Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

Bhagwa Dhwaj or saffron flag, an official symbol of RSS | |

RSS members marching in Bhopal | |

| Abbreviation | RSS |

|---|---|

| Formation | 27 September 1925 |

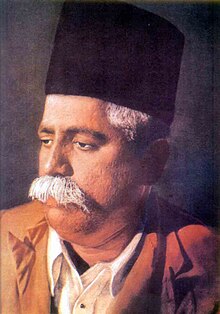

| Founder | K. B. Hedgewar |

| Type | Non-profit political organisation |

| Legal status | Active |

| Purpose | Promotion of Hindu nationalism and Hindutva[1][2] |

| Headquarters | Dr. Hedgewar Bhawan, Sangh Building Road, Nagpur, Maharashtra – 440 032, India |

| Coordinates | 21°08′46″N 79°06′40″E / 21.146°N 79.111°E |

Area served | India |

Membership | |

Sarsanghchalak (Chief) | Mohan Bhagwat |

Sarkaryawah (General Secretary) | Dattatreya Hosabale |

| Affiliations | Sangh Parivar |

| Website | www |

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, Rāṣṭrīya Svayaṃsevak Saṅgh, Hindi pronunciation: [raːʂˈʈriːj(ə) swəjəmˈseːʋək səŋɡʱ], lit. 'National Volunteer Organisation')[7] is an Indian right-wing,[8][9] Hindu nationalist[10][11] volunteer[12] paramilitary organisation.[13] It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar (Hindi for "Sangh family"), which has developed a presence in all facets of Indian society and includes the Bharatiya Janata Party, the ruling political party under Narendra Modi, the 14th prime minister of India.[8] Mohan Bhagwat has served as the Sarsanghchalak of the RSS since March 2009[update].[14]

Founded on 27 September 1925,[15] the initial impetus of the organisation was to provide character training and instil "Hindu discipline" in order to unite the Hindu community and establish a Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation).[16][17] The organisation aims to spread the ideology of Hindutva to "strengthen" the Hindu community and promotes an ideal of upholding an Indian culture and its civilizational values.[2][18] On the other hand, the RSS has been described as "founded on the premise of Hindu supremacy",[19] and has been accused of an intolerance of minorities, in particular anti-Muslim activities.[20]

During the colonial period, the RSS collaborated with the British Raj and played no role in the Indian independence movement.[21][22] After independence, it grew into an influential Hindu nationalist umbrella organisation, spawning several affiliated organisations that established numerous schools, charities, and clubs to spread its ideological beliefs.[17] It was banned in 1947 for four days,[17] and then thrice by the post-independence Indian government, first in 1948 when Nathuram Godse,[23] an erstwhile member of RSS,[24] assassinated Mahatma Gandhi;[17][25][26] then during the Emergency (1975–1977); and for a third time after the demolition of Babri Masjid in 1992. In the 21st century, it is the world's largest far-right organisation by membership.[9] The RSS has been criticised as an extremist organisation and there is a scholarly consensus that it spreads hatred and promotes violence.

Founding

RSS was founded in 1925 by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, a doctor in the city of Nagpur, British India.[27]

Hedgewar was a political protege of B. S. Moonje, a Tilakite Congressman, Hindu Mahasabha politician and social activist from Nagpur. Moonje had sent Hedgewar to Calcutta to pursue his medical studies and to learn combat techniques from the secret revolutionary societies of the Bengalis. Hedgewar became a member of the Anushilan Samiti, an anti-British revolutionary group, getting into its inner circle. The secretive methods of these societies were eventually used by him in organising the RSS.[28][29][30]

After returning to Nagpur, Hedgewar organised anti-British activities through the Kranti Dal (Party of Revolution) and participated in independence activist Tilak's Home Rule campaign in 1918. According to the official RSS history,[31] he came to realise that revolutionary activities alone were not enough to overthrow the British. After reading V. D. Savarkar's Hindutva, published in Nagpur in 1923, and meeting Savarkar in the Ratnagiri prison in 1925, Hedgewar was extremely influenced by him, and he founded the RSS with the objective of strengthening Hindu society.[28][29][30][32]

Hedgewar believed that a handful of British were able to rule over the vast country of India because Hindus were disunited, lacked valour (pararkram) and lacked a civic character. He recruited energetic Hindu youth with revolutionary fervour, gave them a uniform of a black forage cap, khaki shirt (later white shirt) and khaki shorts—emulating the uniform of the Indian Imperial Police—and taught them paramilitary techniques with lathi (bamboo staff), sword, javelin, and dagger. Hindu ceremonies and rituals played a large role in the organisation, not so much for religious observance, but to provide awareness of India's glorious past and to bind the members in a religious communion. Hedgewar also held weekly sessions of what he called baudhik (ideological education), consisting of simple questions to the novices concerning the Hindu nation and its history and heroes, especially warrior king Shivaji. The saffron flag of Shivaji, the Bhagwa Dhwaj, was used as the emblem for the new organisation. Its public tasks involved protecting Hindu pilgrims at festivals and confronting Muslim resistance against Hindu processions near mosques.[28][29][30]

Two years into the life of the organisation, in 1927, Hedgewar organised an "Officers' Training Camp" with the objective of forming a corps of key workers, whom he called pracharaks (full-time functionaries or "propagators"). He asked the volunteers to first become "sadhus" (ascetics), renouncing professional and family lives and dedicating their lives to the cause of the RSS. Hedgewar is believed to have embraced the doctrine of renunciation after it had been reinterpreted by nationalists such as Aurobindo. The tradition of renunciation gave the RSS the character of a 'Hindu sect'.[33] Developing a network of shakhas (branches) was the main preoccupation for Hedgewar throughout his career as the RSS chief. The first pracharaks were responsible for establishing as many shakhas as possible, first in Nagpur, then across Maharashtra, and eventually in the rest of India. P. B. Dani was sent to establish a shakha at the Benaras Hindu University; other universities were similarly targeted to recruit new followers among the student population. Three pracharaks went to Punjab: Appaji Joshi to Sialkot, Moreshwar Munje to the DAV College in Rawalpindi and Raja Bhau Paturkar to the DAV College in Lahore. In 1940, Madhavrao Muley was appointed as the prant pracharak (regional head) for Punjab in Lahore.[34]

Motivations

Scholars differ on Hedgewar's motivations for forming the RSS, especially because he never involved the RSS in the independence movement against the British rule. French political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot says that the RSS was intended to propagate the ideology of Hindutva and to provide "new physical strength" to the majority community.[2][35]

After Tilak's demise in 1920, like other followers of Tilak in Nagpur, Hedgewar was opposed to some of the programmes adopted by Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi's stance on the Indian Muslim Khilafat issue was a cause for concern to Hedgewar, and so was that the 'cow protection' was not on the Congress agenda. This led Hedgewar, along with other Tilakities, to part ways with Gandhi. In 1921, Hedgewar was arrested on the charges of 'sedition' over his speeches at Katol and Bharatwada. Ultimately, he was sentenced to 1 year in prison.[36]

He was released in July 1922. Hedgewar was distressed at the lack of organisation among volunteer organisations of Congress. Subsequently, he felt the need to create an independent organisation that was based on the country's traditions and history. He held meetings with prominent political figures in Nagpur between 1922–1924. He visited Gandhi's ashram in nearby Wardha in 1924 and discussed a number of things. After this meeting, he left Wardha to plan to unite the often antagonistic Hindu groups into a common nationalist movement.[36][37]

Hindu–Muslim relations

The 1920s witnessed a significant deterioration in the relations between Hindus and Muslims. The Muslim masses were mobilised by the Khilafat movement, opposing dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire by the Allies and some demanded the reinstatement of the Caliphate in Turkey.[38] Mahatma Gandhi made an alliance with the movement for conducting his own Non-co-operation movement. Gandhi aimed to create Hindu–Muslim unity in forming the alliance. However, the alliance saw a "common enemy", not a "common enmity".[39] When the government refused to entertain demands of Khilafatists, this would cause some Muslims to turn their anger towards Hindus.[40] The first major incident of religious violence was reportedly the Moplah rebellion in August 1921, it was widely narrated that the rebellion ended in large-scale violence against Hindu officials in Malabar. A cycle of inter-communal violence throughout India followed for several years.[41] In 1923, there were riots in Nagpur, called "Muslim riots" by Hedgewar, where Hindus were felt to be "totally disorganized and panicky." These incidents made a major impression on Hedgewar and convinced him of the need to organise the Hindu society.[32][42]

After acquiring about 100 swayamsevaks (volunteers) to the RSS in 1927, Hedgewar took the issue to the Muslim domain. He led the Hindu religious procession for Ganesha, beating the drums in defiance of the usual practice not to pass in front of a mosque with music.[43] On the day of Lakshmi Puja on 4 September, Muslims are said to have retaliated. When the Hindu procession reached a mosque in the Mahal area of Nagpur, Muslims blocked it. Later in the afternoon, they attacked the Hindu residences in the Mahal area. It is said that the RSS cadres were prepared for the attack and beat the Muslim rioters back. Riots continued for 3 days and the army had to be called in to quell the violence. RSS organised the Hindu resistance and protected the Hindu households while the Muslim households had to leave Nagpur en masse for safety.[44][45][32][46] Tapan Basu et al. note the accounts of "Muslim aggressiveness" and the "Hindu self-defence" in the RSS descriptions of the incident. The above incident vastly enhanced the prestige of the RSS and enabled its subsequent expansion.[45]

Stigmatisation and emulation

Christophe Jaffrelot points out the theme of "stigmatisation and emulation" in the ideology of the RSS along with other Hindu nationalist movements such as the Arya Samaj and the Hindu Mahasabha. Muslims, Christians and the British were thought of as "foreign bodies" implanted in the Hindu nation, who were able to exploit the disunity and absence of valour among the Hindus in order to subdue them. The solution lay in emulating the characteristics of these "Threatening Others" that were perceived to give them strength, such as paramilitary organisation, emphasis on unity and nationalism. The Hindu nationalists combined these emulatory aspects with a selective borrowing of traditions from the Hindu past to achieve a synthesis that was uniquely Indian and Hindu.[47]

Hindu Mahasabha influence

The Hindu Mahasabha, which was initially a special interest group within the Indian National Congress and later an independent party, was an important influence on the RSS, even though it is rarely acknowledged.[citation needed] In 1923, prominent Hindu leaders like Madan Mohan Malaviya met together on this platform and voiced their concerns on the 'division in the Hindu community'. In his presidential speech to Mahasabha, Malaviya stated: "Friendship could exist between equals. If the Hindus made themselves strong and the rowdy section among the Mahomedans were convinced they could not safely rob and dishonour Hindus, unity would be established on a stable basis." He wanted the activists 'to educate all boys and girls, establish akharas (gymnasiums), establish a volunteer corps to persuade people to comply with decisions of the Hindu Mahasabha, to accept untouchables as Hindus and grant them the right to use wells, enter temples, get an education.' Later, Hindu Mahasabha leader V. D. Savarkar's 'Hindutva' ideology also had a profound impact on Hedgewar's thinking about the 'Hindu nation'.[36]

The initial meeting for the formation of the Sangh on the Vijaya Dashami day of 1925 was held between Hedgewar and four Hindu Mahasabha leaders: B. S. Moonje, Ganesh Savarkar, L. V. Paranjpe and B. B. Tholkar. RSS took part as a volunteer force in organising the Hindu Mahasabha annual meeting in Akola in 1931. Moonje remained a patron of the RSS throughout his life. Both he and Ganesh Savarkar worked to spread the RSS shakhas in Maharashtra, Panjab, Delhi, and the princely states by initiating contacts with local leaders. Savarkar merged his own youth organisation Tarun Hindu Sabha with the RSS and helped its expansion. V. D. Savarkar, after his release in 1937, joined them in spreading the RSS and giving speeches in its support. Officials in the Home Department called the RSS the "volunteer organisation of the Hindu Mahasabha."[48][49]

History

Indian Independence movement

Since its formation the RSS opposed joining the independence movement against British rule in India.[22] Portraying itself as a social movement, Hedgewar also kept the organisation from having any direct affiliation with political organisations then fighting British rule.[50] RSS rejected Gandhi's willingness to co-operate with the Muslims.[51][52]

In accordance with Hedgewar's tradition of keeping the RSS away from the Indian Independence movement, any political activity that could be construed as being anti-British was carefully avoided. According to the RSS biographer C. P. Bhishikar, Hedgewar talked only about Hindu organisations and avoided any direct comment on the Government.[53] The "Independence Day" announced by the Indian National Congress for 26 January 1930 was celebrated by the RSS that year but was subsequently avoided. The Tricolor of the Indian national movement was shunned.[54][55][56][57] Hedgewar personally participated in the 'Satyagraha' launched by Gandhi in April 1930, but he did not get the RSS involved in the movement. He sent information everywhere that the RSS would not participate in the Satyagraha. However, those wishing to participate individually were not prohibited.[58][59] In 1934, Congress passed a resolution prohibiting its members from joining the RSS, Hindu Mahasabha, or the Muslim League.[54]

M. S. Golwalkar, who became the leader of the RSS in 1940, continued and further strengthened the isolation from the independence movement. In his view, the RSS had pledged to achieve freedom through "defending religion and culture", not by fighting the British.[60][61][62] Golwalkar lamented the anti-British nationalism, calling it a "reactionary view" that, he claimed, had disastrous effects upon the entire course of the freedom struggle.[63][64] It is believed that Golwalkar did not want to give the British an excuse to ban the RSS. He complied with all the strictures imposed by the Government during the Second World War, even announcing the termination of the RSS military department.[65][66] The British Government believed that the RSS was not supporting any civil disobedience against them, and their other political activities could thus be overlooked. The British Home Department took note of the fact that the speakers at the RSS meetings urged the members to keep aloof from the anti-British movements of the Indian National Congress, which was duly followed.[67] The Home Department did not see the RSS as a problem for law and order in British India.[65][66] The Bombay government appreciated the RSS by noting that the Sangh had scrupulously kept itself within the law and refrained from taking part in the disturbances (Quit India Movement) that broke out in August 1942.[68][69][70] It also reported that the RSS had not, in any way, infringed upon government orders and had always shown a willingness to comply with the law. The Bombay Government report further noted that in December 1940, orders had been issued to the provincial RSS leaders to desist from any activities that the British Government considered objectionable, and the RSS, in turn, had assured the British authorities that "it had no intentions of offending against the orders of the Government".[71][72]

Golwalkar later openly admitted the fact that the RSS did not participate in the Quit India Movement. He agreed that such a stance led to a perception of the RSS as an inactive organisation, whose statements had no substance in reality.[60][73] Similarly, RSS neither supported nor joined in the Royal Indian Navy mutiny against the British in 1946.[52]

Overall, the RSS opposed joining the independence movement, instead adopting a policy of collaboration with the British regime.[21][22]

Partition

The Partition of India affected millions of Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims attempting to escape the violence and carnage that followed.[74] During the partition, the RSS helped the Hindu refugees fleeing West Punjab; its activists also played an active role in the communal violence during Hindu-Muslim riots in North India, though this was officially not sanctioned by the leadership. To the RSS activists, the partition was a result of mistaken soft-line towards the Muslims, which only confirmed the natural moral weaknesses and corruptibility of the politicians. The RSS blamed Gandhi, Nehru and Patel for their 'naivety which resulted in the partition' and held them responsible for the mass killings and displacement of the millions of people.[75][76][77]

First ban

The first ban on the RSS was imposed in Punjab Province (British India) on 24 January 1947 by Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana, the premier of the ruling Unionist Party, a party that represented the interests of the landed gentry and landlords of Punjab, which included Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs. Along with the RSS, the Muslim National Guard was also banned.[78][79] The ban was lifted on 28 January 1947.[78]

Opposition to the National Flag of India

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh initially did not recognise the Tricolor as the National Flag of India. The RSS-inspired publication, the Organiser,[80] demanded, in an editorial titled "National Flag", that the Bhagwa Dhwaj be adopted as the National Flag of India.[81] After the Tricolor was adopted as the National Flag by the Constituent Assembly of India on 22 July 1947, the Organiser viciously attacked the Tricolor and the Constituent Assembly's decision. In an article titled "Mystery behind the Bhagwa Dhwaj", the Organiser stated:[82][83]

The people who have come to power by the kick of fate may give in our hands the Tricolor but it [will] never be respected and owned by Hindus. The word three is in itself an evil, and a flag having three colours will certainly produce a very bad psychological effect and is injurious to a country.

In an essay titled "Drifting and Drafting" published in Bunch of Thoughts, Golwalkar lamented the choice of the Tricolor as the National Flag and compared it to an intellectual vacuum/void. In his words:[84][85][86][87]

Our leaders have set up a new flag for the country. Why did they do so? It just is a case of drifting and imitating ... Ours is an ancient and great nation with a glorious past. Then, had we no flag of our own? Had we no national emblem at all these thousands of years? Undoubtedly we had. Then why this utter void, this utter vacuum in our minds.

The RSS hoisted the National Flag of India at its Nagpur headquarters only twice, on 14 August 1947 and on 26 January 1950, but stopped doing so after that.[88] This issue has always been a source of controversy. In 2001 three activists of Rashtrapremi Yuwa Dal – president Baba Mendhe, and members Ramesh Kalambe and Dilip Chattani, along with others – allegedly entered the RSS headquarters in Reshimbagh, Nagpur, on 26 January, the Republic Day of India, and forcibly hoisted the national flag there amid patriotic slogans. They contended that the RSS had never before or after independence, ever hoisted the Tricolor in their premises. Offences were registered by the Bombay Police against the trio, who were then jailed. They were discharged by the court after eleven years in 2013.[89][90] The arrests and the flag-hoisting issue stoked a controversy, which was raised in the Parliament as well. Hoisting of the flag was very restrictive until the formation of the flag code of India (2002).[91][92][93] Subsequently, in 2002, the National Flag was raised in the RSS headquarters on Republic Day for the first time in 52 years.[88]

Opposition to the Constitution of India

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh initially did not recognise the Constitution of India, strongly criticising it because the Indian Constitution made no mention of "Manu's laws" – from the ancient Hindu text Manusmriti.[56] When the Constituent Assembly finalised the constitution, the RSS mouthpiece, the Organiser, complained in an editorial dated 30 November 1949:[56]

But in our constitution, there is no mention of that unique constitutional development in ancient Bharat... To this day his laws as enunciated in the Manusmriti excite the admiration of the world and elicit spontaneous obedience and conformity. But to our constitutional pundits that means nothing."

On 6 February 1950 the Organiser carried another article, titled "Manu Rules our Hearts", written by a retired High Court Judge named Sankar Subba Aiyar, that reaffirmed their support for the Manusmriti as the final lawgiving authority for Hindus, rather than the Constitution of India. It stated:[94]

Even though Dr. Ambedkar is reported to have recently stated in Bombay that the days of Manu have ended it is nevertheless a fact that the daily lives of Hindus are even at present-day affected by the principles and injunctions contained in the Manusmrithi and other Smritis. Even an unorthodox Hindu feels himself bound at least in some matters by the rules contained in the Smrithis and he feels powerless to give up altogether his adherence to them.

The RSS' opposition to, and vitriolic attacks against, the Constitution of India continued post-independence. In 1966 Golwalkar, in his book titled Bunch of Thoughts asserted:[56][85]

Our Constitution too is just a cumbersome and heterogeneous piecing together of various articles from various Constitutions of Western countries. It has absolutely nothing, which can be called our own. Is there a single word of reference in its guiding principles as to what our national mission is and what our keynote in life is? No!

Second ban

India's first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had been vigilant towards RSS since he had taken charge. When Golwalkar wrote to Nehru asking for the lifting of the ban on RSS after Gandhi's assassination, Nehru replied that the government had proof that RSS activities were 'anti-national' by virtue of being 'communalist'. In his letter to the heads of provincial governments in December 1947, Nehru wrote that "we have a great deal of evidence to show that RSS is an organisation which is in the nature of a private army and which is definitely proceeding on the strictest Nazi lines, even following the techniques of the organisation".[95]

In January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by a member of the RSS, Nathuram Godse.[96][24] Following the assassination, many prominent leaders of the RSS were arrested, and the RSS as an organisation was banned on 4 February 1948. During the court proceedings in relation to the assassination Godse began claiming that he had left the organisation in 1946.[26] A Commission of Inquiry into Conspiracy to the murder of Gandhi was set, and its report was published by India's Ministry of Home Affairs in the year 1970. Accordingly, the Justice Kapur Commission[97] noted that the "RSS as such were not responsible for the murder of Mahatma Gandhi, meaning thereby that one could not name the organisation as such as being responsible for that most diabolical crime, the murder of the apostle of peace. It has not been proved that they (the accused) were members of the RSS."[97]: 165 However, the then Indian Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel had remarked that the "RSS men expressed joy and distributed sweets after Gandhi's death".[98] The association with the incident also made the RSS "very unpopular and considerably dented its polarizing appeal".[99]

RSS leaders were acquitted of the conspiracy charge by the Supreme Court of India. Following his release in August 1948, Golwalkar wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to lift the ban on RSS. After Nehru replied that the matter was the responsibility of the Home Minister, Golwalkar consulted Vallabhai Patel regarding the same. Patel then demanded an absolute pre-condition that the RSS adopt a formal written constitution[100] and make it public, where Patel expected RSS to pledge its loyalty to the Constitution of India, accept the Tricolor as the National Flag of India, define the power of the head of the organisation, make the organisation democratic by holding internal elections, authorisation of their parents before enrolling the pre-adolescents into the movement, and to renounce violence and secrecy.[101][102][103]: 42– Golwalkar launched a huge agitation against this demand during which he was imprisoned again. Later, a constitution was drafted for RSS, which, however, initially did not meet any of Patel's demands. After a failed attempt to agitate again, eventually the RSS's constitution was amended according to Patel's wishes with the exception of the procedure for selecting the head of the organisation and the enrolment of pre-adolescents. However, the organisation's internal democracy, which was written into its constitution, remained a 'dead letter'.[104]

Sardar Vallabhai Patel, the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of India, said in early January 1948 that the RSS activists were "patriots who love their country". He asked the Congressmen to 'win over' the RSS by love, instead of trying to 'crush' them. He also appealed to the RSS to join the Congress instead of opposing it. Jaffrelot says that this attitude of Patel can be partly explained by the assistance the RSS gave the Indian administration in maintaining public order in September 1947, and that his expression of 'qualified sympathy' towards RSS reflected the long-standing inclination of several Hindu traditionalists in Congress. However, after Gandhi's assassination on 30 January 1948, Patel began to view that the activities of RSS were a danger to public security.[105][106] In his reply letter to Golwalkar on 11 September 1948 regarding the lifting of ban on RSS, Patel stated that though RSS did service to the Hindu society by helping and protecting the Hindus when in need during partition violence, they also began attacking Muslims with revenge and went against "innocent men, women and children". He said that the speeches of RSS were "full of communal poison", and as a result of that 'poison', he remarked, India had to lose Gandhi, noting that the RSS men had celebrated Gandhi's death. Patel was also apprehensive of the secrecy in the working manner of RSS and complained that all of its provincial heads were Maratha Brahmins. He criticised the RSS for having its own army inside India, which he said, cannot be permitted as "it was a potential danger to the State". He also remarked: "The members of RSS claimed to be the defenders of Hinduism. But they must understand that Hinduism would not be saved by rowdyism."[98]

On 11 July 1949 the Government of India lifted the ban on the RSS by issuing a communique stating that the decision to lift the ban on the RSS had been taken in view of the RSS leader Golwalkar's undertaking to make the group's loyalty towards the Constitution of India and acceptance and respect towards the National Flag of India more explicit in the Constitution of the RSS, which was to be worked out in a democratic manner.[27][103]

Decolonisation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli

After India had achieved independence, the RSS was one of the socio-political organisations that supported and participated in movements to decolonise Dadra and Nagar Haveli, which at that time was ruled by Portugal. In early 1954 volunteers Raja Wakankar and Nana Kajrekar of the RSS visited the area round about Dadra, Nagar Haveli, and Daman several times to study the topography and get acquainted with locals who wanted the area to change from being a Portuguese colony to being an Indian union territory. In April 1954 the RSS formed a coalition with the National Movement Liberation Organisation (NMLO) and the Azad Gomantak Dal (AGD) for the annexation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli into the Republic of India.[107] On the night of 21 July, United Front of Goans, a group working independently of the coalition, captured the Portuguese police station at Dadra and declared Dadra independent. Subsequently, on 28 July, volunteer teams from the RSS and AGD captured the territories of Naroli and Phiparia and ultimately the capital of Silvassa. The Portuguese forces that had escaped and moved towards Nagar Haveli, were assaulted at Khandvel and forced to retreat until they surrendered to the Indian border police at Udava on 11 August 1954. A native administration was set up with Appasaheb Karmalkar of the NMLO as the Administrator of Dadra and Nagar Haveli on 11 August 1954.[107]

The capture of Dadra and Nagar Haveli gave a boost to the movement against Portuguese colonial rule in the Indian subcontinent.[107] In 1955, RSS leaders demanded the end of Portuguese rule in Goa and its integration into India. When Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru refused to provide an armed intervention, RSS leader Jagannath Rao Joshi led the Satyagraha agitation straight into Goa. He was imprisoned with his followers by the Portuguese police. The nonviolent protests continued but met with repression. On 15 August 1955, the Portuguese police opened fire on the satyagrahis, killing thirty or so civilians.[108]

The Emergency

In 1975 the Indira Gandhi government proclaimed emergency rule in India, thereby curtailing the freedom of the press.[109] The Emergency was imposed after Jayaprakash Narayan urged people to start civil disobedience. Narayan also asked the army and the police to disobey the government.[110][111] A number of opposition leaders including Narayan were arrested.[112] The RSS, which was seen as being close to opposition leaders, and with its large organisational base, was seen to have the capability of organising protests against the government, and was thus also banned.[113]

Deoras, the then chief of the RSS, wrote letters to Indira Gandhi, promising her to extend the organisation's co-operation in return for the lifting of the ban, asserting that RSS had no connection with the movement in Bihar and that in Gujarat. He tried to persuade Vinoba Bhave to mediate between the RSS and the government and also sought the offices of Sanjay Gandhi, Indira Gandhi's son.[114][115] Provincial RSS organiser Lala Hansraj Gupta had also written a letter to Indira Gandhi and promised to begin "a new era of co-operation" between the Sangh Parivar and the Congress in exchange for the removal of the ban on the RSS.[116] A number of volunteers of the RSS have claimed that they carried out activities underground during the Emergency. RSS claimed that the movement was dominated by tens of thousands of RSS cadres.[117][118][116]

The Emergency was lifted in 1977, and with it, the ban on the RSS was also lifted. The Emergency is said to have legitimised the role of RSS in Indian politics, which had not been possible ever since the stain the organisation had acquired following Mahatma Gandhi's assassination in 1948, thereby 'sowing the seeds' for the Hindutva politics of the following decades.[119]

Structure

RSS does not have any formal membership. According to the official website, men and boys can become members by joining the nearest shakha, which is the basic unit. Although the RSS claims not to keep membership records, it is estimated to have had 2.5 to 6.0 million members in 2001.[120]

Leadership and member positions

There are the following terms to describe RSS leaders and members:

- Sarsanghchalak: The Sarsanghchalak is the head of the RSS organisation; the position is decided through nomination by the predecessor.

- Sarkaryavah: equivalent to general secretary, executive head.[121] Elected by the elected members of the Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha.[122] Dattatreya Hosabale is the Sarkaryawah as of 2021[update].[123] Suresh Joshi preceded him; he had held the post for 12 years.[124]

- Sah-Sarkaryavah: Joint general secretary, of which there are four.[121][125] Notable Sah-Sarkarayvahs include Dattatreya Hosabale.[126][127][128][129]

- Vicharak: A number of RSS leaders serve as vicharak or ideologues for the organisation.[130][131][132]

- Pracharak: Active, full-time missionary who spreads RSS doctrine.[121] The system of pracharak or RSS missionaries has been called the life blood of the organisation. A number of these men devote themselves to lifetime of celibacy, poverty, and service to the organisation. The pracharaks were instrumental in spreading the organisation from its roots in Nagpur to the rest of the country.[133] There are about 2500 pracharaks in RSS.[134] The two most well known former pracharaks are former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India since May 2014[update].[135]

- Karyakarta: Active functionary. To become a karyakarta, swayamsevak members undergo four levels of ideological and physical training in Sangh Shiksha Varg camps. 95% of karyakartas are known as grahastha karyakartas, or householders, supporting the organisation part-time; while 5% are pracharaks, who support the organisation full-time.[136]

- Mukhya-Shikshak: The head teacher and chief of a shakha.[121]

- Karyawah: The executive head of a shakha.[121]

- Gatanayak: Group leader.[121]

- Swayamsevak: Volunteer.[137] Svayam[138] can mean "one's self" or "voluntary," and sevaka[139] Atal Bihari Vajpayee described himself as a swayamsevak.[140] They attend the shakhas of the RSS.[136]

Shakhas

The term shakha is Hindi for "branch". Most of the organisational work of the RSS is done through the co-ordination of the various shakhas. These shakhas are run for one hour in public places. The number of shakhas increased from 8500 in 1975 to 11,000 in 1977, and became 20,000 by 1982.[114] In 2004 more than 51,000 shakhas were run throughout India. The number of shakas had fallen by over 10,000 after the fall of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government in 2004. However, by mid-2014, the number had again increased to about 40,000 after the return of BJP to power in the same year.[141][142][143] This number stood at 51,335 in August 2015.[144]

The shakhas conduct various activities for its volunteers such as physical fitness through yoga, exercises, and games, and activities that encourage civic awareness, social service, community living, and patriotism.[145] Volunteers are trained in first aid and in rescue and rehabilitation operations, and are encouraged to become involved in community development.[145][146]

Generally, shakhas involve the gathering of male RSS members to train in martial arts, exercise in other ways, and "recite nationalist stories" to outsiders.[147]

Most of the shakhas are located in the Hindi-speaking regions. As of 2016 Delhi had 1,898 shakhas.[148] There are more than 8,000 shakhas in UP, 6,845 shakhas in Kerala,[149] 4,000 in Maharashtra, and around 1,000 in Gujarat.[150] In northeast India, there are more than 1,000 shakhas, including 903 in Assam, 107 in Manipur, 36 in Arunachal, and 4 in Nagaland.[151][152] In Punjab, there are more than 900 shakhas as of 2016.[153] As of late 2015 there were a total of 1,421 shakhas in Bihar,[154] 4,870 in Rajasthan,[155] 1,252 in Uttarakhand,[156] 2,060 in Tamil Nadu,[157] and 1,492 in West Bengal.[158] There are close to 500 shakhas in Jammu and Kashmir,[159] 130 in Tripura, and 46 in Meghalaya.[160]

As per the RSS Annual Report of 2019, there were a total of 84,877 shakhas, of which 59,266 are being held daily; 17,229 are weekly shakhas (58,967 in 2018, 57,165 in 2017, and 56,569 in 2016)[161][162]

Uniform

In October 2016, the RSS replaced the uniform of khaki shorts its cadre had worn for 91 years with dark brown trousers.[163][164]

Anthem

The song Namastē Sadāvatsale Matrubhoomē is the anthem or prayer of the RSS, saluting the motherland.[165]

Affiliated organisations

Organisations that are inspired by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh's ideology refer to themselves as members of the Sangh Parivar.[120] In most cases, pracharaks (full-time volunteers of the RSS) were deputed to start up and manage these organisations in their initial years.

The affiliated organisations include:[166]

- Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), literally, Indian People's Party (23m)[167]

- Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, literally, Indian Farmers' Association (8m)[167]

- Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, literally, Indian Labour Association (10 million as of 2009)[167]

- Seva Bharti, Organisation for service of the needy.

- Rashtra Sevika Samiti, literally, National Volunteer Association for Women (1.8m)[167]

- Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, literally, All India Students' Forum (2.8m)[167]

- Shiksha Bharati (2.1m)[167]

- Vishwa Hindu Parishad, World Hindu Council (2.8m)[167]

- Bhartiya Baudh Sangh, Indian Buddhist Association[168]

- Bharatiya Yuva Seva Sangh (BYSS), Youth Awakening Front[citation needed]

- Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh, literally, Hindu Volunteer Association – overseas wing

- Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, Nativist Awakening Front[169]

- Saraswati Shishu Mandir, Nursery

- Vidya Bharati, Educational Institutes

- Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram (Ashram for the Tribal Welfare), Organisations for the improvement of tribals; and Friends of Tribals Society

- Muslim Rashtriya Manch (Muslim National Forum), Organisation for the improvement of Muslims

- Bajrang Dal, Army of Hanuman (2m)

- Anusuchit Jati-Jamati Arakshan Bachao Parishad, Organisation for the improvement of Dalits

- Laghu Udyog Bharati, an extensive network of small industries.[170][171]

- Bharatiya Vichara Kendra, Think Tank

- Vishwa Samvad Kendra, Communication Wing, spread all over India for media related work, having a team of IT professionals (samvada.org)

- Rashtriya Sikh Sangat, National Sikh Association, a sociocultural organisation with the aim to spread the knowledge of Gurbani to the Indian society.[172]

- Vivekananda Kendra, promotion of Swami Vivekananda's ideas with Vivekananda International Foundation in New Delhi as a public policy think tank with six centres of study

Although RSS generally endorses the BJP, it has at times refused to do so due to the difference of opinion with the party.[173][174]

Ideology

Mission

Golwalkar described the mission of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh as the revitalisation of the Indian value system based on universalism and peace and prosperity to all.[175] Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, the worldview that the whole world is one family, propounded by the ancient thinkers of India, is considered one of the ideologies of the organisation.[176]

But the immediate focus, the leaders believe, is on the Hindu renaissance, which would build an egalitarian society and a strong India that could propound this philosophy. Hence, the focus is on social reform, economic upliftment of the downtrodden, and the protection of the cultural diversity of the natives in India.[176] The organisation says it aspires to unite all Hindus and build a strong India that can contribute to the welfare of the world. In the words of RSS ideologue and the second head of the RSS, Golwalkar, "in order to be able to contribute our unique knowledge to mankind, in order to be able to live and strive for the unity and welfare of the world, we stand before the world as a self-confident, resurgent and mighty nation".[175]

In Vichardhara (ideology), Golwalkar affirms the RSS mission of integration as:[175]

RSS has been making determined efforts to inculcate in our people the burning devotion for Bharat and its national ethos; kindle in them the spirit of dedication and sterling qualities and character; rouse social consciousness, mutual good-will, love and cooperation among them all; to make them realise that casts, creeds, and languages are secondary and that service to the nation is the supreme end and to mold their behaviour accordingly; instill in them a sense of true humility and discipline and train their bodies to be strong and robust so as to shoulder any social responsibility; and thus to create all-round Anushasana (Discipline) in all walks of life and build together all our people into a unified harmonious national whole, extending from Himalayas to Kanyakumari.

Golwalkar and Balasaheb Deoras, the second and third supreme leaders of the RSS, spoke against the caste system, though they did not support its abolition.[177]

Comparisons with fascism

Jaffrelot observes that although the RSS with its paramilitary style of functioning and its emphasis on discipline has sometimes been seen by some as "an Indian version of fascism",[178] he argues that "RSS's ideology treats society as an organism with a secular spirit, which is implanted not so much in the race as in a socio-cultural system and which will be regenerated over the course of time by patient work at the grassroots". He writes that "ideology of the RSS did not develop a theory of the state and the race, a crucial element in European nationalisms: Nazism and Fascism"[178] and that the RSS leaders were interested in culture as opposed to racial sameness.[179]

The likening of the Sangh Parivar to fascism by Western critics has also been countered by Jyotirmaya Sharma, who labelled it as an attempt by them to "make sense of the growth of extremist politics and intolerance within their society", and that such "simplistic transference" has done great injustice to knowledge of Hindu nationalist politics.[180]

Stance on non-Hindu communities

When it came to non-Hindu religions, the view of Golwalkar (who once supported Hitler's creation of a supreme race by suppression of minorities)[181] on minorities was that of extreme intolerance. In a 1998 magazine article, some RSS and BJP members were said to have distanced themselves from Golwalkar's views, though not entirely:[182]

The non-Hindu people of Hindustan must either adopt Hindu culture and languages, must learn and respect and hold in reverence the Hindu religion, must entertain no idea but of those of glorification of the Hindu race and culture ... in a word they must cease to be foreigners; or may stay in the country, wholly subordinated to the Hindu nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment—not even citizens' rights.

Golwalkar also explains that RSS does not intend to compete in electioneering politics or share power. The movement considers Hindus as inclusive of Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, tribals, untouchables, Veerashaivism, Arya Samaj, Ramakrishna Mission, and other groups as a community, a view similar to the inclusive referencing of the term Hindu in the Indian Constitution Article 25 (2)(b).[184][185][186]

In spite of the organisation's hostile rhetoric against their religions, the RSS also has Muslim and Christian members. According to the party's official documents, Indian Muslims and Christians are still descendants of Hindus that happened to be converted to foreign faiths, so as long as they agree with its beliefs they can also be members. They are still required to attend the shakhas, and recite Hindu hymns, even by breaking Ramadhan fasts when possible.[121][187] The Muslim Rashtriya Manch is considered as a wing of the RSS for Muslim members.[188]

In January 2020, the RSS along with other right-wing political parties and religious organisations such as BJP, Vishwa Hindu Parishad and HJV held protests, which allegedly demanded that the statue of Jesus be not installed at Kapala Hills of Kanakapura. The 10 acres (4.0 ha) of land[189] was originally donated by the government to the Christian community after D. K. Shivakumar, the MLA of Indian National Congress submitted a request to the state government for land donation to the community.[190]

LGBT issues

Historically, the RSS has expressed a negative view of homosexuality,[191] though it has moderated this position in recent years, expressing support for the decriminalisation of homosexuality but opposition to the recognition of same-sex unions in India.[192] In 2016, RSS member Rakesh Sinha claimed that efforts to decriminalise homosexuality in India were the product of a "European mindset".[193] In 2018, the RSS expressed support for Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India, which decriminalised homosexual activity in India, while simultaneously condemning efforts to legalise gay marriage and referring to homosexuality as "unnatural".[194]

Similarly, in a book published in 2019, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat stated that homosexuality should remain a "private matter", while also arguing that "gay marriages should not be institutionalised for it will institutionalise homosexuality".[195] In January 2023, Mohan Bhagwat again stated that LGBT individuals "should have their own private and social space as they are humans and have the right to live as others". However, some critics have alleged these remarks are "insincere".[193][196]

In March 2023, RSS general secretary Dattatreya Hosabale reiterated the organisation's opposition to the legalisation of gay marriage, stating that in Hinduism "marriage is [a] 'Sanskar' [Hindu sacrament]" that necessarily involves two people of opposite gender.[197][198] These comments were made in support of an affidavit the BJP-ruled Government of India filed with the Supreme Court of India which argued against the legalisation of same-sex marriage. When the Supreme Court handed down a verdict against legalisation later that year, the RSS "welcomed" the ruling, and additionally expressed their opposition to giving same-sex couples the right to adopt children.[199]

Attitude towards Jews

Before World War II, the RSS leaders admired Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.[17][200] Golwalkar took inspiration from Adolf Hitler's ideology of racial purity.[201] However, the RSS's stance changed during the war; the organisation firmly supported the British war effort against Hitler and the Axis Powers.[68] The RSS leaders were supportive of the formation of Jewish State of Israel.[202] Golwalkar admired the Jews for maintaining their "religion, culture and language".[203]

Social service and reform

Participation in land reforms

The RSS volunteers participated in the Bhoodan movement organised by Gandhian leader Vinobha Bhave, who had met RSS leader Golwalkar in Meerut in November 1951. Golwalkar had been inspired by the movement that encouraged land reform through voluntary means. He pledged the support of the RSS for this movement.[204] Consequently, many RSS volunteers, led by Nanaji Deshmukh, participated in the movement.[12] But Golwalkar was also critical of the Bhoodan movement on other occasions for being reactionary and for working "merely with a view to counteracting Communism". He believed that the movement should inculcate a faith in the masses that would make them rise above the base appeal of Communism.[175]

Reform in 'caste'

The RSS has advocated the training of Dalits and other backward classes as temple high priests (a position traditionally reserved for Caste Brahmins and denied to lower castes). They argue that the social divisiveness of the caste system is responsible for the lack of adherence to Hindu values and traditions, and that reaching out to the lower castes in this manner will be a remedy to the problem.[205] The RSS has also condemned upper-caste Hindus for preventing Dalits from worshipping at temples, saying that "even God will desert the temple in which Dalits cannot enter".[206]

Jaffrelot says that "there is insufficient data available to carry out a statistical analysis of social origins of the early RSS leaders" but goes on to conclude that, based on some known profiles, most of the RSS founders and its leading organisers, with a few exceptions, were Maharashtrian Brahmins from the middle or lower class[207] and argues that the pervasiveness of the Brahminical ethic in the organisation was probably the main reason why it failed to attract support from the low castes. He argues that the "RSS resorted to instrumentalist techniques of ethnoreligious mobilisation—in which its Brahminism was diluted—to overcome this handicap".[208] However, Anderson and Damle (1987) find that members of all castes have been welcomed into the organisation and are treated as equals.[12]

During a visit in 1934 to an RSS camp at Wardha accompanied by Mahadev Desai and Mirabehn, Mahatma Gandhi said, "When I visited the RSS Camp, I was very much surprised by your discipline and absence of untouchability." He personally inquired about this to Swayamsevaks and found that volunteers were living and eating together in the camp without bothering to know each other's castes.[209]

Relief and rehabilitation

The RSS was instrumental in relief efforts after the 1971 Odisha cyclone, 1977 Andhra Pradesh cyclone[210] and in the 1984 Bhopal disaster.[211][212] It assisted in relief efforts during the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, and helped rebuild villages.[210][213] Approximately 35,000 RSS members in uniform were engaged in the relief efforts,[214] and many of their critics acknowledged their role.[215] An RSS-affiliated NGO, Seva Bharati, conducted relief operations in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. Activities included building shelters for the victims and providing food, clothes, and medical necessities.[216] The RSS assisted relief efforts during the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake and the subsequent tsunami.[217] Seva Bharati also adopted 57 children (38 Muslims and 19 Hindus) from militancy affected areas of Jammu and Kashmir to provide them education at least up to Higher Secondary level.[218][219] They also took care of victims of the Kargil War of 1999.[220]

During the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, as per the former National Minorities Commission chairman Tarlochan Singh and noted journalist & author Khushwant Singh, RSS activists also protected and helped members of the Sikh community.[221][222][223][broken footnote][224]

In 2006 RSS participated in relief efforts to provide basic necessities such as food, milk, and potable water to the people of Surat, Gujarat, who were affected by floods in the region.[citation needed] The RSS volunteers carried out relief and rehabilitation work after the floods affected North Karnataka and some districts of the state of Andhra Pradesh.[225] In 2013, following the Uttarakhand floods, RSS volunteers were involved in flood relief work through its offices set up at affected areas.[226][227]

Backing the 2020 coronavirus lockdown in India, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh provided essential services including masks, soaps and food to many all over India during the lockdown.[228][229][230] In 2020, a Muslim woman from Jammu and Kashmir donated all her savings meant for her Hajj pilgrimage, worth ₹5 lakh, to the RSS-affiliated 'Sewa Bharati' after being "impressed with the welfare work" done by the outfit amid the lockdown due to the novel coronavirus pandemic.[231] The number of Muslim students in the schools run by Vidya Bharati, the educational wing of RSS, has witnessed an increase of approximately 30% during the three years 2017–2020 in Uttar Pradesh.[232]

Publications

Two prominent publications of the RSS are Panchajanya (Hindi) and Organiser (English). The first magazines published were Rashtra Dharma (Hindi) and Organiser (English). Later in 1948 new publications were launched, Panchajanya from Lucknow, Akashwani from Jalandhar and Chetana from Varanasi. Until 1977 the publications were published by Rashtra Dharma Prakashan the responsibility of which was later taken over by Bharat Prakashan Ltd. The governing board of the publications has been appointing editors for the publications. Prominent leaders like Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay, former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee have been the editors of these publications.[233][234] In 2013, the number of subscriptions to Panchajanya was around 60,000 and around 15,000 for Organiser. Subscriptions have increased substantially after 2014 election of Narendra Modi as the Prime minister. As of 2017[update], Panchajanya had more than 1 lakh subscribers and Organiser had 25,000.[235]

Criticism

The RSS has been criticised as an extremist organisation and as a paramilitary group.[27][236][237] It has also been criticised when its members have participated in anti-Muslim violence;[238] it has since formed in 1984, a militant wing called the Bajrang Dal.[17][239] Along with Shiv Sena, the RSS has been involved in riots, often inciting and organising violence against Christians and Muslims.[240][10] Thus, there is a common consensus among the academia and intellectuals that RSS spreads hatred.[241][242][243][244][245][246]

Terrorism

The RSS has been criticised for promoting and planning terrorist attacks, and numerous such attacks have been linked to RSS members. In November 2003, two bombs planted by RSS members killed one person and injured thirty-four others at a mosque in Parbhani, Maharashtra. Another such bombing killed sixty-eight people, mostly Pakistanis, on a train running between India and Pakistan. On 29 September 2008, a bomb planted by terrorists linked to the RSS exploded in Malegaon, Maharashtra, in an area where Muslims were breaking their Ramadan fasts, killing six and injuring 101. It is believed that between 2003 and 2008, nine terror attacks linked to the RSS or other Sanghi Parivar organisations killed almost 150 people, mostly Muslims; many of these attacks happened near or inside Muslim places of worship or on Islamic holidays.[247]

In September 2022, former pracharak (full-time worker) in the RSS Yashwant Shinde revealed in an interview and a sworn affidavit he was trained to carry out covert operations in Pakistan as well as false flag terrorist attacks in India that could then be used to scapegoat Muslims. He alleged that he and his fellow trainees have bombed mosques in Jalna, Purna, and Parbhani in Maharashtra. Shinde has implicated key members of the RSS and the larger Sanghi Pariwar in directly planning or having knowledge of these attacks, including a former RSS national executive member and a national secretary of the BJP.[248] Shinde asserted that the goal of many of these operations was to promote Islamophobia among Hindus by strengthening the stereotype of violent Muslim terrorists and thereby gaining support for the BJP and Hindu nationalist agendas. A statement by India’s National Investigation Agency corroborated this claim, stating that the bombings "were caused by the conspirators with an intention to terrorize people...to create communal rift" between Hindus and Muslims.[247][248]

Involvement with riots

The RSS has been censured for its involvement in communal riots.

After giving careful and serious consideration to all the materials that are on record, the Commission is of the view that the RSS with its extensive organisation in Jamshedpur and which had close links with the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh had a positive hand in creating a climate which was most propitious for the outbreak of communal disturbances.

In the first instance, the speech of Shri Deoras (delivered just five days before the Ram Navami festival) tended to encourage the Hindu extremists to be unyielding in their demands regarding Road No. 14. Secondly, his speech amounted to communal propaganda. Thirdly, the shakhas and the camps that were held during the divisional conference presented a militant atmosphere to the Hindu public. In the circumstances, the commission cannot but hold the RSS responsible for creating a climate for the disturbances that took place on 11 April 1979.

Jitendra Narayan Commission report on Jamshedpur riots of 1979[249][relevant? – discuss]

Human Rights Watch, a non-governmental organisation for human rights based in New York, has claimed that the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (World Hindu Council, VHP), the Bajrang Dal, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, and the BJP have been party to the Gujarat violence that erupted after the Godhra train burning.[250] Local VHP, BJP, and BD leaders have been named in many police reports filed by eyewitnesses.[251] RSS and VHP claimed that they made appeals to put an end to the violence and that they asked their supporters and volunteer staff to prevent any activity that might disrupt peace.[252][253]

Religious violence in Odisha

Christian groups accuse the RSS alongside its close affiliates, the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Bajrang Dal (BD), and the Hindu Jagaran Sammukhya (HJS), of participation in the 2008 religious violence in Odisha.[254]

Involvement in the Babri Masjid demolition

According to the 2009 report of the Liberhan Commission, the Sangh Parivar organised the destruction of the Babri Mosque.[238][255] The Commission said: "The blame or the credit for the entire temple construction movement at Ayodhya must necessarily be attributed to Sangh Parivar."[256] It also noted that the Sangh Parivar is an "extensive and widespread organic body" that encompasses organisations that address and bring together just about every type of social, professional, and other demographic groupings of individuals. The RSS has denied responsibility and questioned the objectivity of the report. Former RSS chief K. S. Sudarshan alleged that the mosque had been demolished by government men as opposed to the Karsevak volunteers. On the other hand, a government of India white paper dismissed the idea that the demolition was pre-organised.[257] The RSS was banned after the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition, when the government of the time considered it a threat to the state. The ban was subsequently lifted in 1993 when no evidence of any unlawful activity was found by the tribunal constituted under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.[258]

Involvement in politics

Several Sangh Parivar politicians such as Balraj Madhok in the 1960s and 1970s to the BJP leaders like L. K. Advani have complained about the RSS's interference in party politics. Though some former Hindu nationalists believed that Sangh should take part in politics, they failed to draw the RSS, which was intended to be a purely cultural movement, into the political arena until the 1950s. Savarkar tried to convince Hedgewar and later Golwalkar, to tie up with the Hindu Mahasabha, but failed to do so.[259]

Under pressure from other swayamsevaks, Golwalkar gradually changed his mind after independence under unusual circumstances during the ban on RSS in 1948 after the assassination of Gandhi. After the first wave of arrests of RSS activists at that time, some of its members who had gone underground recommended that their movement be involved in politics, seeing that no political force was present to advocate the cause of RSS in parliament or anywhere else. One such member who significantly suggested this cause was K. R. Malkani, who wrote in 1949:[259]

Sangh must take part in politics not only to protect itself against the greedy design of politicians, but to stop the un-Bharatiya and anti-Bharatiya policies of the Government and to advance and expedite the cause of Bharatiya through state machinery side by side with official effort in the same direction. ... Sangh must continue as it is, an ashram for the national cultural education of the entire citizenry, but it must develop a political wing for the more effective and early achievement of its ideals.

Golwalkar approved of Malkani's and others' views regarding the formation of a new party in 1950. Jaffrelot says that the death of Sardar Patel influenced this change since Golwalkar opined that Patel could have transformed the Congress party by emphasising its affinities with Hindu nationalism, while after Patel, Nehru became strong enough to impose his 'anti-communal' line within his party. Accordingly, Golwalkar met Syama Prasad Mukherjee and agreed for endorsing senior swayamsevaks, who included Deendayal Upadhyaya, Balraj Madhok and Atal Bihari Vajpayee, to the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, a newly formed political party by Mukherjee. These men, who took their orders from RSS, captured power in the party after Mukherjee's death.[259]

Balasaheb Deoras, who succeeded Golwalkar as the chief of RSS, got very much involved in politics. In 1965, when he was the general secretary of the RSS, he addressed the annual meeting of Jana Sangh, which is seen as an "unprecedented move" by an RSS dignitary that reflected his strong interest in politics and his will to make the movement play a larger part in the public sphere. Jaffrelot says that he exemplified the specific kind of swayamsevaks known as 'activists', giving expression to his leanings towards political activism by having the RSS support the JP Movement.[259] The importance that RSS began to give to the electoral politics is demonstrated when its shakhas were made constituency-based in the early 1970s, from which the RSS shakhas began to involve directly in elections, not only of legislatures, but also of trade unions, student and cultural organisations.[114]

As soon as the RSS men took over the Jana Sangh party, the Hindu traditionalists who previously joined the party because of S. P. Mukherjee were sidelined.[citation needed] The organisation of the party was restructured and all its organisational secretaries, who were the pillars of the party, came from the RSS, both at the district and state level. The party also took the vision of RSS in its mission, where its ultimate objective, in the long run, was the reform of society, but not the conquest of power, since the 'state' was not viewed as a prominent institution. Hence the Jana Sangh initially remained reluctant to join any alliance that was not fully in harmony with its ideology. In 1962, Deendayal Upadhyaya, who was the party's chief, explained this approach by saying that "coalitions were bound to degenerate into a struggle for power by opportunist elements coming together in the interest of expediency". He wanted to build the party as an alternative party to the Congress and saw the elections as an "opportunity to educate the people on political issues and to challenge the right of the Congress to be in power". Jaffrelot says that this indifferent approach of party politics was in accordance with its lack of interest in the 'state' and the wish to make it weaker, or more decentralised.[259] After India's defeat in the 1962 Sino–Indian war, the RSS and other right-wing forces in India were strengthened since the leftist and centrist opinions, sometimes even Nehru himself, could then be blamed for being 'soft' towards China. The RSS and Jana Sangh also took complete advantage of the 1965 war with Pakistan to "deepen suspicion about Muslims", and also en-cashed the growing unpopularity of Congress, particularly in the Hindi-belt, where a left-wing alternative was weak or non-existent.[114] The major themes on the party's agenda during this period were banning cow slaughter, abolishing the special status given to Jammu and Kashmir, and legislating a uniform civil code. Explaining the Jana Sangh's failure to become a major political force despite claiming to represent the national interests of the Hindus, scholar Bruce Desmond Graham states that the party's close initial ties with the Hindi-belt and its preoccupation with the issues of North India such as promotion of Hindi, energetic resistance to Pakistan etc., had become a serious disadvantage to the party in the long run. He also adds that its interpretation of Hinduism was "restrictive and exclusive", arguing that "its doctrines were inspired by an activist version of Hindu nationalism and, indirectly, by the values of Brahmanism rather than the devotional and quietist values of popular Hinduism."[260] Desmond says that, if the Jana Sangh had carefully moderated its Hindu nationalism, it could have been able to well-exploit any strong increase in support for the traditional and nationalist Hindu opinion, and hence to compete on equal terms with the Congress in the northern states. He also remarks that if it had adopted a less harsh attitude towards Pakistan and Muslims, "it would have been much more acceptable to Hindu traditionalists in the central and southern states, where partition had left fewer emotional scars."[261]

The Jana Sangh started making alliances by entering the anti-Congress coalitions since the 1960s. It became part of the 1971 Grand Alliance and finally merged itself with the Janata Party in 1977.[259] The success of Janata Party in 1977 elections made the RSS members central ministers for the first time (Vajpayee, Advani and Brij Lal Verma),[114] and provided the RSS with an opportunity to avail the state and its instruments to further its ends, through the resources of various state governments as well as the central government.[262] However, this merge, which was seen as a dilution of its original doctrine, was viewed by the ex-Jana Sanghis as submersion of their initial identity. Meanwhile, the other components of the Janata Party denounced the allegiance the ex-Jana Sanghis continued to pay to the RSS. This led to a 'dual membership' controversy, regarding the links the former Jana Sangh members were retaining with the RSS, and it led to the split of Janata Party in 1979.[259]

The former Jana Sangh elements formed a new party, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), in 1980. However, BJP originated more as a successor to the Janata Party and did not return to the beginning stages of the Hindu nationalist identity and Jana Sangh doctrines. The RSS resented this dilution of ideology – the new slogans promoted by the then BJP president Vajpayee like 'Gandhian socialism' and 'positive secularism'. By the early 1980s, RSS is said to have established its political strategy of "never keeping all its eggs in one basket". It even decided to support Congress in some states, for instance, to create the Hindu Munnani in Tamil Nadu in the backdrop of the 1981 Meenakshipuram mass conversion to Islam, and to support one of its offshoots, Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), to launch an enthno-religious movement on the Ayodhya dispute. BJP did not have much electoral success in its initial years and was able to win only two seats in the 1984 elections. After L. K. Advani replaced Vajpayee as party president in 1986, the BJP also began to rally around the Ayodhya campaign. In 1990, the party organised the Ram Rath Yatra to advance this campaign in large-scale.[259][114] Advani also attacked the then ruling Congress party with the slogans such as 'pseudo-secularism', accusing Congress of misusing secularism for the political appeasement of minorities, and established an explicit and unambiguous path of Hindu revival.[119]

The 'instrumentalisation' of the Ayodhya issue and the related communal riots which polarised the electorate along religious lines helped the BJP make good progress in the subsequent elections of 1989, 1991 and 1996. However, in the mid-1990s, BJP adopted a more moderate approach to politics in order to make allies. As Jaffrelot remarks, it was because the party realised during then that it would not be in a position to form the government on its own in the near future. In 1998, it built a major coalition, National Democratic Alliance (NDA), in the Lok Sabha and succeeded in the general election in 1998, and was able to succeed again in the mid-term elections of 1999, with Vajpayee as their Prime Ministerial candidate. Though the RSS and other Sangh Parivar components appreciated some of the steps taken by the Vajpayee government, like the testing of a nuclear bomb, they felt disappointed with the government's overall performance. The fact that no solid step was taken towards building the Ram temple in Ayodhya was resented by the VHP. The liberalisation policy of the government faced objection from the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, a trade union controlled by the RSS. Jaffrelot says, RSS and the other Sangh Parivar elements had come to the view that the "BJP leaders had been victims of their thirst for power: they had preferred to compromise to remain in office instead of sticking to their principles."[263]

After the end of Vajpayee's tenure in 2004, BJP remained as a major opposition party in the subsequent years; and again in the year 2014, the NDA came to power after BJP gained an overwhelming majority in the 2014 general elections, with Narendra Modi, a former RSS member who previously served as Gujarat's chief minister for three tenures, as their prime ministerial candidate. Modi was able to project himself as a person who could bring about "development", without focus on any specific policies,[264] through the "Gujarat development model" which was frequently used to counter the allegations of communalism.[265] Voter dissatisfaction with the Congress, as well as the support from RSS are also stated as reasons for the BJP's success in the 2014 elections.[264]

See also

References

- ^ Embree, Ainslie T. (2005). "Who speaks for India? The Role of Civil Society". In Rafiq Dossani; Henry S. Rowen (eds.). Prospects for Peace in South Asia. Stanford University Press. pp. 141–184. ISBN 0804750858.

- ^ a b c Jaffrelot, Christophe (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. p. 46. ISBN 9789380607047.

- ^ Priti Gandhi (15 May 2014). "Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh: How the world's largest NGO has changed the face of Indian democracy". DNA India. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "Hindus to the fore". Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Glorious 87: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh turns 87 on today on Vijayadashami". Samvada. 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "Highest growth ever: RSS adds 5,000 new shakhas in last 12 months". The Indian Express. 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)". Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

(Hindi: "National Volunteer Organisation") also called Rashtriya Seva Sangh

- ^ a b Johnson, Matthew; Garnett, Mark; Walker, David M. (2017), Conservatism and Ideology, Routledge, p. 77, ISBN 978-1-317-52899-9, retrieved 25 March 2021,

A couple of years later, India was ruled by the Janata coalition, which consisted also of Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), the then-political arm of the extreme right-wing Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS – National Volunteers Organisation).

- ^ a b Pal, Felix; Chaudhary, Neha (4 March 2023). "Leaving the Hindu Far Right". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 46 (2): 425–444. doi:10.1080/00856401.2023.2179817. ISSN 0085-6401. S2CID 257565310.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Donald L. (2001). The Deadly Ethnic Riot. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0520224476.

- ^ Jeff Haynes (2 September 2003). Democracy and Political Change in the Third World. Routledge. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-1-134-54184-3. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Andersen & Damle 1987, p. 111.

- ^ McLeod, John (2002). The history of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-0-313-31459-9. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Jain, Rupam; Chaturvedi, Arpan (11 January 2023). "Leader of influential Hindu group backs LGBT rights in India". Reuters. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, p. 362.

- ^ Andersen & Damle 1987, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Atkins, Stephen E. (2004). Encyclopedia of modern worldwide extremists and extremist groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 264–265. ISBN 978-0-313-32485-7. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Dina Nath Mishra (1980). RSS: Myth and Reality. Vikas Publishing House. p. 24. ISBN 978-0706910209.

- ^ Singh, Amit (31 October 2022). "🌊 Hindutva fascism threatens the world's largest democracy". The Loop. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (20 September 2022). "What is Hindu nationalism and how does it relate to trouble in Leicester?". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ a b Lal, Vinay (2003). The History of History: Politics and Scholarship in Modern India. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-566465-2.

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the paramilitary organization which advocates a militant Hinduism and a Hindu polity in modern India, not only played no role in the anti-colonial struggle but actively collaborated with the British.

- ^ a b c Bhatt, Hindu Nationalism 2001, p. 99"RSS was not considered an adversary by the British. On the contrary, it gave loyal consent to the British to be part of the Civic Guard."

- ^ Verma, M.L. (2006). स्वाधीनता संग्राम के क्रान्तिकारी साहित्य का इतिहास [On the History of Indian Freedom Movements According to Related Literature] (in Hindi). Vol. 3. Praveen Publications. p. 766.

- ^ a b —Karawan, Ibrahim A.; McCormack, Wayne; Reynolds, Stephen E. (2008). Values and Violence: Intangible Aspects of Terrorism. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4020-8660-1.

—Venugopal, Vasudha (8 September 2016). "Nathuram Godse never left RSS, says his family". The Economic Times. - ^ "RSS releases 'proof' of its innocence". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 18 August 2004. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ a b James Larson, Gerald (1995). India's Agony Over Religion. State University of New York Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-7914-2412-X.

- ^ a b c Curran, Jean A. (17 May 1950). "The RSS: Militant Hinduism". Far Eastern Survey. 19 (10): 93–98. doi:10.2307/3023941. JSTOR 3023941.

- ^ a b c Goodrick-Clarke 1998, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 33–39.

- ^ a b c Kelkar 2011, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Bhishikar 1979.

- ^ a b c Kelkar 1950, p. 138.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, p. 249.

- ^ a b c Andersen, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: Early Concerns 1972.

- ^ Anand, Arun (2020). The Saffron Surge Untold Story of RSS Leadership. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 23. ISBN 978-93-5322-265-9. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Hutchinson, J.; Smith, A.D. (2000). Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. Routledge. p. 926. ISBN 978-0-415-20112-4.

Khilafat movement which was primarily designed to prevent the allied dismemberment of Turkey after World War One.

- ^ Stern, Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia (2001), p. 27. Quote: '... mobilization of Indian Muslims in the name of Islam and in defense of the Ottoman khalifa was inherently "communal", no less than the Islamic movements of opposition to British imperialism which preceded it.... All defined a Hindu no less than a British "other".'

- ^ Stern, Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia (2001); Misra, Identity and Religion: Foundations of Anti-Islamism in India (2004)

- ^ Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 40.

- ^ Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, p. 250.

- ^ a b Basu & Sarkar, Khaki Shorts and Saffron Flags 1993, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Frykenberg 1996, p. 241.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, Chapter 1.

- ^ Bapu 2013, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Goyal 1979, pp. 59–76.

- ^ "RSS aims for a Hindu nation". BBC News. 10 March 2003. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Nussbaum, The Clash Within 2008, p. 156.

- ^ a b Bhatt, Hindu Nationalism 2001, p. 115.

- ^ Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 188.

- ^ a b Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, pp. 251–254.

- ^ Tapan Basu, Khaki Shorts 1993, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d R. Hadiz, Vedi (27 September 2006). Empire and Neoliberalism in Asia. Routledge. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-134-16727-2. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Puniyani, Religion, Power and Violence 2005, p. 141.

- ^ Puniyani, Religion, Power and Violence 2005, p. 129.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 74.

- ^ a b Golwalkar, M.S. (1974). श्री गुरुजी समग्र [Sir Guruji Overall] (in Hindi). Vol. 4. Bharatiya Vichar Sadhana.

- ^ Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 191.

- ^ Puniyani, Religion, Power and Violence 2005, p. 135.

- ^ Tapan Basu, Khaki Shorts 1993, p. 29.

- ^ Ludden, David (1 April 1996). Contesting the Nation: Religion, Community, and the Politics of Democracy in India. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 274–. ISBN 0-8122-1585-0. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ a b Andersen & Damle 1987.

- ^ a b Noorani, RSS and the BJP 2000, p. 46.

- ^ Bipan Chandra, Communalism 2008, p. 140.

- ^ a b Bandyopadhyaya, Sekhara (1 January 2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Blackswan. p. 422. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Bipan Chandra, Communalism 2008, p. 141.

- ^ Noorani, RSS and the BJP 2000, p. 60.

- ^ Sarkar, Sumit (2005). Beyond Nationalist Frames: Relocating Postmodernism, Hindutva, History. Permanent Black. pp. 258–. ISBN 978-81-7824-086-2. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ Sarathi Gupta, Partha (1997). Towards Freedom 1943–44, Part III. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 3058–9. ISBN 978-0195638684.

- ^ Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 187.

- ^ "India". Users.erols.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Bose, Sumantra (16 September 2013). Transforming India. Harvard University Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 9780674728196.