San Jose electric light tower

The San Jose electric light tower, also known as Owen's Electric Tower after its creator and chief booster, was constructed in 1881 at an intersection in downtown San Jose, California, as a "high light" or moonlight tower to light the city using arc lights. A pioneer use of electricity for municipal lighting, it was later strung with incandescent bulbs and was destroyed in a storm in December 1915. A half-size replica stands at History Park at Kelley Park.

History

[edit]The electric light tower was proposed by J. J. Owen, publisher of the San Jose Mercury, the precursor of The Mercury News, as a way of lighting the entire center of San Jose on the "high light" principle, at less expense than gas street lighting. Owen was inspired by the electric lighting in San Francisco, the first in the world, which he had visited in 1879. He designed the tower, estimating that it would require $5,000[1] and one month to build it. Just under $3,500 was raised by public subscription, and groundbreaking took place on August 11, 1881. The tower was dedicated on December 13 the same year. The San Jose Mercury boasted that San Jose was the first town west of the Rockies lighted by electricity,[2] which was an erroneous claim considering San Francisco, the city that Owens took originally took his inspiration for the moon light from, had already been lighted by electricity several years prior.[3]

Design

[edit]

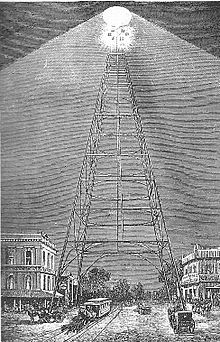

As built, the tower was 207 feet (63 m) tall, topped by a platform holding six arc lamps with a diffusing and protective shield above them and a 30 ft (9.1 m) flagpole[4] for a total height of 237 feet (72 m) and a total of 24,000 candlepower. It stood on a brick foundation and spanned the intersection of Santa Clara and Market Streets.[5] It was made of hollow iron pipe and braced with iron hoops. Owen modeled it on the moonlight tower built earlier in 1881 in Akron, Ohio, widening the base to 75 feet (23 m) square[6] so that supporting cables would not be needed; the Akron tower collapsed when the cables broke. Electrical equipment and power were supplied by the California Electric Light Company, which had been incorporated by George H. Roe to market the products of Charles Brush's Brush Electric Company. Brush's patented system made it possible to connect arc lamps in series. The generator was located in a steam-powered planing mill, using its steam power during the night hours.

The tower was possibly the world's tallest free-standing iron structure at the time. Its light was visible as far away as San Francisco;[7] it was brighter than expected, more like full moonlight, and a farmer outside San Jose complained that it interfered with his laying hens by confusing them.[8] The Sacramento Union reported the light was bright enough to throw distinct shadows 1 mile (1.6 km) away and from 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) it was as bright as the half moon.[9][5] Nearby businesses named themselves after it, and the police on the local beat made money selling birds that collided with the tower to local restaurants. Christmas lights and banners were hung from it, and photographers used it as a bird's eye vantage point. It was featured in an article in Harper's Weekly[6] and was praised in La Lumière Électrique, a French electrical journal. A newspaper in Santa Barbara, California called it "a complete success" and "the favorite electric tower of the world".[10]

It has been argued that its design influenced that of the Eiffel Tower, which was built eight years later; in 1989 the City of San Jose sued in a mock trial the estate of Gustave Eiffel and the City of Paris for copyright infringement of the San Jose design, the mock trial judge - Marcel Poche - at the University of Santa Clara determining that the idea in Paris had emerged independently.[11][12] In 2019 video producer Thomas Wohlmut released a documentary, ", The Light Between Two Towers, exploring the similarities[13] and adding that the tower may also have played a role in determining the inner structure of the Statue of Liberty.[14]

San Jose Electric-Light War

[edit]In April 1882 Owen sold the tower to Roe's company, by then the San Jose Brush Electric Light Company, to pay remaining construction costs. Brush Electric was bought by the San Jose Light and Power Company in 1889.[15] San Jose Light and Power constructed a new generating facility and supplemented the tower with a dozen 150-foot masts topped with additional arc lights. However, a rival company, the Electric Lighting Company, was awarded the city street lighting franchise in 1890.[15][16] In what was later called the "San Jose Electric-Light War", Roe's company refused to allow them to light the tower, and it was unlighted until the Electric Lighting Company obtained permission from the City Council to overrule San Jose Light and Power's objections since the tower was on public land and had been paid for in large part by public subscription. They rewired it for incandescent light and it was again illuminated on February 28, 1891. San Jose Light and Power retaliated with an injunction; when this could not be served, the manager and a work crew from San Jose Light and Power cut the wiring and removed the new lamps, then guarded the tower against the Electric Lighting Company's men. This occurred on a Sunday, when it was then illegal under California law to serve an injunction, so just before midnight the manager and vice president of the Electric Lighting Company went to the tower and rewired it themselves, in stormy weather.[17] When they were taken to court on a charge of contempt, the judge voided the injunction and fined both companies $50.[18] The legal struggle continued for several years, during which time the tower had a further six arc lamps added, plus small lights on the beams.

In February 1900, San Jose Light and Power declared their intention to sell the tower back to the city, which by that time had not been lit for a year following the dispute with Electric Improvement. However, Electric Improvement's plant had burned down, leaving the city unlit, and the City Council awarded the contract to light the city back to Light and Power.[19] In May, the newly-relit tower reportedly attracted a swarm of beetles, which were pursued by insectivorous birds; some birds and beetles were electrocuted, causing stray cats to mob the base of the tower.[20]

1915 collapse

[edit]The plumbing piping of which the tower was constructed crystallized, masked by the paint,[21] and the joints rusted.[4][22] A wind storm on February 8, 1915, badly damaged it. A Tower Committee raised $6,100 to repair it, and a platform had been built under it and it was to have additional bracing added,[23] but before work could begin, on December 3, 56 mph (90 km/h) winds destroyed it.[24][25] There were no injuries.[26] The city is believed to have paid $4,000 to haul the debris away.

Half-size replica

[edit]A replica approximately half the size of the original, 115 feet in height, was erected at History Park in Kelley Park in 1977, to celebrate the bicentennial of the city. It cost $65,000, paid for by the San Jose Real Estate Board in addition to public subscriptions, and is lighted with 620 clear sign lamps on the tower supports and braces, and topped with a beacon made up of four 400-watt metal-halide lamps.[27]

Modern landmark

[edit]In 2017 Wohlmut and two other members of the San Jose Rotary Club announced plans to raise money to construct a more robust version of the electric light tower with modern lighting and possibly an observation deck, to be located at Plaza de César Chávez.[7][13] By 2018, plans had changed and the San Jose Light Tower Project had dropped the idea of reconstructing the Owen Light Tower, choosing instead to focus on a landmark structure at Guadalupe River Park at a maximum height of 115 to 220 feet (35 to 67 m), depending on its final location.[28]

In March 2019 the San Jose Light Tower Corporation announced plans for a competition to determine the nature of this landmark.[29] By the time entries were closed in July 2020, more than 960 submissions had been made.[30] A group of 34 local community leaders recommended 47 of the entries for further consideration by the jury after deliberating for two days (July 17 and 18); the jury of 14, in turn, selected three finalists after reviewing all 963 entries over three days (August 3, 4, and 8).[31] The three finalists were announced in September 2020:[32]

- Welcome to Wonderland (#179, Rish Saito),[33][34] a walk-through installation 700 feet (210 m) long and 200 feet (61 m) high, consisting of gigantic artificial plants illuminated at night

- Nebula Tower (#797, Quinrong Liu and Ruize Li),[35][36] a framework cube 180 feet (55 m) tall, with a negative space paying homage to the original San Jose Light Tower

- Breeze of Innovation (#914, Fer Jerez and Belen Perez de Juan),[37][38] a forest of 500 white rods 200 feet (61 m) high moving with the wind, again with a negative space the same size as the original Tower. The swaying rods will generate electricity for the building.

Each of the three finalists received a $150,000 stipend to develop their concepts.[32] The design that was selected was Breeze of Innovation, announced on March 25, 2021.[39] Two stairs and one elevator allow visitors entry into the structure, and a continuous ramped path 1,900 feet (580 m) long is provided, terminating at a viewing platform.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ Larson, p. 2; according to Arbuckle, $4,000.

- ^ San Jose Mercury, December 25, 1881, cited in Ernest Freeberg, the Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America, Penguin history of American life, New York: Penguin, 2013, ISBN 978-0-14-312444-3, pp. 50–51.

- ^ "140 years ago, the lights were turned on in San Francisco for the first time". 4 July 2016.

- ^ a b Mary Gottschalk, "It’s the 130th anniversary of San Jose’s once-famous electric tower", The Mercury News, December 8, 2011.

- ^ a b "Livermore ...", Livermore Herald, December 15, 1881, p. 2.

- ^ a b "Electric-light tower at San Jose, California" Harper's Weekly, December 10, 1881.

- ^ a b Pulcrano, Dan (August 2, 2017). "Towering Ambitions". Metro Silicon Valley. pp. 10+.

- ^ According to Arbuckle, p. 497, in Morgan Hill; according to Larson, p. 14, in Los Gatos.

- ^ "The Electric Light in San Jose", Sacramento Daily Union, December 15, 1881.

- ^ "Owen's Electric Tower", The Daily Press (Santa Barbara, California), December 16, 1881, p. 2.

- ^ Eric Carlson, "San Jose Electric Light Tower: San Jose vs. Paris", Soft Underbelly of San Jose, retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Richard von Busack, "A Tall Tale", Metro Silicon Valley, February 20, 2019, p. 28, refers to this as a mock trial held at Santa Clara University.

- ^ a b Sal Pizarro, "New San Jose light tower project gaining support", Mercury News, August 12, 2017.

- ^ Richard von Busack, "A Tall Tale", Metro Silicon Valley, February 20, 2019, p. 28.

- ^ a b "San Jose Electric Tower", San Francisco Call, March 15, 1892, p. 2.

- ^ According to Charles M. Coleman, P. G. and E. of California: The Centennial Story of Pacific Gas and Electric Company 1852–1952, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1952, OCLC 316031512, p. 74, the San Jose Electric Improvement Company; formed by Harry J. Edwards, former general manager of the San Jose Light and Power Company, who left the company shortly after the Brush Electric Light Company merged with the San Jose Gas Company.

- ^ "San Jose's Electric-Light War", San Francisco Call, March 4, 1891, p. 8.

- ^ Coleman, pp. 74–75 adds that the secretary of San Jose Light and Power was also arrested for brandishing a revolver at an Electric Lighting Company work crew.

- ^ "Will save electric tower", San Francisco Call, February 13, 1900, p. 2.

- ^ "Swarms of birds and beetles at San Jose", San Francisco Call, May 6, 1900, p. 17.

- ^ Larson, p. 4.

- ^ Arbuckle, p. 511.

- ^ "Failure of 200-Ft. Electric Light Tower at San Jose, California", Western Machinery and Steel World Volume 7 (1916) pp. 13–14.

- ^ "San Jose Electric Tower falls into street during gale", The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), December 4, 1915, p. 1.

- ^ "Tall tower of San Jose is toppled", The Morning Press (Santa Barbara), December 4, 1915, p. 4.

- ^ According to Gottschalk, Donald O. DeMers Jr. and Ann M. Whitesell, Santa Clara Valley: Images of the Past, San Jose: San Jose Historical Museum Association, 1977, OCLC 3551397, state that one person complained of a hand injury from flying debris.

- ^ Larson, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Pizarro, Sal (December 10, 2018). "San Jose Light Tower project finding a new direction". Mercury News. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Streitfeld, David (March 9, 2019). "In Silicon Valley, Plans for a Monument to Silicon Valley". The New York Times.

- ^ Lorence, Stella (July 28, 2020). "A first look: Silicon Valley landmark designs revealed". San Jose Spotlight. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "All Submissions". Urban Confluence Silicon Valley. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b Pizarro, Sal (September 19, 2020). "San Jose landmark project down to these three choices". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Saito, Rish. "0179 - Welcome to Wonderland". Urban Confluence Silicon Valley. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Welcome to Wonderland Recap on YouTube

- ^ Liu, Quinrong; Li, Ruize. "0797 - The Nebula Tower". Urban Confluence Silicon Valley. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Nebula Tower Recap on YouTube

- ^ Jerez, Fer; Perez de Juan, Belen. "0914 - Breeze of Innovation". Urban Confluence Silicon Valley. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Breeze of Innovation Recap on YouTube

- ^ Wipf, Carly (March 25, 2021). "Winner revealed: A look at San Jose's new iconic landmark". San Jose Spotlight. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Breeze of Innovation: Code Compliance Narrative & Project White Papers (PDF) (Report). Urban Confluence Silicon Valley. January 18, 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Edward F. Caldwell. "San Jose District: San Jose's historic light tower destroyed". Pacific Service Magazine, Pacific Gas and Electric Company. Volume 7 (1915) 339–40.

- Arbuckle, Clyde (1986). "Utilities". Clyde Arbuckle's History of San José. San Jose, California: Memorabilia of San José. pp. 497–98. OCLC 32063141.

- Linda S. Larson. "San Jose's Monument to Progress: The Electric Light Tower". San Jose, California: San Jose Historical Museum Association, 1989. OCLC 20691190

External links

[edit] Media related to San Jose electric light tower at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to San Jose electric light tower at Wikimedia Commons- Electric Light Tower at History San José

- Collapsed Electric Light Tower photographed by John C. Gordon c.1915

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch