SMS Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden's sister ship Frankfurt | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | SMS Wiesbaden |

| Namesake | Wiesbaden |

| Ordered | 29 June 1913 |

| Builder | A.G. Vulcan |

| Laid down | 10 November 1913 |

| Launched | 30 January 1915 |

| Commissioned | 23 August 1915 |

| Fate | Sunk at the Battle of Jutland, 1 June 1916 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Wiesbaden-class light cruiser |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 145.30 m (476 ft 8 in) |

| Beam | 13.90 m (45 ft 7 in) |

| Draft | 5.76 m (18.9 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) |

| Range | 4,800 nmi (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Crew |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Wiesbaden[a] was a light cruiser of the Wiesbaden class built for the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine). She had one sister ship, SMS Frankfurt; the ships were very similar to the previous Karlsruhe-class cruisers. The ship was laid down in 1913, launched in January 1915, and completed by August 1915. Armed with eight 15 cm SK L/45 guns, Wiesbaden had a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) and displaced 6,601 t (6,497 long tons; 7,276 short tons) at full load.

Wiesbaden saw only one major action, the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916. The ship was badly damaged by gunfire from the battlecruiser HMS Invincible. Immobilized between the two battle fleets, Wiesbaden became the center of a hard-fought action that saw the destruction of two British armored cruisers. Heavy fire from the British fleet prevented evacuation of the ship's crew. Wiesbaden remained afloat until the early hours of 1 June and sank sometime between 01:45 and 02:45. Only one crew member survived the sinking; the wreck was located by German Navy divers in 1983.

Design

[edit]The Wiesbaden-class cruisers were a development of the preceding Graudenz-class cruisers, but the budgetary constraints imposed by the need to pass the 1912 Naval Law no longer applied. This freed the design staff to adopt the new 15 cm (5.9 in) gun for the new ship's main battery, which the German fleet had sought for some time. The decision to move to the larger gun was in large part driven by reports that the latest British cruiser, HMS Chatham, would carry a complete waterline armor belt.[1]

Wiesbaden was 145.30 meters (476 ft 8 in) long overall and had a beam of 13.90 m (45 ft 7 in) and a draft of 5.76 m (18 ft 11 in) forward. She displaced 6,601 t (6,497 long tons; 7,276 short tons) at full load. The ship had a fairly small superstructure that consisted primarily of a conning tower forward. She was fitted with a pair of pole masts, the fore just aft of the conning tower and the mainmast further aft. Her hull had a long forecastle that extended for the first third of the ship, stepping down to main deck level just aft of the conning tower, before reducing a deck further at the mainmast for a short quarterdeck. Wiesbaden had a crew of 17 officers and 457 enlisted men.[2]

Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of Marine steam turbines driving two 3.5-meter (11 ft) screw propellers. Steam was provided by ten coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers and two oil-fired double-ended boilers, which were vented through three funnels. The ship's engines were rated to produce 31,000 shaft horsepower (23,000 kW), which gave the ship a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). Wiesbaden carried 1,280 t (1,260 long tons) of coal, and an additional 470 t (460 long tons) of oil that gave her a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[2]

The ship was armed with a main battery of eight 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, four were located amidships, two on either side, and two were placed in a superfiring pair aft. The guns could engage targets out to 17,600 m (57,700 ft). They were supplied with 1,024 rounds of ammunition, for 128 shells per gun. The ship's antiaircraft armament initially consisted of four 5.2 cm (2 in) L/55 guns, though these were replaced with a pair of 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns. She was also equipped with four 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes with eight torpedoes. Two were submerged in the hull on the broadside and two were mounted on the deck amidships. She could also carry 120 mines.[3]

The ship was protected by a waterline armor belt that was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick amidships. Protection for the ship's internals was reinforced with a curved armor deck that was 60 mm thick; the deck sloped downward at the sides and connected to the bottom edge of the belt armor. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides.[3]

Service history

[edit]Named for the eponymous city, Wiesbaden was ordered on 29 June 1913 under the contract name "Ersatz Gefion"[b] and was laid down at the AG Vulcan shipyard in Stettin on 10 November that year. She was launched on 30 January 1915 without ceremony owing to World War I, after which fitting-out work commenced. She was commissioned into active service on 23 August 1915 to begin sea trials, which were rushed to prepare the ship for wartime service. Her commander was Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Captain) Fritz Reiß. The ship ran her measured mile test in the shallow waters of the Little Belt, during which she reached a speed of 27.4 knots (50.7 km/h; 31.5 mph), though this would have equated to about 29 knots (54 km/h; 33 mph) in deep-water steaming. After completing her initial testing on 23 October, she was assigned to II Scouting Group, part of the reconnaissance force of the High Seas Fleet. The ship then went into the Baltic Sea for individual training until 1 December to work the crew up for combat operations.[4][5][6]

After joining her unit, she joined the other cruisers for a sweep into the Skagerrak and Kattegat from 16 to 18 December. The next three months passed uneventfully, and she went to sea again on 5 March 1916 for a patrol in the North Sea that concluded without note the following day. Another sweep into the North Sea followed on 25–26 March, which also ended without encountering British vessels. Wiesbaden and the rest of II Scouting Group sortied on 31 March in response to distress signals from the zeppelin L 13, but the zeppelin was able to return to Germany, allowing the ships to return to port on 1 April. II Scouting Group conducted another sweep into the North Sea on 21–22 April in the direction of Horns Rev.[7]

Two days later, Wiesbaden sortied to participate in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April.[8] On the approach to Lowestoft, the cruisers Elbing and Rostock spotted the Harwich Force, a squadron of three light cruisers and eighteen destroyers, approaching the German formation from the south at 04:50. Konteradmiral (KAdm–Rear Admiral) Friedrich Boedicker, the German commander, initially ordered his battlecruisers to continue with the bombardment, while Wiesbaden and the other five light cruisers concentrated to engage the Harwich Force. At around 05:30, the British and German light forces clashed, firing mostly at long range. The battlecruisers arrived on the scene at 05:47, prompting the British squadron to retreat at high speed. A British light cruiser and destroyer were damaged before Boedicker broke off the engagement after receiving reports of submarines in the area.[9] On 3 May, Wiesbaden searched for the zeppelin L 20, but failed to locate the airship.[8]

Battle of Jutland

[edit]

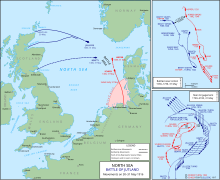

The next major fleet operation began on 31 May with the sortie of the entire High Seas Fleet, including Wiesbaden and II Scouting Group. The operation resulted in the Battle of Jutland later that day and into 1 June.[10] Wiesbaden's sister ship Frankfurt served as Boedicker's flagship. The unit was assigned to screen for the battlecruisers of Vizeadmiral Franz von Hipper's I Scouting Group. At the start of the battle, Wiesbaden was cruising to starboard, which placed her on the disengaged side when Elbing, Pillau, and Frankfurt first engaged the British cruiser screen.[11]

At around 18:30,[c] Wiesbaden and the rest of II Scouting Group encountered the cruiser HMS Chester; they opened fire and scored several hits on the ship. As both sides' cruisers disengaged, Rear Admiral Horace Hood's three battlecruisers intervened. His flagship HMS Invincible scored a hit on Wiesbaden that exploded in her engine room and disabled the ship. KAdm Paul Behncke, the commander of the leading element of the German battle line, ordered his dreadnoughts to cover the stricken Wiesbaden. Simultaneously, the light cruisers of the British 3rd and 4th Light Cruiser Squadrons attempted to make a torpedo attack on the German line; while steaming into range, they battered Wiesbaden with their main guns. The destroyer HMS Onslow steamed to within 2,000 yards (1,800 m) of Wiesbaden and fired a single torpedo at the crippled cruiser. It hit directly below the conning tower, but the ship remained afloat. In the ensuing melee, the armored cruiser HMS Defence blew up and HMS Warrior was fatally damaged.[12] Wiesbaden launched her torpedoes while she remained immobilized, scoring one hit against the battleship HMS Marlborough.[13]

Shortly after 20:00, III Flotilla of torpedo boats attempted to rescue Wiesbaden's crew, but heavy fire from the British battle line drove them off.[14] Another attempt to reach the ship was made, but the torpedo boat crews lost sight of the cruiser and were unable to locate her. The ship finally sank sometime between 01:45 and 02:45. Only one crew member survived the sinking; he was picked up by a Norwegian steamer the following day.[15] Among the 589 killed was the well-known writer of poetry and fiction dealing with the life of fishermen and sailors, Johann Kinau, known under his pseudonym of Gorch Fock, who has since then been honored by having two training windjammers of the Kriegsmarine and the German Navy, respectively, named after him.[16][17][18] The wreck of Wiesbaden was found in 1983 by divers of the German Navy, who removed both of the ship's screws. The ship lies on the sea floor upside down, and was the last German cruiser sunk at Jutland to be located.[19]

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

- ^ The times mentioned in this section are in CET, which is congruent with the German perspective. This is one hour ahead of UTC, the time zone commonly used in British works.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Dodson & Nottelmann, pp. 150–152.

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 111.

- ^ a b Gröner, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Dodson & Nottelmann, p. 153.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 82.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 162.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 83.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Bennett, p. 222.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 62, 70, 96.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 127–128, 137–141.

- ^ Campbell, p. 164.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 214, 294–295.

- ^ Gröner, p. 112.

- ^ Furness & Humble, p. 87.

- ^ Hadley, p. 65.

- ^ Thomas Nielsen (2010). "Battle of Jutland 2010". No Limits Diving. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

References

[edit]- Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Classics. ISBN 978-1-84415-300-8.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.

- Furness, Raymond & Humble, Malcolm (1997). A Companion to Twentieth-century German Literature. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15057-4.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hadley, Michael L. (1995). Count Not The Dead: The Popular Image of the German Submarine. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-7735-1282-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 8. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch