Flag of Puerto Rico

| |

| |

| Use | Civil and state flag, civil and state ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | August 3, 1995 by elected Puerto Rican government after issuing regulation identifying colors but not specifying color shades; medium blue replaced dark blue as de facto shade of triangle[1] |

| |

| |

| Use | Civil and state flag, civil and state ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | July 24, 1952 by elected Puerto Rican government with the establishment of the commonwealth after issuing law identifying colors but not specifying color shades; dark blue became de facto shade of triangle, replacing presumed original light blue[2][3] |

| |

| |

| Use | Civil and state flag, civil and state ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | December 22, 1895 by pro-independence members of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico exiled in New York City; members identified colors as red, white, and blue but did not specify color shades; some historians have presumed members adopted light blue shade based on the light blue flag of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt[4] |

| Design | Five equal horizontal stripes, alternating from red to white, with a blue equilateral triangle based on the hoist side bearing a large, sharp, upright, five-pointed white star in the center; see specifications in Colors and Dimensions |

| Designed by | Disputed between Puerto Ricans Francisco Gonzalo Marín in 1895 and Antonio Vélez Alvarado in 1892; based on Cuban flag by Venezuelan Narciso López and Cuban Miguel Teurbe Tolón in 1849 |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Puerto Rico |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Topics |

| Symbols |

The flag of Puerto Rico (Spanish: Bandera de Puerto Rico), officially the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Spanish: Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit. 'Flag of the Free Associated State of Puerto Rico'),[1] represents Puerto Rico and its people. It consists of five equal horizontal stripes, alternating from red to white, with a blue equilateral triangle based on the hoist side bearing a large, sharp, upright, five-pointed white star in the center. The white star stands for the archipelago and island, the three sides of the triangle for the three branches of the government, the blue for the sky and coastal waters, the red for the blood shed by warriors, and the white for liberty, victory, and peace.[5] The flag is popularly known as the Monoestrellada (Monostarred), meaning having one star, a single star, or a lone star.[6][7] It is in the Stars and Stripes flag family.

In September 1868, the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico launched the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt against Spanish rule in the main island, carrying as their standard the Bandera del Grito de Lares (Grito de Lares Flag), commonly known as the bandera de Lares (Lares flag).[8] Marking the establishment of a national consciousness for the first time, it is recognized as the first flag of Puerto Rico.[9]

In December 1895, 27 years after the failed revolt in the municipality of Lares, members of the committee, in partnership with fellow Cuban rebels exiled in New York City, replaced the Lares flag with the current design as the new revolutionary flag to represent an independent Puerto Rico. Based on the flag of Cuba, the standard of the Cuban War of Independence against Spain, its adoption symbolized the strong bonds existing between Cuban and Puerto Rican revolutionaries and the united independence struggles of Cuba and Puerto Rico as the last two remaining territories of the Spanish Empire in the Americas since 1825.[10][11]

The Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico identified the colors of the flag as red, white, and blue but failed to specify any shade, leading to an ongoing debate about the tonality of the color blue.[12] Contemporaneous secondary oral sources claimed the light blue used on the Lares flag was retained.[4][13][11] However, there were several renditions of said flag made, with the only one authenticated by a written primary source featuring a dark blue.[14][15][16]

In March 1897, the flag was flown during the Intentona de Yauco (Attempted Coup of Yauco) revolt, the second and last assault against Spanish rule before the start of the invasion, occupation, and annexation of Puerto Rico by the U.S. during the Spanish-American War in July 1898.[17][18] The public display of the flag was outlawed throughout the first half of the 20th century.

In July 1952, it was adopted as the official flag of Puerto Rico with the establishment of the current political status of commonwealth, after several failed attempts were made by the insular elected government in the prior decades. The colors were identified as red, white, and blue by law, but the shades were not specified.[2][10][19] However, the newly formed administration of Governor Luis Muñoz Marín used a dark blue matching that of the American flag as the de facto shade.

In August 1995, a regulation confirmed the colors but did not specified any shade.[1] With its promulgation, medium blue began to be used by the people as the de facto shade, replacing dark blue. In August 2022, an amendment bill was unsuccessfully introduced in the Puerto Rican Senate which would have established the medium blue on the current flag, a so-called azul royal (royal blue), as the official shade.[20]

It is common to see the equilateral triangle of the flag with different shades of blue, as no specific one has been made official by law. Occasionally, the shade displayed is used to show preference on the issue of the political status, with light blue, presumably used by pro-independence rebels in 1868 and 1895, representing independence and sovereigntism, dark blue, widely used by the government since 1952, representing statehood, and medium blue, most commonly used by the people since the 1995, representing the current intermediary status of unincorporated territory.

The flag of Puerto Rico ranked seventh out of 72 entries in a poll regarding flags of subdivisions of the U.S. and Canada conducted by the North American Vexillological Association in 2001.[21]

History

First Spanish designs

Discovery

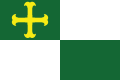

The introduction of a flag in Puerto Rico can be traced back to November 19, 1493 when Christopher Columbus landed on the island's shore, and with the flag appointed to him by the Spanish Crown, claimed the island, originally known by its native Taíno people as Borikén, in the name of Spain, calling it San Juan Bautista (Saint John Baptist) in honor of prophet John the Baptist, who baptized Jesus Christ. Columbus wrote in his logbook that on 12 October 1492 that his fleet carried the royal standard of the Crown of Castile, representing the Spanish Monarchy, and La Capitana, the captain’s expeditionary ensign featuring, on a white background, a green cross in the center and an 'F' and 'Y', both green and crowned with golden, open royal crowns, for Ferdinand II of Aragon and Ysabel, the Catholic Monarchs of a unified Spain.[22][23]

Colonization

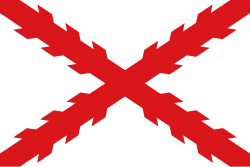

Conquistadores under the command of Juan Ponce de León, the first European explorer and governor of Puerto Rico, proceeded to conquer and settle the island in 1508, displacing, enslaving, and killing the native Taíno people. They carried the royal standard of the Crown of Castile, the emblem representing the Spanish Monarchy, and the Cross of Burgundy, the military standard representing the Spanish Empire, the latter of which continues to be flown on the Spanish-built fortifications in Puerto Rico, most notably on Castillo San Felipe del Morro and Castillo San Cristóbal.[24][25]

First Puerto Rican design

Revolutionary and Antillean origins

In 1868, Puerto Rican pro-independence leader Ramón Emeterio Betances, having gathered flag-making materials from Eduvigis Beauchamp Sterling, urged Mariana Bracetti to knit the revolutionary flag of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares), the standard of the first of two short-lived revolts against Spanish rule in the island, using as design the quartered flag of the First Dominican Republic, which was inspired by the Haitian and French flags, and based on the regimental flags of the Kingdom of France, and the lone star of the Cuban flag, which was inspired and based on the American flag. The fusion of the Dominican and Cuban flags to make the Puerto Rican Lares flag was aimed at promoting the union of neighboring Spanish-speaking Greater Antilles—the single-nation islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic in the two-nation island of Hispaniola—into an Antillean Confederation for the protection and preservation of their sovereignty and interests.[26][27][28]

In 1868, during the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt, Francisco Ramírez Medina, having been sworn in as Puerto Rico's first president by the revolutionaries, proclaimed the Lares flag as the national flag of the "Republic of Puerto Rico,” and placed it on the high altar of the San José Parish in Lares, Puerto Rico, making it the first Puerto Rican flag.[29]

Original flags

There were several flags made for the revolt, but only two have survived to this day. The oldest known Lares flag is quartered by a centered white cross, with two bottom red rectangles and two top light blue rectangles, the left of which bears a tiled, centered, five-pointed white star. According to anthropologist Ricardo Alegría, the flag was taken from the altar of the San José Parish of Lares by Spanish Captain José de Perignat, who kept it until his family donated it to Fordham University in New York City. In 1954, the university then gifted the flag to the Museum of History, Anthropology and Art of the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, then headed by Alegría, and in 1988, it was restored by the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.[13]

Since the early 20th century, some historians have questioned the authenticity of the flag, as there is no documentary evidence to validate that it was used in the revolt or that it was placed on the altar of the San José Parish in Lares, Puerto Rico.[15] It has been speculated that this flag is not an original Lares flag, but a copy made in the 1930s by nationalists for their commemoration of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt. Yet at the same time, other historians claim that, despite the absence of primary sources to validate the flag, there is a long oral tradition of testimonies that authenticate it.[30]

The recently discovered Lares flag is quartered by a centered white cross, with two red squares on the fly side and two dark blue squares on the hoist side, the top of which bears a tiled, centered, five-pointed white star. According to the Archivo Digital Nacional de Puerto Rico (ADNPR) (National Digital Archive of Puerto Rico), the flag, considered to be La Coronela (military flag), the most important flag that was used by the first company commanded by the colonel of the armies, was captured in 1868 by Spanish Captain Manuel Iturriaga, who led the repression of the revolutionaries of Lares, in the Piedra Gorda neighborhood of Camuy, Puerto Rico after it was discovered on the farm of a revolutionary buried in one of two wooden boxes alongside hundreds of cartridges for militia rifles. After Iturriaga’s death, the flag was donated by his son to the Museo de Artillería de España (Museum of Artillery of Spain). Since its discovery in 2022, the flag is exhibited at the Museo Del Ejército (Museum of the Army) in Toledo, Spain.[15][31]

In 1872, the flag was mentioned in Historia de la insurrección de Lares… (History of the insurrection of Lares…), a chronicle on the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) written by Spanish telegrapher and journalist José Manuel Pérez Moris, a contemporary who had migrated to Puerto Rico from Cuba in 1869.[16][32] Categorizing the flag as “la verdadera bandera de Lares” (“the real flag of Lares”), the Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe (CEAPRC) (Center of Advanced Studies of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean), claims that primary sources like Pérez Moris’ account of the revolt prove that this flag is the authentic one created by the revolutionary forces of the “Republic of Puerto Rico” that was to be born from the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt in 1868.[14]

Last Spanish designs

Provincial

In 1873, following the abdication of Amadeo I of Spain, and the overthrow of Monarchy for a Republic, the Spanish government issued a new flag for Puerto Rico. The provincial flag resembled the quartered Lares flag, with the difference that it featured the Spanish colors: all four squares in red, and the cross in yellow with the coat of arms of Puerto Rico in its center. The flags of Spain once more flew over Puerto Rico with the restoration of the Spanish kingdom in 1874, until 1898, the year that the island became a possession of the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1898) in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War.[33]

Military

Spanish-Puerto Ricans carried the war flag of the 3rd Battalion of Puerto Rico in the island, but most commonly in Cuba during the Cuban War of Independence against Spain between 1895 and 1898. The flag is in the shape and colors of the Spanish flag, with two equal red stripes on either side and a larger yellow stripe in the center, which contains the coat of arms of Spain with the text BATALLON PROVISIONAL DE PUERTO RICO N° 3 (PROVISIONAL BATTALION OF PUERTO RICO No. 3) around it. Puerto Rico and Cuba became possessions of the United States as a result of the Spanish-American War of 1898, thus ending more than 400 years of Spanish rule on both islands.

Current Puerto Rican design

Cuban and Puerto Rican solidarity

In December 1895, Juan de Mata Terreforte and other exiled Puerto Rican revolutionaries, many of them veterans of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt who fought alongside commander Manuel Rojas Luzardo, re-established the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico under the name Sección Puerto Rico del Partido Revolucionario Cubano (Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party) as part of the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York City, where they continued to advocate for Puerto Rican independence from Spain with the support of Cuban national hero José Martí and other Cuban exiles, who similarly began their struggle for self-determination in 1868 when the Grito de Yara (Cry of Yara) revolt triggered the Ten Years' War (Guerra de los Diez Años) for independence against Spanish rule in Cuba, which, along with Puerto Rico, represented all that remained from Spain’s once extensive American empire since 1825.

Revolutionaries from Cuba and Puerto Rico not only shared their exile in camaraderie and solidarity, but they also honorably fought and died together in battlefields across Cuba during the war of independence of the island, with approximately 2,000 Puerto Ricans falling in action, including Captain Francisco Gonzalo Marín Shaw. Puerto Ricans also made strategic contributions in battles led by Generals Juan Ríus Rivera and José Semidei Rodríguez, Colonels Juan Ortíz Quiñones and Epifanio Rivera, and dozens of other Puerto Rican officers and troops who served and fought in the Cuban Liberation Army.[34]

Revolutionary adoption

Determined to affirm the absolute union of the Cuban and Puerto Rican struggle for national independence into a single, common cause, on December 22, with the knowledge and approval of their fellow Cuban revolutionaries, Terreforte, vice-president of the committee, and forty-nine fellow members gathered at the no longer existent Chimney Corner Hall in Manhattan, unanimously adopted the Cuban flag with colors inverted as the new revolutionary flag to represent a sovereign “Republic of Puerto Rico”, replacing the Lares flag, which had been used by revolutionaries as the flag of a prospective independent Puerto Rico since their attempt at self-determination in 1868, but was eventually rejected, as it represented a failed revolt, a sentiment strongly supported by Lola Rodríguez de Tío, Puerto Rican poet, pro-independence leader, and committee member, who spent her later life exiled in liberated Cuba.[35][10][11]

Consecrated by the spilled blood of the thousands of Puerto Ricans who had fought and died in Cuba during the war of independence, the new flag was described by Bentances, Padre de la Patria (Father of the Homeland), as la sagrada bandera de la patria (the sacred flag of the homeland). Following not only Betances, but also national heroes Martí and Ruís Rivera, both of whom approved of the flag, pro-independence leaders from Puerto Rico, including Luis Muñoz Rivera, José De Diego, and Pedro Albizu Campos, revered the flag as a precious symbol representing the ideal of Patria y Libertad (Homeland and Liberty).[34][36]

In Acta Tercera (Third Act) of Memoria de los trabajos realizados por la Sección Puerto Rico del Partido Revolucionario Cubano, 1895–1998 (Memoir of the works accomplished by the Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, 1895–1898), a recollection on the activities of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico arranged by the Partido Revolucionario Cubano (Cuban Revolutionary Party), the unveiling of the new revolutionary Puerto Rican flag is described in Spanish as:

"Terreforte, uno de los supervivientes del Grito de Lares, presentó la nueva bandera que es de la misma forma que la Cubana, con la diferencia de haber sido invertidos los colores: franjas blancas y triángulo azul en vez de rojo, con la misma estrella blanca solitaria en el centro."

which, translated in English, reads as:

"Terreforte, one of the survivors of the Cry of Lares, presented the new flag that is in the same way as the Cuban one, with the difference that the colors have been inverted: white stripes and blue triangle instead of red, with the same lone white star in the center."

The flag is mentioned in Spanish for a second time in the same memoir under Memoria de la Sección Puerto Rico del Partido Revolucionario Cubano (Memoir of the Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party), an account written by Puerto Rican senior committee member Roberto H. Todd and endorsed by fellow member José Julio Henna, president of the committee, at the end of the functions of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee in 1898:

"Acordosé además por la Asamblea adoptar como bandera de Puerto Rico el mismo pabellón Cubano con los colores invertidos, esto es: listas blancas y rojas y el triángulo azul con la estrella solitaria blanca…"

which, translated in English, reads as:

"It was also agreed by the Assembly to adopt as the flag of Puerto Rico the same Cuban flag with the inverted colors, that is: white and red bands and the blue triangle with the white lone star..."

The name of the designer of the newly created Puerto Rican flag does not appear in the chronicle.

Disputed Puerto Rican designer

The origin of the design remains contested between exiled Puerto Rican revolutionaries Francisco Gonzalo Marín Shaw and Antonio Vélez Alvarado.[12]

Terreforte attributes the design to Marín Shaw, a member of the Cuban Liberation Army from Puerto Rico who died fighting for independence in Cuba in 1897. In May 1923, responding to a letter from fellow committee member Domingo Collazo asking him to clarify the origin of the design adopted in New York City after reading several different versions about its origin in the Puerto Rican newspapers, Terreforte, who presented the design to members of the committee in 1895, credits the idea of a design based on the Cuban flag with colors inverted to Francisco Gonzalo Marín.

The original response of Terreforte in Spanish reads as:

"La adopción de la bandera Cubana con los colores invertidos me fue sugerida por el insigne patriota Francisco Gonzalo Marín en una carta que me escribió desde Jamaica. Yo hice la proposición a los patriotas puertorriqueños que asistieron al mitin de Chimney Hall y fue aprobada unánimemente."

which, translated in English, reads as:

“The adoption of the Cuban flag with the colors inverted was suggested by the distinguished patriot Francisco Gonzalo Marín in a letter he wrote me from Jamaica. I made the proposition to Puerto Rican patriots who assisted the meeting at Chimney Hall and it was unanimously approved."

For its part, La Asociación Manatieña Amigos de la Bandera (Manatieña Association Friends of the Flag) credits fellow Manatieño Vélez Alvarado for the design based on the studies of Puerto Rican archeologist and historian Ovidio Dávila, most famously presented in El Centenario de la Adopción de la Bandera de Puerto Rico (The Centenary of the Adoption of the Flag of Puerto Rico) in 1996. According to the scholar, the origin of the flag’s design traces back to June 1892 when Vélez Alvarado suffered a momentary "optical illusion... as if by a 'rare color blindness,’ in which he perceived that the red triangle of the Cuban flag had turned blue and the blue stripes red."

Inspired by this experience, Vélez Alvarado created a new flag design for Puerto Rico. A few days later, according to Dávila, Vélez Alvarado presented his new design to Cuban pro-independence leader José Martí at dinner party attended by revolutionaries, including Marín Shaw. Martí, says Dávila, gave Vélez Alvarado his approval, and "soon after" he published in his newspaper, Patria, "a chronicle in which he emotionally described" the evening.[40] As such, the historian asserts that the flag of Puerto Rico was known to revolutionaries a couple of years before it was formally adopted in 1895.

Puerto Rican professor of history Armando Martí Carvajal has refuted Davila’s findings based on the fact that none of his sources are primary sources. Carvajal contends that Martí never actually confirmed any of the claims made by Davila, explaining that Martí did wrote on many occasions about the flag of Puerto Rico, but in these cases he was referring to the Lares flag, not to the new flag.[12]

Unlike Carvajal, Cuban professor Avelino Víctor Couceiro Rodríguez supports Dávila’s findings, citing as evidence the same secondary written accounts used by Dávila, including the assertions made by historian Cayetano Coll Toste and lawyer José Coll Cuchí, respected contemporaries who identified Vélez Alvarado as the original designer of the flag.[34]

In 1922, Coll Toste, the official historian of Puerto Rico between 1913 and 1927, wrote that it is said that the flag had been drawn by Antonio Vélez Alvarado.[41][34]

In 1923, lawyer José Coll Cuchí, son of Coll Toste, described the origins of the flag in El Nacionalismo en Puerto Rico (Nationalism in Puerto Rico) as follows:

"Y cuando allá por 1890 se agitaban cubanos y puertorriqueños en New York, formando Partidos Revolucionarios, el Sr. Antonio Vélez Alvarado, Vice-presidente del 'Club Borinquen', trazó la bandera de Puerto Rico, y ésta se hizo a semejanza de la de Cuba, invirtiendo los colores…Más tarde, en 1895…a organizar la primera expedición a Puerto Rico, se adoptó en solemne asamblea la bandera del triángulo azul, y que fue presentada a la Asamblea por José de Matta Terreforte…"

— José Coll Cuchí, 1923[34]

which, translated in English, reads as:

"And when back in 1890 Cubans and Puerto Ricans were agitated in New York, forming Revolutionary Parties, Mr. Antonio Vélez Alvarado, Vice-president of the 'Club Borinquen', drew the flag of Puerto Rico, and it was made like that of Cuba, inverting the colors…Later, in 1895…to organize the first expedition to Puerto Rico, the flag of the blue triangle was adopted in a solemn assembly, and it was presented to the Assembly by José de Matta Terreforte..."

— José Coll Cuchí, 1923[34]

As alluded by historians Dávila and Couceiro Rodríguez, followers of Vélez Alvarado believe that he was the victim of a discrediting campaign aimed at undermining his reputation as the original designer of the flag. Vélez Alvarado had been commonly recognized as the Padre de la Bandera Puertorriqueña (Father of the Puerto Rican Flag) since the 1890s, but his status as the creator of the flag began to be questioned in the 1930s, after he became one of the founding members of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico and main supporters of the violent and terrorizing pro-independence struggle advocated by militant leader Albizu Campos.[12]

Other historians have claimed that neither Marín Shaw or Vélez Alvarado designed the flag, attributing it instead to fellow Puerto Rican revolutionaries Manuel Besosa, whose daughter is claimed to have sown the flag presented at the adoption meeting, and Lola Rodríguez de Tió,[12] prominent pro-independence Puerto Rican poet who composed the first version of the national anthem of Puerto Rico, La Borinqueña, in 1868 as the rallying cry for the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt, and who famously wrote A Cuba (To Cuba), in which she describes in Spanish the intertwined independence struggles of the two islands and the strong interrelationships between their exiled revolutionaries as:[10][12]

“Cuba y Puerto Rico son

de un pájaro las dos alas,

reciben flores o balas

sobre el mismo corazón...”— Lola Rodríguez de Tió, 1893[42]

which, translated in English, reads as:

“Cuba and Puerto Rico are

As two wings of the same bird,

They receive flowers and bullets

Into the same heart...”— Lola Rodríguez de Tió, 1893[43]

First waving

The new revolutionary flag of Puerto Rico was first flown on the island in May 1896 during the funeral of pro-independence Puerto Rican leader and Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) veteran José Gualberto Padilla.[44][45] A year later, in 1897, Antonio Mattei Lluberas visited the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee in New York City to plan a revolt in the municipality of Yauco. He returned to Puerto Rico with the new revolutionary flag representing a prospective independent Puerto Rican republic. On March 24, 1897, a group of men led by Fidel Vélez and openly carrying the flag for the first time in Puerto Rico, unsuccessfully attacked the barracks of Spanish Civil Guard in Yauco. The Intentona de Yauco (Attempted Coup of Yauco) revolt was the second and last major attempt against Spanish rule in the island, which was invaded, occupied, and annexed by the U.S. during the Spanish-American War in July 1898.[46][47]

Outlawed display

As with the Lares flag, the use and display of this second revolutionary flag was outlawed, as the only flags permitted to be flown in colonial Puerto Rico were the Spanish flag (1493 to 1898) and the American flag (1898 to 1952). From December 10, 1898, the date of the annexation of Puerto Rico by the U.S., to July 25, 1852, the date of the establishment the commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Spanish: Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit. 'Free Associated State of Puerto Rico'), it was considered a felony to display the Puerto Rican flag in public, with the flag of the United States being the only flag permitted to be flown on the island.[48] However, the Puerto Rican flag was often used by the pro-independence Liberal Party of Puerto Rico and Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico at their assemblies.

In March 1948, the elected Puerto Rican Senate, controlled by the Partido Popular Democrático (PPD) and presided by Luis Muñoz Marín, who would become the first native Puerto Rican elected to colonial governorship in 1949 and the first governor of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico in 1952, approved the Gag Law 53 of 1948 (Ley de La Mordaza de 53 of 1948), which was signed into law in June by appointed governor Jesús T. Piñero, who became the first and only native Puerto Rican appointed to colonial governorship in 1946.

Similar to the anti-communist law passed in the U.S. in 1940, the Smith Act, which forbade any attempts to “advocate, abet, advise, or teach” the violent overthrow or destruction of the U.S. government, Puerto Rico’s gag law of 1948, made it a crime to own or display a Puerto Rican flag, to sing a patriotic tune, to speak or write of independence, or meet with anyone, or hold any assembly in favor of independence.[49] Carrying a sentence of up to ten years imprisonment, a fine of up to US $10,000 (equivalent to $131,000 in 2024), or both, the law aimed to discourage and suppress organized opposition against the elected American-allied government of Puerto Rico, specifically resistance from armed nationalist militant members of the radical pro-independence Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico, which in 1950, incited not only by the aforementioned gag order, but also by the approval of the creation of the commonwealth by U.S. Congress and President Truman with the passing of the Puerto Rico Federal Relations Act of 1950, executed a coordinated series of insurrectionist attacks, which included the attempted assassinations of elected governor Muñoz Marín at La Fortaleza in Old San Juan and President Truman at Blair House in Washington, D.C.[50][51]

In 1957, the gag law was ruled unconstitutional and was repealed on the basis that it violated freedom of speech within Article II of the Constitution of Puerto Rico and the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

Commonwealth adoption

After several failed attempts by the colonial elected government of Puerto Rico in 1916, 1922, 1927 and 1932 to formalize the revolutionary flag of 1895 as the flag of Puerto Rico, in July 1952, with the establishment of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Spanish: Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit. 'Free Associated State of Puerto Rico'), the elected governor Luis Muñoz Marín and legislature finally adopted the flag of 1895 as the island’s standard, proclaiming it the official flag of Puerto Rico in the Ley del 24 Julio de 1952 (Law of July 24, 1952) as follows:[10]

Law 1. Section 1. The flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico shall be the one traditionally known heretofourth as the Puerto Rican Flag and which is rectangular in form, with five alternate horizontal stripes, three red and two white, and having next to the staff a blue equilateral triangle with a white five-pointed star. On the vertical side this triangle stretches along the entire width of the flag.

Some interpreted the adoption of the flag as a deliberate ploy by Muñoz Marín to neutralize the pro-independence movement within his own party.[52] For nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos, having the flag represent the new American-allied government was a desecration, while the Puerto Rican Independence Party accused the government of "corrupting beloved symbols."[53]

In 1995, the flag was proclaimed again as the flag of Puerto Rico in the Regulation on the Use in Puerto Rico of the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico of August 3, 1995 (Spanish: Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico del 3 de Agosto de 1995):

Regulation 5282. Article 3, B. The flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is what has traditionally been known until now as the Puerto Rican flag. Its shape is rectangular, with horizontal stripes, alternating, three red and two white, and it has next to the staff a blue equilateral triangle with a white five-pointed star. This triangle, on the vertical side, covers the entire width of the flag.

Symbolism

First Puerto Rican design

Independence and Antillean confederation

In 1868, Puerto Rican pro-independence leader Ramón Emeterio Betances, urged Mariana Bracetti to knit the revolutionary flag of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares), the emblem of the first of two short-lived revolts against Spanish rule in the island, using as design the quartered flag of the First Dominican Republic and the lone star of the Cuban flag with the aim of promoting Betances’ idea of uniting the three neighboring Spanish-speaking Caribbean territories of Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic into an Antillean Confederation for the protection and preservation of their sovereignty and interests.

Colors

According to Puerto Rican poet Luis Lloréns Torres, the white cross stands for the yearning of homeland redemption, the red rectangles for the blood poured by the heroes of the revolt, and the white star for liberty and freedom.[54][55] It’s assumed that like the blue triangle of the revolutionary flag of 1895, the blue rectangles of the Lares flag stand for the sky and waters of the island.

Current Puerto Rican design

Cuban and Puerto Rican solidarity for independence

In December 1895, around fifty exiled Puerto Rican revolutionaries, many of them veterans of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt, re-established the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico under the name Sección Puerto Rico del Partido Revolucionario Cubano (Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party) as part of the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York City, where they continued to advocate for Puerto Rican independence from Spain with the support of their Cuban companions, including Cuban national hero José Martí.[35]

Determined to affirm the strong bonds existing between Cuban and Puerto Rican revolutionaries, and the union of Cuban and Puerto Rican struggles for national independence and fights against Spanish colonialism, the committee, with the knowledge and approval of their fellow Cuban revolutionaries, unanimously adopted the Cuban flag with colors inverted as the new revolutionary flag to represent a sovereign “Republic of Puerto Rico”, replacing the Lares flag, which had been used by revolutionaries as the flag of a prospective independent Puerto Rico since their attempt at self-determination in 1868, but was eventually rejected, as it represented a failed revolt.[10]

In Memoria de los trabajos realizados por la Sección Puerto Rico del Partido Revolucionario Cubano, 1895–1998 (Memoir of the work accomplished by the Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, 1895–1898), a memoir arranged by the Partido Revolucionario Cubano (Cuban Revolutionary Party) with a written account by members of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico Robert H. Todd and José Julio Henna, the new Puerto Rican flag is described as being the Cuban flag with inverted colors: white and red stripes and a blue triangle with a white star in the center.[12][37][38]

Consecrated by the spilled blood of the thousands of Puerto Ricans who had fought and died in Cuba during the war of independence, the new flag was described by Bentances, Padre de la Patria (Father of the Homeland), as la sagrada bandera de la patria (the sacred flag of the homeland). Following not only Betances, but also national heroes Martí and Ruís Rivera, both of whom approved of the flag, pro-independence leaders from Puerto Rico, including Luis Muñoz Rivera, José De Diego, and Pedro Albizu Campos, revered the flag as a precious symbol representing the ideal of Patria y Libertad (Homeland and Liberty).[56]

Revolutionary colors

There is no direct written account by members of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee specially detailing the symbolism of the colors of the flag adopted in 1895. However, according to some historians, the committee proclaimed that the blue triangle stands for the sky and coastal waters, the three red stripes for the spilled blood of brave warriors, the two white stripes for victory and peace after gaining independence, and the white star for the island of Puerto Rico.[5][57] In the absence of a direct explanation from the committee members, other historians have concluded that like the Cuban flag, the three colors of the flag and the three points of the triangle represent the republican ideals of freedom, equality, and fraternity proclaimed in the French Revolution.[10]

Form of government and colors for the commonwealth

In August 1995, the commonwealth government of Puerto Rico, in accordance with the Ley del 24 Julio de 1952 (Law of July 24, 1952), which stipulated the adoption of the flag of 1895 as the official flag of Puerto Rico, issued a regulation regarding the use of the flag titled Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico (Regulation on the Use in Puerto Rico of the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico), in which it defined the symbolism in Spanish as:

Regulación 5282. Artículo 3, C. La estrella es símbolo del Estado Libre Asociado y reposa sobre un triángulo azul que en sus tres ángulos evoca la integridad de la forma republicana de gobierno representada por tres poderes: el legislativo, el ejecutivo y el judicial.

Las tres franjas rojas simbolizan la sangre vital que nutre a esos tres poderes de Gobierno, los cuales desempeñan funciones independientes y separadas. La libertad del individuo y los derechos del hombre mantienen en equilibrio a los poderes y su misión esencial la representan dos franjas blancas.

which, translated in English, reads as:

Regulation 5282. Article 3, C. The star is symbol of the Commonwealth and rests on a blue triangle that in its three angles evokes the integrity of the republican form of government represented by three powers: the legislative, the executive and the judicial.

The three red stripes symbolize the vital blood that nourishes those three governing powers, which perform independent and separate functions. The freedom of the individual and the rights of men keep the powers in balance and their essential mission is represented by two white stripes.

The original symbolism of the flag, said to have been described by the pro-independence Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee in 1895, is different from the one believed to have been in place since 1952 but only officially stipulated in the regulation of 1995. Whereas the original alludes to the revolutionary roots of the flag with references to “brave warriors” and “gaining independence,” the latest not only implies the dignity and nobility of the established commonwealth government that adopted and retains the flag with references to “integrity,” “freedom,” “rights of men,” and “balance,” but it also implicates adherence and allegiance to said government when it mentions “the vital blood that nourishes those three governing powers.”

Pride

Korean War

Among the many occasions in which the flag has been used as a symbol of pride was when the flag arrived in South Korea during the Korean War. On August 13, 1952, while the men of Puerto Rico's 65th Infantry Regiment (United States) were being attacked by enemy forces on Hill 346, the regiment unfurled the flag of Puerto Rico for the first time in history in a foreign combat zone. During the ceremony Regimental Chaplain Daniel Wilson stated the following:[58][59]

"Grant us Thy Peace and Power in this conflict against aggression and tyranny. Show us in Thy purpose Peace for all the men in the world. We dedicate this flag of the Associated Free State of Puerto Rico in Thy name."

The Commanding Officer Colonel Juan César Cordero Dávila was quoted saying the following:[58][59]

"How beautiful is our flag, how it looks next to the stars and the stripes! Let the communists on the other side of the Yokkok River see it and listen to me those who understand Spanish if these words reach your trenches."

Space

On March 15, 2009, several Puerto Rican flags were aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery during its flight into outer space. Joseph M. Acabá, Puerto Rican astronaut who was assigned to the crew of STS-119 as a Mission Specialist Educator, carried on his person the flag as a symbol of his Puerto Rican heritage.[60] Acabá presented the 185th Governor Luis Fortuño and Secretary of State Kenneth McClintock with two of the flags during his visit in June 2009.[61][60][62]

Music

The flag is also the subject of the well-known song "Qué Bonita Bandera" ("What a Beautiful Flag") written in 1968 and made popular by Puerto Rican folksinger Florencio "Ramito" Morales Ramos. Astronaut Acabá requested that the crew be awakened on March 19, 2009 (Day 5 in space), with this song, as performed by José González and Banda Criolla. In 2012, Plena and Bomba Puerto Rican singing group, Plena Libre, released a modern rendition of the song.[63]

Protest

Nationalist attack at U.S. Capitol

On various occasions the flag has been used as a symbol of protest, defiance, or terror. In the 1954 armed attack of the United States House of Representatives, a violent, terrorizing protest against American rule of the island, Puerto Rican nationalist leader Lolita Lebrón and three other fellow members of Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico unfurled the flag of Puerto Rico as they shouted "¡Viva Puerto Rico Libre!" ("Long live Free Puerto Rico!").[64]

Statue of Liberty for Vieques

On November 5, 2000, Alberto De Jesús Mercado, known as Tito Kayak, and five other activists, protesting against the use of the island of Vieques as a bombing range by United States Navy, stepped onto the top deck of the Statue of Liberty in New York City and placed a large Puerto Rican flag on the statue's forehead, reenacting an earlier protest carried out on October 25, 1977 by Puerto Rican nationalists, who were demanding the release of four fellow nationalists serving time for their armed attack of the United States House of Representatives in 1954.[65]

Dimensions

Law

In the law of Puerto Rico, the only two mentions of the dimensions of the flag are found in the Ley del 24 Julio de 1952 (Law of July 24, 1952):

Law 1. Section 1. The flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico shall be the one traditionally known heretofourth as the Puerto Rican Flag, and which is rectangular in form, with five alternate horizontal stripes, three red and two white, and having next to the staff a blue equilateral triangle with a white five-pointed star. On the vertical side this triangle stretches along the entire width of the flag.

and in the Regulation on the Use in Puerto Rico of the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico of August 3, 1995 (Spanish: Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico del 3 de Agosto de 1895):

Regulation 5282. Article 3, B. The flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is what has traditionally been known until now as the Puerto Rican flag. Its shape is rectangular, with horizontal stripes, alternating, three red and two white, and it has next to the staff a blue equilateral triangle with a white five-pointed star. This triangle, on the vertical side, covers the entire width of the flag.

Composition

Both documents describe the basic design of the flag, but do not provide exact dimensions on the size of its rectangular shape, horizontal stripes, and upright five-pointed star. While the exact proportions of the flag have not been established by law, the most commonly used and accepted layout of the flag is as follows:

At a length-to-width ratio of 2:3, the shape of the flag is rectangular, one and a half times longer than wide, composed of five alternating horizontal stripes, three red and two white, each one being one-fifth of the flag width, and an equilateral blue triangle on the hoist side vertically covering the entire width of the flag and bearing a large, sharp, upright, centered, five-pointed white star of which diameter is at least one-third and at most half of the flag width.

Most representations of the flag follow these specifications, with the only component likely to vary being the star, which is not unusual to be displayed bigger than the most commonly used sizes of one-third (1⁄3) and two-fifths (2⁄5) of the flag width.

Colors

Law

In the law of Puerto Rico, the only two mentions of the colors of the flag are found in the Ley del 24 Julio de 1952 (Law of July 24, 1952):

Law 1. Section 1. The flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico shall be the one traditionally known heretofourth as the Puerto Rican Flag, and which is rectangular in form, with five alternate horizontal stripes, three red and two white, and having next to the staff a blue equilateral triangle with a white five-pointed star. On the vertical side this triangle stretches along the entire width of the flag.

and in the Regulation on the Use in Puerto Rico of the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico of August 3, 1995 (Spanish: Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico del 3 de Agosto de 1895):

Regulation 5282. Article 3, B. The flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is what has traditionally been known until now as the Puerto Rican flag. Its shape is rectangular, with horizontal stripes, alternating, three red and two white, and it has next to the staff a blue equilateral triangle with a white five-pointed star. This triangle, on the vertical side, covers the entire width of the flag.

Color schemes

Both documents describe the flag as having “red” and “white” alternating horizontal stripes, a “blue” equilateral triangle, and a “white” five-pointed lone star, but do not specify any official color shades. While the exact colors of the Puerto Rican flag have not been established by law, below are the most commonly used color shades. The intensity of both blue and red color shades changes to keep them complementary to each other.

Current medium blue flag

Medium blue, or royal blue, flag of Puerto Rico (1995) uses the following color shades:

Colors scheme | Blue | Red | White |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | 8,68,255 | 237,0,0 | 255-255-255 |

| Hexadecimal | #0044ff | #ed0000 | #ffffff |

| CMYK | 100-73-0-0 | 0-100-100-7 | 0-0-0-0 |

| Pantone | 2387 C | 2347 C | 11-0601 TX Bright White |

Dark blue flag

Dark blue, or navy blue, flag of Puerto Rico (1952), matching the colors of the dark blue original Lares flag, one of two original versions of the flag available today, uses the following color shades:

Colors scheme | Blue | Red | White |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | 0,56,167 | 206,17,39 | 255-255-255 |

| Hexadecimal | #0038a7 | #ce1127 | #ffffff |

| CMYK | 100-66-0-35 | 0-92-81-19 | 0-0-0-0 |

| Pantone | 293 C | 186 C | 11-0601 TX Bright White |

Light blue flag

The light blue flag of Puerto Rico has become increasingly popular in recent years. Today, most representations of the flag feature a light sky blue color shade, matching the light blue color shade of one of only two original renditions of the first revolutionary flag of Puerto Rico, the Lares flag.

Light blue, or sky blue, flag of Puerto Rico (1895), matching the colors of the light blue Lares flag, which is one of two original versions of the flag available today, uses the following color shades:

Colors scheme | Blue | Red | White |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | 135-206-250 | 206-0-0 | 255-255-255 |

| Hexadecimal | #87cefa | #Ce0000 | #ffffff |

| CMYK | 46-18-0-2 | 0-100-100-19 | 0-0-0-0 |

| Pantone | 2905 U | 3517 C | 11-0601 TX Bright White |

Blue shade

Original colors

In 1898, the first two descriptions of the design of the flag of Puerto Rico appeared in Memoria de los trabajos realizados por la Sección Puerto Rico del Partido Revolucionario Cubano, 1895–1998 (Memoir of the work accomplished by the Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, 1895–1898), a recollection on the activities of the committee arranged by the Cuban Revolutionary Party, in which not only a list of the acts carried out by the Puerto Rican committee is provided by the Cuban party, but also an account of the committee’s actions written by Robert H. Todd, senior committee member, and endorsed by José Julio Henna, president of the committee, both of whom where present at the adoption of the flag in New York City in 1895, is included.[12][37][38]

Both mentions of the flag in the memoir describe it as being the Cuban flag with inverted colors, identifying its alternating stripes as “red” and “white,” triangle as “blue,” and lone star as “white.” The color shades were not specified in the memoir, but it includes the revolutionary coat of arms of the committee, which features the flag of Puerto Rico in black and white with a dark equilateral triangle, possibly indicating the use of a dark shade of blue.

Dark blue

The only original flag of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt authenticated by a written primary source is the one mentioned in Historia de la insurrección de Lares (History of the Lares insurrection), written by José Pérez Moris in 1872.[16][32] Currently exhibited in the Museum of the Army in Toledo, Spain, the flag features a dark blue shade. It appears that most flags displayed in Puerto Rico during the first half of the 20th century featured a dark blue, including one used in the manifestations that resulted in the Ponce Massacre of 1937.[66]

In 1952, when the newly established, elected commonwealth government adopted the revolutionary flag of 1895 as the island’s official standard, it identified by law its horizontal stripes as “red” and “white,” triangle as “blue,” and lone star as “white,” but it did not specify any official color shades. However, Luis Muñoz Marín, the architect and first governor of the commonwealth, and his administration, used a dark shade of blue, most commonly known as navy blue (Spanish: azul marino), matching that of the American flag, establishing it as the de facto shade.[2]

Some historians have argued that the dark blue unveiled by the American-allied commonwealth government in 1952 was deliberately chosen to distance the flag from its pro-independence revolutionary originators, who are claimed to have used light blue for the Lares flag in 1868 and the current flag in 1895, and link it to the similarly striped American flag through a shared shade of blue, with the aim of conveying a message of harmony between Puerto Rico and the U.S. Others have argued that the use of an American-derived dark blue instead of a medium or light blue arose from practical and economical needs, as it was the shade most widely and readily available.[4]

Medium blue

One of the oldest known color depictions of the revolutionary flag of 1895, appearing on a postcard in circulation between 1910 and 1920, features a medium shade of blue.[67]

In 1995, the commonwealth government of Puerto Rico issued a regulation regarding the use of the flag, Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico (Regulation on the Use in Puerto Rico of the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, in which it once again identified the flag as having red, and white horizontal stripes, a blue triangle, and a white lone star but did not specify any official color shade.[1] Since the regulation’s promulgation, the people have most commonly used a medium blue shade, widely known as royal blue (Spanish: azul real), as the de facto shade of blue. This shade has replaced dark blue as the most used color.

In August 2022, an amendment bill was unsuccessfully introduced in the Puerto Rican Senate which would have established the current medium blue, a so-called “azul royal” (royal blue), as the official color of the flag.[20]

Light blue

In early 2000s, a selected group of Puerto Rican historians gathered at the Ateneo Puertorriqueño (Puerto Rican Athenaeum), one of the island’s principal cultural institutions, proclaimed light blue, most commonly known as sky blue (Spanish: azul celeste), as the original shade of blue adopted by members of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico in 1895, citing as evidence contemporaneous but secondary oral sources identifying light blue as the original color shade, which their sources claim was the same shade used on the Lares flag, the revolutionary flag many of said same members rallied around during the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt in 1868.[4]

However, the original color shades used for the Lares flag remain unclear. It appears that only two of several flags made for the revolt in 1868 have survived to this day. The originality of the light blue flag of the revolt is in dispute, as there is no written primary source to authenticate it, with most historians recognizing it as a copy made by the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico in the 1930s based on contemporaneous but secondary oral sources.[13][30] The dark blue flag of the revolt is mentioned in Historia de la insurrección de Lares (History of the Lares insurrection), a written primary source from 1872 by José Pérez Moris that authenticates its originality.[16][32]

Cuban blue

Some historians have added that the shade of blue originally adopted in 1895 was light to medium blue, as that was the contemporaneous shade of the stripes of the Cuban flag during the Cuban War of Independence. However, there is disagreement among historians as to what was the original shade of blue of the Cuban flag, with some claiming it was light blue, while others say it was the current ”azul turquí” (navy blue), which is based on the navy blue of the American and French flags, the flags of the two countries which republican political revolutions in the late 18th century inspired in great part the Latin American independence movements of the 19th century, starting with Haiti in 1791.[12]

Current status

In August 2022, an amendment bill was unsuccessfully introduced in the Puerto Rican Senate which would have established the current medium blue, identified in the legislation as “azul royal” (royal blue), as the official shade.[20] Recognizing the royal blue as the most used throughout time, the bill aimed to declare it the formal shade to settle the uncertainty and debate that has persisted in Puerto Rico due to a lack of specificity in Ley del 24 Julio de 1952 (Law of July 24, 1952), the law that formally established the standard as the official flag. According to the bill, the ongoing issue over the tonality of the color blue has the international community confused as to what is the correct shade of blue to be used on the flag representing Puerto Rico abroad.

To this day, the color shades of the flag of Puerto Rico have never been officially determined by law in Puerto Rico. Therefore, it is common to see the triangle of the flag with different color shades of blue, ranging from the lighter sky blues to the medium azure blues and darker navy blues. Occasionally, the shade of blue displayed on the flag is used to show preference on the issue of the political status, with light blue, the shade presumably used by pro-independence revolutionaries in 1868 and 1895, representing complete independence from the U.S. and sovereigntism or independence as a sovereign freely associated state with the U.S., dark blue, the shade widely used by government since 1952, representing statehood or integration into the U.S. as a state, and medium blue, the shade in-between pro-independence light blue and pro-statehood dark blue most commonly used by the people since the 1990s, representing the current intermediary status of unincorporated and organized territory of the U.S.

Salute

Protocol

According to the law of Puerto Rico,[1] all people present when the flag is raised, lowered, or passed in a parade, must stand up, look at the flag, and stay as such until it is completely raised, lowered, or carried away in passing. Men must take off their hat, and hold it with their right hand placed near the left shoulder with the right hand on the heart. Men without a hat and women must greet the flag by putting their right hand on the heart. The personnel of the armed forces must greet militarily.

The official salute to the flag must be recited on the following occasions:

• In those official and civic activities that, due to their character, warrant it.

• In any act of an official or civic nature in which the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag of the United States is recited.

• On those occasions when the Governor of Puerto Rico so determines.

• The official salute to the flag must be recited after the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag of the United States.

Text

The text of the official salute to the flag of Puerto Rico is as follows:

| Spanish | English |

|---|---|

| Juro ante la bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, honrar la patria que simboliza, el pueblo que representa y a los ideales que encarna de libertad, justicia y dignidad. (Con la mano derecha sobre el corazón) | I swear before the flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, to honor the homeland it symbolizes, the people it represents, and the ideals it embodies of freedom, justice, and dignity. (With the right hand over the heart) |

| Regulation on the Use in Puerto Rico of the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico of August 3, 1995[1] | |

Protocol

The use of flag of Puerto Rico is regulated by Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico del 3 de Agosto de 1995 (Regulation on the Use in Puerto Rico of the Flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico of August 3, 1995).[1] The regulation stipulates the proper use of the flag from the fourth to the twenty-eighth article, which are as follows:

Outdoor use

• When the flag is raised outdoors, a flagpole must be used which length is no less than two and a half times the length of the flag.

• The flag must not be raised outdoors before sunrise or after sunset, except on those occasions when, for special reasons, the Governor of Puerto Rico provides otherwise. The flag may be hoisted at night on special occasions to produce a patriotic effect.

Where and when it should be hoisted

• If weather conditions allow it, the flag must be raised in or near public buildings during working days and in those commemorative activities of the following holidays:

| Holiday | Date |

|---|---|

| New Year’s Day | January 1st |

| Three Kings Day | January 6th |

| Eugenio María de Hostos Day | Second Monday of January |

| Martin Luther King Day | Third Monday of January |

| Presidents’ Day | Third Monday of February |

| Abolition of Slavery in Puerto Rico | March 22nd |

| José de Diego Day | Third Monday of April |

| Memorial Day | Last Monday of May |

| Independence of the United States | July 4th |

| Luis Muñoz Rivera Day | Third Monday of July |

| Constitution Day of Puerto Rico | July 25th |

| José Celso Barbosa Day | Fourth Monday of July, except in years when the celebration coincides with another holiday, in which case it will be observed on July 27th |

| Labor Day | First Monday of September |

| Columbus Day | October 12th |

| Veterans Day | November 11th |

| Discovery of Puerto Rico | November 19th |

| Thanksgiving | Fourth Thursday of November |

| Christmas | December 25th |

Note: Good Friday is not considered a public holiday.

• The flag must be hoisted in or near the premises intended for voting during the days of general or special elections.

• During the school season, the flag must be raised on or near the schools.

• The flag may be raised in the private residence of any citizen who so wishes.

• Flags may be hoisted by private institutions, as long as they comply with the provisions of this title.

How to fly the flag

• When raised next to flags of another nations, all flags and flagpoles must be equal in size and height.

• The flag must be raised speedily, but in a considerate, ceremonial, and respectful manner.

• The flag must be raised on a flagpole next to the flagpole where the flag of the United States has been raised. Both flags should be at the same height. The flag must be hoisted after the flag of the United States is hoisted, and it should be lowered before the flag of the United States is lowered. When the flag is raised, it should always be to the left of the flag of the United States, and no other flag will be placed between the two.

• The Flag must begin to be hoisted at the first note of the anthem of Puerto Rico and will continue to be raised until it reaches the top of the flagpole with the last notes of the anthem. This must also be done, but in reverse order, when the flag is lowered to the chords of the Anthem of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

• The flag must not be displayed with the upper tip of its five-pointed star down except in cases of emergency, such as in boats that are adrift or in serious danger of sinking, as this is the traditional naval way of asking for help.

In parade

• When the flag is carried in a parade, it must always be carried to the left of the flag of the United States, taking care that both are kept at the same height and at the same angle.

• Any other flag, banner, or emblem of state, municipal or private agencies that is also carried in the parade, must be carried immediately behind the flags, or to the left of them.

• When a flagpole is used to carry the flag, it must measure at least one and a half times the length of the flag.

• The flag must not be tilted when hymns of other nations are played or when the flags of other nations are displayed.

In a vehicle

• The flag must not be displayed on the hood, roof, sides, or back of a vehicle, be it a car, train, or any other transport vehicle.

• When the flag is displayed on a vehicle, a flagpole firmly secured to it must be used.

Display next to the flag of the United States and that of other nations

• When the flag, the flag of the United States, and that of any foreign nation or nations are displayed at the same time, all flags must be of the same size and must be hoisted on separate flagpoles of equal height.

• The flag must be to the left of the flag of the United States. The foreign flag or flags will be placed to the left of the flag of Puerto Rico, following the alphabetical order in Spanish of the countries they represent.

• In the case of the flags of Latin American nations, they will be placed in the alphabetical order of countries used by the Organization of American States, according to its Manual of Inter-American Conferences. This is: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Ecuador, El Salvador, United States, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Dominican Republic, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad-Tobago, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Display in the front of a building

• When the flag is hoisted on the front of a building, be it on the sill of a window or balcony, the blue equilateral triangle must be at the top of the flagpole unless the flag is hoisted at half-mast.

Display without a flagpole

• The flag must be displayed extended flat, either vertically or horizontally, falling freely and without folds. When displayed horizontally, the blue equilateral triangle must be to the right of the flag, that is, to the left of the observer in front of it.

On a street

• When displayed on a street, the flag must be suspended vertically with the base of the blue equilateral triangle facing up.

Use in public tribunes

• In the public grandstand, the flag should never be hoisted for decorative purposes or to cover the stand.

• When it is raised in front of a public tribune or platform, it must be placed at a higher level than that occupied by the speaker.

• When it is held on a public tribune together with that of the United States, the flag must be to the left of the speaker, and the flag of the United States to the right of the speaker.

Unveiling of statues or monuments

• The flag must be hoisted in all official ceremonies of unveiling statues or public monuments honoring the memory of illustrious people, but it should never be used to cover the statue or monument that is going to be unveiled.

Puerto Rico National Guard

• The flag must be displayed at all ceremonies or stops in which the National Guard participates.

In coffins alone

• When the flag is used to cover a coffin, it must be placed in such a way that the blue equilateral triangle is in the head end. The flag must be five feet by nine and a half feet. The flag must not descend to the grave, nor should it touch the earth.

In coffins next to the flag of the United States

• When the flag and that of the United States are used to cover a coffin, the flag of the United States will first be placed on the coffin so that the union or blue field of that flag is at the head to the left side of the coffin. The flag of Puerto Rico will be placed on the coffin, with the triangle towards the feet of the coffin with the apex of the triangle pointing towards the head.

In the presence of the Governor

• The flag will be raised or displayed at all public ceremonies in which the Governor of Puerto Rico is present.

Horizontal on the wall with the flag of the United States

• If the flag is placed horizontally on the wall, its colors must be completely displayed, with the triangle towards the right of it, that is, to the left of the person who observes it from the front. The flag will go to the left of the flag of the United States, that is, to the right of the observer.

Crossed on the wall with the flag of the United States

• When the flag of the United States and the flag of Puerto Rico are crossed against a wall, flagpole, or other place, the flag of Puerto Rico will be to the left of the flag of the United States. The flagpole of the United States, in accordance with its regulations, will be crossed over the flagpole of Puerto Rico. When looking at the flags thus arranged, the flag of the United States will be to the left of the observer, and that of Puerto Rico to the right of the observer.

Use at half-mast

• On the occasion when the flag must be raised at half-mast, it must first be hoisted to the top of the pole and then lowered to the half-mast position. When the flag is to be lowered from the half-mast position, it must first be raised to the top, and then be completely lowered.

• The use of black crepes on the flagpole is prohibited unless it is by order of the Governor of Puerto Rico.

• The flag must be hoisted at half-mast whenever the flag of the United States is hoisted at half-mast by presidential order.

• The flag must also be raised at half-mast when authorized or ordered by the Governor of Puerto Rico, by proclamation or executive order. In this case, the flag of the United States will also be hoisted at half-mast.

When folding the flag

• The flag must be folded following the military system accustomed to the flag of the United States, that is, in the form of a triangle. The folds will be made so that the star in the triangle of the flag is shown at the top of it, once folded.

Salute

• During the ceremony of hoisting or lowing the flag, or when it passes in a parade, all the people present must stand up, look at the flag and stay that way until it passes. Men must take off their hat and hold it with their right hand placed near the left shoulder so that the right hand is on the heart. Men without a hat and women will greet the flag by putting their right hand on the heart. The personnel of the armed forces will greet militarily.

Official salute to the flag

• The text of the Official salute to the flag of Puerto Rico will be as follows: I swear before the flag of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, to honor the homeland it symbolizes, the people it represents, and the ideals it embodies of freedom, justice, and dignity.

• The official salute to the flag must be recited on the following occasions:

• In those official and civic activities that, due to their character, warrant it.

• In any act of an official or civic nature in which the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag of the United States is recited.

• On those occasions when the Governor of Puerto Rico so determines.

• The official salute to the flag must be recited after the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag of the United States.

Respectful treatment

• No person shall mutilate, damage, desecrate, trample, insult or belittle with words or works the flag.

• The flag should not be allowed to touch the ground or the floor, or to crawl through the water.

• Nor should it be held, unfolded, used or stored in such a way that it is torn, stained, or easily exposed to damage.

• The flag should not be used to cover the ceiling or the roof of a place.

• When the conditions of the flag are such that it can no longer be used, it must be destroyed in private, respectful way, preferably through incineration.

• For no reason should a flag in a state of deterioration be used, that is, frayed or with faded colors.

• In cases where it is absolutely necessary to wash the flag, such washing must be done privately and in a respectful manner.

• In sporting events that take place in Puerto Rico, it will be the responsibility of the organizers of the activity and/or the administrators of the premises, to ensure at all times that due decorum and respect for the flags are given.

Prohibitions

• The flag must not be weaved or embroidered on cushions, handkerchiefs or similar items; nor should it be printed or engraved on napkins, whether of any material, or in boxes, or in any item that must be disposed of as unusable.

• The use of the flag as an emblem or badge of political parties or candidates listed on the ballot is prohibited.

• It is also forbidden to use it as an emblem or badge in relation to primary elections, plebiscite elections, referendum, or any other type of consultation that is made to the people by electoral means.

• The following practices are prohibited:

• Stamp, print or in any way make appear any word or words, number, mark, engraving, design, or advertisement of any kind on the flag.

• Unfold, or display in public view a flag on which a word, number, mark, engraving, design, painting, or advertisement of any kind has been printed, printed or added.

• Unfold to the public, sell, offer for sale or use any item or object that serves as a packaging for merchandise, in which the flag has been printed, printed, engraved or fixed in order to draw attention, decorate, mark or distinguish the item or object on which the flag has been printed, painted, fixed or stamped.

• No person shall use the flag in any type of commercial propaganda or for the purpose of attracting the attention of the consumer.

• The flag will not be used as part of, nor will it be printed on a suit, uniform, or dress, under any circumstances.

• It is forbidden to use the flag to cover, cover, dress or decorate animals, athletes or participants in public shows.

Exceptions to prohibitions

• The prohibitions will not be applicable to the press, nor to books, brochures, certificates, diplomas, appointments to public office, notebooks, jewelry or stationery for correspondence, in which the flag is printed, painted or stamped, detached from advertisements of all kinds.

Historical flags

The historical progression of flags in Puerto Rico is as follows:

| Historical Progression of Flags in Puerto Rico | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Flag | Name | Date | Use |

| Captain's Ensign of Christopher Columbus | 1493 | La Capitana expeditionary flag of Christopher Columbus carried by his fleet when the island of present-day Puerto Rico, known to its native Taíno people as Borikén, was claimed by Spaniards as San Juan Bautista (Saint John Baptist) during the second voyage of Columbus on 19 November 1493. The letter "F" represents King Ferdinand and the "Y" represents the Spanish rendering for Queen Isabella, the Catholic Monarchs of a unified Spain. |

| Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile | 1493–1715 | Royal emblem of the Crown of Castile, representing the Spanish Crown, flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico since its discovery as San Juan Bautista (Saint John Baptist) through the administrative division of the Captaincy General of Puerto Rico. |

| Flag of Cross of Burgundy | 1506–1898 | Military ensign of the Spanish Empire, used in the island of present-day Puerto Rico since its colonization as San Juan Bautista (Saint John Baptist) by Juan Ponce de León through the administrative division of the Captaincy General of Puerto Rico. The banner continues to be flown on the fortresses of Castillo San Felipe del Morro and Castillo San Cristóbal. |

| Flag of Spain | 1785–1873, 1874–1898 | Naval ensign and national flag of Spain flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico during the administrative divisions of the Captaincy General of Puerto Rico and the Province of Puerto Rico. |

| Flag of Grito de Lares | 1868 | Revolutionary standard of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt carried by members and followers of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico, who proclaimed it as the national flag of a prospective independent Puerto Rico. Lacking authentication from a written primary source, the originality of flag is disputed, with most historians identifying as a copy made in the 1930s by the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico based on secondary, oral sources. |

| Flag of Grito de Lares | 1868 | Revolutionary standard of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt carried by members and followers of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico, who proclaimed it as the national flag of a prospective independent Puerto Rico. Mentioned in 1872 by a written primary source, the originality of the flag is authenticated. |

| Flag of the First Spanish Republic | 1873–1874 | National flag of Spain, representing the country as a federal republic, flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico during the administrative division of the Province of Puerto Rico. |

| Flag of the Province of Puerto Rico | 1873–1874 | Provincial flag of the island of present-day Puerto Rico during the administrative division of the Province of Puerto Rico. |

| Flag of Intentona de Yauco | 1897–present | Revolutionary standard of the Intentona de Yauco (Attempted Coup of Yauco) revolt carried by members and followers of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico, who proclaimed it as the national flag of a prospective independent Puerto Rico in 1895, replacing the Lares flag. The original shade of blue of the flag remains in dispute, as there is no written primary source specifying it. Relying on contemporaneous secondary, oral sources, some historians have identified its shade of blue as light blue, as they claim that was the shade used on the Lares flag. However, there is no written primary source account specifying the original color shade of blue used on the Lares flag, the only two surviving original renditions of which feature different color shades of blue: one uses light blue and the other dark blue. One of the oldest depictions of the flag in the early 1900s features a medium blue shade. |

| Flag of the 3rd Battalion of Puerto Rico | 1898 | War flag of the 3rd Battalion of Puerto Rico flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico, but most commonly in Cuba by Spanish-Puerto Rican soldiers during the Cuban War of Independence against Spain between 1895 and 1898. Puerto Rico and Cuba became possessions of the United States as a result of the Spanish-American War of 1898, thus ending more than 400 years of Spanish rule on both islands. |

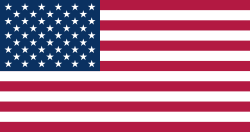

| Flag of the United States | 1898–1908 | National flag of the United States flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico as the Province of Puerto Rico during its invasion and occupation in the Spanish-American War, and its annexation as an American overseas territory through the Treaty of Paris, starting under a military government from 1898 to 1900 and continuing under an insular government from 1900 to 1952, which oversaw the establishment of a civil government and American nationality through the Foraker Act of 1900, and the expansion of the civil government and the establishment of American citizenship through the Jones-Sheffield Act of 1917. The flag features 45 stars, representing the 45 states of the American union at the time. |

| Flag of the United States | 1908–1912 | National flag of the United States flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico as an American overseas territory under an insular government from 1900 to 1952, which oversaw the establishment of a civil government and American nationality through the Foraker Act of 1900, and the expansion of the civil government and the establishment of American citizenship through the Jones-Sheffield Act of 1917. The flag features 46 stars, representing the 46 states of the American union at the time. |

| Flag of the United States | 1912–1959 | National flag of the United States flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico as an American overseas territory under an insular government from 1900 to 1952, which oversaw the establishment of a civil government and American nationality through the Foraker Act of 1900, and the expansion of the civil government and the establishment of American citizenship through the Jones-Sheffield Act of 1917. The flag features 48 stars, representing the 48 states of the American union at the time. |

| Flag of Puerto Rico | 1952–present | Subnational flag of Puerto Rico flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico as an unincorporated and organized American territory with autonomous local, democratic government, officially named the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Spanish: Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit. 'Free Associated State of Puerto Rico') upon its establishment in 1952. With its proclamation as the flag of the commonwealth through the Ley del 24 Julio de 1952 (Law of July 24, 1952), the first commonwealth governor, Luis Muñoz Marín, used a dark blue shade matching the flag of the United States as the de facto color of the equilateral triangle of the flag. The dark blue shade of the flag used by Muñoz Marín government also matches the shade of blue featured on the original, authenticated Lares flag exhibited in Spain. |

| Flag of the United States | 1959-1960 | National flag of the United States flown in the island of present-day Puerto Rico as an unincorporated and organized American territory with autonomous local, democratic government, officially named the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Spanish: Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit. 'Free Associated State of Puerto Rico') upon its establishment in 1952. The flag features 49 stars, representing the 49 states of the American union at the time. |