Siege of Baghdad

| Siege of Baghdad | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions and conquests | |||||||||

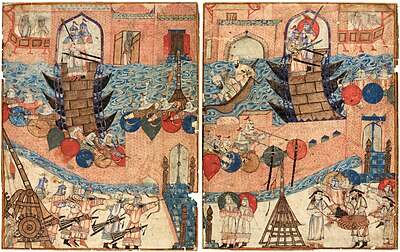

Depiction of Hulegu's army besieging the city, c. 1430 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Ilkhanate (Mongol Empire) | Abbasid Caliphate | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 138,000–300,000,[a] including auxiliaries from Armenia, Georgia, China and elsewhere | 50,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 200,000 killed (according to Hulegu) 800,000–2,000,000 killed (Muslim sources) | |||||||||

The Siege of Baghdad took place in early 1258. A large army commanded by Hulegu, a prince of the Mongol Empire, attacked the historic capital of the Abbasid Caliphate after a series of provocations from its ruler, caliph al-Musta'sim. Within a few weeks, Baghdad fell and was sacked by the Mongol army—al-Musta'sim was killed alongside hundreds of thousands of his subjects. The city's fall has traditionally been seen as marking the end of the Islamic Golden Age; in reality, its ramifications are uncertain.

After the accession of his brother Möngke Khan to the Mongol throne in 1251, Hulegu, a grandson of Genghis Khan, was dispatched westwards to Persia to secure the region. His massive army of over 138,000 men took years to reach the region but then quickly attacked and overpowered the Nizari Ismaili Assassins in 1256. The Mongols had expected al-Musta'sim to provide reinforcements for their army—the Caliph's failure to do so, combined with his arrogance in negotiations, convinced Hulegu to overthrow him in late 1257. Invading Mesopotamia from all sides, the Mongol army soon approached Baghdad, routing a sortie on 17 January 1258 by flooding their opponents' camp. They then invested Baghdad, which was left with around 30,000 troops.

The assault began at the end of January. Mongol siege engines breached Baghdad's fortifications within a couple of days, and Hulegu's highly-trained troops controlled the eastern wall by 4 February. The increasingly desperate al-Musta'sim frantically tried to negotiate, but Hulegu was intent on total victory, even killing soldiers who attempted to surrender. The Caliph eventually surrendered the city on 10 February, and the Mongols began looting three days later. The total number of people who died is unknown, as it was likely increased by subsequent epidemics; Hulegu later estimated the total at around 200,000. After calling an amnesty for the pillaging on 20 February, Hulegu executed the caliph. In contrast to the exaggerations of later Muslim historians, Baghdad prospered under Hulegu's Ilkhanate, although it did decline in comparison to the new capital, Tabriz.

Background

[edit]

Baghdad was founded in 762 by al-Mansur, the second caliph of the Abbasid dynasty, which had recently overthrown the empire of the Umayyads. Al-Mansur believed that the new Abbasid Caliphate needed a new capital city, located away from potential threats and near the dynasty's power base in Persia. Incredibly wealthy due to the trade routes and taxes it controlled, Baghdad quickly became a world city and the epicentre of the Islamic Golden Age: poets, writers, scientists, philosophers, musicians, and scholars of every type thrived in the city. Containing centres of learning like the House of Wisdom and astronomical observatories, which used the newly-arrived technology of paper and the gathering of the teachings of antiquity from all Eurasia, Baghdad was "the intellectual capital of the planet", in the words of the historian Justin Marozzi.[1]

During the tenth century, the Abbasids gradually decreased in power. This culminated in Baghdad being occupied, first by the Buyids in 945 and then the Seljuks in 1055, by which time the caliphs had only local authority. They focused their attentions on Baghdad itself, which retained its position as one of the preeminent cities of the world—it was joined only by Kaifeng and Hangzhou in having over a million inhabitants between 1000 and 1200.[2] The caliphate reemerged as a significant power under al-Nasir (r. 1180–1225), who saw off threats from the last Seljuk rulers and their successors, the Khwarazmians. Muhammad II of Khwarazm's 1217 invasion of the Abbasids failed, and his realm was soon invaded by the armies of Genghis Khan, first ruler of the Mongol Empire.[3]

After the Mongol invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire ended in late 1221, they did not return to the region until 1230. In that year, Chormaqan, a leading general under Genghis' successor Ögedei Khan, arrived in Azerbaijan to eliminate the Khwarazmian prince Jalal al-Din, who was killed the following year.[4] Thereafter, Chormaqan began to establish Mongol hegemony in northwestern Iran and the Transcaucasus. After they captured Isfahan in 1236, the Mongols began to test caliphal authority in Mesopotamia, besieging Irbil in 1237 and raiding up to the walls of Baghdad itself the following year.[5] Chormaqan and his 1241 replacement Baiju thereafter raided the region nearly every year. Although Mongol rule was secured elsewhere in the Near East—their victory at the 1243 Battle of Köse Dağ reduced the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum to a client state—Baghdad remained unconquered, and even defeated a Mongol force in 1245.[6] Another problem was the secretive Nizari Ismaili state, also known as the Order of Assassins, in the Elburz Mountains. They had killed Mongol commanders during the 1240s, and had allegedly dispatched 400 Assassins to the Mongol capital Karakorum to kill the khan himself.[7]

Campaign against the Assassins

[edit]Möngke Khan was proclaimed khan in 1251 as part of the Toluid Revolution, which established the family of Genghis' youngest son Tolui as the most powerful figures in the Mongol Empire.[8] Möngke resolved to send his younger brothers Kublai and Hulegu on massive military expeditions to subdue rebellious vassals and problematic enemies. While Kublai was sent to vassalize the Dali Kingdom and resume the war against the Southern Song, Hulegu was dispatched westwards to destroy the Ismaili Assassins and to ensure the submission of the Abbasid caliphs.[9] For this task, he was assigned one fifth of the empire's manpower, a figure which has been variously calculated by modern scholars as between 138,000, nearly 200,000, or 300,000 men.[a] The force contained troops from vassalized Armenia, including its king Hetoum I, a thousand-strong corps of military engineers led by Guo Kan, auxiliaries from all over the empire, and generals from all the branches of the Mongol imperial family, including three princes from the Golden Horde, the Chagatayid prince Teguder, and possibly one of Genghis Khan's grandsons through his daughter Checheikhen.[13]

Because of the size of his force, Hulegu's progress from Karakorum was extremely leisurely by Mongol standards. Setting out in October 1253, he spent the next years passing through Transoxiana and received homage from local rulers, including Arghun Aqa at Kish in November 1255; early the following year, he entered the Assassins' heartland of Kohistan.[14] An advanced vanguard under the general Kitbuqa had taken numerous Ismaili fortresses, unsuccessfully besieged the stronghold at Gerdkuh, and sacked the city of Tun between 1253 and 1256.[15] The Grand Master of the Assassins, Ala ad-Din Muhammad, had died in December 1255, and Hulegu sent ambassadors to his young successor, Rukn al-Din Khurshah. The new Grand Master attempted to stall for time, but his fortresses steadily fell to the Mongols and he surrendered from Maymun-Diz on 19 November 1256.[16] Rukn al-Din persuaded the stronghold of Alamut to surrender on 15 December.[17][b]

Baghdad campaign

[edit]Hulegu had expected the Abbasid caliph al-Musta'sim to provide troops for the campaign against the Assassins; the caliph had initially assented, but his ministers argued that the real purpose of the request was to empty Baghdad of potential defenders, and so he refused.[19] Later Sunni writers accused Baghdad's vizier, a Shi'ite named Muhammad ibn al-Alqami, of having betrayed the caliph by opening secret negotiations with Hulegu. In 1256, sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi'a had broken out after a devastating flood, placing Baghdad in a difficult position; however, al-Musta'sim and his ministers were still quite delusional concerning their chances of success.[20]

...I will bring you crashing down from the summit of the sky,

Like a lion I will throw you down to the lowest depths.

I will not leave a single person alive in your country,

I will turn your city, lands and empire into flames.If you have the heart to save your head and your ancient family,

Listen carefully to my advice.

If you refuse to accept it, I will show you the meaning of the will of God.

Hulegu spent the summer of 1257 on or near the Hamadan plain, where he was rejoined by Baiju, who had been subduing restless vassals in the northwest. Baiju brought Seljuk, Georgian, and Armenian vassals, including the princes Pŕosh Khaghbakian and Zak‘arē, to join the Mongol army. In September, Hulegu began a correspondence with al-Musta'sim, described by the historian René Grousset as "one of the most magnificent dialogues in history".[22] His first message demanded that the caliph peacefully submit and send his three principal ministers—the vizier, the commander of the soldiers, and the dawatdar (keeper of the inkpot)—to the Mongols; all three likely refused, and three less important officials were sent instead.[23]

Al-Musta'sim's reply to Hulegu's letter called the Mongol leader young and ignorant, and presented himself as able to summon armies from all of Islam. Accompanied by disrespectful behaviour towards Hulegu's envoys, who were exposed to taunting and mockery from mobs on Baghdad's streets, this was just antagonistic bombast: the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt was hostile towards the caliph, while the Ayyubid minor rulers in Syria were focusing on their own survival.[24] A further exchange of letters brought no progress save the caliph's concession of a small amount of tribute—al-Alqami had argued for sending large amounts, but the dawatdar argued that al-Alqami was trying to empty the treasury and win Hulegu's favour.[25]

Losing patience, Hulegu consulted his advisors on the practicalities of attacking Baghdad. The astronomer Husam al-Din prophesied doom, stating that all rulers who had attacked Baghdad had afterwards lost their kingdom. Hulegu then turned to the polymath Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, who simply replied that none of these disasters would happen, and that Hulegu would rule in place of the caliph.[26]

Advance and siege

[edit]Flanked on the right wing by the Golden Horde princes, who approached via the Shahrizor plain, and on the left by Kitbuqa in Khuzistan, Hulegu commanded the main Mongol force and sacked Kermanshah on 6 December. After a council of war in mid-December, his commanders dispersed to carry out different tasks.[27] Baiju returned to the vanguard at Irbil, and crossing the Tigris at Mosul with the help of its emir Badr al-Din Lu'lu', who also provided supplies,[28] headed southwards towards Baghdad. Baiju reached the Nahr Isa canal in mid-January 1258, whereupon his deputy Sughunchaq pushed the advance party to around 25 miles (40 km) from the city.[29] On 16 January, Sughunchaq was confronted by the dawatdar with 20,000 infantry and forced to retreat; the caliphal army pursued, but that night Baiju's forces broke the dykes of the Dujayl Canal and flooded the camp of the celebrating Abbasid army. Many drowned, and the remainder were engaged by Baiju's army the following morning—they were routed and only a few, including the dawatdar, made it back to Baghdad.[30]

Meanwhile, Kitbuqa had crossed the Tigris to the south and was approaching the Karkh suburbs, while Hulegu himself reached the eastern suburbs on 22 January, where he was welcomed by the local Shi'ites. The Mongols then closely invested Baghdad by erecting a palisade around the whole city and digging a moat inside this circumvallation; these fortifications were completed within a day.[31] They constructed mounds out of bricks for their mangonels and ballistae and prepared their ammunition—the Mongols used palm trees and stones previously used in building the suburbs until they found suitable rocks in the Jebel Hamrin mountains, three days transport away. They also used pyrotechnics such as burning naphtha.[32] To prevent anyone from using the Tigris to escape, Hulegu ordered the construction of pontoon bridges across the river on both sides of the city. Despite Baghdad's frailty—the flood-weakened walls were in disrepair and the garrison, at most 50,000 strong before the dawatdar's sortie, was untrained and largely incapable—Hulegu meticulously planned his operations to cover all eventualities.[33]

The assault on Baghdad's walls began on either 29[34] or 30 January.[35] The Mongol forces arrowed messages containing guarantees of safety into the city—those covered by the guarantees included Christians, certain Muslim figures, and those who had not fought the Mongols or who had surrendered.[36] The first breach was made in the southeast Ajami tower, near Hulegu's camp, on 1 February, but the Mongols were driven back; further breaches over the next two days enabled them to access and seize control of the east battlements by 4 February.[37] Sensing defeat, the dawatdar attempted to escape by sailing down the Tigris, but Hulegu's preparations held and forced him back into the city with a loss of three ships.[38]

Caliph al-Musta'sim sent out numerous envoys, including al-Alqami and Makkikha II, Patriarch of the Church of the East, during the next week, but Hulegu was determined on nothing less than unconditional surrender, especially after one of his commanders was wounded by an arrow during a parley.[39] Both the dawatdar and the commander of Baghdad's garrison were surrendered to the Mongols during the negotiations, and were now put to death.[40] On 7 February, a large number of unarmed soldiers and inhabitants emerged from the city, in the apparent hope that they would be spared and allowed to settle in Syria; instead, they were divided into groups and executed.[41]

With limited options, al-Musta'sim prepared to surrender. After sending out an embassy led by his son and heir Ahmed, who secured guarantees of safety for his family, the caliph surrendered on 10 February, bringing his family and 3,000 dignitaries. Hulegu asked al-Musta'sim to order the population of the city to leave the city after laying their weapons down; those who obeyed were slaughtered.[42] The caliph and his family were housed near Kitbuqa's forces near the southern gate.[43]

Sack and aftermath

[edit]

On 13 February, the sack of Baghdad began. This was not an act of wanton destruction, as it has commonly been presented, but rather a calculated decision to show the consequences of defying the Mongol Empire.[44] Sayyids, scholars, merchants who traded with the Mongols, and the Christians in the city on whose behalf Hulegu's wife Doquz Khatun, herself a Christian, had interceded, were deemed worthy and were instructed to mark their doors so their houses would be spared.[45] The rest of the city was subject to pillaging and killing for a full week. According to Kirakos Gandzaketsi, a 13th-century Armenian historian, the Christians in Hulegu's army took special pleasure in Baghdad's sack.[46]

It is unknown how many inhabitants were killed: later Muslim writers estimated between 800,000 and two million deaths, while Hulegu himself, in a letter to Louis IX of France, noted that his army had killed 200,000.[47] Figures may have been inflated by a subsequent epidemic among the survivors; scholars have debated whether this was an outbreak of plague, a precursor to the Black Death.[48] Mongol military logistics demanded that pounded millet be transported from the Mongol heartland all the way to Iraq, providing ample opportunity for plague-bearing fleas to flourish on rats, before the supplies were distributed among the vulnerable survivors of the siege. A physician who was present recorded that a "pestilence" killed so many refugees that their bodies could not be buried and were thrown into the Tigris.[49] Hulegu had moved camp five times in early 1257 for no discernible military reason; the historian Monica Green has suggested that he sought to escape outbreaks of plague.[50]

Two days into the looting, on 15 February, Hulegu visited the caliphal palace and forced al-Musta'sim to reveal his treasures; some was distributed among commanders such as Guo Kan, but most loaded onto wagons and transported either to Möngke Khan in Karakorum or to Shahi Island in Azerbaijan, where Hulegu would be buried. Having granted the palace to Makkikha to be a church, Hulegu then held a celebratory banquet in which he mockingly played host to the caliph. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, who was likely present, recorded the following dialogue:[51]

[Hulegu] set a golden tray before the Caliph and said: "Eat!"

"It is not edible," said the Caliph.

"Then why did you keep it," asked the khan, "and not give it to your soldiers? And why did you not make these iron doors into arrow-heads and come to the bank of the river so that I might not have been able to cross it?"

"Such", replied the Caliph, "was God's will."

"What will befall you," said the khan, "is also God's will."

This incident is likely the source of a folktale, reproduced in the writings of Christian writers such as Marco Polo, in which Hulegu subsequently locked al-Musta'sim in a cell surrounded by his treasures, whereupon he starved to death in four days.[52] In reality, on 20 February, after Hulegu had halted the plundering and killing and moved his camp away from the city to escape the increasingly putrid air, al-Musta'sim was executed alongside his whole family and court. To avoid spilling a royal's blood, a great taboo for the Mongols, the caliph was wrapped in a rolled-up carpet and trampled to death by horses.[53] Hulegu had debated whether to put al-Musta'sim to death at all, but eventually decided on doing so to break the myth of the caliphate being an all-powerful, invulnerable, and inviolate entity.[54]

If, as later writers allege, al-Alqami had betrayed Baghdad to the Mongols, Hulegu would have had him executed—such was the Mongol policy regarding all traitors. Instead, because of his efforts to dissuade the caliph from a foolish path, he was reappointed to the vizierate, although he died less than three months later.[55] Having also appointed a Khwarazmian daruyachi ('overseer official') named Ali Ba'atar for the region and stationed 3,000 soldiers in the city, Hulegu gave instructions to rebuild Baghdad and to open its bazaars. On 8 March, he left the area, travelling northwards to Hamadan and then Azerbaijan, where he remained for a year.[56]

Legacy

[edit]The fall of Baghdad marked the end of the five hundred-year-old Abbasid Caliphate—although a member of the dynasty eventually made it to Cairo, where the Mamluks installed him as Al-Mustansir II, he and his descendants were puppets of the Mamluk state and never gained much recognition in the wider Muslim world; they would later be usurped by the Ottomans, who maintained the title of caliph up to the 20th century.[57] It also marked a shift of power away from Baghdad and towards cities like Tabriz, the capital of the Ilkhanate, the khanate founded by Hulegu in the aftermath of the siege.[58]

Baghdad's fall was not as era-defining as has been suggested, although the end of the caliphate marked a momentous occasion for the Islamic world.[59] Muslim writers have traditionally ascribed the decline of the Islamic Golden Age, and consequently the subsequent rise of the Western world, to this one event; however, such an argument has been criticized by modern historians as simplistic and lazy.[60] Whereas an oft-quoted description from a 16th-century historian details that so many books from Baghdad's libraries were thrown into the Tigris that "the colour of the river changed into black from their multitude," the historian Michal Biran has shown that large libraries reopened for learning and teaching within two years of the siege.[61] Hulegu and his successors as rulers of the Ilkhanate actively patronized and encouraged musical and literary traditions; according to Biran it was subsequent sieges like those conducted by Timur in 1393 and 1401 and by the Ottomans in 1534 that ensured the city's long-term marginalization.[62]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b John Masson Smith estimated 170,000 Mongol troops in addition to 130,000 auxiliaries in 1975;[10] James Chambers estimated close to 200,000 troops in 1979;[11] and Timothy May estimated around 138,000 in 2007.[12]

- ^ Some other fortresses refused; Lambasar fell in late 1257, while Gerdkuh held out for fifteen years, only falling in 1271. Although Hulegu appears to have quite liked Rukn al-Din and honoured his safety, Möngke viewed his continued survival as a waste of resources and ordered him put to death.[18]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Marozzi 2014, chapters 1, 3.

- ^ Marozzi 2014, chapter 4; Modelski 2007.

- ^ Boyle 1968, pp. 200–202; Atwood 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Jackson 2017, pp. 81–82; Atwood 2004, p. 2; Boyle 1968, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Jackson 2017, pp. 82–83; Atwood 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Jackson 2017, pp. 83–85; Atwood 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 125; Atwood 2004, p. 255; Morgan 1986, p. 130; Biran 2012, pp. 78–79.

- ^ May 2018, pp. 144–145; Atwood 2004, p. 363.

- ^ May 2018, p. 159; Jackson 2017, p. 125; Boyle 1968, p. 340; Lane 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Smith 1975, pp. 277–278.

- ^ Chambers 1979, pp. 142–143.

- ^ May 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Lane 2003, pp. 18–19; Hodous 2020, p. 30; Atwood 2004, p. 255; Jackson 2017, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Boyle 1968, p. 341; Jackson 2017, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Boyle 1968, p. 342; May 2018, p. 163; Atwood 2004, p. 255.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 255; Lane 2003, pp. 24–25; Jackson 2017, p. 127; Boyle 1968, pp. 342–344.

- ^ Boyle 1968, pp. 344–345; Jackson 2017, p. 127.

- ^ Lane 2003, pp. 25–26; Atwood 2004, pp. 255–256.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 128; Lane 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Lane 2003, pp. 31–35; Marozzi 2014, chapter 5; Atwood 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Marozzi 2014, chapter 5.

- ^ Chambers 1979, p. 143; Boyle 1968, pp. 345–346; Bai︠a︡rsaĭkhan 2011, p. 129.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 128; Lane 2003, p. 30; Boyle 1968, p. 346.

- ^ Marozzi 2014, chapter 5; Chambers 1979, p. 144; Lane 2003, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 128; Chambers 1979, p. 144.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 129; Boyle 1968, p. 346.

- ^ Boyle 1968, pp. 346–347; Jackson 2017, p. 128.

- ^ Bai︠a︡rsaĭkhan 2011, p. 129

- ^ Boyle 1968, p. 347; Atwood 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Boyle 1968, p. 347; Atwood 2004, p. 28; Chambers 1979, p. 144.

- ^ Boyle 1968, pp. 347–348; Chambers 1979, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Chambers 1979, p. 145; Buell 2003, pp. 51–52; Marozzi 2014, chapter 5.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 28; Chambers 1979, p. 144; Marozzi 2014, chapter 5.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 2; Buell 2003, p. 51; Boyle 1968, p. 348.

- ^ Chambers 1979, p. 145; Marozzi 2014, chapter 5.

- ^ Lane 2003, p. 32; Chambers 1979, p. 145.

- ^ Buell 2003, p. 52; Atwood 2004, pp. 28–29; Boyle 1968, p. 348.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 29; Boyle 1968, p. 348; May 2018, p. 166.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 28; Chambers 1979, p. 145; Boyle 1968, p. 348.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 128; Boyle 1968, p. 348.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 167; Chambers 1979, p. 145.

- ^ Boyle 1968, p. 348; Jackson 2017, p. 167; Atwood 2004, p. 29; Marozzi 2014, chapter 5.

- ^ Boyle 1968, p. 348.

- ^ Biran 2016, p. 140; Lane 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 167; Atwood 2004, p. 226.

- ^ Chambers 1979, p. 145; Marozzi 2014, chapter 5; Biran 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Morgan 1986, p. 133; Buell 2003, p. 117; Atwood 2004, p. 344; Chambers 1979, p. 146.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 172; Brack, Biran & Amitai 2024.

- ^ Green 2020, pp. 1621–1623; Frankopan 2024, p. 294.

- ^ Green 2020, p. 1627; Frankopan 2024, p. 294.

- ^ Boyle 1968, pp. 348–349; Chambers 1979, p. 145; Atwood 2004, p. 226; Hodous 2020, p. 35.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 129; Morgan 1986, p. 133; Boyle 1968, p. 348; May 2018, p. 166.

- ^ Jackson 2017, pp. 128–129; Atwood 2004, p. 29; Morgan 1986, p. 133.

- ^ Biran 2012, p. 79; Jackson 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Lane 2003, pp. 34–35; Boyle 1968, p. 349; Chambers 1979, p. 145.

- ^ Boyle 1968, p. 349; Atwood 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Morgan 1986, pp. 133–134; Jackson 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Biran 2012, p. 99; Atwood 2004, p. 2; Lane 2022, p. 283.

- ^ Jackson 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Biran 2019, p. 465; Al-Khalili 2012, chapter 12: Decline and Renaissance.

- ^ Biran 2019, pp. 470–472.

- ^ Biran 2016, p. 150; Biran 2019, pp. 494–495.

Bibliography

[edit]- Al-Khalili, Jim (2012). The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-1431-2056-8.

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Bai︠a︡rsaĭkhan, D. (2011). The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9-0041-8635-4. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h10n.

- Biran, Michal (2012). Genghis Khan. Makers of the Muslim World. London: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-7807-4204-5.

- Biran, Michal (2016). "Music in the Mongol Conquest of Baghdad: Ṣafī al-Dīn Urmawī and the Ilkhanid Circle of Musicians". In De Nicola, Bruno; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Mongols' Middle East: Continuity and Transformation in Ilkhanid Iran. Islamic History and Civilization. Vol. 127. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9-0043-1199-2.

- Biran, Michal (2019). "Libraries, Books, and Transmission of Knowledge in Ilkhanid Baghdad". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 62 (2–3): 464–502. doi:10.1163/15685209-12341485. JSTOR 26673137.

- Boyle, John Andrew (1968). "Dynastic and Political History of the Il-khans". In Boyle, J. A. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 303–421. ISBN 978-1-139-05497-3.

- Brack, Jonathan; Biran, Michal; Amitai, Reuven (2024). "Plague and the Mongol conquest of Baghdad (1258)? A reevaluation of the sources". Medical History: 1–19. doi:10.1017/mdh.2023.38. PMC 11949627.

- Buell, Paul D. (2003). Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4571-8.

- Chambers, James (1979). The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-6891-0942-3.

- Frankopan, Peter (2024). The Earth Transformed: An Untold History. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5266-2257-0.

- Green, Monica H. (2020). "Four Black Deaths". The American Historical Review. 125 (5): 1601–1631. doi:10.1093/ahr/rhaa511.

- Hodous, Florence (2020). "Guo Kan: Military Exchanges between China and the Middle East". In Biran, Michal; Brack, Jonathan; Fiaschetti, Francesca (eds.). Along the Silk Roads in Mongol Eurasia: Generals, Merchants, and Intellectuals (1st ed.). Oakland: University of California Press. pp. 27–43. ISBN 978-0-520-29875-0. JSTOR j.ctv125jrx5.7.

- Jackson, Peter (2017). The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-3001-2533-7.

- Lane, George (2003). Early Mongol Rule in Thirteenth-Century Iran: A Persian Renaissance. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4152-9750-9.

- Lane, George (2022). "The Ilkhanate". In May, Timothy; Hope, Michael (eds.). The Mongol World. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 279–297. ISBN 978-1-3151-6517-2.

- Marozzi, Justin (2014). Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood. London: Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-1419-4804-1.

- May, Timothy (2007). The Mongol Art of War: Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Military System. Yardley: Westholme. ISBN 978-1-5941-6046-2.

- May, Timothy (2018). The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4237-3.

- Modelski, George (29 September 2007). "Central Asian world cities? (XI – XIII century) A discussion paper". Archived from the original on 30 April 2011.

- Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-6311-7563-6.

- Smith, John Masson (1975). "Mongol Manpower and Persian Population". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 18 (3): 271–299. doi:10.2307/3632138. JSTOR 3632138.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch