxiety about the issue. Similar numbers felt betrayed by older generations and governments.[65]

Age differences

[edit]Youth show a deeper understanding and awareness of climate change than adults and older generations.[66] Younger generations of people typically demonstrate more concern about climate change than older generations, and younger demographics show more negative and pessimistic attitudes towards climate change.[67] With little ability to measure the awareness of varying-age demographics, it is difficult to understand the level of awareness that younger generations exemplify compared to older generations toward climate change. [67] However, younger demographics also believe at higher rates than older demographics that climate change can be successfully mitigated by taking action, and are more likely to express interest in taking action in order to help mitigate climate change.[67]

About 28% of millennials say that they have taken some kind of action to help with climate change, and 40% have used social media to address climate change in some way, along with 45% of Gen Z youth.[68] Younger generations are also more likely to support and vote for climate change policies than older generations.[68]

In the western US states of Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and California, older residents are more likely to support policies for building new fossil fuel power plants.[57]

Political identification

[edit]

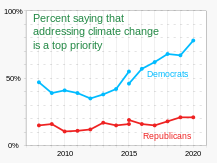

Public opinion on climate change can be influenced by who people vote for. Although media coverage influences how some view climate change, research shows that voting behavior influences climate change skepticism. This shows that people's views on climate change tend to align with the people they voted for.[72]

In Europe, opinion is not strongly divided among left and right parties. Although European political parties on the left, including Green parties, strongly support measures to address climate change, conservative European political parties maintain similar sentiments, most notably in Western and Northern Europe. For example, Margaret Thatcher, never a friend of the coal mining industry, was a strong supporter of an active climate protection policy and was instrumental in founding the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the British Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research.[73] Some speeches, as to the Royal Society on 27 September 1988[74] and to the UN general assembly in November 1989 helped to put climate change, acid rain, and general pollution in the British mainstream. After her career, however, Thatcher was less of a climate activist, as she called climate action a "marvelous excuse for supranational socialism", and called Al Gore an "apocalyptic hyperbole".[75] France's center-right President Chirac pushed key environmental and climate change policies in France in 2005–2007. Conservative German administrations (under the Christian Democratic Union and Christian Social Union) in the past two decades[when?] have supported European Union climate change initiatives; concern about forest dieback and acid rain regulation were initiated under Kohl's archconservative minister of the interior Friedrich Zimmermann. In the period after former President George W. Bush announced that the United States was leaving the Kyoto Treaty, European media and newspapers on both the left and right criticized the move. The conservative Spanish La Razón, the Irish Times, the Irish Independent, the Danish Berlingske Tidende, and the Greek Kathimerini all condemned the Bush administration's decision, as did left-leaning newspapers.[76]

In Norway, a 2013 poll conducted by TNS Gallup found that 92% of those who vote for the Socialist Left Party and 89% of those who vote for the Liberal Party believe that global warming is caused by humans, while the percentage who held this belief is 60% among voters for the Conservative Party and 41% among voters for the Progress Party.[77]

The shared sentiments between the political left and right on climate change further illustrate the divide in perception between the United States and Europe on climate change. As an example, conservative German Prime Ministers Helmut Kohl and Angela Merkel have differed with other parties in Germany only on how to meet emissions reduction targets, not whether or not to establish or fulfill them.[76]

A 2017 study found that those who changed their opinion on climate change between 2010 and 2014 did so "primarily to align better with those who shared their party identification and political ideology. This conforms with the theory of motivated reasoning: Evidence consistent with prior beliefs is viewed as strong and, on politically salient issues, people strive to bring their opinions into conformance with those who share their political identity".[78] Furthermore, a 2019 study examining the growing skepticism of climate change among American Republicans argues that persuasion and rhetoric from party elites play a critical role in public opinion formation, and that these elite cues are propagated through mainstream and social media sources.[79]

Those who care about the environment and want change are not happy about some policies, for example the cap and trade policy, but very few people are willing to pay more than 15 dollars per month for a program that is supposed to help the environment. According to a 2015 article published in Environmental Politics, while most Americans were aware of climate change, only 2% of respondents ranked the environment as the top issue in the US.[80]

A 2014–2018 survey of Oklahoma (U.S.) residents found that partisans on the political right have much more unstable beliefs about climate change than partisans on the left.[81] Contradicting previous literature indicating that climate beliefs are firmly held and invariable, the researchers said the results imply that opinions on the right are more susceptible to change.[81]

Individual risk assessment and assignment

[edit]The IPCC attempts to orchestrate global (climate) change research to shape a worldwide consensus according to a 1996 article.[82] However, the consensus approach has been dubbed more a liability than an asset in comparison to other environmental challenges.[83][84] In 2010, an article in Current Sociology, said that the linear model of policy-making, based on a more knowledge we have, the better the political response will be was said to have not been working and was in the meantime rejected by sociology.[85]

In a 1999 article, Sheldon Ungar, a Canadian sociologist, compared the different public reactions towards ozone depletion and climate change.[86] The public opinion failed to tie climate change to concrete events which could be used as a threshold or beacon to signify immediate danger.[86] Scientific predictions of a temperature rise of two to three degrees Celsius over several decades do not respond with people, e.g. in North America, that experience similar swings during a single day.[86] As scientists define global warming a problem of the future, a liability in "attention economy", pessimistic outlooks in general and assigning extreme weather to climate change have often been discredited or ridiculed (compare Gore effect) in the public arena.[87] While the greenhouse effect per se is essential for life on Earth, the case was quite different with the ozone shield and other metaphors about the ozone depletion. The scientific assessment of the ozone problem also had large uncertainties. But the metaphors used in the discussion (ozone shield, ozone hole) reflected better with lay people and their concerns.

The chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) regulation attempts of the end of the 1980s benefited from those easy-to-grasp metaphors and the personal risk assumptions taken from them. As well, the fate of celebrities like President Ronald Reagan, who had skin cancer removal in 1985 and 1987, was of high importance. In the case of public opinion on climate change, no imminent danger is perceived.[86]

It has been hypothesised many times that no matter how strong the climate knowledge provided by risk analysts, experts and scientists is, risk perception determines agents' ultimate response in terms of mitigation. However, recent literature reports conflicting evidence about the actual impact of risk perception on agents’ climate response. Rather, a no-direct perception-response link with the mediation and moderation of many other factors and a strong dependency on the context analysed is shown. Some moderation factors considered as such in the specialised literature include communication and social norms. Yet, conflicting evidence of the disparity between public communication about climate change and the lack of behavioural change has also been observed in the general public. Likewise, doubts are raised about the observance of social norms as an influencing predominant factor that affects action on climate change.[88] What is more, disparate evidence also showed that even agents highly engaged in mitigation (engagement is a mediation factor) actions fail ultimately to respond.[89]

Ideology and religion

[edit]

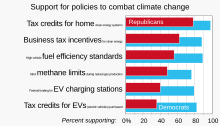

In the United States, ideology is an effective predictor of party identification, where conservatives are more prevalent among Republicans, and moderates and liberals among independents and Democrats.[91] A shift in ideology is often associated with in a shift in political views.[92] For example, when the number of conservatives rose from 2008 to 2009, the number of individuals who felt that global warming was being exaggerated in the media also rose.[93] The 2006 BBC World Service poll found that when asked about various policy options to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – tax incentives for alternative energy research and development, instalment of taxes to encourage energy conservation, and reliance on nuclear energy to reduce fossil fuels. The majority of those asked felt that tax incentives were the path of action that they preferred.

As of May 2016, polls have repeatedly found that a majority of Republican voters, particularly young ones, believe the government should take action to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.[94]

After a country hosts the annual Conference of the Parties (COP) climate legislation increases, which causes policy diffusion. There is strong evidence of policy diffusion, which is when a policy is made it is influenced by the policy choices made elsewhere.This can have a positive effect on climate legislation.[95]

Scientific analyses of international survey data show that right-wing orientation and individualism are strongly correlated to climate change denial in the US and other English-speaking countries, but much less in most non-English speaking nations.[44][96]

Political ideologies are seen as one of the most consistent factors of the support or rejection of climate change public policies.[97]

A person's political ideology is seen to affect the a person's cognitive and emotional appraisals which then affect how somebody sees climate change and if the dangers of it will inflict harm to them.[97]

Certain religious beliefs like end times theology have also been found to be correlated with climate change denial, though they are not as reliable as predictors of it as political conservatism is.[98]

Income

[edit]

Income has a strong influence on public opinion regarding policies such as building more fossil fuel power plants or whether we should lighten up on environmental standards in industries. People that have bigger incomes in the states of Washington, Oregon, California and Idaho are more likely to support the policy regarding building new power plants and support lightening up on environmental standards in industries compared to people with a smaller income.[57]

Economic factors

[edit]Development of climate change policies is influenced by economic conditions. For a long period of time, such conditions were seen to play an important role in influencing political behavior. Economic issues and environmental issues are often seen as a trade-off since something that helps one was believed to negatively affect the other. Accordingly, the environment is usually seen as a problem that is not as big and crucial as the economy.[61]

Visibility

[edit]Personal experience and noticing weather changes due to climate change are likely to motivate people to find solutions and act on them. After experiencing crop failures due to dry spells in Nepal, citizens were more likely find and incorporate adaptive strategies to fight thing from the vulnerability they face.[99]

Outside of studying the differences in perception of climate change in large geographic areas, researchers have studied the effects of visibility to the individual citizen. In the scientific and academic community, there is an ongoing debate about whether visibility or seeing the effects of climate change literally with one's own eyes is helpful. Though some scientists are dismissive of anecdotal evidence, direct accounts have been studied to better reach local communities and understand their perception of climate change.[100] Climate solutions presented to the public and the private sector have focused on bringing visual learning and practical everyday actions designed to promote further engagement such as community members conducting climate change tours and mapping the trees in their neighborhood.[101]

Risk perception, as opposed to risk assessment, was constantly evaluated in these smaller, local studies. In a 2018 study of those residing near the Everglades, a prominent wetland ecosystem in Florida, participation in outdoor recreational activities, and elevation and distance from the shoreline of their residential location from the mean sea-level affected one's support in environmental conservation policy.[102] Frequent beach goers and other outdoor recreational enthusiasts concerned by differing sea levels were cited to be potential likely mobilizers. Another 2018 study found 56% of the recreational fishermen polled in the area said "being able to see other wildlife" was very or extremely important, and 60% reported being "very much concerned" about the health of the Everglades ecosystem.[103] In key American cities, the visibility of water stress and/or proximity to bodies of water increased the strength of water conservation policy in that area.[104] Perceived shrinking water supply or flooding can be seen as motivating public stance on climate change. However, in arid areas where water was less visible, this brings up concerns of weaker policy in locales that truly need it.

Farmers in the Punjab region of Pakistan are now witnessing a significant decrease in rice production due to climate change. Those who rely on agriculture for their livelihood are the most concerned, based on a 2014 study of 450 households. More than half of those households adapted their farming to climate change.[105]

Bodies of water and water scarcity, though very prominent concepts in this field of study, are not the only major factors when weighing the idea of visible climate change. For example, a 2021 study on the citizens' perception of geohazards was conducted in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy as part of the European Project RESPONSe (Interreg Italy–Croatia). Younger people were shown to be more invested in individual environmental impact versus older adults who were concerned about geohazards. The study was split between those who lived in the hinterlands and low coastal areas. Those shown living in the hinterlands were more inclined to be wary of geohazards and their risks. As those areas were said to be more susceptible to natural disasters, the study highlighted a larger awareness of natural hazards by those who historically are more vulnerable due to their proximity. While residents in general were aware due to their closeness to water sources, research also implies that there is translation needed between the framing of climate change and the immediate impacts to their living area for those who did not live in particularly affected areas.[106]

There are other factors when it comes to visibility for the individual and personally witnessing climate change. While education has been aforementioned and studied as a factor, materials of one's study have also been investigated as a factor of visibility. After studying Portuguese public higher education institutions in 2021, those in the natural and environmental sciences are more inclined to do environment-friendly practices such as recycle and willingness to work for lower salaries for companies that commit to climate change action. Students in the sciences and engineering majors were least likely to do so. While this result can be attributed to initial interest in those areas to begin with, most students were said to be concerned about climate change and said that there needed to be more material about climate change needed to be implemented in their institution's curriculum. Younger students were more likely to be extremely concerned, although the authors' speculated this to be a product of greater social media literacy.[107]

Social media

[edit]

Across different cultures and languages, the use of social media as a news source is associated with lower levels of climate skepticism.[5] A particular dynamic of social media discussion of climate change is the platform it provides for direct engagement by activists. In a study of the use of the comments sections on YouTube videos relating to climate change, for instance, a core group of users—both climate activists and skeptics—appeared repeatedly across these comments sections, with the majority taking a climate activist standpoint.[109] Although often criticised as reinforcing rather than challenging users' view, social media has also been shown to have a role in cognitive reflection. A study of fora on Reddit highlighted that "while some communities are dominated by particular ideological viewpoints, others are more suggestive of deliberative debate."[110]

Voicing believed wrongdoings

[edit]People can find motivation to act in the climate change movement when they are acting in the way to express disagreement with the decisions made by a higher power. In a 2017 Earth Day march, a majority of scientists and nonscientists were both seen to join the march to speak up to the Trump administration about what they have done regarding climate change. In addition, people felt motivated to join the march to protect the use of science to benefit the community and for its use in public good.[111]

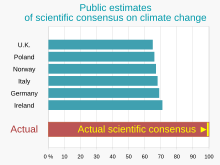

Understanding of scientific consensus

[edit]

A scientific consensus on climate change exists, as recognized by national academies of science and other authoritative bodies. However, research has identified substantial geographical variation in the public's understanding of the scientific consensus.[116]

There are marked differences between the opinion of scientists and that of the general public.[117][118] A 2009 poll in the US found "[w]hile 84% of scientists say the earth is getting warmer because of human activity such as burning fossil fuels, just 49% of the public agrees".[119] A 2010 poll in the UK for the BBC showed "Climate scepticism on the rise".[120] Robert Watson found this "very disappointing" and said "We need the public to understand that climate change is serious so they will change their habits and help us move towards a low carbon economy."[120]

A poll in 2009 regarding the issue of whether "some scientists have falsified research data to support their own theories and beliefs about global warming" showed that 59% of Americans believed it "at least somewhat likely", with 35% believing it was "very likely".[121]

A 2018 study found that individuals were more likely to accept that global temperatures were increasing if they were shown the information in a chart rather than in text.[122][123]

Media coverage

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (December 2021) |

The popular media in the U.S. gives greater attention to skeptics relative to the scientific community as a whole, and the level of agreement within the scientific community has not been accurately communicated.[124][125][better source needed] US popular media coverage differs from that presented in other countries, where reporting is more consistent with the scientific literature.[126] Some journalists attribute the difference to climate change denial being propagated, mainly in the US, by business-centered organizations employing tactics worked out previously by the US tobacco lobby.[127][128][129] However, one study suggests that these tactic are less prominent in the media and that the public instead draws their opinions on climate mainly from the cues of political party elites.[130]

The efforts of Al Gore and other environmental campaigns have focused on the effects of global warming and have managed to increase awareness and concern, but despite these efforts, as of 2007, the number of Americans believing humans are the cause of global warming was holding steady at 61%, and those believing that the popular media was understating the issue remained at about 35%.[131] Between 2010 and 2013, the number of Americans who believe the media under-reports the seriousness of global warming has been increasing, and the number who think media overstates it has been falling. According to a 2013 Gallup US opinion poll, 57% believe global warming is at least as bad as portrayed in the media (with 33% thinking media has downplayed global warming and 24% saying coverage is accurate). Less than half of Americans (41%) think the problem is not as bad as media portrays it.[132]

Another cause of climate change denial may be weariness from overexposure to the topic: some polls suggest that the public may have been discouraged by extremism when discussing the topic,[133] while other polls show 54% of U.S. voters believe that "the news media make global warming appear worse than it really is."[134]

A study published in PLOS One in 2024 found that even a single repetition of a claim was sufficient to increase the perceived truth of both climate science-aligned claims and climate change skeptic/denial claims—"highlighting the insidious effect of repetition".[135] This effect was found even among climate science endorsers.[135]

Impacts of public opinion on politics

[edit]

Public opinion impacts on the issue of climate change because governments need willing electorates and citizens in order to implement policies that address climate change. Further, when climate change perceptions differ between the populace and governments, the communication of risk to the public becomes problematic. Finally, a public that is not aware of the issues surrounding climate change may resist or oppose climate change policies, which is of considerable importance to politicians and state leaders.[136]

Public support for action to forestall global warming is as strong as public support has been historically for many other government actions; however, it is not "intense" in the sense that it overrides other priorities.[136][137]

A 2017 journal article said that shifts in public opinion in the direction of pro-environmentalism strongly increased the adoption of renewable energy policies in Europe.[138] A 2020 journal article said that countries in which more people believe in human-made climate change tend to have higher carbon prices.[139]

According to a 2011 Gallup poll, the proportion of Americans who believe that the effects of global warming have begun or will begin in a few years rose to a peak in 2008 where it then declined, and a similar trend was found regarding the belief that global warming is a threat to their lifestyle within their lifetime.[140] Concern over global warming often corresponds with economic downturns and national crisis such as 9/11 as Americans prioritize the economy and national security over environmental concerns. However the drop in concern in 2008 is unique compared to other environmental issues.[93] Considered in the context of environmental issues, Americans consider global warming as a less critical concern than the pollution of rivers, lakes, and drinking water; toxic waste; fresh water needs; air pollution; damage to the ozone layer; and the loss of tropical rain forests. However, Americans prioritize global warming over species extinction and acid rain issues.[141] Since 2000 the partisan gap has grown as Republican and Democratic views diverge.[142]

By region and country

[edit]

Climate change opinion is the aggregate of public opinion held by the adult population. Cost constraints often restrict surveys to sample only one or two countries from each continent or focus on only one region. Because of differences among questions, wording, and methods—it is difficult to reliably compare results or to generalize them to opinions held worldwide.

In 2007–2008, the Gallup Poll surveyed individuals from 128 countries in the first comprehensive study of global opinions. The Gallup Organization aggregated opinion from the adult population fifteen years of age and older, either through the telephone or personal interviews, and in both rural and urban areas except in areas where the safety of interviewer was threatened and in scarcely populated islands. Personal interviews were stratified by population size or geography and cluster sampling was achieved through one or more stages. Although error bounds vary, they were all below ±6% with 95% confidence.

Weighting countries to a 2008 World Bank population estimate, 61% of individuals worldwide were aware of global warming, developed countries more aware than developing, with Africa the least aware. The median of people perceiving it as a threat was 47%. Latin America and developed countries in Asia led the belief that climate change was a result of human activities, while Africa, parts of Asia and the Middle East, and countries from the Former Soviet Union led in the opposite. Awareness often translates to concern, although of those aware, individuals in Europe and developed countries in Asia perceived global warming as a greater threat than others.

In January 2021, the UNDP worked with Oxford University to release the world's largest survey of public opinion on climate change.[143] It surveyed 50 countries, spanning all inhabited regions, and a majority of the world's population. Its finding suggested a growing concern for climate change. Overall, 64% of respondents believed climate change was an emergency. This belief was high among all regions, the highest being Western Europe and North America at 72%, and the lowest being Sub-Saharan Africa at 61%. It also identified a link between average income and concern for climate change. In the high income countries, 72% believed it was an emergency. This was 62% for middle income countries and 58% for low income countries. It asked people whether or not they supported 18 key policies over 6 areas, ranging from economy to transport. There was general support for all policy suggestions. For example, 8 of the 10 countries with the highest emissions saw a majority of respondents favor more renewable energy. The general impression was that the public wanted more policies to be implemented, and demanded more from policy makers. Overall, 59% of respondents who believed climate change was an emergency said the world should do 'everything necessary and urgently in response' to the crisis. Conversely, there was remarkably little support among respondents for no policies at all, with the highest being Pakistan at only 5%. The report indicated a widespread public awareness, concern, and desire for greater action among all regions of the world.

Using the Pew Research Center's 2015 Global Attitudes Survey, the journal article entitled Cross-national variation in determinants of climate change concern found that the most consistent predictor of concern about climate change in 36 countries surveyed proved to be 'commitment to democratic principles'. Believing that free elections, freedom of religion, equal rights for women, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and lack of Internet censorship were 'very' rather than 'somewhat' important increased the probability of believing climate change is a very serious problem by 7 to 25 percent points in 26 of the 36 nations surveyed. It was the strongest predictor in 17.[144]

Global North compared to Global South

[edit]Awareness about climate change is higher in developed countries than in developing countries.[145] A large majority of people in Indonesia, Pakistan and Nigeria did not know about climate change in 2007, particularly in Muslim-majority countries.[145] There is often awareness about environmental changes in developing countries, but the framework for understanding it is limited. In both developing and developed countries, people similarly believe that poor countries have a responsibility to act on climate change.[145] Since the 2009 Copenhagen summit, concern over climate change in wealthy countries has diminished. In 2009, 63% of people in OECD member states considered climate change to be "very serious", but by 2015, only 48% did.[146] Support for national leadership addressing climate change has also diminished. Of the 21 countries surveyed in GlobeScan's 2015 survey, Canada, France, Spain and the UK are the only ones with a majority of the population supporting further action by their leaders to meet Paris climate accord emission targets.[146] While concern and desire for action has dropped in developed countries, awareness is higher; since 2000, twice as many people connect extreme weather events to human-caused climate change.[146]

While climate change affects the entire planet, opinions about these affects vary significantly among regions of the world. The Middle East has one of the lowest rates of concern in the world, especially compared to Latin America.[147] Europe and Africa have mixed views on climate change but lean towards action by a significant degree. Europeans focus substantially on climate change in comparison to United States residents, who are less concerned than the global median,[148] even as the United States remains the second biggest emitter in the world.[149] Droughts/water shortages are one of the biggest fears experienced about the impacts of climate change, especially in Latin America and Africa.[147] Developed countries in Asia have levels of concern about climate change similar to Latin America, which has one of the highest rates of concern. This is surprising as developing countries in Asia have levels of worry similar to the Middle East, one of the areas with the lowest levels.[150] Large emitters such as China usually ignore issues surrounding climate change as people in China have very low levels of concern about it.[150] The only significant exceptions to this tendency by large emitters are Brazil and India. India is the third-biggest while Brazil is the eleventh-biggest emitter in the world; both have high levels of concern about climate change, similar to much of Latin America.[147][149]

Africa

[edit]People in Africa are relatively concerned about climate change compared to the Middle East and parts of Asia. However, they are less concerned than most of Latin America and Europe. In 2015, 61% of people in Africa considered climate change to be a very serious problem, and 52% believe that climate change is harming people now. While 59% of Africans were worried about droughts or water shortages, only 16% were concerned about severe weather, and 3% are concerned about rising sea levels.[147] By 2007, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa were especially troubled about increasing desertification even as they account for .04% of global carbon dioxide emissions.[151] In 2011, concern in Sub-Saharan Africa over climate change dropped; only 34% of the population considered climate change to be a "very" or "somewhat serious issue".[150] Even so, according to the Pew Research Center 2015 Global Attitudes Survey, some countries were more concerned than others. In Uganda, 79% of people, 68% in Ghana, 45% in South Africa and 40% in Ethiopia considered climate change to be a very serious problem.[147]

In 2022, 51% of African respondents to a survey claimed climate change is one of the biggest problems they are facing. 41% saw inflation and 39% saw access to health care as the biggest issues.[152] 76% responded that they prefer renewable energy as the main source of energy and 3 out of 4 respondents want renewable energy to be prioritized. 13% cite using fossil fuels.[152]

Latin America

[edit]Latin America has a higher percentage of people concerned with climate change than other regions of the world. According to the Pew Research Center 74% consider climate change to be a serious problem and 77% say that it is harming people now, 20 points higher than the global median.[147] The same study showed that 63% of people in Latin America are very concerned that climate change will harm them personally.[147] When looked at more specifically, people in Mexico and Central America are the most worried, with 81.5% believing that climate change is a very serious issue. South America is slightly less anxious at 75% and the Caribbean, at the relatively high rate of 66.7%, is the least concerned.[153] Brazil is an important country in global climate change politics because it is the eleventh largest emitter and unlike other large emitter countries, 86% consider global warming to be a very serious problem.[147][154] Compared to the rest of the world, Latin America is more consistently concerned with high percentages of the population worried about climate change. Further, in Latin America, 67% believe in personal responsibility for climate change and say that people will have to make major lifestyle modifications.[147]

Europe

[edit]

Europeans have a tendency to be more concerned about climate change than much of the world, with the exception of Latin America. However, there is a divide between Eastern Europe, where people are less worried about climate change, and Western Europe. A global climate survey by the European Investment Bank showed that climate is the number one concern for Europeans. Most respondents said they were already feeling the effects of climate change. Many people believed climate change can still be reversed with 68% of Spanish respondents believing it can be reversed and 80% seeing themselves as part of the solution.[155]

In Europe, there is a range from 88% to 97% of people feeling that climate change is happening and similar ranges are present for agreeing that climate change is caused by human activity and that the impacts of it will be bad.[154] Generally Eastern European countries are slightly less likely to believe in climate change, or the dangers of it, with 63% saying it is very serious, 24% considering it to be fairly serious and only 10% saying it is not a serious problem.[157] When asked if they feel a personal responsibility to help reduce climate change, on a scale of 0, not at all, to 10, a great deal, Europeans respond with the average score of 5.6.[154] When looked at more specifically, Western Europeans are closer to the response of 7 while Eastern European countries respond with an average of less than 4. When asked if Europeans are willing to pay more for climate change, 49% are willing, however only 9% of Europeans have already switched to a greener energy supply.[157] While a large majority of Europeans believe in the dangers of climate change, their feelings of personal responsibility to deal with the issue are much more limited. Especially in terms of actions that could already have been taken - such as having already switched to greener energies discussed above - one can see Europeans' feelings of personal responsibility are limited. 90% of Europeans interviewed for the European Investment Bank Climate Survey 2019 believe their children will be impacted by climate change in their everyday lives and 70% are willing to pay an extra tax to fight climate change.[155]

According to the European Investment Bank's climate survey from 2022, the majority of Europeans believe that the conflict in Ukraine encourages them to conserve energy and lessen their reliance on fossil fuels, with 66% believing that the invasion's effects on the price of oil and gas should prompt actions to speed up the transition to a greener economy. This opinion is shared by responders from Britain and China, while Americans are divided.[30]

Many people believe that the government should take a role in fostering individual behavioral changes to engage in climate change mitigation. Two-thirds of Europeans (66%) support harsher government measures requiring people to adjust their behavior in order to combat climate change (72% of respondents under 30 would welcome such restrictions).[158]

Several survey studies found different types of opinions about climate change in society. For example, scholars have described "Global Warming's Five Germanys" or "Global Waming's Six Americas".[159] For Germany, these types include Alarmed Actives, Convinced, Cautious, Disengaged, and Dismissive.[160]

Asia/Pacific

[edit]Asia and the Pacific have a tendency to be less concerned about climate change, except small island states, with developing countries in Asia being less concerned than developed countries. In Asia and the Pacific, around 45% of people believe that climate change is a very serious problem and similarly 48% believe that it is harming people now.[147] Only 37% of people in Asia and the Pacific are very concerned that climate change will harm them personally.[147] There is a large gap between developing Asia and developed Asia. Only 31% of developing Asia considers global warming to be a "very" or "somewhat" serious threat and 74% of developed Asia considers global warming to be a serious threat.[150] It could be argued that one reason for this is that people in more developed countries in Asia are more educated on the issues, especially given that developing countries in Asia do face significant threats from climate change. The most relevant views on climate change are those of the citizens in the countries that are emitting the most. For example, in China, the world's largest emitter,[149] 68% of Chinese people are satisfied with their government's efforts to preserve the environment.[161] And in India, the world's third largest emitter,[149] 77% of Indian people are satisfied with their country's efforts to preserve the environment.[161] 80% of Chinese citizens interviewed in the European Investment Bank Climate Survey 2019 believe climate change is still reversible, 72% believe their individual behaviour can make a difference in addressing climate change.[155]

India

[edit]A research team led by Yale University's Anthony Leiserowitz, conducted an audience segmentation analysis in 2011 for India—"Global Warming's Six Indias",[162] The 2011 study broke down the Indian public into six distinct audience groups based on climate change beliefs, attitudes, risk perceptions and policy preferences: informed (19%), experienced (24%), undecided (15%), unconcerned (15%), indifferent (11%), and the disengaged (16%). While the informed are the most concerned and aware of climate change and its threats, the disengaged do not care or have an opinion. The experienced believe it is happening or have felt the effects of climate change and can identify it when provided with a short description. The undecided, unconcerned and indifferent, all have varying levels of worry, concern and risk perception.

The same survey resulted in a different study, "Climate Change in the Indian Mind"[163] showing that 41% of respondents had either never heard of the term global warming, or did not know what it meant while 7% claimed to know "a lot" about global warming. When provided with a description of global warming and what it might entail, 72% of the respondents agreed that it was happening. The study revealed that 56% of respondents perceived it to be caused by human activities while 31% perceived it to be caused primarily by natural changes in the environment. 54% agreed that hot days had become more frequent in their local area, in comparison to 21% of respondents perceiving frequency of severe storms as having increased. A majority of respondents (65%) perceived a severe drought or flood as having a medium to large impact on their lives. These impacts include effects on drinking water, food supply, healthy, income and their community. Higher education levels tended to correspond with higher levels of concern or worry regarding global warming and its effects on them personally.

41% of the respondents agreed that the government should be doing more to address issues stemming from climate change, with the most support (70%) for a national program to elevate climate literacy. 53% of respondents agreed that protecting the environment is important event at a cost to economic growth, highlighting the tendency of respondents to display egalitarian over individualistic values.[164] Personal experiences with climate change risks are an important predictor of risk perception and policy support. Coupled with trust in different sources, mainly scientists and environmental organizations, higher usage of media and attention to news,[165] policy support, public engagement and belief in global warming are seen to increase.

Pakistan

[edit]Middle East

[edit]While the increasing severity of droughts and other dangerous realities are and will continue to be a problem in the Middle East, the region has one of the smallest rates of concern in the world. 38% believe that climate change is a very serious problem and 26% believe that climate change is harming people now.[147] Of the four Middle Eastern countries polled in a Pew Global Study, on what is their primary concern, Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon named ISIS, and Turkey stated United States encroachment.[167] 38% of Israel considers climate change to be a major threat to their country, 40% of Jordan, 58% of Lebanon and 53% of Turkey.[167] This is compared to relatively high numbers of residents who believe that ISIS is a major threat to their country ranging from 63% to 97%. In the poll, 38% of the Middle East are concerned about drought and 19% are concerned about long periods of unusually hot weather.[147] 42% are satisfied with their own country's current efforts to preserve the environment.[161]

North America

[edit]North America has mixed perceptions on climate change ranging from Mexico and Canada that are both more concerned, and the United States, the world's second largest emitter,[149] that is less concerned. Mexico is the most concerned about climate change of the three countries in North America. 90% consider climate change to be a very serious problem and 83% believe that climate change is harming people substantially right now.[168] Canadians are also seriously concerned, 20% are extremely concerned, 30% are definitely concerned, 31% are somewhat concerned and only 19% are not very/not at all concerned about climate change.[169] While the United States which is the largest emitter of CO2 in North America and the second largest emitter of CO2 in the world[149] has the lowest degrees of concern about climate change in North America. While 61% of Americans say they are concerned about climate change,[148] that is 30% lower than Mexico and 20% lower than Canada. 41% believe that climate change could impact them personally. Nonetheless, 70% of Americans believe that environmental protections are more important than economic growth according to a Yale climate opinion study.[148] 76% of US citizens interviewed for the European Investment Bank Climate Survey 2019 believe developed countries have a responsibility to help developing countries address climate change.[155]

United States

[edit]In the U.S. global warming is nowadays often a partisan political issue.[174] Republicans tend to oppose action against a threat that they regard as unproven, while Democrats tend to support actions that they believe will reduce global warming and its effects through the control of greenhouse gas emissions.[175]

In the United States, support for environmental protection was relatively non-partisan in the twentieth century. Republican Theodore Roosevelt established national parks whereas Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the Soil Conservation Service. Republican Richard Nixon was instrumental in founding the United States Environmental Protection Agency, and tried to install a third pillar of NATO dealing with environmental challenges such as acid rain and the greenhouse effect. Daniel Patrick Moynihan was Nixon's NATO delegate for the topic.[176]

This non-partisanship began to erode during the 1980s, when the Reagan administration described environmental protection as an economic burden. Views over global warming began to seriously diverge between Democrats and Republicans during the negotiations that led up to the creation of the Kyoto Protocol in 1998. In a 2008 Gallup poll of the American public, 76% of Democrats and only 41% of Republicans said that they believed global warming was already happening. The opinions of the political elites, such as members of Congress, tends to be even more polarized.[177]

One public survey out of Yale University concluded that there are "Six Americas"[159] as it pertains to categories of public opinion on climate change (or Global Warming, per the survey). These "Six Americas" are:

- Alarmed: These individuals are convinced that climate change is happening, human-caused, and a serious threat. They actively support societal and political actions to address it.

- Concerned: While not as convinced or engaged as the Alarmed group, the Concerned individuals still see climate change as a problem and are supportive of actions to address it.

- Cautious: This group is uncertain about whether climate change is happening, and if it is, they believe it is a distant threat. They are less likely to support climate-related policies.

- Disengaged: The Disengaged have little awareness or understanding of climate change and are not actively paying attention to the issue.

- Doubtful: This group is skeptical about climate change, believing that if it is happening, it is due to natural causes and is not a serious concern.

- Dismissive: The Dismissive individuals are actively convinced that climate change is not happening or is not a concern. They often reject the scientific consensus on the issue.

The "Six Americas" framework[159] has aided in the development of more understanding climate change perception, behavior, adaptation and belief. In 2016, Shirley Fiske published a report which built on the "Six Americans" framework in order to identify the core cultural models from which Maryland farmers relate to and have opinions about climate change.[178]

The two cultural models Fiske developed are:

- "Climate change as natural change": The farmers studied interpreted changes in climate as natural phenomena

- "Climate change as environmental change": From this perspective, climate change is a human-driven environmental problem, which requires human action to reverse or mitigate

References

[edit]- ^ Leiserowitz, A.; Carman, J.; Buttermore, N.; Wang, X.; et al. (June 2021). International Public Opinion on Climate Change (PDF). New Haven, CT, U.S.: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and Facebook Data for Good. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2021.

- ^ ● Survey results from: "The Peoples' Climate Vote". UNDP.org. United Nations Development Programme. 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Fig. 3.

● Data re top emitters from: "Historical GHG Emissions / Global Historical Emissions". ClimateWatchData.org. Climate Watch. 2021. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. - ^ Shwom, Rachael; McCright, Aaron; Brechin, Steven; Dunlap, Riley; Marquart-Pyatt, Sandra; Hamilton, Lawrence (October 2015). "Public Opinion on Climate Change". Climate Change and Society. pp. 269–299. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199356102.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-935610-2. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Antilla, Liisa (1 March 2010). "Self-censorship and science: a geographical review of media coverage of climate tipping points". Public Understanding of Science. 19 (2): 240–256. doi:10.1177/0963662508094099. ISSN 0963-6625. S2CID 143093512.

- ^ a b Diehl, Trevor; Huber, Brigitte; Gil de Zúñiga, Homero; Liu, James (18 November 2019). "Social Media and Beliefs about Climate Change: A Cross-National Analysis of News Use, Political Ideology, and Trust in Science". International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 33 (2): 197–213. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edz040. ISSN 0954-2892.

- ^ "The Peoples' Climate Vote". UNDP.org. United Nations Development Programme. 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021.

64% of people said that climate change was an emergency – presenting a clear and convincing call for decision-makers to step up on ambition.

- The highest level of support was in SIDS (Small Island Developing States, 74%), followed by high-income countries (72%), middle-income countries (62%), then LDCs (Least Developed Countries, 58%).

- Regionally, the proportion of people who said climate change is a global emergency was high everywhere - in Western Europe and North America (72%), Eastern Europe and Central Asia (65%), Arab States (64%), Latin America and Caribbean (63%), Asia and Pacific (63%), and Sub-Saharan Africa (61%).

- Four climate policies emerged as the most popular globally:

1. Conservation of forests and land (54% public support);

2. Solar, wind and renewable power (53%);

3. Climate-friendly farming techniques (52%); and

4. Investing more in green businesses and jobs (50%).

(Page has download link to 68-page PDF.) - ^ McGrath, Matt (27 January 2021). "Climate change: Biggest global poll supports 'global emergency'". BBC. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Public perceptions on climate change" (PDF). PERITIA Trust EU - The Policy Institute of King's College London. June 2022. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2022.

- ^ Powell, James (20 November 2019). "Scientists Reach 100% Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming". Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 37 (4): 183–184. doi:10.1177/0270467619886266. S2CID 213454806.

- ^ Lynas, Mark; Houlton, Benjamin Z.; Perry, Simon (19 October 2021). "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114005. Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966. S2CID 239032360.

- ^ Myers, Krista F.; Doran, Peter T.; Cook, John; Kotcher, John E.; Myers, Teresa A. (20 October 2021). "Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (10): 104030. Bibcode:2021ERL....16j4030M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2774. S2CID 239047650.

- ^ Poushter, Jacob; Fagan, Moira; Gubbala, Sneha (31 August 2022). "Climate Change Remains Top Global Threat Across 19-Country Survey". pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. — Other threats in the survey were: spread of false information online, cyberattacks from other countries, condition of the global economy, and spread of infectious diseases.

- ^ "Peoples' Climate Vote 2024 / Results" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 20 June 2024. p. 68. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2024. (from p. 16: "Seventy seven countries were chosen to provide results for the different regions of the world, representative of a huge majority (87 percent) of the world's population.")

- ^ a b c Capstick, Stuart; Whitmarsh, Lorraine; Poortinga, Wouter; Pidgeon, Nick; Upham, Paul (2015). "International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century". WIREs Climate Change. 6 (1): 35–61. Bibcode:2015WIRCC...6...35C. doi:10.1002/wcc.321. ISSN 1757-7799. S2CID 143249638. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "World Risk Poll 2021: A Resilient World? Understanding vulnerability in a changing climate" (PDF). lrfoundation.org.uk. 2022.

- ^ Alkousaa, Riham (19 October 2022). "Concern about climate change shrinks globally as threat grows - study". Reuters. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "High experience of disasters often correlates with low resilience". The Lloyd's Register Foundation World Risk Poll. 20 September 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ 67 per cent of young Brits want a socialist economic system, finds new poll.

- ^ "80 percent of people globally want stronger climate action by governments according to UN Development Programme survey". UNDP. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Ricketts, Emma (25 March 2024). "Few voters globally worried about climate change". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ a b "2021–2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 1 of 3: Europeans sceptical about successfully reducing carbon emissions by 2050, American and Chinese respondents more confident". EIB.org. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "2022-2023 EIB Climate Survey, part 1 of 2: Majority of Europeans say the war in Ukraine and high energy prices should accelerate the green transition". EIB.org. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Three-quarters of adults in Great Britain worry about climate change - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Future of Europe: Europeans see climate change as top challenge for the EU | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Energy poverty". energy.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Site is undergoing maintenance". Agenparl - L'Informazione indipendente (in Italian). Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "In focus: Energy efficiency – a driver for lower energy bills". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Council adopts regulation on reducing gas demand by 15% this winter". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Survey: Ukraine energy price crisis to spur climate transition". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ "2022-2023 EIB Climate Survey, part 1 of 2: Majority of Europeans say the war in Ukraine and high energy prices should accelerate the green transition". EIB.org. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "The EIB Climate Survey". European Investment Bank.

- ^ "The EIB Climate Survey". European Investment Bank.

- ^ Crampton, Thomas (4 January 2007). "More in Europe worry about climate than in U.S., poll shows". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ "Little Consensus on Global Warming – Partisanship Drives Opinion – Summary of Findings". Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 12 July 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ TNS Opinion and Social (December 2009). "Europeans' Attitudes Towards Climate Change" (Full free text). European Commission. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ^ No Global Warming Alarm in the U.S., China Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine 15-Nation Pew Global Attitudes Survey, released 13 June 2006.

- ^ Rising Environmental Concern in 47-Nation Survey Archived 12 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Pew Global Attitudes. Released 27 June 2007.

- ^ a b Nisbet, Matthew C.; Myers, Teresa (1 January 2007). "The Polls—Trends: Twenty Years of Public Opinion about Global Warming". Public Opinion Quarterly. 71 (3): 444–470. doi:10.1093/poq/nfm031. ISSN 0033-362X.

- ^ Read, Daniel; Bostrom, Ann; Morgan, M. Granger; Fischhoff, Baruch; Smuts, Tom (1994). "What Do People Know About Global Climate Change? 2. Survey Studies of Educated Laypeople". Risk Analysis. 14 (6): 971–982. Bibcode:1994RiskA..14..971R. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1994.tb00066.x. ISSN 1539-6924.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Travis William; Bostrom, Ann; Read, Daniel; Morgan, M. Granger (October 2010). "Now what do people know about global climate change? Survey studies of educated laypeople". Risk Analysis. 30 (10): 1520–1538. Bibcode:2010RiskA..30.1520R. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01448.x. ISSN 0272-4332. PMC 6170370. PMID 20649942.

- ^ "Global Views on Climate Change" (PDF). Ipsos. November 2023. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2023.

- ^ Pelham, Brett (2009). "Awareness, Opinions about Global Warming Vary Worldwide". Gallup. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Levi, Sebastian (26 February 2021). "Country-level conditions like prosperity, democracy, and regulatory culture predict individual climate change belief". Communications Earth & Environment. 2 (1): 51. Bibcode:2021ComEE...2...51L. doi:10.1038/s43247-021-00118-6. ISSN 2662-4435. S2CID 232052935.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - ^ Anghelcev, George; Chung, Mun Young; Sar, Sela; Duff, Brittany (2015). "A ZMET-based analysis of perceptions of climate change among young South Koreans: Implications for social marketing communication". Journal of Marketing Communications. 5 (1): 56–82. doi:10.1108/JSOCM-12-2012-0048.

- ^ a b Pugliese, Anita; Ray, Julie (11 December 2009). "Awareness of Climate Change and Threat Vary by Region". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Crampton, Thomas (1 January 2007). "More in Europe worry about climate than in U.S., poll shows". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ a b c Pugliese, Anita; Ray, Julie (7 December 2009). "Top-Emitting Countries Differ on Climate Change Threat". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Ipsos MORI. "Global Trends 2014". Archived from the original on 23 February 2015.

- ^ MotherJones (22 July 2014). "The Strange Relationship Between Global Warming Denial and...Speaking English".

- ^ Tranter, Bruce; Booth, Kate (July 2015). "Scepticism in a Changing Climate: A Cross-national Study". Global Environmental Change. 33: 54–164. Bibcode:2015GEC....33..154T. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.05.003.

- ^ "The EIB Climate Survey". European Investment Bank.

- ^ "94% of Europeans support measures to adapt to climate change, according to EIB survey". www.eib.org. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "The culture awareness-education gap is growing". Human Synergistics. 14 June 2017.

- ^ a b TNS Opinion and Social (November 2009). Europeans' Attitudes Towards Climate Change (PDF) (Report). European Commission. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ^ Drummond, Caitlin; Fischhoff, Baruch (5 September 2017). "Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (36): 9587–9592. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.9587D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704882114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5594657. PMID 28827344.

- ^ a b c Allen Wolters, Erika; Steel, Brent S.; Warner, Rebecca L. (13 April 2020). "Ideology and Value Determinants of Public Support for Energy Policies in the U.S.: A Focus on Western States". Energies. 13 (8): 1890. doi:10.3390/en13081890. ISSN 1996-1073.

- ^ Lewis, Gregory B.; Palm, Risa; Feng, Bo (29 July 2019). "Cross-national variation in determinants of climate change concern". Environmental Politics. 28 (5): 793–821. Bibcode:2019EnvPo..28..793L. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1512261. ISSN 0964-4016. S2CID 158362184.

- ^ Pelham, Brett W. (24 April 2009). "Views on Global Warming Relate to Energy Efficiency". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ McCright, Aaron M.; Dunlap, Riley E. (October 2011). "Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States". Global Environmental Change. 21 (4): 1163–1172. Bibcode:2011GEC....21.1163M. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003.

- ^ a b c Arbuckle, Matthew; Mercer, Makenzie (June 2020). "Economic outlook and the gender gap in attitudes about climate change". Population and Environment. 41 (4): 422–451. Bibcode:2020PopEn..41..422A. doi:10.1007/s11111-020-00343-9. ISSN 0199-0039. S2CID 216226618.

- ^ Krange, Olve; Kaltenborn, Bjorn P.; Hultman, Martin (5 July 2018). "Cool dudes in Norway: climate change denial among conservative Norwegian men". Environmental Sociology. 5 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/23251042.2018.1488516. hdl:11250/2559408. S2CID 134964754.