Ramstein air show disaster

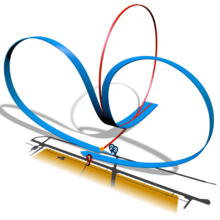

The three aircraft colliding | |

| Collision | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 28, 1988 |

| Summary | Mid-air collision |

| Site | USAF Ramstein Air Base Rhineland-Palatinate West Germany 49°26′18″N 007°36′13″E / 49.43833°N 7.60361°E |

| Total fatalities | 70 |

| Total injuries | 502 |

| First aircraft | |

| Type | Aermacchi MB-339PAN |

| Name | Callsign "Pony 10" |

| Operator | Frecce Tricolori Aeronautica Militare |

| Crew | Lt. Col. Ivo Nutarelli (killed) |

| Second aircraft | |

| Type | Aermacchi MB-339PAN |

| Name | Callsign "Pony 1" |

| Operator | Frecce Tricolori Aeronautica Militare |

| Crew | Lt. Col. Mario Naldini (killed) |

| Third aircraft | |

| Type | Aermacchi MB-339PAN |

| Name | Callsign "Pony 2" |

| Operator | Frecce Tricolori Aeronautica Militare |

| Crew | Cpt. Giorgio Alessio (killed) |

| Ground casualties | |

| Ground fatalities | 67 |

| Ground injuries | 500 |

The Ramstein air show disaster occurred on Sunday, 28 August 1988 during the Flugtag '88 airshow at USAF Ramstein Air Base near Kaiserslautern, West Germany. Three aircraft of the Italian Air Force display team collided during their display, crashing to the ground in front of a crowd of about 300,000 people. There were 70 fatalities (67 spectators and 3 pilots), and 346 spectators sustained serious injuries in the resulting explosion and fire. Hundreds more had minor injuries.[1] At the time, it was the deadliest air show accident in history until a 2002 crash at the Sknyliv air show in Ukraine that killed 77.[2]

Background

[edit]Ten Aermacchi MB-339 PAN jets from the Italian Air Force display team, Frecce Tricolori, were performing their "pierced heart" (Italian: Cardioide, German: Durchstoßenes Herz) formation. In this formation, two groups of aircraft trace out a heart shape in front of the audience along the runway. As they reach the lower tip of the heart, the two groups pass each other parallel to the runway. The heart is then pierced by a lone aircraft, flying in the direction of spectators.

The crash

[edit]

The mid-air collision took place as the two heart-forming groups passed each other and the heart-piercing aircraft hit them. One of the pilots finished the maneuver too early. The piercing aircraft crashed onto the runway and consequently both the fuselage and resulting fireball of aviation fuel tumbled into the spectator area, hitting the crowd and coming to rest against a refrigerated trailer being used to dispense ice cream to the various vendor booths in the area.

At the same time, one of the damaged aircraft from the heart-forming group crashed into the emergency medical evacuation UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter, injuring the helicopter's pilot, Captain Kim Strader. He died 20 days later, on Saturday, 17 September 1988, at Brooke Army Medical Center in Texas from burns he suffered in the accident.

The pilot of the aircraft that hit the helicopter ejected, but was killed as he hit the runway before his parachute opened. The third aircraft disintegrated in the collision and parts of it were strewn along the runway.

After the crash, the remaining aircraft regrouped and landed at Sembach Air Base.

Emergency response

[edit]Scope

[edit]Of the 31 people who died on impact, 28 had been hit by debris in the form of airplane parts, concertina wire, and items on the ground.[3] Sixteen of the fatalities occurred in the days and weeks after the disaster due to severe burns; the last was the burned and injured helicopter pilot.[4] About 500 people had to seek hospital treatment following the event,[citation needed] and over 600 people reported to the clinic that afternoon to donate blood.[citation needed]

Criticism

[edit]The disaster revealed serious shortcomings in the handling of large-scale medical emergencies by German civil and American military authorities. US military personnel did not immediately allow German ambulances onto the base, and the rescue work was generally hampered by a lack of efficiency and coordination.[5] The rescue coordination center in Kaiserslautern was unaware of the disaster's scale as much as an hour after it occurred, even though several German medevac helicopters and ambulances had already arrived on site and left with patients. American helicopters and ambulances provided the quickest and largest means of evacuating burn victims, but lacked sufficient capacities for treating them, or had difficulty finding them. Further confusion was added by the American military's usage of different standards for intravenous catheters from German paramedics. A single standard was codified in 1995, updated with a newer version in 2013 and an amendment to the current standard in 2017.[6]

Actions

[edit]A crisis counseling center was immediately established at the nearby Southside Base Chapel and remained open throughout the week. Base mental health professionals provided group and individual counseling in the following weeks, and they surveyed the response workers two months following the tragedy and again six months after the disaster to gauge recovery.[7]

Timeline

[edit]| Time | Details[8] |

|---|---|

| 15:40 | Take-off of the Frecce Tricolori |

| 15:44 | Collision |

| 15:46 | Fire fighters arrive |

| 15:48 | First American ambulance arrives |

| 15:51 | First American ambulance helicopter arrives |

| 15:52 | Second American ambulance helicopter arrives |

| 15:54 | First American ambulance helicopter takes off |

| 16:10 | German ambulance helicopter Christoph 5 from Ludwigshafen arrives |

| 16:11 | German ambulance helicopter Christoph 16 from Saarbrücken arrives |

| 16:13 | 10 American and German ambulances arrive |

| 16:28 | About 10–15 ambulances arrive. Eight medical helicopters (US Air Force, ADAC, SAR) at the scene |

| 16:33 | First medical helicopter of the Rettungsflugwacht arrives |

| 16:35 | Doctor on emergency call over the radio: "We are searching for burnt patients that are pulled and transported unaided away from us by the Americans. They told us nobody from them are here no more. Not all the injured people are transported away by helicopter or ambulance. There is total chaos around us and some of the injured are even transported on pickup trucks that are not leaving on emergency exit, they are driving beside the drifting visitors. It was a terrible sight to see people with burnt clothes and sagging burnt skin, squirming with pain of transfixed and shocked with pain[clarification needed] on these vehicles." |

| 16:40 | First low platform trailer for transport of the dead bodies arrives |

| 16:45 | Second low platform trailer for transport of the dead bodies arrives |

| 16:47 | At that time the German headquarters for emergencies had no clue of the dimensions, obvious by the radio communication: "Yes, and that is the problem. We don't know yet what had happened, how many injuries and what else. The leading emergency medical did not send any feedback yet. He wants to have a synoptic view first" |

| 17:00 | At that time several medics arrive with helicopters. Later they said: "At the time we arrived shortly after 5:00 there were no injured people no more. We could see that the last badly injured people were loaded into American helicopters. We could see some pickup trucks with injured people transporting them away. It was not possible to find an officer in charge, a director of operations or even a contact person [...] so we got to the Johannis hospital in Landstuhl by own initiative. Asking several action forces, paramedics, police officers nobody could name a director of operations. I was asking for a managing paramedic of the operation to coordinate the evacuation. But there was none." |

| 18:05 | An ambulance helicopter arrives at the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center. The paramedic said later: "We found a large number of severely burnt, badly injured people absolutely unaided. [...] When I arrived in Landstuhl, severely burnt people partly lay on wooden planks and no paramedics were there. After I aided an injured person and left her with a hospital nurse that attended us at the flight, I was treating several injured people at the helicopter landing zone at the military hospital and did not see even one American medic there" |

| 18:20 | Dead bodies are transported away from the scene with the two platform trucks |

| 18:30 | A bus full of injured people arrives in Ludwigshafen (80 km; 50 miles away). A paramedic later said: "5 severely burnt people were inside the bus. There was no paramedic attending this transport. Just a non-German speaking driver unfamiliar with the area, on an odyssey through the town until he was able to find the hospital." |

Investigation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

Several different video recordings of the accident were made. They show that the "piercing" aircraft (Pony 10) came in too low and too fast at the crossing point with the other two groups (five aircraft on the left and four on the right) as they completed the heart-shaped figure. Lead pilot Lieutenant Colonel Ivo Nutarelli, flying Pony 10, was unable to correct his altitude or lower his speed, and collided with the leading airplane (Pony 1, piloted by Lt. Col. Mario Naldini) of the left formation "inside" the figure, destroying the plane's tail section with the front of his aircraft.[citation needed] Pony 1 then spiralled out of control, hitting the plane on its lower left (Pony 2, piloted by Captain Giorgio Alessio). Lt. Col. Naldini ejected but was killed as he hit the runway before his parachute opened. His plane crashed onto a taxiway near the runway, destroying a medevac helicopter and fatally injuring its pilot, Captain Kim Strader. Pony 2, the third plane involved in the disaster, was severely damaged from the impact with Pony 1, and crashed beside the runway, exploding in a fireball. Its pilot, Captain Alessio, died on impact.

Pony 10, the aircraft that started the crash, continued on a ballistic trajectory across the runway, completely out of control and in flames, its forward section destroyed by the impact with Pony 1. The plane hit the ground ahead of the spectator stands, exploding in a fireball and destroying a police vehicle parked inside the concertina-wire fence that defined the active runway area. The plane continued, cartwheeling for a distance before picking up the three-strand concertina-wire fence, crossing an emergency access road, slamming into the crowd, and hitting a parked ice cream van. The area of the crash, being centered on the flightline and as close to the airshow as civilian spectators could get, had been considered the "best seats in the house", and was densely packed. The entire incident, from the collision of the first two planes to the crash into the crowd, took less than seven seconds, leaving almost no time for spectators to escape. The low altitude of the maneuver (45 meters above the crowd) also contributed to the short time frame.

An examination of photos and footage from the disaster showed that Pony 10's landing gear came down at some point; it has been suggested that this could have been lowered intentionally as a last second effort by Lt. Col. Nutarelli to slow his plane down and avoid the impact, but there is no substantial evidence pointing to this; the undercarriage could have been lowered by a number of factors. In April 1991, Werner Reith, a German journalist from the newspaper Die Tageszeitung, suggested in an article that the Ramstein disaster could have been caused by some sudden technical problem—or even sabotage—in Nutarelli's plane. No supporting evidence could be collected. Reith pointed out that Lt. Col. Nutarelli and Lt. Col. Naldini were supposed to know details about another air disaster, the 1980 Ustica massacre, citing Italian press sources.[9] Judge Rosario Priore, who was investigating the case at the time, found that they were performing training flights nearby minutes before the Ustica incident, but he definitely rejected their deaths as sabotage.

References in popular culture

[edit]

- In games

- A similar disaster is portrayed in the German made strategy PC game Emergency: Fighters for Life as Mission 22

- In literature

- Both Ramstein Air Force Base and the Ramstein air disaster figure as plot points in Donna Leon's second Guido Brunetti novel, Death in a Strange Country (1993)

- In music

- The Neue Deutsche Härte band Rammstein was named after this catastrophe. The second "m" was initially added by mistake, but the band eventually embraced the misspelling as its literal translation is "ramming-stone."[10] Rammstein's self-titled song (on the album Herzeleid (1995)) is also a reference to the event.[11]

- DJ and record producer Boris Brejcha was a 6-year old in the crowd, and was badly burned by the flames. He describes his style as high-tech minimal, as it reflects his subsequent isolation, using the Venetian Carnival mask as his logo.

- In television

- The disaster was featured on the 22 February 2008, episode of Shockwave, on The History Channel and the December 10, 2000 episode of World's Most Amazing Videos as well as an episode of Real TV.

- A German TV film Ramstein: Das durchstoßene Herz ('Ramstein: The Pierced Heart') was premiered at the Munich International Film Festival in June 2022 and broadcast on Das Erste in October.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 1988 Ramstein air crash stirs memories Archived 2011-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, www.stripes.com

- ^ "4 held over worst air show crash". Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Ramstein survivor support group. "Ramstein-Katastrophe".

- ^ "SL Army officer burned in air show crash dies". Deseret News. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Ramstein Air Show Disaster Kills 70, Injures Hundreds". Wired. August 2009.

- ^ ISO 10555-1:2013/ Amd 1:2017 Intravasuclar cathethers - Sterile and single-use cathethers - Part 1: General requirements - Amendment 1. - accessed 26 August 2023

- ^ Ursano, Robert J.; Fullerton, Carol S.; Wright, Kathy M.; McCarroll, James E (eds.). Trauma, Disasters and Recovery. Department of Military Psychiatry. p. 12ff – via Defense Technical Information Center.

- ^ Katastrophen-Nachsorge – Am Beispiel der Aufarbeitung der Flugkatastrophe von Ramstein 1988, Hartmut Jatzko, Sybille Jatzko, Heiner Seidlitz, Verlag Stumpf & Kossendey 2. Auflage. 2001, ISBN 3-932750-54-3.

- ^ Reith, Werner (20 April 1991). "Tod in Ramstein: Spur in Italien". Die Tageszeitung. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Galenza/Havemeister (2003). Feeling B. Mix mir einen Drink. Berlin: Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf. p. 262.

- ^ "FAQ". Herzeleid. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2019. Quote from MTV interview.

- ^ "Ramstein: Das durchstoßene Herz - TV Movie (2022)". imdb.com. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

External links

[edit]- Le crash de Ramstein (in French) – extensive photo gallery

- Robert-Stetter.de – Photo gallery of the incident

- West Germany Hellfire from The Heavens – Time magazine article from 12 September 1988

- Airliners.net – Marc Heesters' photograph of the incident

- Ramstein – The air show catastrophe and its aftermath, Same description in German – Information about 2008 documentary, a WDR and SWR co-production

- Complete aerobatic maneuver including crash analysis (video)

- Documentazione tecnico-formale relativa all'incidente (in Italian) - Official report of the Italian Air Force

- Ramstein 1988: Death falling from the clear blue sky Comprehensive report by Austrian Aviation Magazine 'AustrianWings' on 30th anniversary of the tragedy (archived)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch