Rudy Palace-Monastery

The Palace-Monastery of Rudy (Polish: Pocysterski Zespół Klasztorno-Pałacowy w Rudach (Wielkich) or German: Schloss Rauden or German: Kloster Rauden) is located in Rudy within the Racibórz County, Silesian Voivodeship, in southern Poland.[1]

The gothic Cistercian monastery was founded in the 13th century. During the 17th and 18th century, it was rebuilt in baroque style. It was a thriving school which included an impressive library. After the secularization, it became property of the prince of Hesse-Rothenburg and subsequently, the dukes of Ratibor and princes of Corvey, a branch of the Hohenlohe family. They made it their principal seat, which it remained up to the end of the Second World War. It was looted and set afire by the Red Army. The monastery church was immediately rebuilt, but the remaining buildings were only restored from the 1990s onwards. In 1998, it was transferred to the Diocese of Gliwice, and it has been an educational centre since, with the opportunity to stay the night over.

History

[edit]

Middle Ages

[edit]in 1258, Vladislaus I of Opole (1225-1281/2), Duke of Opole–Racibórz, founded a Cistercian monastery in Rudy.[2] The duke granted the abbey many privileges and granted them large estates and villages as well.[3] The first monks came from the Jędrzejów Abbey in southern Poland.[3] The first church was wooden.[3][4] But the construction of a brick church started soon afterwards.[3] It was completed around 1300 together with the eastern and western wings of the abbey.[3] The church was consecrated in 1303.[3]

The church of the monastery is dedicated to the Assumption of the blessed Virgin Mary.[4] It is considered the oldest Marian shrine in Silesia.[4] It attracted a lot of pilgrims, who wanted to see the image of the Virgin.[4]

Compared to other Cistercian monasteries, the income from the estate was not great although it had vineyards, and large forests and numerous streams around.[3] The most important economic activity was related to the brewery, wine cellar and the distillery.[3] Beer was brewed at least in the 14th and 15th centuries.[3] From the start, the monastery was an educational centre as well.[3]

Names of abbots of these times have survived, like Peter I (1258–1274), Martin I (1456–1471) and Peter III (1471–1492).

During the 15th and 16th century, the monastery was ravaged by war and looting due to the Hussite Wars, the Reformation and the Thirty Years War.[2][4] Several times, the monastery was plundered.[3] In 1625, there were only five monks left.[3]

17th and 18th centuries

[edit]

The 17th and 18th century were the heyday of the monastery. The start of the new and better times are associated with abbot Andreas Emanuel Pospel and his successors. Between 1671 and 1680, abbot Pospel had the monastery and the church rebuilt in baroque style.[2] A porch on the west side was erected in 1685.[3] After a fire in 1724, the western façade was completely redone, and between 1785 and 1790 the church interior was modernized.[3]

In the 18th century, the school was thriving and a boarding school was added in 1744.[2] The library of the monastery included 18,000 books and prints.[4]

In 1810, the monastery was secularized and went into ownership of the Prussian state.[4] The last abbot was Bernhard Galbiers.[4] The boarding school closed in 1816.[2] The library was divided among Silesian libraries and partly donated to waste paper.[4]

Dukes of Ratibor and Princes of Corvey

[edit]

After the secularization, the monastery and its estates were handed over to the Prussian minister Wilhelm Ludwig Sayn-Wittgenstein (1770–1851).[4] The monastery housed a military hospital for two years.[4] In 1812, the monastery went into the hands of the crown prince of Hesse-Kassel, William II.[2]

In 1820, Victor Amadeus, Landgrave of Hesse-Rotenburg (1779–1834) became the new owner of the Rudy monastery and its estates.[2][4][5] He started to transform the monastery into a princely residence. In both 1820 and 1822, he received in Rudy emperor Alexander I of Russia (1777–1825) as a guest.[4]

Although married twice, Victor Amadeus was childless and when he died in 1834, he bequeathed his possessions of the Silesian duchy of Ratibor (Czech: Ratiboř, Polish: Racibórz) and Prince of Corvey to his nephew, Victor, prince of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1818–1893).[4][5] These estates amounted to around 34,000 hectares in size and consisted mostly of forests. Besides the Rudy monastery, it also included the Corvey.

Victor was a member of the House of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst and eldest son of Franz Joseph, 1st Prince of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1787–1841), who was married to a younger sister of Victor Amadeus's wife.[5] In order to accept Victor Amadeus's inheritance, he waived his rights on the Schillingsfürst succession in favour his younger brother Chlodwig (1819–1901), who was to became Chancellor of Germany and Minister President of Prussia from 1894 to 1900.[5]

In 1840, Victor was created duke of Ratibor and prince of Corvey on 15 October 1840 by king Frederick William IV of Prussia (1795–1861).[5] Victor made Rudy his main seat and used the Corvey Abbey as his summer residence.[4] He further renovated the palace monastery and created a large landscape park around the residence.[4] The palace had around 120 rooms and halls.[4]

The last big renovation happened between 1900 and 1901 under Victor's son, duke Victor II (1847–1923), who was born at the palace.[2] Duke Victor II was married in 1877 to countess Maria Breunner-Enkevoirth (1856–1929), which brought the third great stately home in the Ratibor family, Schloss Grafenegg in Austria. The family belonged to the largest landowners in Germany.

The estate was often visited by royalty and higher nobility for the hunt: Field marshall Frederick von Wrangel and count Moltke in 1857; Frederick Francis II (1823–1883), grand duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, in 1860; the future emperor Frederick III (1831–1888) and his wife Victoria, Princess Royal (1840–1901) in 1866.[6] Emperor Wilhelm II visited Rudy various times for hunts, and was often the best hunter of his group, but 1910 was his latest visit.[6] Photojournalists captured him on picture and suggested in newspapers that pheasants were kept in baskets and were released as soon as the emperor took position.[6] This made his hunt much easier and the fact that he was the best hunter less impressive. Scandal broke out and despite an intensive investigation, the duke was not able to find out who leaked the story.[6] However, the emperor did not return to Rudy, and photojournalists were no longer invited to subsequent hunts.[6]

After the division of upper Silesia between Germany and Poland in 1922, Rudy remained on the German side of the border.[4] In the time of National Socialism or Nazism, the family was reluctant to the new political system.[4] However, it was not immune to the consequences.[4] Duke Victor III (1879–1945) lost his eldest son, Victor IV, during the Invasion of Poland in 1939, who participated as a soldier of the invading armoured units.[4]

At the end of the Second World War, the Ratibor-Corvey family had to flee Rudy for the advancing Russian troops. The Red Army looted the palace-monastery in Rudy and set it afire to hide their traces.[2][4] Both the church and the princely residence were destroyed.[4]

Duke Victor III passed in Corvey. His titles and the castles in Corvey and Grafenegg were inherited by his son Franz-Albrecht Metternich-Sándor (1920–2009), who was adopted by the last member of the princely Metternich family, princess Clementine von Metternich-Sandor (1870–1963). The son of Franz Albrecht, Victor V, is the current duke and lives in Corvey.

Communist times

[edit]

When Silesia came under Polish administration after World War II, the remains of the palace monastery and its estate were confiscated by the government. The church was completely reconstructed in 1947 and became the village church.[4] The remaining building remained in ruinous conditions as the authorities limited themselves to securing the site and nothing more.[4] Although, in the 1970s, part of the site was tidied up and cleared from the rubble.[4]

Modern times

[edit]In 1998, the palace monastery was transferred into the ownership of Diocese of Gliwice.[3][4] An intensive renovation of the monastery and the palace rooms started, of which the first stage was completed in 2008.[4] Also, the landscape park is being restored as well.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "Central Statistical Office (GUS) - TERYT (National Register of Territorial Land Apportionment Journal)" (in Polish). 2008-06-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i von Golitschek, Josef (1988). Schlesien – Land der Schlösser – Band 2 (in German). Mannheim: Orbis Verlag. pp. 111–114. ISBN 3-572-09275-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Rudy Raciborskie – Cistercian Abbey". medievalheritage.eu. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "Rudy Opactwo Historia". rudy-opactwo.pl (in Polish). 11 June 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Tiggesbäumker, Günter (1994). "Viktor 1. Herzog von Ratibor und Fürst von Corvey, Prinz zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1818-1893)" (PDF). Westfälische Zeitschrift (in German). 144: 265–288.

- ^ a b c d e "Wielki łowczy cesarz Wilhelm II i skandal w Raciborzu". ziemiaraciborska.pl (in Polish). 30 December 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

Literature

[edit]- Gessner, Adolf (1952). Abtei Rauden in Oberschlesien, Quellen und Darstellungen zur schlesischen Geschichte (in German). Kitzingen-Main: Holzner-Verlag/ Historischen Kommission für Schlesien.

- Sieber, Helmut (1971). Schlösser in Schlesien (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Wolfgang Weidlich. pp. 143–144.

- Grüger, Heinrich (1981). "Rauden, Zisterzienserabtei". Jahrbuch der schlesischen Friedrich-Wilhelm-Universität zu Breslau (in German). 22: 33–49.

- von Golitschek, Josef (1988). Schlesien – Land der Schlösser – Band 2 (in German). Mannheim: Orbis Verlag. pp. 111–114. ISBN 3-572-09275-2.

- Tiggesbäumker, Günter (1994). "Viktor 1. Herzog von Ratibor und Fürst von Corvey, Prinz zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1818-1893)" (PDF). Westfälische Zeitschrift (in German). 144: 265–288.

- Reddig, Wolfgang J. (1999). "Die Zisterzienserabtei Rauden". In Reddig, Wolfgang J. (ed.). Klöster und Landschaften, Zisterzienser westlich und östlich der Oder. Begleitband zur Ausstellung der Europa-Universität (in German). Frankfurt an der Oder: Viadrina. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-3931278199.

- Badstübner, Ernst; Tomaszewski, Andrzej; Winterfeld, Dethard; Brzezicki, Slawomir; Nielsen, Christine, eds. (2005). Schlesien (Dehio - Handbuch der Kunstdenkmäler in Polen) (in German). München: Deutscher Kunstverlag. pp. 814–816. ISBN 978-3422031098.

External links

[edit]- "Rudy Opactwo Pocysterski Zespół Klasztorno-Pałacowy". rudy-opactwo.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- "Plans and designs of the Rudy palace around 1860 at the Architekturmuseum in Berlin". architekturmuseum.ub.tu-berlin.de (in German). Retrieved 5 May 2024.

Gallery: A tour of the ducal palace in the 1920s

[edit]- Vestibule

- Staircase hall

- Room above the staircase

- Ducal study

- Ducal study

- Grand hall

- Grand hall

- Library

- Library

- Dining room

- Dining room

- Palace corridor

- Palace corridor

- Garden front of the palace

- The palace seen from the park

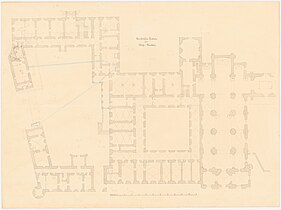

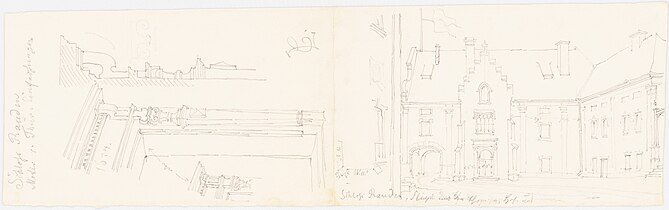

Gallery: Plans and designs of Rudy palace from around 1860 at the Berlin Architekturmuseum

[edit]- Rudy palace by Lüdecke Carl Johann Bogislaw (1826–1894)

- Palace floor plan of the ground floor; Water supply highlighted blue, scale strip without scale, references to other leaves of the construction recording

- Western courtyard facade of the palace

- Northern courtyard facade of the palace

- East courtyard facade of the palace

- Southern courtyard facade of the palace

- Facade to the park, left wing; Facade to the street, right wing

- Eastern facade to the park

- Proposal for the palace court year by Lüdecke Carl Johann Bogislaw (1826–1894)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch