Roméo Dallaire

Roméo Dallaire | |

|---|---|

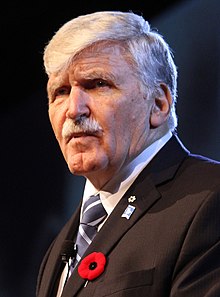

Roméo Dallaire in 2017 | |

| Canadian Senator from Quebec (Gulf) | |

| In office March 25, 2005 – June 17, 2014 | |

| Nominated by | Paul Martin |

| Appointed by | Adrienne Clarkson |

| Preceded by | Roch Bolduc |

| Succeeded by | Éric Forest |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Roméo Antonius Dallaire June 25, 1946 Denekamp, Netherlands |

| Political party | Independent (2014–Present) |

| Other political affiliations | Liberal (2005–2014) |

| Spouse | Marie-Claude Michaud (m. 2020)Elizabeth Roberge (m. 1976; div. 2019) |

| Children | 3 (Willem, Catherine, Guy) |

| Alma mater | Royal Military College of Canada (BSc) |

| Website | www |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Canada |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1963–2000 |

| Rank | Lieutenant-general |

| Commands | |

| Awards | Officer of the Order of Canada Companion of the Order of Military Merit Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec Meritorious Service Cross Canadian Forces' Decoration |

Roméo Antonius Dallaire OC CMM GOQ MSC CD (born June 25, 1946) is a retired Canadian politician and military officer who was a senator from Quebec from 2005 to 2014, and a lieutenant-general in the Canadian Armed Forces. He notably was the force commander of UNAMIR, the ill-fated United Nations peacekeeping force for Rwanda between 1993 and 1994, and for trying to stop the genocide that was being waged by Hutu extremists against Tutsis. Dallaire is a Senior Fellow at the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS) and co-director of the MIGS Will to Intervene Project.[4][5]

Early life and education

[edit]Roméo Antonius Dallaire was born in Denekamp, Netherlands to Staff-Sergeant Roméo Louis Dallaire, a Canadian non-commissioned officer, and Catherine Vermeassen, a Dutch nurse. Dallaire came to Canada with his mother as a six-month-old baby on the Empire Brent, landing in Halifax on December 13, 1946. He spent his childhood in Montreal.

He enrolled in the Canadian Army in 1963, as a cadet at the Royal Military College Saint-Jean. In 1970 he graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada with a Bachelor of Science degree and was commissioned into The Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery.

In 1971, Dallaire applied for a Canadian passport to travel overseas with his troops and was surprised to discover that his birth in the Netherlands as the son of a Canadian soldier did not automatically make him a Canadian citizen.[6] He has subsequently become a Canadian citizen.

Dallaire has also attended the Canadian Land Force Command and Staff College, the United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College in Quantico, VA, and the British Higher Command and Staff Course.

He commanded the 5e Régiment d'artillerie légère du Canada. On July 3, 1989, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general. He then commanded the 5th Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group. He was also the commandant of Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean from 1990 to 1993.

Rwanda

[edit]Original mission

[edit]In late 1993, Dallaire received his commission as the Force Commander of UNAMIR, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda. Rwanda was in the middle of a civil war between the extremist Hutu government and a small Tutsi rebel faction. UNAMIR's goal was to assist in the implementation of the Arusha Accords. The Hutus worked through the Rwandan army and then-president of Rwanda, Juvénal Habyarimana, and the Tutsis through the rebel commander Paul Kagame, who is the president of Rwanda today. When Dallaire arrived in Rwanda, his mandate was to supervise the implementation of the Accords during a transitional period in which Tutsis were supposed to be given positions of power within the Hutu government.

There were early signs that something was amiss when, on January 22, 1994, a French DC-8 aircraft landed in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, loaded with ammunition and weapons for the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR). FAR was the Hutu army under Habyarimana's control. Dallaire was unable to seize the weapons, as this would have violated his UN mandate.

The Chief of Staff of the Rwandan Army told Dallaire that since the munitions were ordered before Arusha, the UN was not allowed to detain the shipment, and displayed paperwork showing that the weapons had been sent by Belgium, Israel, France, Britain, the Netherlands, and Egypt. In addition to the arms deliveries, troops from the Rwandan government began checking identity cards which identified individuals as Hutus or Tutsis. These cards would later allow Hutu militias to identify their victims with accuracy.

Deteriorating conditions

[edit]On the night of 6 April 1994, an airplane carrying Habyarimana was shot down over Kigali Airport. The President of Burundi was also on board. Coincidentally, wreckage from the crash landed in Habyarimana's own backyard. Following the airplane crash, Hutu extremists, with help from the Rwandan government and the Rwandan Armed Forces, blamed the assassination on the Tutsis and used this as a pretext for systematic execution of the Tutsis faction, as well as many of the moderate elected officials of the new government. Dallaire immediately ordered ten Belgian soldiers to protect the new prime minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, but Madame Agathe and her husband were killed, and later the next day, the Belgian soldiers were found dead.

The ten Belgian UN Paracommandos had been intercepted by the Rwandan government forces (FAR), taken to a military camp as hostages, and murdered there. Passing the entrance of the camp on his way to a meeting of the FAR commanders, Gen. Dallaire caught a glimpse of some bodies on the ground. In a 2007 trial in Belgium, the Rwandan camp commander charged with the peacekeepers' murder testified that he had warned Gen. Dallaire that they were going to be killed, and that Dallaire had promised to send help. Storming Camp Kigali was beyond the means of his meagre force, however, and instead, he forbade the other Belgian troops to take action.[7]

Colonel Luc Marchal, commander of UNAMIR forces in the Kigali sector, has defended this decision on the grounds that to attack would have put the ill-equipped UNAMIR forces in an adversarial role against the Rwandan military, escalated the situation, and endangered their lives and those of the 331 unarmed UN observers.[8] In the 2007 trial of the Rwandan officer Bernard Ntuyahaga on charges of allowing the massacre to take place, Belgian Investigating judge Damien Vandermeersch cited among other "obstacles to his work, the refusal of the United Nations to allow him to hear from General Romeo Dallaire."[9] But Dallaire had testified extensively before the ICTR in 2004 about the peacekeepers and other matters, all of which was a matter of public record available to Judge Vandermeersch, and in which a decision was pending. Colonel Théoneste Bagosora was later convicted by ICTR in December 2008 of being responsible for the peacekeepers' murders.[10]

Seeing the situation in Rwanda deteriorating rapidly, Dallaire pleaded for logistical support and reinforcements of 2,000 soldiers for UNAMIR; he estimated that a total of 5,000 well-equipped troops would give the UN enough leverage to put an end to the killings. The UN Security Council refused, partly due to US opposition. US policy on interventions had become skeptical following the death of several U.S. soldiers in Mogadishu, Somalia the year before; this new policy was outlined in Presidential Decision Directive 25 by President Clinton. The Security Council voted to reduce UNAMIR further to 270 troops [1].

Since the UN mandate had not changed, the Belgian troops started evacuating, and the Europeans withdrew. As the Belgians departed on 19 April, Dallaire felt an acute sense of betrayal; 'I stood there as the last Hercules left...and I thought that almost exactly fifty years to the day my father and my father-in-law had been fighting in Belgium to free the country from fascism, and there I was, abandoned by Belgian soldiers. So profoundly did I despise them for it...I found it inexcusable.'[11]

Genocide

[edit]Following the withdrawal of Belgian forces, whom Dallaire considered his best-trained[12] and best-equipped, Dallaire consolidated his contingent of Pakistani, Canadian, Ghanaian, Tunisian, and Bangladeshi soldiers in urban areas and focused on providing areas of "safe control" in and around Kigali. Most of Dallaire's efforts were to defend specific areas where he knew Tutsis to be hiding. Dallaire's staff—including the U.N.'s unarmed observers—often relied on its U.N. credentials to save Tutsis, heading off Interahamwe attacks even while being outnumbered and outgunned. Dallaire and his staff are credited with saving the lives of 32,000 people.[13]

Dallaire gave the major force contributors different evaluations for their work. In his book, he gave the Tunisian and Ghanaian contingents high praise for their valiant and competent work. Ghana lost three peacekeepers. On the other hand, he criticized the Bangladeshi contingent for being poorly trained and poorly equipped. He was especially critical of the Bangladeshi contingent's leadership because of their incompetence and lack of loyalty to the mission and UN chain of command.

End to the Genocide

[edit]As the massacre progressed and press accounts of the genocide grew, the U.N. Security Council backtracked on its position and voted to establish UNAMIR II, with a strength of 5,500 men in response to the French plan to occupy portions of the country. The so-called Operation Turquoise, the presence of French troops, was initially opposed by Dallaire because the French had a history of backing the Hutus and the Rwandan Armed Forces, and thus their presence would be opposed by Kagame and the rebel RPF. It was not until early July, when RPF troops under Kagame swept into Kigali, that the genocide ended. By August, the French had handed their portion of the country to the RPF, giving Kagame effective control of all of Rwanda.

As revealed through testimony at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the genocide was brutally efficient, lasting for a total of 100 days and leading to the murder of between 800,000 and 1,171,000 Tutsi, Hutu moderates and Twa. Over two million people were displaced internally or in neighbouring countries. The Genocide ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Front gained control of Rwanda on July 18, 1994, though recrimination, retribution, and criminal prosecutions continue to the present day.

Controversy

[edit]Dallaire has been criticized by retired Canadian General Lewis MacKenzie for protecting UN soldiers when 10 Belgian paratroopers were killed on duty.[14]

It has been alleged by the families that Dallaire failed to intervene while passing just 20 yards from the paratroopers.[15] Belgian authorities have stated that they would seek a penal indictment over his role in the deaths of the Belgian paratroopers.[16]

Dallaire was later criticized by the Belgian parliamentary commission for not preventing the murder of ten members of the 2nd Commando Battalion. In his answer to the martial council he would later say, "I did not know whether they were dead or injured."[17] He went on to meet officers of the Rwanda army at the Military School, but did not mention the event. The company of the Bangladeshi Battalion which had the task of Quick Reaction Force was ill-prepared and did not leave their barracks. After those events Belgium withdrew its forces from Rwanda. Dallaire considered them to be his best-trained[18] and best-equipped forces.

The commission of inquiry of the Belgian Senate in 1998 severely condemned Dallaire's actions during those days, stating it was "imprudent and unprofessional to have the Belgian escorts provided on 7 April with so few military precautions". In addition, the commission stated it "did not understand why general Dallaire, who had noted the blue beret bodies in the Kigali camp, did not communicate this immediately to the FAR's high-ranking officers at the meeting of the École supérieure and did not demand the urgent intervention of those Rwandan officers present. This appears to reflect considerable indifference on his part. Moreover, general Dallaire also neglected to inform his sector commander about what he had seen and to give the necessary instructions".[19][17]

The Belgian Minister of Foreign Affairs, during an interview, states that "...Dallaire was insulting in his comments and whose cowardice was demonstrated by a lack of responsibility when the situation required leadership on his part".[20]

In his book, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda, General Dallaire details his decision to send 10 soldiers to protect the Prime Minister during the "apocalyptic" first hours of the genocide.[21]

Life after Rwanda

[edit]

Upon his return to Canada from UNOMUR and UNAMIR, Dallaire was appointed to two simultaneous commands in September 1994: Deputy Commander of Land Force Command (LFC) in Saint-Hubert, Quebec and Commander of 1 Canadian Division. In October 1995, Dallaire assumed command of Land Force Quebec Area.

In 1996, Dallaire was promoted to Chief of Staff and to the Assistant Deputy Minister (Personnel) Group at NDHQ. In 1998 he was assigned to Assistant Deputy Minister (Human Resources – Military) and in 1999 was appointed Special Advisor to the Chief of the Defence Staff on Officer Professional Development.

Dallaire suffers from posttraumatic stress disorder and, in 2000, attempted suicide by combining alcohol with his anti-depressant medication, a near fatal combination which left him comatose.[22] Dallaire is an outspoken supporter of raising awareness for veterans' mental health.

In January 2004, Dallaire appeared at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda to testify against Colonel Théoneste Bagosora. The testimony was critical to the outcome of the trial, and in December 2008 Bagosora was convicted of genocide and for the command responsibility of the murders of the 10 Belgian Peacekeepers. The trial chamber held that: "it is clear that the killing of the peacekeepers formed part of the widespread and systematic attack",[10] while at the same time holding that: "the evidence suggests that these killings were not necessarily part of a highly coordinated plan."[23]

He later worked as a Special Advisor to the Canadian Government on War Affected Children and the Prohibition of Small Arms Distribution, as well as with international agencies with the same focus, including child labour. He is a great proponent of the concept of institutionalism, and, in 2004–2005, he was a fellow at the Carr Center For Human Rights Policy at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government. He endorses the Genocide Intervention Network.

Dallaire was appointed to the Canadian Senate by Prime Minister Paul Martin on March 24, 2005. He sits as a Liberal, representing the province of Quebec. Dallaire noted that his family has supported both the Liberal Party of Canada and the Quebec Liberal Party since 1958. He was a strong supporter of Michael Ignatieff's unsuccessful 2006 bid for the leadership of the federal Liberal Party.

In 2007, Dallaire called for the reopening of Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean, saying "The possibility of starting a new program at the college—a military Cegep that would allow all officer cadets to spend two years in Saint-Jean before going to Kingston, instead of studying only in Kingston—is being considered. In the spirit of progress, would it be possible to support a principle as basic as the freedom of francophones in the Canadian Armed Forces by establishing a Cegep-style francophone bilingual military college."[24]

Concordia University announced on September 8, 2006, that Dallaire would sit as Senior Fellow at the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS), a research centre based at the university's Faculty of Arts & Science.[25] Later that month, on September 29, 2006, he issued a statement urging the international community to be prepared to defend Bahá'ís in Iran from possible atrocities.[26]

Dallaire has worked to bring an understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder to the general public. He was a visiting lecturer at several Canadian and American universities. He was a Fellow of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He pursued research on conflict resolution and the use of child soldiers. He has written several articles and chapters in publications on conflict resolution, humanitarian assistance and human rights.

In the media

[edit]In Samantha Power's 2002 landmark work on genocide in the 20th century, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide, Sen. Dallaire features largely in the recounting of the Rwanda Genocide. Power also wrote the foreword to Dallaire's book, Shake Hands with the Devil. In a 2004 opinion article published by the New York Times, Dallaire called upon NATO to intervene militarily alongside African Union troops to abort the genocide in Darfur. He concluded that, "having called what is happening in Darfur genocide and having vowed to stop it, it is time for the West to keep its word as well."[27]

Documentary and film

[edit]

In October 2002, the documentary The Last Just Man was released, which chronicles the Rwandan genocide and features interviews with Dallaire, Brent Beardsley, and others involved in the events that happened in Rwanda. It was directed by Steven Silver.

A documentary film, entitled Shake Hands with the Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire, which was inspired by the book and shows Gen Dallaire's return to Rwanda after ten years, was produced by the CBC, SRC and White Pine Pictures, and released in 2004. The film was nominated for two Sundance Film Festival Awards, winning the 2004 Sundance Film Festival Audience Award for World Cinema - Documentary and a nomination for Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema - Documentary. The film aired on CBC on January 31, 2005.

In 2004, PBS Frontline featured a documentary named The Ghosts of Rwanda.[28] In an interview[28] conducted for the documentary and recorded over the course of four days in October 2003, Dallaire said: "Rwanda will never ever leave me. It's in the pores of my body. My soul is in those hills, my spirit is with the spirits of all those people who were slaughtered and killed that I know of, and many that I didn't know...."

The 2004 film Hotel Rwanda featured a Canadian Forces colonel assigned to UN peacekeeping based on Dallaire, played by Nick Nolte. Dallaire is quoted as saying that neither the producer, nor Nolte himself, consulted with him before shooting the film. He said further that he did not agree with Nolte's portrayal, but did think that the film was "okay."[29]

A Canadian dramatic feature film Shake Hands with the Devil, adapted from Dallaire's 2003 book and starring Roy Dupuis as Lieutenant-General Dallaire, started production in mid-June 2006, and was released on 28 September 2007. Dallaire participated in a press conference about the film held on June 2, 2006, in Montreal, a film for which he was consulted, as opposed to Hotel Rwanda. The film earned 12 Genie Award nominations and won one in the category Best Achievement in Music - Original Song for the song "Kaya" by Valanga Khoza and David Hirschfelder.[30] In September 2007, Shake Hands With The Devil won the Emmy award for Outstanding Documentary with The Documentary Channel, who presented it on their channel.

Song

[edit]Dallaire is the inspiration for the song Kigali by Canadian singer-songwriter Jon Brooks. The song appears on his album Ours And The Shepherds, which is about Canadian war stories and the problems faced by returning soldiers. His first verse is taken directly from Dallaire's book.

Also, Roméo Dallaire is the title of a folk song written by Canadian folk songwriter Andy McGaw. McGaw's song points squarely at the indifference and failure of the United Nations surrounding the Rwanda genocide.

Chorus of McGaw's song:

- Thank you for callin' the United Nations

- We can't take your call right now cause we're all on vacation

- If you need support hug your teddy bear

- If you're in big trouble boys better say your prayers

Dallaire is the subject of the song Run Roméo Run on the 2006 album The Great Western by Welshman James Dean Bradfield.

Awards and recognition

[edit]In 1996, Dallaire was made an Officer of the Legion of Merit of the United States, the highest military decoration available for award to foreigners, for his service in Rwanda. Dallaire was also awarded the inaugural Aegis Trust Award in 2002, and on October 10 of the same year, he was inducted as an Officer in the Order of Canada.

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's The Greatest Canadian program saw Dallaire voted, in 16th place, as the highest rated military figure. Several months after the broadcast, on March 9, 2005, Governor-General Adrienne Clarkson awarded Dallaire with the 25th Pearson Peace Medal. On October 11, 2006, the Center for Unconventional Security Affairs at the University of California, Irvine awarded Dallaire with the 2006 Human Security Award.

Dallaire has received honorary doctorates from a large number of Canadian and American universities. He received Doctor of Laws degrees from University of Saskatchewan, St. Thomas University, Boston College, the University of Calgary, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Athabasca University, Trent University, the University of Victoria, the University of Western Ontario, and Simon Fraser University, and an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree from the University of Lethbridge.

In June 2006, Dallaire was awarded a Doctorate of Humane Letters by the Queens College of the City University of New York (CUNY) in recognition of his efforts in Rwanda and afterwards to speak out against genocide. He received an ovation from the crowd for his comment that "no human is more human than any other". Dallaire was named a Fellow of the Ryerson Polytechnic University, and an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

His book Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda was awarded the Governor General's Literary Award for Non-Fiction in 2004.

General Dallaire planted a tree at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, Accra, Ghana in 2007 at the invitation of the Commandant, Major-General John Attipoe.

Dallaire was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2002, Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec in 2005. He was granted the Aegis Award for Genocide Prevention from the Aegis Trust (United Kingdom).

Dallaire was a recipient of the Vimy Award.[31]

As part of the 50th Anniversary commemoration of the founding of the Pugwash Peace Exchange, in 2007 General Dallaire accepted Sir Joseph Rotblat's Nobel Peace Prize.

There are elementary schools named after Dallaire in Vaughan, Ontario,[32] Winnipeg, Manitoba[33] and Ajax, Ontario.[34]

Also, a street is named after him in the Lincoln Park neighbourhood of Calgary, Alberta.[35]

Dallaire was one of the eight Olympic Flag bearers at the opening ceremony for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver.

Bibliography and filmography

[edit]- The Last Just Man (Canada, 2001, directed by Steven Silver)

- Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda

- Shake Hands With the Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire

- Shake Hands with the Devil (2007 film)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Roméo Dallaire a trouvé son havre de paix". La Terre de Chez Nous (in French). September 20, 2019. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Gingras, Pierre (August 29, 2020). "VŒUX DE BONHEUR". Le Journal de Québec. Archived from the original on August 30, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Une histoire de cœur mêle le général Dallaire à une poursuite de 365 000$". TVA Nouvelles. April 5, 2019. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ "Fellows - Concordia University". www.concordia.ca. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Will to Intervene (W2I) - Concordia University". www.concordia.ca. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Passports and Citizenship Problems facing Canadian War Brides of World War Two, births, weddings, marriages to Canadian servicemen". Archived from the original on October 29, 2006. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- ^ R. Dallaire, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda, (Knopf Canada, 2003)

- ^ L. Melvern, A People Betrayed: The role of the West in Rwanda's genocide (Zed Books: London, 2000)

- ^ "25.04.07 - RWANDA/BELGIUM - NTUYAHAGA - JUDGING THE IMPOSSIBLE SAYS A JUDGE TO JURORS - Hirondelle News Agency - Fondation Hirondelle - Arusha". Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Paragraphs 2174-2177, Chapter IV: Legal Findings, page 551, Judgement and Sentence, 18 December 18, 2008, The Prosecutor v. Bagosora et al., Case No. ICTR-98-41-T

- ^ Martin Meredith, The State Of Africa, Chapter 27 (The Free Press, London, 2005)

- ^ 2005, Pilger, John (ed), page 451, 'Tell Me No Lies', Vintage Press, London. ISBN 978-0-099-43745-1

- ^ Chrom, Sol (May 28, 2014). "Roméo Dallaire: from the Netherlands to Rwanda to Canada's Senate". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved December 22, 2024.

- ^ Gessell, Paul (October 17, 2008). "MacKenzie vs. Dallaire". Ottawa Citizen. Ottawa, Ontario. p. A3. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rwanda Belgians Families". Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ "Great Lakes Documentation Network (Geneva)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Parliamentary commission of inquiry regarding the events in Rwanda, Complete report in the name of commission of inquiry by Mr. Mahoux and Mr. Verhofstadt Archived April 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch)

- ^ Pilger, John (ed) (2005), page 451, 'Tell Me No Lies', Vintage Press, London. ISBN 978-0-09-943745-1

- ^ Parliamentary commission of inquiry regarding the events in Rwanda, Report in the name of commission of inquiry by Mr. Mahoux and Mr. Verhofstadt, chapter 4 Archived April 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ "RWANDA • Le génocide des Tutsi". Archived from the original on February 11, 2005.

- ^ "Shake Hands with the Devil by Romeo Dallaire". Penguin Random House Canada.

- ^ "CBC News Indepth: Romeo Dallaire". CBC News. March 9, 2005. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ^ Paragraphs 791 & 795, Pages 198-199, Judgement and Sentence, 18 December 18, 2008, The Prosecutor v. Bagosora et al., Case No. ICTR-98-41-T

- ^ "Debates of the Senate, 1st Session, 39th Parliament" (PDF). May 3, 2007. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ "Senator Roméo Dallaire Partners With Concordia". Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies. September 8, 2008. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ^ "Romeo Dallaire, expert on genocide, expresses concern for Baha'i community in Iran". September 29, 2006. Archived from the original on May 26, 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2006.

- ^ Dallaire, Roméo (October 4, 2004). "Looking at Darfur, Seeing Rwanda". Reprinted from The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ^ a b "Ghosts of Rwanda". PBS. April 2004. Archived from the original on January 16, 2005. Retrieved January 17, 2005.

- ^ Romeo Dallaire, Still Bedeviled Archived November 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, February 9, 2005

- ^ "Shake Hands with the Devil (2007) - Awards". IMDb. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ "e-Veritas » Blog Archive » Misc". Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "Pages - School Information". www.yrdsb.ca. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ "Ecole Romeo-Dallaire- Winnipeg (Ecole francaise)". Archived from the original on May 26, 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ^ "Roméo Dallaire P.S." Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ "Google Maps". Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

Books

[edit]- 4237 Dr. Adrian Preston & Peter Dennis (Edited) "Swords and Covenants" Rowman And Littlefield, London. Croom Helm. 1976.

- H16511 Dr. Richard Arthur Preston "Canada's RMC - A History of Royal Military College" Second Edition 1982

- H1877 R. Guy C. Smith (editor) "As You Were! Ex-Cadets Remember". In 2 Volumes. Volume I: 1876–1918. Volume II: 1919–1984. RMC. Kingston, Ontario. The R.M.C. Club of Canada. 1984

External links

[edit]- Biography and picture, from Harvard's Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government.

- Biography of Senator Dallaire on the Canadian Parliament Official Site

- Liberal Senate Forum

- Canada Council of the Arts: brief biography, high-resolution image, and review of Dallaire's autographical book Shake Hands with the Devil

- CBC Biography of LGen Roméo Dallaire

- CBC Digital Archives – Witness To Evil: Roméo Dallaire and Rwanda

- CBC News article on appointment of Roméo Dallaire to the Canadian Senate

- Moving from Words to Actions Panel discussion hosted by Aegis Trust on January 25, 2006.

- Transcript of interview of LGen Dallaire in Ghosts of Rwanda documentary on PBS Frontline.

- Transcript of interview of LGen Dallaire at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, conducted in Washington D.C., June 12, 2002.

- Transcript of interview of General Dallaire on BBC's Hardtalk in 2002

- Romeo Dallaire Interview on The Hour

- Rwanda: Genocide Survivor Wants to Sue Belgium

- General Romeo Dallaire - United Nations/Canada

- Centre for Addiction & Mental Health interview with Romeo Dallaire about PTSD

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch