Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter

Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Director of Central Intelligence | |

| In office May 1, 1947 – October 7, 1950 | |

| President | Harry Truman |

| Deputy | Edwin K. Wright |

| Preceded by | Hoyt Vandenberg |

| Succeeded by | Walter B. Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Roscoe Henry Hillenkoetter May 8, 1897 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | June 18, 1982 (aged 85) New York City, U.S.] |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Spouse | Jane Clark |

| Education | United States Naval Academy (BS) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1915–1957 |

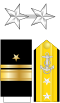

| Rank | Vice Admiral |

| Commands | Commanding Officer, USS Missouri Commander, 1st Cruiser Division Commander, 3rd Naval District |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II Korean War |

Roscoe Henry Hillenkoetter (May 8, 1897 – June 18, 1982) was the third director of the post–World War II United States Central Intelligence Group (CIG), the third Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and the first director of the Central Intelligence Agency created by the National Security Act of 1947. He served as DCI and director of the CIG and the CIA from May 1, 1947, to October 7, 1950, and, after his retirement from the United States Navy, was a member of the board of governors of National Investigations Committee On Aerial Phenomena (NICAP) from 1957 to 1962.

Education and military career

[edit]Born in St. Louis, Missouri on May 8, 1897, Hillenkoetter graduated from the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in 1919. He served with the Atlantic Fleet during World War I and joined the Office of Naval Intelligence in 1933. He served several tours in naval intelligence, including as assistant naval attaché to France, Spain, and Portugal. During the Spanish Civil War, he coordinated the evacuation of Americans from the country. After the German invasion of France, Hillenkoetter entered Vichy France and aided the underground movement. As executive officer of the USS West Virginia (BB-48), he was wounded during the attack on Pearl Harbor, and afterwards was officer in charge of intelligence on Chester W. Nimitz's Pacific Fleet staff until 1943. He briefly served as commander of the destroyer tender USS Dixie before joining the Bureau of Naval Personnel in 1944.

After the war, then-Captain Hillenkoetter commanded the USS Missouri in 1946 before returning to his pre-war posting as naval attaché in Paris before becoming head of the Central Intelligence Group (CIG) in May 1947.[1]

Director of Central Intelligence

[edit]President Truman persuaded a reluctant Hillenkoetter, then a rear admiral, to become Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and run the Central Intelligence Group (September 1947). Under the National Security Act of 1947 he was nominated and confirmed by the U.S. Senate as DCI, now in charge of the newly established Central Intelligence Agency (December 1947). At first, the U.S. State Department directed the new CIA's covert operations component, and George F. Kennan chose Frank Wisner to be its director. Hillenkoetter expressed doubt that the same agency could be effective at both covert action and intelligence analysis.[2]

As DCI, Hillenkoetter was periodically called to testify before Congress. One instance concerned the CIA's first major Soviet intelligence failure, the failure to predict the Soviet atomic bomb test (August 29, 1949). In the weeks following the test, but prior to the CIA's detection of it, Hillenkoetter released the September 20, 1949 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) stating, "the earliest possible date by which the USSR might be expected to produce an atomic bomb is mid-1950 and the most probable date is mid-1953."[3] Hillenkoetter was called before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (JCAE) to explain how the CIA not only failed to predict the test, but also how they did not even detect it after it occurred. JCAE members were steaming that the CIA could be taken by such surprise.[4] Hillenkoetter imprecisely replied that the CIA knew it would take the Soviets approximately five years to build the bomb, but the CIA misjudged when they started:

We knew that they were working on it, and we started here, and this organization [CIA] was set up after the war and we started in the middle and we didn't know when they had started and it had to be picked up from what we could get along there. That is what I say: this thing of getting a fact that you definitely have on the exploding of this bomb has helped us in going back and looking over what we had before, and it will help us in what we get in the future. But you picked up in the mid-air on the thing, and we didn't know when they started, sir.[5]

The JCAE was not satisfied with Hillenkoetter's answer, and his and the CIA's reputation suffered among government heads in Washington, even though the press did not write about the CIA's first Soviet intelligence failure.[6]

The U.S. government had no intelligence warning of North Korea's invasion (June 25, 1950) of South Korea. DCI Hillenkoetter convened an ad hoc group to prepare estimates of likely communist behavior on the Korean peninsula; it worked well enough that his successor institutionalized it.

Two days prior to North Korea's invasion of South Korea, Hillenkoetter went before Congress (the House Foreign Affairs Committee) and testified that the CIA had good sources in Korea, implying that the CIA would be able to provide warning before any invasion.[7] Following the invasion, the press suspected the administration was surprised by it,[8] and wondered whether Hillenkoetter would be removed.[9] The DCI was not influential with President Harry S. Truman, but Hillenkoetter insisted to the President that as the Director of Central Intelligence, it would be politically advantageous to testify before Congress to try to remedy the situation. After the testimony, some Senators told the Washington Post that Hillenkoetter confused them when explaining the CIA did not predict when North Korea would invade by saying it was not the CIA's job to analyze intelligence, just to pass it on to high-ranking policymakers.[10] Even though most senators believed Hillenkoetter ably explained the CIA's performance, many at the CIA were embarrassed by the news reports, and by mid-August the rumors of Hillenkoetter's removal were confirmed when President Truman announced that General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith would replace him as DCI.[11]

President Truman installed a new DCI in October. Nebraska Congressman Howard Buffett alleged that Hillenkoetter's classified testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee "established American responsibility for the Korean outbreak," and sought to have it declassified until his death in 1964.[12]

Resumption of active military duty

[edit]Admiral Hillenkoetter returned to the fleet, commanding Cruiser Division 1 of the Cruiser-Destroyer Force, Pacific Fleet from October 1950 to August 1951 during the Korean War. He then commanded the Third Naval District with headquarters in New York City from July 1952 to August 1956 and was promoted to the rank of vice admiral on 9 April 1956.[13]

His last assignment was as Inspector General of the Navy from 1 August 1956 until his retirement from the Navy on 1 May 1957.[14]

Board member of NICAP

[edit]The National Investigations Committee On Aerial Phenomena was formed in 1956, with the organization's corporate charter being approved October 24.[15] Hillenkoetter was on NICAP's board of governors from about 1957 until 1962.[16] Donald E. Keyhoe, NICAP director and Hillenkoetter's Naval Academy classmate, wrote that Hillenkoetter wanted public disclosure of UFO evidence.[17] Perhaps Hillenkoetter's best-known statement on the subject was in 1960 in a letter to Congress, as reported in The New York Times: "Behind the scenes, high-ranking Air Force officers are soberly concerned about UFOs. But through official secrecy and ridicule, many citizens are led to believe the unknown flying objects are nonsense."[18]

Death

[edit]Hillenkoetter lived in Weehawken, New Jersey, following his retirement from the Navy, until his death on June 18, 1982, at New York City's Mount Sinai Hospital.[19][20]

In fiction

[edit]Actor Leon Russom portrayed Hillenkoetter in an episode of Dark Skies, a 1996 television series presenting a story based conspiracies related to UFOs.

Awards

[edit]- Submarine Warfare insignia

- Distinguished Service Medal

- Legion of Merit

- Bronze Star Medal

- Victory Medal

- Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal

- American Defense Service Medal with "FLEET" clasp

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two battle stars

- World War II Victory Medal

- Navy Occupation Medal

- National Defense Service Medal

- Korean Service Medal with two campaign stars

- United Nations Korea Medal

- Officer of the Legion of Honor (France)

Dates of rank

[edit]| Ensign | Lieutenant junior grade | Lieutenant | Lieutenant commander |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 |

|  |  |  |

| 7 June 1919 | 7 June 1922 | 7 June 1925 | 30 June 1934 |

| Commander | Captain | Rear admiral | Vice admiral |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-5 | O-6 | O-7, O-8 | O-9 |

|  |  |  |

| 1 July 1939 | 18 June 1942 | 29 November 1946 | 9 April 1956 |

References

[edit]- ^ Richard H. Immerman (2006). The Central Intelligence Agency: Security Under Scrutiny. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 271–. ISBN 978-0-313-33282-1.

- ^ David Fromkin (January 1996). "Daring Amateurism: The CIA's Social History". Foreign Affairs (January/February 1996). Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. (1949). Intelligence Memorandum No. 225.; quoted in Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. p. 55.

- ^ Barrett, D.M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 56. [ISBN missing]

- ^ JCAE Hearing, 10-17-49, CIS Unpublished House Hearings; quoted in Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. pp. 59–60. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 62.

- ^ Congressional Record 7-13-50, p. 10086; quoted in Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 82.

- ^ (1950, June 25). The New York Times, p. 1.; quoted in Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. p. 83.

- ^ Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 83.

- ^ Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. pp. 84–85.

- ^ Barrett, D. M. (2005). The CIA and Congress: The Untold Story from Truman to Kennedy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. pp. 85, 89.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. Confessions of a Right-Wing Liberal, Ludwig von Mises Institute

- ^ "Third Naval District – Lists of Commanding Officers and Senior Officials of the US Navy". Washington, D.C.: Department of the Navy – Naval Historical Center. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

1952–1956 RADM Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter July 1952

1956–1958 RADM Milton E. Miles August 1956 - ^ "Roscoe Henry Hillenkoetter – Central Intelligence Agency". Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- ^ Dolan, Richard M. (2002). UFO's and the National Security State: Chronology of a Cover-up 1941–1973. Charlottesville, Virginia: Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 478. ISBN 1-57174-317-0.

- ^ "Photo Bios at NICAP site". Francis L. Ridge. Archived from the original on 2009-01-30. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

He resigned from NICAP in February 1962 and was replaced on the NICAP Board by a former covert CIA high official, Joseph Bryan III, the CIA's first Chief of Political & Psychological Warfare (Bryan never disclosed his CIA background to NICAP or Keyhoe).

- ^ Keyhoe, Donald E. (1973). Aliens from space; the real story of unidentified flying objects (1st ed.). Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-06751-8. (page 28 in the Dutch translation of that book)

- ^ United Press International (February 28, 1960). "Air Force Order on 'Saucers' Cited; Pamphlet by the Inspector General Called Objects a 'Serious Business'" (Fee). The New York Times. p. 30. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

Washington, February 27 (UPI) – The Air Force has sent its commands a warning to treat sightings of unidentified flying objects as "serious business" directly related to the nation's defense, it was learned today.

- ^ Roscoe H(enry) Hillenkoetter. Almanac of Famous People, 9th ed. Updated: 08/17/2007. Thomson Gale, 2007. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale Group, 2009 (http://www.galenet.com/servlet/BioRC) Fee (via Fairfax County Public Library). Document Number: K1601044553.

- ^ Kihss, Peter. "ADM. Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter, 85, First Director of the C.I.A., Dies", The New York Times, June 21, 1982. Accessed November 13, 2012. Vice Adm. Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter, the first director of the Central Intelligence Agency, died Friday night at Mount Sinai Hospital. He was 85 years old and had lived in Weehawken, N.J., since his retirement from the Navy in 1958."

External links

[edit]CIA Biographical Link

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch