Search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

The disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370[a] led to a multinational search effort in Southeast Asia and the southern Indian Ocean that became the most expensive search in aviation history.[2]

Despite delays, the search of the priority search area was to be completed around May 2015.[3] On 29 July 2015, a piece of marine debris, later confirmed to be a flaperon from Flight 370, was found on Réunion Island.[4][5][6]

On 20 December 2016, it was announced that an unsearched area of around 25,000 square kilometres (9,700 sq mi), and approximately centred on location 34°S 93°E / 34°S 93°E, was the most likely impact location for flight MH370.[7] The search was suspended on 17 January 2017.[8] In October 2017, the final drift study believed the most likely impact location to be at around 35°36′S 92°48′E / 35.6°S 92.8°E. The search based on these coordinates was resumed in January 2018 by Ocean Infinity, a private company; it ended in June 2018 without success.

Ships and aircraft from Malaysia, China, India, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Vietnam, the United Kingdom, and the United States were involved in the search of the southern Indian Ocean. Satellite imagery was also made available by Tomnod to the general public so they could help with the search through crowdsourcing efforts.

Ocean Infinity has requested approval from the Malaysian government to resume the search, with an expected date of commencement from November 2024, but the search has not started as of January 2025.[9][10] The plan, submitted in June 2024, would continue the search over 15,000 square kilometres (5,800 sq mi) off the coast of Western Australia.[11]

In December 2024, it was reported that Ocean Infinity would resume the search for the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 under a $70 million 'no find, no fee' agreement with the Malaysian government.[12]

Disappearance

[edit]| Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 |

|---|

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 was a scheduled flight in the early morning hours of 8 March 2014 from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia to Beijing, China—one of two daily flights operated by Malaysia Airlines from its hub at Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) to Beijing Capital International Airport. Flight 370 was scheduled to depart at 00:35 local time (MYT; UTC+08:00) and arrive at 06:30 local time (CST; UTC+08:00).[13][14] At 00:41 MYT, Flight 370 took off with 239 occupants aboard—two pilots, ten cabin crew, and 227 passengers (152 of whom were Chinese citizens).[15]: 1, 12, 30 Flight 370 was cleared by air traffic control to proceed on a direct path to waypoint IGARI (6°56′12″N 103°35′6″E / 6.93667°N 103.58500°E), located between Malaysia and Vietnam over the South China Sea (near the boundary with the Gulf of Thailand).[15]: 1

At 01:07 MYT, the aircraft was at flight level 350—approximately 35,000 feet (11,000 m) above sea level—when the final message using the ACARS protocol was sent from the aircraft.[16]: 2 At 1:19 MYT, Lumpur area air traffic control (ATC) initiated a hand-off to Ho Chi Minh area ATC. The Captain[15]: 21 responded "Good night Malaysian Three Seven Zero,"[17] (originally reported to have been "all right, good night"), after which no further communications were made with the pilots.[17] The crew was expected to contact air traffic control in Ho Chi Minh City as the aircraft passed into Vietnamese airspace just north of the point where the final verbal communication was made.[18] Less than two minutes later, at 01:21, the aircraft disappeared from the radar screens of both Malaysian and Vietnamese ATC, which use secondary radar to track aircraft.[15]: 2 No distress call was made.[19]

Flight 370 was expected to arrive in Beijing at 6:30 local time (same time zone as Malaysia; 22:30 UTC, 7 March). At 7:24, Malaysia Airlines issued a media statement that Flight 370 was missing after contact was lost with Malaysian ATC at 2:40. The time of the last contact with ATC was later corrected to 1:19; Malaysia Airlines was notified at 2:40.[18]

Initial search in Southeast Asia (March 2014)

[edit]

The watch supervisor at Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre—which was the air traffic control centre that was last in contact with Flight 370—activated the Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC) at 05:30, over four hours after communication was lost with Flight 370.[20][21] When Malaysia Airlines issued a media statement two hours later, they claimed that they were "working with the authorities who have activated their Search and Rescue team to locate the aircraft".[22]

On 9 March, the Chief General of the Royal Malaysian Air Force announced that Malaysia was analysing military radar recordings and that there was a "possibility"[23] that Flight 370 had turned around and travelled over the Andaman Sea.[23][24][25] The search radius was increased from the original 20 nmi (37 km; 23 mi) from its last known position,[26] south of Thổ Chu Island, to 100 nmi (190 km; 120 mi), and the area being examined then extended to the Strait of Malacca along the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, with waters both to the east of Malaysia in the Gulf of Thailand, and in the Strait of Malacca along Malaysia's west coast, being searched.[23][27][28]

Numerous sightings of possible debris were made, but no debris from Flight 370 was discovered.[29] Offshore oil slicks near Vietnam on 9 and 10 March later tested negative for aviation fuel.[29][30] Satellite images taken on 9 March and posted on a Chinese website showed three floating objects measuring up to 24 × 22 metres (79 × 72 ft) at 6°42′N 105°38′E / 6.7°N 105.63°E, but a search of the area did not find the objects;[31][32] Vietnamese officials said the area had been "searched thoroughly".[33][34] By the end of 9 March, 40 aircraft and more than two dozen vessels from several nations were involved in the search.[35]

The Royal Malaysian Air Force confirmed on 10 March that Flight 370 made a "turn back".[36] The following day, China activated the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters to aggregate satellite data to aid the search.[37][38] On 12 March, Malaysian officials announced that an unidentified aircraft, possibly Flight 370, was last located by military radar at 2:15 in the Andaman Sea, 320 kilometres (200 mi) northwest of Penang Island and near the limits of the military radar's coverage.[39] The focus of the search shifted to the Andaman Sea and the Malaysian government requested help from India to search in the area.[40]

International involvement

[edit]The Malaysian government mobilised its civil aviation department, air force, navy, and Maritime Enforcement Agency; and requested international assistance under Five Power Defence Arrangements provisions and from neighbouring states. Various nations mounted a search and rescue mission in the region's waters.[41][42] Within two days, the countries had already dispatched more than 34 aircraft and 40 ships to the area.[23][27][43]

On 11 March, the China Meteorological Administration[44] activated the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters, a 15-member organization whose purpose is to "provide a unified system of space data acquisition and delivery to those affected by natural or man-made disasters",[45] the first time the charitable and humanitarian redeployment of the assorted corporate, national space agency, and international satellite assets under its aegis had been used to search for an airliner.[46]

Another 11 countries joined the search efforts by 17 March after more assistance was requested by Malaysia.[47] At the peak of the search effort and before the search was moved to the south Indian Ocean, 26 countries were involved in the search, contributing in aggregate nearly 60 ships and 50 aircraft. In addition to the countries already named, these parties included Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei, Cambodia, China, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Myanmar, New Zealand, Norway, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, and Vietnam.[48][49] While not participating in the search itself, Sri Lanka gave permission for search aircraft to use its airspace.[50] Malaysia deployed military fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, and ships.[51][52][53] A co-ordination centre at the National Disaster Control Centre (NDCC) in Pulau Meranti, Cyberjaya, was established.[54]

On 16 March, three staff members of the French government agency BEA flew to Kuala Lumpur to share with Malaysian authorities their experience in the organisation of undersea searches, acquired during the search for the wreckage of Air France Flight 447.[55] The United Kingdom provided technical assistance and specialist capabilities from the Ministry of Defence, the UK Hydrographic Office, Department for Transport and the Met Office.[56] The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization Preparatory Commission analysed information from its network of infrasound detection stations, but failed to find any sounds made by Flight 370.[57]

Satellite communications and radar

[edit]

On 11 March, New Scientist reported that, prior to the aircraft's disappearance, two reports about the engine status using the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) protocol had been automatically sent to engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce's monitoring centre in the United Kingdom.[58]

On 12 March, it was reported that military radar indicated the aircraft turned west away from the intended flight path and continued flying for 70 minutes before disappearing from Malaysian radar near Pulau Perak.[59][60] It was also reported that it had been tracked flying at a lower altitude across Malaysia to the Malacca Strait, approximately 500 kilometres (310 mi) from its last contact with civilian radar.[61] The next day, the Royal Malaysian Air Force chief denied the report.[62][63] A few hours later, however, the Vietnamese transport minister claimed that Malaysia had been informed on 8 March by Vietnamese air traffic control personnel, that they had "noticed the flight turned back west".[64] A U.S. radar expert analysing the radar data reported that they did indeed indicate that the aircraft had headed west across the Malay Peninsula.[65] The New York Times reported that the aircraft experienced significant changes in altitude.[66][67]

On 13 March, The Wall Street Journal, citing sources in the US government, asserted that Rolls-Royce had received an aircraft health report every thirty minutes for five hours, implying that the aircraft had remained aloft for four hours after its transponder went offline;[68][69][70] Malaysia denied the report.[70] The Wall Street Journal later amended its report and stated simply that the belief of continued flight was "based on analysis of signals sent by the Boeing 777's satellite-communication link... the link operated in a kind of standby mode and sought to establish contact with a satellite or satellites. These transmissions did not include data."[66][71] The following day, satellite operator Inmarsat released a public statement stating that "routine, automated signals were registered" on its network;[72] analysis of these "keep-alive message[s]" that continued to be sent after air traffic control first lost contact could help pinpoint the aircraft's location.[73]

At a press conference on 15 March, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak confirmed that satellite communications from Flight 370 continued for several hours after contact with it was lost over the South China Sea and that the last signal—received at 08:11 Malaysian time—might have originated from as far north as Kazakhstan.[74] Najib explained that the signals could not be more precisely located than to one of two possible loci: a northern locus stretching approximately from the border of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to northern Thailand, or a southern locus stretching from Indonesia to the southern Indian Ocean.[75][76] Many of the countries on a possible northerly flight route—China, Thailand, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, and India—denied the aircraft could have entered their country's airspace, because military radar would have detected it.[77] Inmarsat had provided an initial analysis of the signals from Flight 370, which produced the two loci, on 11 March.[78]

Malaysian authorities appealed to the U.S. to share if its Pine Gap satellite ground station or Jindalee (JORN) radar site might have data to help locate the missing aircraft.[79][80]

Shift to the Southern Indian Ocean (March–May 2014)

[edit]

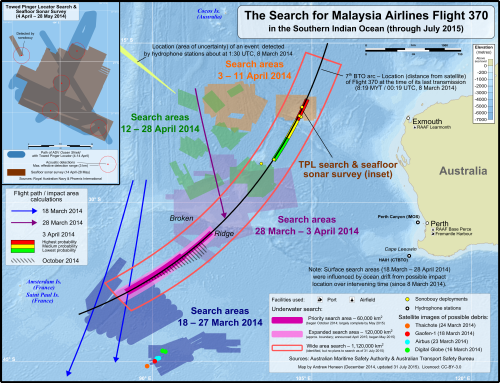

In the wake of the 15 March press conference, the focus of the search shifted to the southern part of the Indian Ocean, west of Australia.[16]: 1 In the first two weeks of April, aircraft and ships deployed equipment to listen for signals from the underwater locator beacons attached to the aircraft's "black boxes". Four unconfirmed signals were detected between 6 and 8 April near the time the beacons' batteries were likely to have been exhausted. A robotic submarine searched the seabed near the detected pings until 28 May, with no debris found.[81]

Surface search

[edit]On 17 March, Australia agreed to lead the search in the southern locus from Sumatra to the southern Indian Ocean.[82][83] The search would be coordinated by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), with an area of 600,000 km2 (230,000 sq mi) between Australia and the Kerguelen Islands lying more than 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi) southwest of Perth, to be searched by ships and aircraft of Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.[84] This remote area, which Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott described as "as close to nowhere as it's possible to be", is renowned for its strong winds, inhospitable climate, hostile seas, and deep ocean floors.[85][86] On 18 March, the search of the area began with a single Royal Australian Air Force P-3 Orion aeroplane.[87] On 19 March, the search capacity was ramped up to three aircraft and three merchant ships;[88] the revised search area of 305,000 square kilometres (118,000 sq mi) was about 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) south-west of Perth.[89]

Search efforts intensified on 20 March, after large pieces of possible debris had been photographed in this area four days earlier by a satellite.[90][91][92][93][94] Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea assigned military and civilian ships and aircraft to the search.[95][96] China published images from satellite Gaofen 1 on 22 March that showed large debris about 120 km (75 mi) south west of the previous sighting.[97][98][99] The same day, HMAS Success became the first naval vessel to reach the search area.[100] On 26 March, images from French satellites indicated 122 floating objects in the southern Indian Ocean.[101][102] Thai satellite images published on 27 March showed about 300 floating objects about 200 km (120 mi) from the French satellites' target area.[103] The abundant finds, none confirmed to be from the flight, brought the realisation of the prior lack of surveillance over the area, and the vast amounts of marine debris littering the oceans.[104][105]

On 28 March, revised estimates of the radar track and the aircraft's remaining fuel led to a move of the search 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) north-east of the previous area,[106][107] to a new search area of 319,000 square kilometres (123,000 sq mi), roughly 1,850 kilometres (1,150 mi) west of Perth.[108][109][110][111] This search area had more hospitable weather conditions.[98]

On 30 March, four large orange objects found by search aircraft, described by media as "the so far most promising lead", turned out to be fishing equipment.[112] On 2 April, Royal Navy survey vessel HMS Echo and submarine HMS Tireless arrived in the area,[113] with HMS Echo starting immediately to search for the aircraft's underwater locator beacons (ULBs) fitted to the "black box" flight recorders,[114] whose batteries were expected to expire around 7 April.[115][116] On 4 April, the search area was shifted further north.[117][118]

The surface search ended on April 28. In a press conference, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott noted that any debris would likely have become waterlogged and sunk and that the aircraft involved in the surface search were "operating at close to the limit of sensible and safe operation".[119] Abbott explained that it was "highly unlikely" that any surface wreckage would be found and, therefore, the aerial searches had been suspended.[119][120][121] The surface search in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean lasted 52 days, during 41 of which Australia coordinated the search. Over 4,500,000 km2 (1,700,000 sq mi) of ocean surface was searched. In the Southern Indian Ocean, 29 aircraft from seven countries conducted 334 search flights; 14 ships from several countries were also involved.[119][120][121]

Underwater locator beacon search

[edit]On 4 April, the search was refocused to three more northerly areas from 1,060 to 2,100 kilometres (660 to 1,300 mi) west of Learmonth, spanning over 217,000 square kilometres (84,000 sq mi).[117][118] ADV Ocean Shield, fitted with a TPL-25 towed pinger locator, together with HMS Echo—which carried a "similar device", began searching for pings along a 240-kilometre (150 mi) seabed line believed to be the Flight 370 impact area.[115][122][123] Operators considered it a shot in the dark, when comparing the vast search area with the fact that TPL-25 could only search up to 130 square kilometres (50 sq mi) per day.[124]

The Chinese vessel Haixun 01 made a possible ULB detection at 25°58′30″S 101°27′40″E / 25.975°S 101.461°E[125] using a handheld hydrophone;[126][127][128][129] the following day, Haixun 01 made another possible ULB detection about 3 km (1.9 mi) further west. HMS Echo and a submarine were later tasked to the location of the Haixun 01's detections, but unable to make any detections.[16]: 11

On 6 April, JACC announced that Ocean Shield had also picked up a signal, about 300 nautical miles (560 km; 350 mi) from Haixun 01.[130][131] It was announced the next day that the TPL-25 pinger locator towed by Ocean Shield had picked up a signal twice on 6 April.[132][133] The first was on the morning of 6 April, at approximately 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) depth, and lasted two hours and 20 minutes. The second signal reception took place at approximately 300 metres (980 ft) depth and lasted 13 minutes. During the second episode, two distinct pinger returns were audible. Both episodes of recorded signals, which took place at roughly the same position though several kilometres apart, were considered to be consistent with signals expected from an aircraft's flight recorder ULB.[134] The signals received by Ocean Shield were recorded at the north of a newly calculated impact area, which was announced on 7 April, while the Haixun 01 signals had been recorded at its southern edge.[134][135][136] Ocean Shieldtwo more signals on 8 April. The first was acquired at 16:27 AWST and held for 5 minutes, 32 seconds and the second was acquired at 22:17 AWST and held for around seven minutes.[137][138][139] Experts had determined that the earlier signals captured by Ocean Shield were "very stable, distinct, and clear ... at 33.331 kHz and ... consistently pulsed at a 1.106-second interval". These were said to be consistent with the flight recorder ULB.[137] but the frequency of the detections was well outside the manufacturer's specification of 37.5 +/- 1.[140] The later signals were at a frequency of 27 kHz, which raised doubts that they were from a black box.[141] On 10 April, a signal recorded by one of the sonobuoys deployed with a hydrophone at 300 metres depth[142][143] was found unlikely to have originated from Flight 370.[144]

Seafloor sonar survey

[edit]On 14 April, due to the likelihood of the ULBs' acoustic pulses having ceased because their batteries would have run down, the Towed Pinger Locator search gave way to a seabed search using side-scan sonar installed in a Bluefin-21 Autonomous Underwater Vehicle.[145] The first day's search was aborted because the sea bed was considerably deeper than the maximum operating depth of Bluefin. Scanning subsequently resumed[146] and after covering 42 square miles in its first four dives, the submersible was reprogrammed to allow it to dive 604 feet lower than its operational limit of 14,800 feet, when the risk of damage was assessed as "acceptable".[147]

Bluefin-21 required 16 missions to complete its search of the 314 square kilometre area around the detections made by the Towed Pinger Locator.[148][149] The seafloor sonar search was suspended on 2 May for the ADV Ocean Shield to return to port to replenish supplies and personnel.[150] Within two hours of its first deployment after returning to the search area on 13 May, Bluefin-21 developed a communications problem and was recovered.[151] Spare parts from the UK were required and the ADV Ocean Shield returned to port to collect the parts.[152][153] After Bluefin-21 was repaired, the seafloor sonar survey resumed on 22 May.[154][155]

The seafloor sonar survey was completed on 28 May. After 30 deployments of the Bluefin-21 to depths of 3,000–5,000 m (9,800–16,400 ft), which scanned 860 km2 (330 sq mi) of seabed, no objects associated with Flight 370 were found. The following day, after analysis of data from the last mission, the ATSB announced the search in the vicinity of the acoustic detections was complete and the area could be discounted as the final location of Flight 370.[156][157] The announcement followed a statement by U.S. Navy's Deputy Director of Ocean Engineering that all four pings were no longer believed to have come from the aircraft's flight recorders.[158] Truss informed parliament that, beginning in August, after a new commercial operator for the search effort had been selected, the search would move into a new phase "that could take twelve months".[159] Equipment envisaged to be used would include towed side-scan sonar.[160]

Bathymetric survey (May–December 2014)

[edit]

During a tripartite meeting with officials from Australia, Malaysia, and China on 5 May, Australian Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss announced that a "detailed oceanographic mapping of the search area"[161] would be conducted to "be able to undertake [the next phase of the] search effectively and safely".[161] It was necessary both for planning the next phase of the search and because equipment used for the next phase would need to operate close to the seafloor (about 100 m or 300 ft).[162] The bathymetric survey was made at a resolution of 100 metres (330 ft) per pixel, which is substantially higher than previous measurements of the seafloor in this area made by satellites and a few passing ships which had their sonar turned on.[163][164]

The Chinese survey vessel Zhu Kezhen departed Fremantle on 21 May to begin the bathymetric survey.[155] On 10 June, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) signed a contract with the Dutch deep sea survey company Fugro to conduct a bathymetric survey of the seafloor in a new search area southwest of Australia.[165] Fugro deployed their vessel MV Fugro Equator, which began bathymetric survey operations on 18 June.[166] The Zhu Kezhen ended survey operations on 20 September and began its return passage to China.[167] The bathymetric survey charted around 208,000 square kilometres (80,000 sq mi) of seafloor through 17 December, when it was suspended for Fugro Equator to be mobilised in the underwater search.[168]

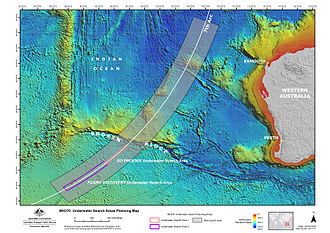

Underwater search (October 2014 – January 2017)

[edit]On 26 June, plans for the next phase of the search were formally announced; the search zone for the new phase was shifted to a new region of up to 60,000 square kilometres (23,000 sq mi) near Broken Ridge in the southern Indian Ocean based on a report released the same day by the ATSB, which detailed the methodology for determining the search area.[169] The search was expected to begin in August and after the bathymetric survey was complete,[170] but it was delayed until October with only part of the survey completed.[171]

Malaysia announced in July that they had contracted with state-run oil company Petronas to supply a team to participate in the search. Petronas, in turn, had contracted the vessel GO Phoenix—owned by Australian company GO Marine Group—and the marine exploration firm Phoenix International, who would supply experts and equipment.[172][173] Phoenix had recovered black boxes from several undersea aircraft wrecks: Air France Flight 447, Yemenia Flight 626, Adam Air Flight 574, and Tuninter Flight 1153. Phoenix planned to use the SLH ProSAS-60 towed synthetic aperture side scan sonar system (rated to 6,000 m depth) to produce a high-resolution image of the ocean floor.[174] On 6 August, Australia, Malaysia, and China jointly announced that Fugro had been awarded a contract to conduct this latest phase of the search.[173][175]

The underwater search began on 6 October with the vessel GO Phoenix, which departed Jakarta on 24 September and calibrated its instruments before arriving in the search zone on 5 October.[171] Based on further analysis of Flight 370's satellite communications,[176] detailed in an ATSB report published 8 October, the priority search area for the underwater search was shifted south from the area identified in June.[177][178] On 18 October, Fugro Discovery departed Perth to join the search.[179] The two vessels were joined by Fugro Equator and Fugro Supporter in January 2015.[180][181][182]

On 16 April 2015, a tripartite meeting between Malaysian, Australian and Chinese officials was held. Over 60 percent of the 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi)[183] priority search area had been searched and, excluding significant delays, the search of the priority search area was expected to be mostly complete by the end of May.[184] The countries agreed that if no trace of the aircraft was found in the priority search area, the underwater search would be extended to an additional 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi) of adjacent seafloor.[183][185][186]

In early May, Fugro Supporter withdrew from the underwater search and offloaded its AUV in Fremantle. Sea conditions during the austral winter are too rough to safely launch and recover an AUV and therefore, AUV operations would be suspended during the winter months. However, the AUV would be kept ready to assist the search at short notice.[187] On 20 June, GO Phoenix left the search area to begin passage to Singapore, where it would be demobilized from search activities.[188][needs update]

On 17 January 2017, the MV Fugro Equator left the search area after the search of the entire 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) underwater search area was completed. The same day, a joint communiqué was issued by the JACC announcing that the search for Flight 370 was suspended.[189][190] The suspension of the search was in accord with a July 2016 agreement between Australia, Malaysia, and China that the search would be suspended, not ended, upon the completion of the search of the 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) search area if it yielded no evidence of Flight 370 and there was an "absence of credible new evidence leading to the identification of a specific location of the aircraft."[191]

Methodology

[edit]

Examination of possible end-of-flight scenarios indicate the aircraft may be located relatively close to the seventh BTO arc. On account of this, the underwater search began at the seventh BTO arc and has progressed outwards.[176]: 12 Towed underwater vehicles equipped with synthetic aperture sonar, side-scan sonar, and multi-beam echo sounders are towed close to the seafloor to create a three-dimensional picture of the seafloor topography.[192]

The sonar data was analysed on board the search vessels at the time of acquisition by sonar analysts and a representative of the ATSB. Data from Fugro vessels was transmitted by satellite to a team of Fugro sonar specialists and geophysicists in Perth then transmitted to the ATSB. Data from the ProSAS sonar used by the GO Phoenix and Dong Hai Jiu 101 was analysed onboard and transmitted to the ATSB during port calls in Perth. In both cases, data was further reviewed by ATSB staff in Canberra and both a quality assurance review and independent expert review were performed by experts in the United States. At all stages, the data was analysed for quality, coverage, and contacts (areas of interest).[193]: 11 Contacts were classified into three levels:[3]

- Category 3: Areas that stand out from their surroundings and are of some interest, but are unlikely to be significant to the search.

- Category 2: Areas of comparatively more interest, but still unlikely to be significant to the search. Some of these are possibly manmade objects, such as objects with the dimensions of shipping containers.

- Category 1: Areas of high interest to the search, requiring prompt investigation.

- Side scan sonar, category 1 contact

- Synthetic aperture sonar, category 2 contact

- Side scan sonar, category 3 contact

- Synthetic aperture sonar, category 3 contact (possibly shipping containers)[3]

Through 20 December 2016, 605 Category 3, 39 Category 2, and two Category 1 contacts were identified. The two Category 1 contacts were identified as a shipwreck and a rock field.[193]: 11 The shipwreck was later identified as a merchant ship West Ridge that was lost in 1883.[194]

Underwater search assets

[edit]

- MV Fugro Discovery initially carried an EdgeTech DT-1 towfish, named Dragon Prince,[192] which was replaced with a new towfish, named Intrepid, in April 2015.[195] The vessel joined the underwater search on 23 October 2014.[167]

- MV Fugro Equator was scheduled to join the search in late October 2014,[167] but resumed bathymetric survey work from 19 November to 17 December while waiting for equipment to arrive.[196][197] It returned to Fremantle for mobilisation for the underwater search and joined the underwater search on 15 January 2015.[181] The Fugro Equator was the last vessel involved in the underwater search when it departed the search area on 17 January 2017—the day the search was officially suspended.[190][198]

- MV Fugro Supporter participated in the search from late January until early May 2015.[180][182][187]

- MV GO Phoenix carried experts and equipment from Phoenix International.[167] The first vessel to begin underwater search operations, on 6 October 2014.[177] It left the search on 20 June 2015.[188]

- MV Havila Harmony carried an AUV used to search the most rugged terrain. It arrived in the search area on 5 December 2015.[199][200][further explanation needed]

- MTS Dong Hai Jiu 101 was a rescue and salvage tug supplied by the Chinese government. The vessel joined the search in February 2016; it left the search area on 3 December 2016.[201] In September 2016, Australian media pointed out that the Dong Hai Jiu 101 spent few days participating in the search—an estimated 17–30 days between February and September—but spent a significant amount of time anchored in or near the port of Fremantle; the media suggested that the Chinese vessel was likely engaged in espionage—signals intelligence gathering and monitoring of Australian and allied naval traffic—around the port of Fremantle.[202][203] When active in the search, it carried a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) from Fremantle to recover the towfish lost in March and was mobilised from October through December with an ROV to participate in the search.[201][204][205]

MV Fugro Discovery, MV Fugro Equator, and MV GO Phoenix were equipped with towed underwater vehicles (also known as "towfish"), which carry synthetic aperture sonar, side scan sonar, and multi-beam echo sounders. The towfish were towed behind the vessel on cables up to 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) in length. The length of the cable was varied to keep the towfish at an altitude of 100–150 metres (330–490 ft) above the seafloor. The data collected by the instruments was relayed in real-time along the tow cable to the vessel, where it was processed and analysed to see if any debris associated with Flight 370 was present on the seafloor.[192]

The MV Fugro Supporter and MV Havila Harmony were equipped with a Kongsberg HUGIN 4500 autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), which carried the same instruments as the towfish deployed by the other vessels. Unlike the towfish, the AUVs were self-propelled and could manoeuvre themselves to maintain a constant altitude above the seafloor. When launched, the torpedo-shaped AUV dived to the proper altitude, then followed a pre-programmed search pattern for up to 24 hours, collecting sonar data for up to 24 hours; when the mission was complete, the AUV surfaced and was recovered by the vessel, where the data was downloaded and the batteries were swapped for the next mission. The AUVs were used to scan areas which could not be effectively searched by the towfish on the other three vessels.[192][200] Because of the difficulty in operating the AUV during the austral winter months due to sea conditions, the AUV operations were suspended during the austral winter months.[206]

In January 2016, a towfish pulled by the Fugro Discovery collided with an underwater mud volcano despite its use of forward-looking obstacle avoidance sonar.[207][208] The towfish was later recovered by the Havila Harmony and transferred to Fugro Discovery to continue the search.[209] Another towfish was lost on 21 March 2016.[210][further explanation needed]

Shipwreck discoveries

[edit]On 13 May 2015, it was announced that Fugro Equator had discovered wreckage of a previously uncharted 19th century cargo ship 4,000 metres underwater, more than 1,000 km off Australia's west coast.[211][212] Fugro Supporter was diverted to the area to deploy an unmanned submarine to scan the seabed. Imaging of the site clearly showed an anchor and other manmade objects. It was announced that the related imagery would be provided to expert marine archaeologists for potential identification.[213] Peter Foley, director of search operations, called it a "fascinating find but it's not what we're looking for".[214]

In December 2015, an anomalous sonar contact was made of a possible man-made object and the Havila Harmony was sent to investigate. On 2 January 2016, its AUV captured high-resolution sonar images, which confirmed the contact was a shipwreck. Experts at the Western Australian Museum advised that the ship is likely an iron or steel vessel from the turn of the 19th century.[215]

Debris discovered (July 2015 – July 2016)

[edit]

On 29 July 2015, airliner marine debris was found on the coast of Réunion Island in the western Indian Ocean, about 4,000 km (2,500 mi) west of the underwater search area and 5,600 km (3,500 mi) southwest of the aircraft's last primary radar contact.[216][217] The object had a stenciled internal marking "657 BB". The following day, a damaged suitcase, which may have been associated with Flight 370, was found.[218] The location is consistent with models of debris dispersal 16 months after an origin in the current search area, off the coast of Australia.[216][217][219] On 31 July, a Chinese water bottle and an Indonesian cleaning product were found in the same area;[220][221] all such debris received intense scrutiny.[222]

Aviation experts have stated that the piece of debris resembles a wing flaperon from a Boeing 777, noting that the marking "657 BB" is a code for a portion of a right wing flaperon from that aircraft.[223][224] The object was transported from Réunion—an overseas department of France—to Toulouse, for examination by France's civil aviation accident investigation agency, the Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile, and a French defence ministry laboratory.[216] Malaysia sent investigators to both Réunion and Toulouse.[216][225] Furthermore, French police conducted a search of the waters around Réunion for additional debris.[216]

On 5 August, the Malaysian Prime Minister announced that experts have "conclusively confirmed" that the debris found on 29 July was from Flight 370; the debris was the first physical evidence that Flight 370 ended in the Indian Ocean.[226] On 3 September French prosecutors formally announced that the flaperon was certainly from Flight 370, a unique serial number having been formally identified by a technician from Airbus Defence and Space in Spain, which had manufactured the flaperon for Boeing.[227]

Search for additional debris

[edit]A week after the discovery of a flaperon from Flight 370 on a beach on Réunion, France announced plans for an aerial search for possible marine debris around the island. On 7 August 2015, France began searching an area 120 km (75 mi) by 40 km (25 mi) along the east coast of Reunion.[228] Foot patrols for debris along beaches were also planned.[229] Malaysia asked authorities in neighboring states to be on alert for marine debris which could be from an aircraft.[230]

On 23 March 2016, what appeared to be a piece of a Rolls-Royce engine cowling was found on a beach in South Africa. The Malaysian authorities sent a team to recover the piece and determine whether or not it came from the missing plane.[231]

On 24 June 2016, the Australian Transport Minister, Darren Chester, said that a piece of aircraft debris was found on Pemba Island, off the coast of Tanzania. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau announced on 22 June that a piece of debris found on an Australian island earlier in June was not from Flight 370.[232] On 20 July, the Australian government released photos of the piece of debris found on Pemba Island around 24 June, believed to be an outboard wing flap.[233]

Suspension of joint search in 2017

[edit]On 17 January 2017, Malaysia, Australia and China officially announced the suspension of the underwater search, stating that "despite every effort using the best science available, cutting edge technology, as well as modeling and advice from highly skilled professionals who are the best in their field, ... the search has not been able to locate the aircraft".[190][189] The decision to suspend the search was in line with a July 2016 agreement between Australia, Malaysia, and China that the search would end upon completion of the search of the 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) search area unless there was credible evidence leading to a specific area where the flight may have ended.[234][189][235]

The decision to suspend the search came a month after a December 2016 ATSB report concluded that searching an additional 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) area on the northern edge of the 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) search area "would exhaust all prospective areas for the presence of [Flight 370]."[193]: 23 Extending the search to this additional area would have cost an estimated AU$40 million.[236] The support group for family members, Voice370, released a statement expressing their disappointment.[190][236]

2018 Ocean Infinity search

[edit]On 17 October 2017, Malaysia received proposals from three companies (including the Dutch company Fugro and the U.S. salvage company Ocean Infinity) offering to continue the search for the aircraft.[237] Later that month, the Malaysian government released a statement that it was in discussion with Ocean Infinity to make a further underwater search in the area to the north of the 2016 search, on the basis of no fee if the wreckage was not found.[238] The search started on 22 January and ended in June 2018 without finding the aircraft.

Basis of search

[edit]

The proposed additional searching was to be based on the drift modelling work undertaken by the CSIRO in 2016, and presented in the CSIRO Drift Reports 2, 3 and 4 subsequently published by ATSB.[239] The essence of the CSIRO work was to investigate the most likely paths taken by drifting debris originating along the 7th BTO arc search area, and comparing this to recovered debris along the east coast of Africa and neighbouring Indian Ocean islands. Of particular interest was the first main recovered object, the starboard flaperon, which was found on Reunion Island in July 2015.[240]

Early drift analysis, based on data collected over years from hundreds of buoys deployed by the Global Drifter Program of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, worked on the presumption that currents in the southern portion of the Indian Ocean, around 40-50 degrees South latitude, flow to the east accompanied by predominately westerly winds. Currents and winds in the northern portion however, around 20 degrees South, both flow to the west. Between these zones lies an "intermediate" area with no dominant movement either way. The main MH370 underwater search areas, from around 36°S to 40°S, extended across several of these zones, making debris drift prediction uncertain.[240]

Satellite oceanographic data obtained by the CSIRO team revealed that in early March 2014, a ridge of high sea level cut across the main 7th arc search area, producing two prominent westward surface currents in the "intermediate" zone, one at 30°S and one at 35°S. This would have initiated a westerly movement of any floating debris in these areas. This helped address one of the key questions raised by the analysts as to why no debris was being found along the nearby west coast of Australia. This absence, along with the satellite data, strengthened the case for the impact position being further located north than previously calculated, with a latitude around 35°36′S 92°48′E / 35.6°S 92.8°E being the most likely according to the data.[240]

High-resolution satellite images from a number of sources (Pleiades,[241] NOAA SST[242]) indicated a number of possibly man-made floating objects which, when analysed in conjunction with the revised drift analysis, could potentially have all originated in close proximity within the 7th BTO arc. The conclusion of the CSIRO Drift Report 3 was that this location was most likely to be north of the original search area, at around 35°S latitude.[243]

Debris drift testing

[edit]

The recovery of the Boeing 777 flaperon at Reunion Island in July 2015 was unexpected by the prevailing drift analyses, as it appeared to arrive far earlier than was predicted for a crash location within the search area.[244] Physical testing of both replica and real flaperon items was undertaken to try to explain this occurrence.[240]

A genuine 777 flaperon was obtained from the ATSB by the CSIRO and cut down to resemble the recovered item. Buoyancy checks were done to correctly match that of the MH370 debris, and two weeks of fields tests were undertaken in North West Bay and Storm Bay, Tasmania to measure the flaperon's wind and current drift under a range of conditions. This testing revealed several significant pieces of information. Firstly, the flaperon, when cut to the shape of the recovered item, didn't drift exactly in-line with the prevailing wind, but exhibited a leeway drift of around 20° to the left. Secondly, due to the high float attitude of the flaperon, the wind effect was greater than originally expected, resulting in a corresponding overall faster speed of drift. These two data provided concurrence between the July 2015 arrival of the flaperon on Reunion Island, and it having had a source location in the northern end of the original search area.[240]

Calculated most likely location of impact

[edit]

Simulated drift trajectories of a large number of such flaperons were mapped in the analysis, based on them all having a source location within the southern end of the "remaining high probability area" identified in the ATSB First Principles Review (FPR) report.[245] This area extended approximately 25 nautical miles (46 km; 29 mi) each side along the 7th arc from around 32.5°S in the north to around 36°S in the south. The modelled trajectories indicated that a source location of around 35°S was consistent both with the maximum probability that no debris would be found on Western Australia, and good consistency that debris would appear at Reunion Island from July 2015.[240]

The reports concluded that the most likely location of MH370 is within the southern end of the 25,000 square kilometres (9,700 sq mi) area identified in the ATSB FPR, near 35°S.[244]

2018 search resumption

[edit]

In January 2018, Ocean Infinity announced its intention to resume the search in the narrowed 25,000 km2 area. The attempt was approved by the Malaysian government, provided payment will be made only if the wreckage is found.[246][247] Initially, the search was to be focused within the "high-probability" area identified by the ATSB.[248] Under the contract, Ocean Infinity was to be paid up to $70 million, depending on the duration of the search; however, the plane had to be found in 90 days after the start of the search.[249] In March 2018, the Malaysian government clarified that the 90 days limit did not include the necessary breaks for the vessel to resupply, and so the search was to continue until mid-June.[250]

Ocean Infinity chartered the Norwegian multi-purpose offshore vessel Seabed Constructor to conduct the search. Maritime assets deployed by Ocean Infinity for the search include up to eight autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), each able to operate independently within a group, at depths down to 6,000 metres (20,000 ft) without physical tethering to a surface vessel. The AUVs were to be equipped with a range of scanning technologies including side-scan sonar, multi-beam echo sounder, bottom profiler, high-definition camera, environmental sensors, magnetometer and synthetic aperature sonar.[248][251][252]

The vessel arrived at the search area on 21 January 2018 and started the search on 22 January 2018. The planned search area of site 1, where the search begun, was 33,012 square kilometres (12,746 sq mi), while the extended area covered some more 48,500 square kilometres (18,700 sq mi).[253] During the search, operations were temporarily suspended three times, while Seabed Constructor transited to Fremantle for refuelling, resupply, and crew change (twice); each transition took some ten days.[254][255][256][257][258][259] In March 2018, Seabed Constructor started to search small areas beyond the originally planned search area.[260] In April 2018, all areas of site 1 has been searched. The search continued northeast,[260][261] and later that month area further northeast along the 7th arc (Site 4) was added to the search plan.[262] In May 2018, the total area covered during the search exceeded 81,500 square kilometres (31,500 sq mi), roughly the originally planned area of site 1 together with the extended area.[259] The total area searched was some 120,000 square kilometres (46,000 sq mi).[263]

According to Loke Siew Fook, Malaysia's new transport minister, the search was to end 29 May 2018.[264] As of 1 June 2018, the search was reported as ongoing, searching beyond site 4 in the area where in 2014 MV Haixun 01, operated by the China Maritime Safety Administration, had detected an acoustic signal[265] suspected to originate from an underwater location beacon attached to the plane's black boxes. However, while several detections had been made, none could have been detected when the ship had passed the same location on an opposing heading, and independent analyses of the detections had determined that the signals had not match the performance standards of the underwater location beacons. It had been considered possible but unlikely that the signals could have had originated from a damaged one.[16]: 13 The spokesperson for Ocean Infinity confirmed the contract with the Malaysian government had ended and the search itself would end soon,[266] probably on 8 June 2018.[267]

On 9 June 2018, it was reported that the search had ended unsuccessfully.[268] Ocean floor mapping data collected during the search were donated to the Nippon Foundation GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project to be incorporated into the global map of the ocean floor.[269][263]

Possible further search

[edit]In March 2019, in the wake of the 5th anniversary of the disappearance, the Malaysian government stated it was willing to look at any "credible leads or specific proposals" regarding a new search.[270][271] Ocean Infinity stated they are ready to resume the search on the same no-fee no-find basis, believing they would benefit from the experience they gained from their search for the wreck of Argentinian submarine ARA San Juan and bulk carrier ship Stellar Daisy, with the most probable location still being somewhere along the 7th arc around the area identified previously, the one on which their 2018 search was based.[272] In March 2022, Ocean Infinity committed to resuming its search in 2023 or 2024, pending approval by the Malaysian government, with two new robotic ships to replace Seabed Constructor.[9]

On 8 March 2023, the ninth anniversary of the disappearance of flight MH370, Malaysian Transport Minister Anthony Loke vowed not to "close the book" on MH370, adding that due consideration would be given to future searches if there was "new and credible information" on the aircraft's potential location.[273] In March 2024, days before the tenth anniversary of the disappearance, Malaysia said it would consult with Australia about collaborating on another expedition by the Ocean Infinity team.[274][275][276] In March 2024, the University of Liverpool highlighted that researchers have embarked on studies of the impact of aircraft on Weak Signal Radio Communication (WSPR). Some investigators have explored the use of WSPR statistical data to estimate the final flight path of MH370 along the 7th arc.[277]

On 20 December 2024, the Malaysian government agreed "in principle" to a new search effort conducted by Ocean Infinity.[278]

Analysis of hydroacoustic data

[edit]A source of evidence to assist in locating the final resting place of the aircraft is analysis of underwater sound recordings. If the aircraft hit the ocean hard enough, hydroacoustic recordings could have potentially recorded an impact event. Furthermore, the aircraft's flight data recorders were fitted with underwater "pingers", which emit a detectable, pulsating acoustic signal that could have potentially led searchers to their locations.

Impact event

[edit]If Flight 370 had impacted the ocean hard, resulting underwater sounds could have been detected by hydrophones, given favourable circumstances.[16]: 40 [279][280] Sound waves can travel long distances in the ocean, but sounds that travel best are those that are reflected into the 'deep sound channel' usually found between 600 and 1,200 m beneath the surface. Most of the sound generated by an aircraft impacting the ocean would travel straight down to the seabed, making it unlikely that any of these sounds would be reflected into the deep sound channel unless the seabed sloped. Sounds from pieces of the aircraft imploding at depth would be more likely to travel in the deep sound channel. "The combination of circumstances necessary to allow [detection of an ocean impact] would have to be very particular", according to Mark Prior, a seismic-acoustic specialist at the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), who also explains that "given the continuing uncertainty regarding the fate of MH370, underwater acoustic data still has the possibility of adding something to the search."[280] When an Airbus A330 hit the Atlantic Ocean at speed of 152 kn (282 km/h; 175 mph), no data relating to the impact was detected in hydroacoustic recordings, even when analysed after the location of that aircraft was known.[280][281] As with the analysis of the Inmarsat satellite data, the hydroacoustic analysis uses the data in a way very different from that originally intended.[281]

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau requested the Curtin University Centre for Marine Science and Technology (CMST) analyse these signals.[16]: 40 Scientists from CTBTO and Geoscience Australia have also been involved with the analysis. Available sources of hydroacoustic data were:[16]: 40, 47 [279][280][281]

- The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), which operates a system of sensors to detect nuclear tests to ensure compliance with the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Data was analysed from CTBTO hydrophones located south-west of Cape Leeuwin, Western Australia (HA01) and in the northern Indian Ocean. These stations have two hydrophones each, separated by several kilometres, allowing a bearing to be calculated for the source of noise to within 0.5°.

- Australia's Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS).[282] Data from an acoustic observatory (RCS) 40 km west of Rottnest Island, Western Australia, near the Perth Canyon. IMOS stations have just one hydrophone each and therefore cannot provide a bearing on the source of the noise. Several IMOS recorders deployed in the Indian Ocean off northwestern Australia by CMST may have recorded data related to Flight 370. As of 2014, these recorders were not recovered as part of the investigation. These sensors record only five minutes out of every fifteen and are likely to be contaminated by noise from seismic surveys.

- It is unclear what other sources of hydroacoustic data are available in the region. India and Pakistan operate submarine fleets, but the JACC claims they are not aware of any hydrophones operated by those countries. The U.S. Navy operated a vast array of hydrophones—the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS)—during the Cold War to track submarines, which is believed to remain in operation. Asked if any SOSUS sensors are located in the Indian Ocean, a spokesman for the U.S. Navy declined to comment on the subject, noting that such information is classified.

Scientists from the CTBTO analysed their recordings soon after Flight 370 disappeared, finding nothing of interest. However, after the search for the flight shifted to the Indian Ocean, CMST collected recordings from the IMOS and found a clear acoustic signature just after 01:30 UTC on 8 March.[279] This signature was also found, but difficult to discern from background noise, in the CTBTO recordings from HA01, likely because HA01 receives a lot of noise from the Southern Ocean and Antarctic coastline.[279]

The CMST researchers believe that the most likely explanation of the hydroacoustic data is that they come from the same event, but unrelated to Flight 370.[16]: 47 They note that "the characteristics of the [event's acoustic signals] are not unusual, it is only their arrival time and to some extent the direction from which they came that make them of interest".[16]: 47 If the data relates to the same event, related to Flight 370, but the arc derived from analysis of the aircraft's satellite transmission is incorrect, then the most likely place to look for the aircraft would be along a line from HA01 at a bearing of 301.6° until that line reaches the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge (approximately 2.3°S, 73.7°E). In the latter possibility, if the acoustic recordings are from the impact of the aircraft with the ocean, they likely came from a location where water is less than 2,000 m deep and the seabed slopes downwards towards the east or southeast; if they came from debris imploding at depth, the source location along this line is much less certain.[16]: 47 The lead CMST researcher believed the chance the acoustic event was related to Flight 370 to be very slim, perhaps as low as 10%.[283] The audio recording of the suspect detection was publicly released on 4 June 2014;[279][281] the ATSB had first referenced these signals in a document posted on its website on 26 May.[281]

Underwater locator beacons

[edit]The aircraft's flight recorders were fitted with Dukane DK100 underwater acoustic beacons—also known as "underwater locator beacons" (ULBs) or "pingers"—which are activated by immersion in salt water and thereafter emit a 10 millisecond pulse every second at a frequency of 37.5±1 kHz. The beacons are limited by battery life, providing a minimum of 30 days and have an estimated maximum life of 40 days, according to their manufacturer. The nominal distance at which these beacons can be detected is 2,000–3,000 metres.[16]: 11 Because the flight recorders to which they are attached could provide valuable information in the investigation, an intense effort was made to detect the beacons' pings before their batteries expired.

HMS Echo made one possible detection on 2 April—the same day the ship joined the search effort. The following day, following tests, the detection was dismissed as an artefact of the ship's sonar system.[16]: 11 [114] On the afternoon of 5 April Perth time, HMS Echo detected a signal lasting approximately 90 seconds. The second detection was made within 2 km from the first detection.[284]

MV Haixun 01, operated by the China Maritime Safety Administration, detected a signal at 37.5 kHz pulsing once per second on 4 April and again on 5 April at a position 3 km west of the first detection.[131] HMS Echo was sent to the location of the MV Haixun 01 detections and determined that the detections were unlikely to originate from ULBs attached to the plane's black boxes due to the depth of the seafloor, surface noise, and the equipment used. A submarine sent to the location made no acoustic detections.[16]: 13

ADV Ocean Shield was sent to the search area with two Phoenix International TPL-25 towed pinger locators (also known as "towfish"). Shortly after one of the towfish was deployed, while descending, an acoustic signal was detected at a frequency of 33 kHz on 5 April. Further detections were made on 5 April and on 8 April, but none could be detected when the ship passed the same location on an opposing heading.[16]: 12

Independent analyses of the detections made by ADV Ocean Shield determined that the signals did not match the performance standards of the ULBs attached to the aircraft's black boxes. However, although unlikely, they noted that the signals could have originated from a damaged ULB.[16]: 13

Between 6–16 April, AP-3C Orion aircraft of the Royal Australian Air Force deployed sonobuoys, which sank to a depth of 300m to detect the acoustic signature of the ULBs attached to the aircraft's black boxes. Sonobuoy drops were carried out at locations along the calculated arc of the final satellite communication with Flight 370 where seafloor depths were considered favourable, near the MV Haixun 01 detections, and along the bearing determined by the Curtin University research team of a possible impact event. One AP-3C Orion sortie was capable of searching an area of 3,000 square kilometres (1,200 sq mi). No acoustic detections related to the ULBs attached to the aircraft's black boxes were made by the sonobuoys.[16]: 13

The interim report released by the Malaysian Ministry of Transport in March 2015 mentioned, for the first time publicly, that the battery for the ULB attached to the flight data recorder had expired in December 2012. The battery's (and thus the ULB's) performance may have been compromised, but this likely was not significant in the search, given the close range at which the detection must be made and the vast search area.[285][286]

Cost estimates

[edit]The search for Flight 370 is the most expensive search operation in aviation history.[287][288][289][290] In June 2014 Time estimated that the total search effort to that point had cost approximately US$70 million.[291] Malaysia's Ministry of Transport revealed that it had spent RM 280.5 million (US$70 million) on the search through February 2016.[292] The tender for the underwater search was AU$52 million (US$43 million or €35 million)—shared by Australia and Malaysia—for 12 months.[293]

On 17 January 2017, the official search for Flight 370 was suspended after yielding no evidence of the aircraft apart from some marine debris on the coast of Africa.[294] Reported costs of the search varied between US$135–160 million.[295][296][297][298] In February 2017, Malaysia's Transport Minister stated the cost as RM 500 million (US$112.47 million).[299]

Contribution to geophysics and oceanography

[edit]The seafloor sonar data obtained during the underwater search for Flight 370 gives scientists an unusually-large section of deep-ocean seafloor mapped at high resolution; most seafloor bathymetric data at such high resolution covers either a small area or shallower seafloor on continental shelves.[300][301] Previous maps of the seafloor in the region of the underwater search were at a spatial resolution of 1 pixel per 5 km (3.1 mi).[302] The bathymetric survey had a spatial resolution of 40–110 m (130–360 ft).[301] During the October 2014–January 2017 underwater search, the spatial resolution of the side scan sonar used by the towfish varied, but was sufficient to detect a 2-cubic-metre (71 cu ft) object,[b] while the spatial resolution of the synthetic aperture sonar used by the ProSAS deep tow vehicle aboard the GO Phoenix and Dong Hai Jiu 101 had a resolution of 10 cm (3.9 in).[193]: 8–10 By comparison, topographic maps of the Moon, Mars, and Venus have been conducted at 100 m (330 ft) resolution and the most remote land areas on Earth have been mapped at 50 m (160 ft) resolution.[302]

Data from the bathymetric survey revealed numerous subsea volcanoes and evidence of large submarine landslides with slide scarps—cliff faces at the top of the origin of the landslide—up to 180 m (590 ft) high and 10 km (6.2 mi) wide and debris fans more than 150 km (93 mi) long.[302][301] Data from the bathymetric survey and underwater search may be used for oil, gas, and mineral exploration. Two features within the search area—Broken Ridge and the Kerguelen Plateau—potentially contain oil and gas deposits, while a field of manganese nodules—which also contain iron ore, nickel, copper, and cobalt—on the seafloor could also be exploited.[303] Geoscience Australia published some of the underwater survey data in March 2017[300] with a high resolution dataset hosted at NCI Australia.[304]

See also

[edit]- Air France Flight 447 – Crashed into the Atlantic Ocean in 2009. After several extensive searches, the fuselage and flight recorders were discovered two years later.

- Flying Tiger Line Flight 739 – Disappeared over the Pacific Ocean in 1962. Despite one of the largest ever search and rescue operations, the aircraft was never found.

- South African Airways Flight 295 – Crashed into the Indian Ocean in 1987. The search and recovery process took more than two years and was the deepest underwater search and recovery at the time.

- Varig Flight 967, a flight from 1979 that crashed over the Pacific Ocean with its wreckage still not found.

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

Notes

[edit]- ^ The flight is also known as Flight MH370 or MAS370. MH is the IATA designator for Malaysia Airlines and the combination of the ICAO designator and flight number is a common abbreviated reference for a flight.[1]

- ^ The ATSB established that the search equipment would need to detect an object 1 m × 1 m × 2 m (3.3 ft × 3.3 ft × 6.6 ft)—a conservative estimate of the size of a Boeing 777 engine without cowlings.[193]: 7

References

[edit]- ^ "Airline Codes – IATA Designators". Dauntless Jaunter. Pardeaplex Media. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (22 July 2016). "MH370 Search To Be 'Suspended' If Plane Isn't Found In Current Search Area". NPR. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "MH370 Operational Search Update – 5 March 2015". JACC. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "MH370: aircraft debris found on Réunion Island 'from Boeing 777'". The Guardian. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "MH370 Search: Too Early to Tell Whether Debris on Réunion Island is Part of Missing Jet". CBC News. Canada: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ "MH370: Debris found on Réunion Island belongs to missing airliner". CBC News. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ ATSB. "MH370 – First Principles Review" (PDF). www.atsb.gov.au. Australian Transport Safety Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ "MH370: Search suspended but future hunt for missing plane not ruled out". BBC News. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ a b Thomas, Geoffrey (6 March 2022). "Ocean Infinity commits to new search for MH370 in 2023 or 2024". Airline Ratings. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Shahabudin, Shahrul (4 May 2024). "Ocean Infinity proposes November start for MH370 search". Ocean Infinity proposes November start for MH370 search. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ "MH370 search to restart based on 'credible' proposal, says Malaysia". The Independent. 6 November 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ Ewe, Koh (20 December 2024). "MH370: Malaysia agrees to resume search for missing passenger jet". BBC Home. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Tweet". Twitter. Flightradar24. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia Airlines 2Q loss widens. Restructuring is imminent but outlook remains bleak". CAPA Centre For Aviation. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

The only significant cut MAS implemented in 2Q2014 was on the Beijing route, which is now served with one daily flight. (MH370 was one of two daily flights MAS had operated to Beijing.)

- ^ a b c d Malaysia Ministry of Transport (8 March 2014). "Factual Information, Safety Investigation: Malaysia Airlines MH370 Boeing 777-200ER (9M-MRO)" (PDF). Malaysia Ministry of Transport. Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "MH 370 – Definition of Underwater Search Areas" (PDF). Australian Transport Safety Bureau. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ a b "MH370: cockpit transcript in full". The Guardian. 1 April 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ a b "MH370 Flight Incident". Malaysia Airlines. 8–17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "No MH370 Distress Call, Search Area Widened". Aviation Week & Space Technology. 12 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014.

- ^ Broderick, Sean (1 May 2014). "First MH370 Report Details Confusion In Hours After Flight Was Lost". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "Documents: Preliminary report on missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370". CNN. 9 April 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Saturday, March 08, 07:30 AM MYT +0800 Media Statement – MH370 Incident released at 7.24am". Malaysia Airlines. scroll to bottom of page. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Sudworth, John; Pak, Jennifer; Budisatrijo, Alice (9 March 2014). "Missing Malaysia Airlines plane 'may have turned back'" (text, images & videos). BBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Pete Williams, Robert Windrem and Richard Esposito (9 March 2014). "Missing Malaysia Airlines Jet May Have Turned Back: Officials". NBC News. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ Jim Clancy and Mark Morgenstein (9 March 2014). "New leads explored in hunt for missing Malaysia Airlines flight". CNN. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Melissa Chi (9 March 2014). "DCA: Search for MH370 intensifies with 74 vessels, 50 nautical miles near last-known site". The Malay Mail. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ a b Hildebrandt, Amber (10 March 2014). Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370: 'Mystery compounded by mystery'. CBC News.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia plane: What we know" (text, images & video). BBC News. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Malaysia Plane: Iranian Bought Two Tickets". Sky News. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil slick spotted by rescuers 'not from missing Malaysia Airlines flight', tests reveal". South China Morning Post. 10 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ "China Releases Images of What Could be Parts of Missing Plane". Malaysia Sun. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia Airlines Flight 370: Vietnam sees no debris in area flagged by Chinese". CNN. Retrieved 13 March 2014. (coordinates in the CNN video)

- ^ Brummitt, Chris (13 March 2014). "Malaysia: No debris at spot shown on China images". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014.

- ^ "U.S. suspects missing flight flew for hours after last confirmed location, report says". The Washington Post. 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Vast waters hide clues in hunt for missing Malaysia Airlines flight". CNN. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ RMAF chief: Recordings captured from radar indicate flight deviated from original route. The Star, 9 March 2014

- ^ "15 space organizations join hunt for missing Malaysian jet". CNET. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia Airlines jet". International Charter on Space and Major Disasters. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Exclusive: Radar data suggests missing Malaysia plane deliberately flown way off course – sources. Reuters, 12 March 2014

- ^ Head, Jonathan (12 March 2014). "Malaysia Airlines MH370: Confusion over plane last location". BBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "MISSING MH370: Malaysia welcomes SAR assistance from other countries". New Straits Times. 9 March 2014. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Wong, Chun-Han; Vu, Trong Khanh; Raghuvanshi, Gaurav (9 March 2014). "Countries Put Disputes Aside for Airliner Search". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew; Withnall, Adam (10 March 2014). "Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370: Oil slicks in South China Sea 'not from missing jet', officials say". The Independent.

- ^ Franco, Michael (12 March 2014). "15 space organizations join hunt for missing Malaysian jet | Crave". CNET.

- ^ "Disaster Charter – Homepage". Disasterscharter.org. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014.

- ^ "Disaster Charter – Missing Malaysia Airlines jet". Disasterscharter.org. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ "Number of countries in SAR operations increases to 26". The Star. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Bei, Seow (9 April 2014). "MH370: Straits Times Web Special highlights sea and air assets used in hunt". The Straits Times. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Flight MH370: A look at the 26 nations involved in search for missing Malaysia Airlines jet – National". Globalnews.ca. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Maldives island residents see 'low flying jumbo jet'". 23 April 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Too early to come to any conclusion, says Najib". Daily Express. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Vietnam, Malaysia mount search for plane". Sky News Australia. 8 March 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia widens area of search for missing MAS aircraft". Borneo Post. Bernama. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Missing MAS flight: Malaysia grateful for assistance in search and rescue operations, says Anifah". The Star. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Boeing 777-200 – Flight MH 370 – Malaysia Airlines". BEA. 24 March 2014. Archived from the original (text) on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Missing Malaysian Plane: Royal Navy Submarine HMS Tireless Arrives In Indian Ocean To Help Search". Huffington Post. 1 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "IDC infrasound search for missing flight Malaysian Airlines MH370" (PDF). CTBTO Prep Com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ Paul Marks (11 March 2014), Malaysian plane sent out engine data before vanishing New Scientist.

- ^ "Malaysia Airlines MH370: Plane 'changed course'" (text, images & videos). BBC News. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia Airlines live: military denies report they tracked plane hundreds of miles off course". The Daily Telegraph. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

- ^ Danubrata, Eveline; Koswanage, Niluksi (11 March 2014). "Malaysia military tracked missing plane to west coast: source". Reuters. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "MISSING MH370: RMAF chief denies military radar report". New Straits Times. 12 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia Airlines plane: Air force chief denies tracking jet to Strait of Malacca". The Straits Times. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Vietnam says it told Malaysia that missing plane MH370 had turned back". The Straits Times. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Matthew Wald (13 March 2014), U.S. Takes Back Seat in Malaysian Jet Inquiry The New York Times

- ^ a b Orr, Bob (13 March 2014). "Did Malaysian plane fly toward Indian Ocean after last contact?". CBS News. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ Michael Forsythe and Michael S. Schmidt (14 March 2014), Sharp Changes in Altitude and Course After Jet Lost Contact The New York Times.

- ^ Peters, Chris (13 March 2014). "U.S. investigators suspect missing Malaysian plane flew for hours -WSJ". Reuters. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Flight MH370: Australia spots possible plane debris in sea". The Week. UK. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Malaysia says no evidence missing plane flew hours after losing contact". Reuters. 13 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Andy Pasztor (12 March 2014), Missing Airplane Flew On for Hours The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Inmarsat statement on Malaysia Airlines flight MH370". Inmarsat. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Chris Buckley and Nicola Clark (14 March 2014), "Satellite Firm Says Its Data From Jet Could Offer Location". The New York Times.

- ^ Rivera, Gloria; Margolin, Josh; Thomas, Pierre; Good, Dan (15 March 2014). "'Deliberate Act' Used to Steer Missing Plane Off Course" (text, images & video). ABC News. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 deliberately flown off course, systems switched off: PM" (text, images & video). ABC News. 15 March 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ Shazwan, Mustafa Kamal (15 March 2014). "MH370 possibly in one of two 'corridors', says PM". The Malay Mail. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ *"China: no evidence MH370 entered airspace". CNTV English. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

*"Missing Malaysian plane MH 370 never entered Thai airspace". The Indian Express. 18 March 2014.

*G Surach (16 March 2014). "Missing MH370: No way plane flew over Indian airspace undetected – Nation". The Star. Malaysia.

*"Missing Malaysian jet LIVE updates: Kazakhstan says detected no unidentified planes when Malaysian jetliner vanished: Asia, News". India Today. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

*Haris Hussain and Farrah Naz Karim (18 March 2014). "MISSING MH370: EXCLUSIVE: Flying as low as 80 feet 'possible'". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. - ^ McLaughlin, Chris (20 March 2014). "Inmarsat breaks silence on probe into missing jet". Fox News (Interview). Interviewed by Megyn Kelly. 5:00–6:30.

- ^ "Australian bases could be withholding MH370 data - 9News". www.9news.com.au. 19 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

Canberra is reportedly unwilling to disclose whether its RAAF radar was tracking the Boeing 777 as it flew. The over-the-horizon radar is capable of tracking flights as far away as 3000km from Pine Gap, enough to track the aircraft as it flew across the South China Sea… Australian Defence Department said it would not be providing comment on the surveillance system… Pine Gap's primary function is to control US spy satellites, but no information from the base has been shared with the Malaysian government.

- ^ Murdoch, Lindsay (19 March 2014). "Missing Malaysia Airlines plane: plea to US to release Pine Gap data". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

Kuala Lumpur: Malaysia believes data from US spy satellites monitored in Australia could help find missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 but the information is being withheld. The country's Defence Minister Hishammuddin Hussein has specifically asked the US to share information obtained from the Pine Gap base near Alice Springs, according to the government-controlled New Straits Times newspaper.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia Airline plane wreckage not in identified area". Malaysia Sun. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Missing MH370: Australia to lead southern search for MH370". The Star. 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Australia agrees to lead search in Indian Ocean for missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH370". The Canberra Times. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia Airlines MH370: AMSA to coordinate new search 3,000 kilometres south-west of Perth" (text & images). ABC News. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ Jacobs, Frank (26 March 2014). "MH370 and the Secrets of the Deep, Dark Southern Indian Ocean". Foreign Policy

- ^ "AMSA_MH370_MediaKit " 18/03/2014 – AMSA Search Area Charts". Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Search operation for Malaysian airlines aircraft: Update 2" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Search operation for Malaysia Airlines aircraft: Update 4" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 19 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Incident 2014/1475 search for Malaysian airlines flight MH370 planned search area 19 March 2014" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 19 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2015.

- ^ "Search operation for Malaysian airlines aircraft: Update 7" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia Airlines plane: Debris found in search for MH370, says Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ "Missing plane: Objects spotted in water". The New Zealand Herald. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ "Possible Parts of Missing Jet Spotted Off Australia: Prime Minister". NBC News. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.