Second Nagorno-Karabakh War

| Second Nagorno-Karabakh War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict | |||||||||

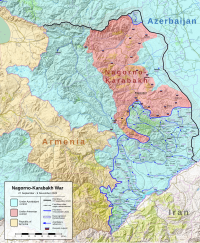

Areas captured by Azerbaijan during the war Areas ceded to Azerbaijan under the ceasefire agreement | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| | | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Azerbaijan

Syrian mercenaries[31] | Artsakh | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Equipment:

|

Equipment:

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Per Azerbaijan:

Per SOHR: See Casualties for details | Per Armenia/Artsakh:

See Casualties and Prisoners of war for details | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War was an armed conflict in 2020 that took place in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding occupied territories. It was a major escalation of an unresolved conflict over the region, involving Azerbaijan, Armenia and the self-declared Armenian breakaway state of Artsakh.[d] The war lasted for 44 days and resulted in Azerbaijani victory, with the defeat igniting anti-government protests in Armenia. Post-war skirmishes continued in the region, including substantial clashes in 2022.

Fighting began on the morning of 27 September, with an Azerbaijani offensive[75][76] along the line of contact established in the aftermath of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988–1994). Clashes were particularly intense in the less mountainous districts of southern Nagorno-Karabakh.[77] Turkey provided military support to Azerbaijan.[75][78]

The war was marked by the deployment of drones, sensors, long-range heavy artillery[79] and missile strikes, as well as by state propaganda and the use of official social media accounts in online information warfare.[80] In particular, Azerbaijan's widespread use of drones was seen as crucial in determining the conflict's outcome.[81] Numerous countries and the United Nations strongly condemned the fighting and called on both sides to de-escalate tensions and resume meaningful negotiations.[82] Three ceasefires brokered by Russia, France, and the United States failed to stop the conflict.[83]

Following the capture of Shusha, the second-largest city in Nagorno-Karabakh, a ceasefire agreement was signed, ending all hostilities in the area from 10 November 2020.[84][85][86] The agreement resulted in a major shift regarding the control of the territories in Nagorno-Karabakh and the areas surrounding it. Approximately 2,000 Russian soldiers were deployed as peacekeeping forces along the Lachin corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, with a mandate of at least five years.[10] Following the end of the war, an unconfirmed number of Armenian prisoners of war were held captive in Azerbaijan, with reports of mistreatment and charges filed against them,[87][88][89][90] leading to a case at the International Court of Justice.[91]

The later 2023 Azerbaijani offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh would see the entirety of the disputed territory come under the control of Azerbaijan.

Naming

The war has been referred to as the "Second Nagorno-Karabakh War",[92][93] and has also been called the "44-Day War" in both Armenia and Azerbaijan.[94][95]

In Armenia and Artsakh, it has been called the "Second Artsakh War" (Armenian: Արցախյան երկրորդ պատերազմ, romanized: Arts'akhyan yerkrord paterazm),[96][97] "Patriotic War"[98] and the "Fight for Survival" (Armenian: Գոյամարտ, romanized: Goyamart).[99]

In Azerbaijan, it has been called the "Second Karabakh War" (Azerbaijani: İkinci Qarabağ müharibəsi)[100] and "Patriotic War".[101][102] The Azerbaijani government referred to it as an "operation for peace enforcement"[103] and "counter-offensive operation".[104] It later announced it had initiated military operations under the code-name "Operation Iron Fist" (Azerbaijani: Dəmir Yumruq əməliyyatı).[105]

Background

The territorial ownership of Nagorno-Karabakh is fiercely contested between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. The current conflict has its roots in events following World War I and today the region is de jure part of Azerbaijan, although large parts were de facto held by the internationally unrecognised Republic of Artsakh, which is supported by Armenia.[106]

Soviet era

During the Soviet era, the predominantly Armenian-populated region was governed as an autonomous oblast within the Azerbaijan SSR.[107] As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate during the late 1980s the question of Nagorno-Karabakh's status re-emerged, and on 20 February 1988 the parliament of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast passed a resolution requesting transfer of the oblast from the Azerbaijan SSR to the Armenian SSR. Azerbaijan rejected the request several times,[108] and ethnic violence began shortly thereafter with a series of pogroms between 1988 and 1990 against Armenians in Sumgait, Ganja and Baku,[109][110][111][112] and against Azerbaijanis in Gugark and Stepanakert.[113][114][115][116] Following the revocation of Nagorno-Karabakh's autonomous status, an independence referendum was held in the region on 10 December 1991. The referendum was boycotted by the Azerbaijani population, which then constituted around 22.8% of the region's population; 99.8% of participants voted in favour. In early 1992, following the Soviet Union's collapse, the region descended into outright war.[108][dead link]

First Nagorno-Karabakh War

The First Nagorno-Karabakh War resulted in the displacement of approximately 725,000 Azerbaijanis and 300,000–500,000 Armenians from both Azerbaijan and Armenia.[117] The 1994 Bishkek Protocol brought the fighting to an end and resulted in significant Armenian territorial gains: in addition to controlling most of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Republic of Artsakh also occupied the surrounding Azerbaijani-populated districts of Agdam, Jabrayil, Fuzuli, Kalbajar, Qubadli, Lachin and Zangilan.[118] The terms of the Bishkek agreement produced a frozen conflict,[119] and long-standing international mediation attempts to create a peace process were initiated by the OSCE Minsk Group in 1994, with the interrupted Madrid Principles being the most recent iteration prior to the 2020 war.[120][121] The United Nations Security Council adopted four resolutions in 1993 calling for the withdrawal of "occupying forces" from the territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh,[122] and in 2008 the General Assembly adopted a resolution demanding the immediate withdrawal of Armenian occupying forces,[123] although the co-chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group, Russia, France and USA, voted against it.[124]

Frozen conflict

For three decades multiple violations of the ceasefire occurred, the most serious being the four-day 2016 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.[125] Surveys indicated that the inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh did not want to be part of Azerbaijan[126] and in 2020 the Armenian prime minister Nikol Pashinyan announced plans to make Shusha, a city of historical and cultural significance to both Armenians and Azerbaijanis,[109] Artsakh's new capital. In August of the same year the government of Artsakh moved the country's parliament to Shusha, escalating tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan.[127] Further skirmishes occurred on the border between the two countries in July 2020.[125] Thousands of Azerbaijanis rallied for war against Armenia in response, and Turkey voiced its firm support for Azerbaijan.[128] On 29 July 2020, Azerbaijan conducted a series of military exercises that lasted from 29 July to 10 August 2020,[129] followed by further exercises in early September with the involvement of Turkey.[130] Prior to the resumption of hostilities, allegations emerged that Turkey had facilitated the transfer of hundreds of Syrian National Army members from the Hamza Division to Azerbaijan.[131] Baku denied the involvement of foreign fighters.[132]

Course of the war

Overview

The conflict was characterised by the widespread use of combat drones, particularly by Azerbaijan,[133] as well as heavy artillery barrages, rocket attacks and trench warfare.[134] Throughout the campaign, Azerbaijan relied heavily on drone strikes against Armenian/Artsakh forces, inflicting heavy losses upon Armenian tanks, artillery, air defence systems and military personnel, although some Azerbaijani drones were shot down.[135][136] It also featured the deployment of cluster munitions, which are banned by the majority of the international community but not by Armenia or Azerbaijan.[137] Both Armenia[138] and Azerbaijan[139] used cluster munitions against civilian areas outside of the conflict zone.[140] A series of missile attacks on Ganja, Azerbaijan inflicted mass civilian casualties, as did artillery strikes on Stepanakert, Artsakh's capital.[141] Much of Stepanakert's population fled during the course of the fighting.[142] The conflict was accompanied by coordinated attempts to spread misleading content and disinformation via social media and the internet.[143]

The conflict began with an Azerbaijani ground offensive that included armoured formations, supported by artillery and drones, including loitering munitions. Armenian and Artsakh troops were forced back from their first line of defence in Artsakh's southeast and northern regions, but inflicted significant losses on Azerbaijani armoured formations with anti-tank guided missiles and artillery, destroying dozens of vehicles. Azerbaijan made heavy use of drones in strikes against Armenian air defences, taking out 13 short-range surface-to-air missile systems. Azerbaijani forces used drones to systematically isolate and destroy Armenian/Artsakh positions. Reconnaissance drones would locate a military position on the front lines and the placement of reserve forces, after which the position would be shelled along with roads and bridges that could potentially be used by the reserves to reach the position. After the Armenian/Artsakh position had been extensively shelled and cut off from reinforcement, the Azerbaijanis would move in superior forces to overwhelm it. This tactic was repeatedly used to gradually overrun Armenian and Artsakh positions.[144] Azerbaijani troops managed to make limited gains in the south in the first three days of the conflict. For the next three days, both sides largely exchanged fire from fixed positions. In the north, Armenian/Artsakh forces counterattacked, managing to retake some ground. Their largest counterattack took place on the fourth day, but incurred heavy losses when their armour and artillery units were exposed to Azerbaijani attack drones, loitering munitions, and reconnaissance drones spotting for Azerbaijani artillery as they manoeuvred in the open.[23]

Azerbaijan targeted infrastructure throughout Artsakh starting on the first day of the war, including the use of rocket artillery and cluster munitions against Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh, and a missile strike against a bridge in the Lachin Corridor linking Armenia with Artsakh. On the 6th day of the war, Armenia/Artsakh targeted Ganja for the first of four times with ballistic missiles, nominally targeting the military portion of Ganja International Airport but instead hitting residential areas. On the morning of the seventh day, Azerbaijan launched a major offensive. The Azerbaijani Army's First, Second, and Third Army Corps, reinforced by reservists from the Fourth Army Corps, began an advance in the north, making some territorial gains, but the Azerbaijani advance stalled.[23]

Most of the fighting subsequently shifted to the south, in terrain that is relatively flat and underpopulated as compared to the mountainous north. Azerbaijani forces launched offensives toward Jabrayil and Füzuli, managing to break through the multi-layered Armenian/Artsakh defensive lines and recapture a stretch of territory held by Armenian troops as a buffer zone, but the fighting subsequently stalled.[23]

After the shelling of Martuni,[145] Artsakh authorities began mobilising civilians.[146] Just before 04:00 (00:00 UTC) on 10 October 2020, Russia reported that both Armenia and Azerbaijan had agreed on a humanitarian ceasefire after ten hours of talks in Moscow (the Moscow Statement) and announced that both would enter "substantive" talks.[citation needed] After the declared ceasefire, the President of Artsakh admitted Azerbaijan had been able to achieve some success, moving the front deep into Artsakh territory;[147] the Armenian Prime Minister announced that Armenian forces had conducted a "partial retreat".[148]

The ceasefire quickly broke down and the Azerbaijani advance continued. Within days Azerbaijan announced the capture of dozens of villages on the southern front.[149] A second ceasefire attempt midnight 17 October 2020 was also ignored.[150] Azerbaijan announced the capture of Jabrayil on 9 October 2020 and Füzuli on 17 October 2020. Azerbaijani troops also captured the Khoda Afarin Dam and Khodaafarin Bridges. Azerbaijan announced that the border area with Iran was fully secured with the capture of Agbend on 22 October 2020.[151] Azerbaijani forces then turned northwest, advancing towards the Lachin corridor, the sole highway between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, putting it within artillery range. According to Artsakh, a counterattack repelled forward elements of the Azerbaijani force and pushed them back. Armenian/Artsakh resistance had managed to halt the Azerbaijani advance to within 25 kilometres of the Lachin corridor by 26 October 2020. Artsakh troops who had retreated into the mountains and forests began launching small-unit attacks against exposed Azerbaijani infantry and armour, and Armenian forces launched a counteroffensive near the far southwestern border between Armenia and Azerbaijan.[152] On 26 October 2020, a US-brokered ceasefire came into effect, but fighting resumed within minutes.[153][154] Three days later, the Artsakh authorities stated that the Azerbaijani forces were 5 km (3.1 mi) from Shusha.[155] On 8 November 2020, Azerbaijani forces seized Shusha,[156] the second-largest city in Artsakh before the war, located 15 kilometres from Stepanakert, the republic's capital.[157]

Although the amount of territory contested was relatively restricted, the conflict impacted the wider region, in part due to the type of munitions deployed. Shells and rockets landed in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran, although no damage was reported,[158][159] and Iran reported that several unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) had been downed or had crashed within its territory.[160][161][162][163] Georgia stated that two UAVs had crashed in its Kakheti Province.[164]

Ceasefire agreement

On 9 November 2020, in the aftermath of the capture of Shusha, a ceasefire agreement was signed by the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, the Prime Minister of Armenia, Nikol Pashinyan, and the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, ending all hostilities in the zone of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict from 10 November 2020, 00:00 Moscow time.[84][85][86] The President of Artsakh, Arayik Harutyunyan, also agreed to end the hostilities.[169]

Under the terms of the deal, both belligerent parties were to exchange prisoners of war and the bodies of the fallen. Furthermore, Armenian forces were to withdraw from Armenian-occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh by 1 December 2020, while a peacekeeping force, provided by the Russian Ground Forces and led by Lieutenant General Rustam Muradov,[170] of just under 2,000 soldiers would be deployed for a minimum of five years along the line of contact and the Lachin corridor linking Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Additionally, Armenia undertook to "guarantee safety" of transport communication between Azerbaijan's Nakhchivan exclave and mainland Azerbaijan in both directions, while Russia's border troops (under the Federal Security Service) were to "exercise control over the transport communication".[171][172][173]

On 15 December 2020, after several weeks of cease fire, the sides finally exchanged prisoners of war. 44 Armenian and 12 Azeri prisoners were exchanged.[174] It is unclear whether more prisoners remain in captivity on either side.

Territorial changes

At the time of the ceasefire, Azerbaijan had retaken most of the area south of the Lachin corridor. It had also captured one-third of Nagorno-Karabakh, mostly in the south. Under the terms of the ceasefire, Azerbaijan regained control over much of its territory that had been lost to Armenia in the earlier war.[175] In total, Azerbaijan regained control of 73% of the disputed territory, including the territory captured in Nagorno-Karabakh. It was reported that Azerbaijan regained control of 5 cities, 4 towns, 286 villages.[176]

Non-military actions taken by Armenia and Azerbaijan

Since the beginning of the conflict, both Armenia and Azerbaijan declared martial law, limiting the freedom of speech. Meanwhile, a new law came into effect since October 2020 in Armenia, which prohibits negative coverage of the situation at the front.[177] Restrictions have been reported on the work of international journalists in Azerbaijan, with no corresponding restrictions reported in Nagorno-Karabakh.[178]

Armenia

On 28 September 2020, Armenia banned men aged over 18 listed in the mobilisation reserve from leaving the country.[179] The next day, it postponed the trial of former President Robert Kocharyan and other former officials charged in the 2008 post-election unrest case, owing to one of the defendants, the former Defence Minister of Armenia, Seyran Ohanyan, going to Artsakh during the conflict.[180]

On 1 October 2020, the Armenian National Security Service (NSS) stated that it had arrested and charged a former high-ranking Armenian military official with treason on suspicion of spying for Azerbaijan.[181] Three days later, the NSS stated that it had arrested several foreign citizens on suspicion of spying.[182] Protesting Israeli arms sales to Azerbaijan, Armenia recalled its ambassador to Israel.[183]

On 8 October 2020, the Armenian President, Armen Sarkissian, dismissed the director of the NSS.[184] Subsequently, the Armenian government toughened the martial law and prohibited criticising state bodies and "propaganda aimed at disruption of the defense capacity of the country".[185] On the same day, the Armenian MoD cancelled a Novaya Gazeta correspondent's journalistic accreditation, officially for entering Nagorno-Karabakh without accreditation.[186] On 9 October 2020, Armenia tightened its security legislation.[185] On 21 October 2020, the Armenian Cabinet of Ministers temporarily banned the import of Turkish goods, the decision will come into force on 31 December 2020.[187] The following day, the Armenian parliament passed a law to write off the debts of the Armenian servicemen wounded during the clashes and the debts of the families of those killed.[188]

On 27 October 2020, the Armenian president Armen Sarkissian dismissed the head of the counterintelligence department of the National Security Service, Major General Hovhannes Karumyan and the chief of staff of the border troops of the National Security Service Gagik Tevosyan.[189] On 8 November 2020, Sarkissian yet again dismissed the interim head of the National Security Service.[190]

As of 8 November 2020, one Armenian activist was fined by the police for his anti-war post.[191]

Azerbaijan

On 27 September 2020, Azerbaijani authorities restricted internet access shortly after the clashes began,[192] stating it was "in order to prevent large-scale Armenian provocations." The government made a noticeable push to use Twitter, which was the only unblocked platform in the country. Despite the restrictions, some Azerbaijanis still used VPNs to bypass them.[193] The National Assembly of Azerbaijan declared a curfew in Baku, Ganja, Goygol, Yevlakh and a number of districts from midnight on 28 September 2020,[194][195] under the Interior Minister, Vilayet Eyvazov.[196] Azerbaijan Airlines announced that all airports in Azerbaijan would be closed to regular passenger flights until 30 September 2020.[197] The Military Prosecutor's Offices of Fuzuli, Tartar, Karabakh and Ganja began criminal investigations of war and other crimes.[198]

Also on 28 September 2020, the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, issued a decree authorising a partial mobilisation in Azerbaijan.[199] On 8 October 2020, Azerbaijan recalled its ambassador to Greece for consultations, following allegations of Armenians from Greece arriving in Nagorno-Karabakh to fight against Azerbaijan.[200] Three days later, the Azerbaijani State Security Service (SSS) warned against a potential Armenian-backed terror attack.[201]

On 17 October 2020, the Azerbaijani MoFA stated that member of the Russian State Duma from the ruling United Russia, Vitaly Milonov, was declared persona non grata in Azerbaijan for visiting Nagorno-Karabakh without permission from the Azerbaijani government.[202] On 24 October 2020, by recommendation of the Central Bank of Azerbaijan, the member banks of the Azerbaijani Banks' Association unanimously adopted a decision to write off the debts of the military servicemen and civilians who died during the conflict.[203]

On 29 October 2020, the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, issued a decree on the formation of temporary commandant's offices in the areas that the Azerbaijani forces seized control of during the conflict. According to the decree, the commandants will be appointed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but they will have to coordinate with other executive bodies of the government, including Ministry of Defense, the State Border Service, the State Security Service, and ANAMA.[204][205]

Over the course of the war several Azerbaijani activists were brought in for questioning by the State Security Service, due to their anti-war activism.[206][207] On 12 December, a decree by President Aliyev lifted the curfew that had been imposed in September.[208]

Casualties

Casualties were high,[209] officially in the low thousands. According to official figures released by the belligerents, Armenia lost 3,825 troops killed[57] and 187 missing,[58] while Azerbaijan lost 2,906 troops killed, with six missing in action.[37] During the conflict, it was noted that the sides downplayed the number of their own casualties and exaggerated the numbers of enemy casualties and injuries.[210]

Civilians

The Armenian authorities stated that 85 Armenian civilians were killed during the war,[c] while another 21 were missing.[58] According to Azerbaijani sources, the Armenian military has targeted densely populated areas containing civilian structures.[212] As of 9 November 2020, the Prosecutor General's Office of the Republic of Azerbaijan stated that during the war, as a result of reported shelling by Armenian artillery and rocketing, 100 people had been killed, while 416 people had been wounded.[61] Also, during the post-war clashes, the Azerbaijani authorities stated that an Azercell employee was seriously injured during the installation of communication facilities and transmission equipment near Hadrut.[213]

As of 23 October 2020, the Armenian authorities has stated that the conflict had displaced more than half of Nagorno-Karabakh's population or approximately 90,000 people.[73] The International Rescue Committee has also claimed that more than half of the population of Nagorno-Karabakh has been displaced by the conflict.[214] As of 2 November 2020, the Azerbaijani authorities has stated that the conflict had displaced approximately 40,000 people in Azerbaijan.[71]

Seven journalists have been injured.[136][215] On 1 October 2020, two French journalists from Le Monde covering the clashes in Khojavend were injured by Azerbaijani shellfire.[216] A week later, three Russian journalists reporting in Shusha were seriously injured by an Azerbaijani attack.[217][218] On 19 October 2020, according to Azerbaijani sources, an Azerbaijani AzTV journalist received shrapnel wounds from Armenian shellfire in Aghdam District.[215]

Military

Armenian authorities reported the deaths of 3,825 servicemen during the war, while the Azerbaijani authorities stated that more than 5,000 Armenian servicemen were killed, and several times more were wounded as of 28 October 2020.[219] After the war, the former director of the Armenian National Security Service, Artur Vanetsyan, had also stated that some 5,000 Armenians were killed during the war.[220] Also, the Armenian authorities had stated that about 60 Armenian servicemen were captured by Azerbaijan as prisoners of war.[60] The former Head of the Military Control Service of the Armenian MoD, Movses Hakobyan, stated that already on the fifth day of war there were 1,500 deserters from Armenian armed forces, who were kept in Karabakh and not allowed to return to Armenia in order to prevent panic. The press secretary of Armenian prime minister called the accusations absurd and asked the law enforcement agencies to deal with them.[221] Former military commissar of Armenia major-general Levon Stepanyan stated that the number of deserters in Armenian army was over 10,000, and it is not possible to prosecute such a large number of military personnel.[222] During the post-war clashes, the Armenian government stated that 60 servicemen went missing,[223] including several dozen that were captured.[224] and On 27 October 2020, Artsakh authorities stated that its defence minister Jalal Harutyunyan was wounded in action.[225] However, unofficial Azerbaijani military sources alleged that he was killed and released footage apparently showing the assassination from a drone camera.[226]

During the conflict, the government of Azerbaijan did not reveal the number of its military casualties.[227] On 11 January, Azerbaijan stated that 2,853 of its soldiers had been killed during the war, while another 50 went missing.[37] Also, Azerbaijani authorities stated that 11 more Azerbaijani servicemen were killed during the post-war clashes or landmine explosions.[228][229][230] On 23 October 2020, President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, confirmed that Shukur Hamidov who was made National Hero of Azerbaijan in 2016, was killed during the operations in Qubadli District.[231] This was the first military casualty officially confirmed by the government. However, Armenian and Artsakh authorities have claimed 7,630 Azerbaijani soldiers and Syrian mercenaries were killed.[232][233]

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights documented the death of at least 541 Syrian fighters or mercenaries fighting for Azerbaijan.[38] On 14 November 2020, the Observatory reported the death of a commander of the Syrian National Army's Hamza Division.[234]

Infrastructure damage

Civilian areas, including major cities, have been hit, including Azerbaijan's second-largest city, Ganja, and the region's capital, Stepanakert, with many buildings and homes destroyed.[240][241] The Ghazanchetsots Cathedral has also been damaged.[242] Several outlets reported increased cases of COVID-19 in Nagorno-Karabakh, particularly the city of Stepanakert, where the population was forced to live in overcrowded bunkers, due to Azerbaijan artillery and drone strikes conflict.[243][244] There were also reported difficulties in testing and contact tracing during the conflict.[243][244]

The Ghazanchetsots Cathedral in Shusha became damaged as a result of shelling. On 19 October 2020, a strong fire broke out in a cotton plant in Azad Qaraqoyunlu, Tartar District, as a result of the Armenian artillery shelling, with several large hangars of the plant becoming completely burned down.[245] An Armenian-backed Nagorno-Karabakh human rights ombudsman report noted 5,800 private properties and 520 private vehicles destroyed, with damage to 960 items of civilian infrastructure, and industrial and public and objects.[246] On 16 November 2020, the Prosecutor General's Office of the Republic of Azerbaijan reported 3,410 private houses, 512 civilian facilities, and 120 multi-storey residential buildings being damaged throughout the war.[61]

Equipment losses

By 7 October 2020, Azerbaijan reported to have destroyed about 250 tanks and other armoured vehicles; 150 other military vehicles; 11 command and command-observation posts; 270 artillery units and MLRSs, including a BM-27 Uragan; 60 Armenian anti-aircraft systems, including 4 S-300 and 25 9K33 Osas; 18 UAVs and 8 arms depots.[219][247][248][249] destroyed. As of 16 October 2020, the Azerbaijani President stated that the Armenian losses were at US$2 billion.[250] In turn an Azerbaijani helicopter was stated to have been damaged, but its crew had apparently returned it to Azerbaijani-controlled territory without casualties.[251] Later it was reported that on 12 October 2020, Azerbaijan had destroyed one Tochka-U missile launcher. On 14 October 2020, Azerbaijan stated it had further destroyed five T-72 tanks, three BM-21 Grad rocket launchers, one 9K33 Osa missile system, one BMP-2 vehicle, one KS-19 air defence gun, two D-30 howitzers and several Armenian army automobiles.[252] On the same day, Azerbaijan announced the destruction of three R-17 Elbrus tactical ballistic missile launchers that had been targeting Ganja and Mingachevir.[253] BBC reporters confirmed the destruction of at least one tactical ballistic missile launcher in the vicinity of Vardenis, close to the border with Azerbaijan, and posted photo evidence in support of this information.[254] Later American journalist Josh Friedman posted a high quality video of a destroyed Armenian ballistic missile launcher.[255]

Armenian and Artsakh authorities initially reported the downing of four Azerbaijani helicopters and the destruction of ten tanks and IFVs, as well as 15 drones.[256] Later the numbers were revised to 36 tanks and armoured personnel vehicles destroyed, two armoured combat engineering vehicles destroyed and four helicopters and 27 unmanned aerial vehicles downed all within the first day of hostilities.[257] They released footage showing the destruction or damage of five Azerbaijani tanks.[258] Over the course of 2 October, the Artsakh Defence Army said they had destroyed 39 Azerbaijani military vehicles, including a T-90 tank; four SU-25 fighter-bombers; three Mi-24 attack helicopters; and 17 UAVs.[259]

According to Dutch warfare research group Oryx, which documents visually confirmed losses on both sides, Armenia lost 255 tanks (destroyed: 146, damaged: 6, captured: 103), 78 armoured fighting vehicles (destroyed: 25, damaged: 1, captured: 52), and 737 trucks, vehicles and jeeps (destroyed: 331, damaged: 18, captured: 387), while Azerbaijan lost 62 tanks (destroyed: 38, damaged: 16, abandoned: 1, captured: 7, captured but later lost: 1), 23 armoured fighting vehicles (destroyed: 6, damaged: 3, abandoned: 7, captured: 9), 76 trucks, vehicles and jeeps (destroyed: 40, damaged: 22, abandoned: 8, captured: 6), as well 11 old An-2 aircraft, used as unmanned bait in order for Armenia to reveal the location of air defence systems. Oryx only counts destroyed vehicles and equipment of which photo or videographic evidence is available, and therefore, the actual number of equipment destroyed is higher.[260]

Suspected war crimes

UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated that "indiscriminate attacks on populated areas anywhere, including in Stepanakert, Ganja and other localities in and around the immediate Nagorno-Karabakh zone of conflict, were totally unacceptable".[261] Amnesty International stated that both Azerbaijani and Armenian forces committed war crimes during recent fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh, and called on Azerbaijani and Armenian authorities to immediately conduct independent, impartial investigations, identify all those responsible, and bring them to justice.[262][263] Columbia University's Institute for the Study of Human Rights recognized that violent conflict affected all sides in the conflict but distinguished "the collateral damage of Azerbaijanis" from "the policy of atrocities such as mutilations and beheadings committed by Azerbaijani forces and their proxies in Artsakh."[264] Azerbaijan started an investigation on war crimes by Azerbaijani servicemen in November[265] and as of 14 December, has arrested four of its servicemen.[266]

Aftermath

Armenia

Shortly after the news about the signing the ceasefire agreement broke in the early hours of 10 November violent protests erupted in Armenia against Nikol Pashinyan, claiming he was a "traitor" for having accepted the peace deal.[268] Protesters also seized the parliament building by breaking a metal door, and pulled the President of the National Assembly of Armenia Ararat Mirzoyan from a car and beat him.[269][270] Throughout November, numerous Armenian officials resigned from their posts, including the Armenian minister of foreign affairs, Zohrab Mnatsakanyan,[271] the minister of defence, David Tonoyan,[272] head of the same ministry's military control service, Movses Hakobyan,[273] and the spokesman of Armenia's Defense Ministry, Artsrun Hovhannisyan.[274]

After the ceasefire agreement was signed, President Armen Sarksyan held a meeting with Karekin II, where they both made a call to declare 22 November as the Day of Remembrance of the Heroes who fell for the Defense of the Motherland in the Artsakh Liberation War.[275] On 16 November, he declared that snap parliamentary elections and Pashinyan's resignation were inevitable, proposing that a process be overseen and managed by an interim "National Accord Government".[276]

On 10 December, the Armenian media reported that an Azerbaijani citizen was detained at night near Berdavan in Tavush Province. It was reported that an Azerbaijani civilian was observed in Berdavan between 4:00 and 5:00 in the morning. The executive head of Berdavan, Smbat Mugdesyan, said that the NSS had taken him away and that he did not know other details. According to the Armenian media, a criminal case was opened against the detained citizen on suspicion of illegally crossing to the Armenian state border. The name of the detained Azerbaijani was not disclosed. According to the BBC Azerbaijani Service, Azerbaijan's Internal Affairs, Foreign Affairs and Defence Ministries said they had no information about the incident.[277]

On 12 December, Azerbaijani trucks, accompanied by the International Committee of the Red Cross and Russian peacekeepers, entered David Bek in Syunik Province of Armenia to pick up the bodies of fallen soldiers. Armenian officials refuted the media reports of Azerbaijani vehicles entering Goris.[278]

On 16 December, the family members of the missing Armenian soldiers gathered in front of the Armenian Ministry of Defence building, demanding information about their loved ones. They were not allowed into the building and Armenian military representatives did not give a response. A scuffle ensued, during which the family members of the missing Armenian soldiers broke through to the building.[279]

Azerbaijan

The peace agreement and the end of the war was seen as a victory and was widely celebrated in Azerbaijan.[280][281] On 10 November 2020, crowds waved flags in Baku after the peace deal was announced.[282] On that day, President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev gave a speech in which he mockingly said Nə oldu Paşinyan? ("What happened Pashinyan?"), which became an Internet meme in Azerbaijan and Turkey.[283][284] On 11 November, at a meeting with wounded Azerbaijani servicemen who took part in the war, Aliyev said that new orders and medals would be established in Azerbaijan, and that he gave appropriate instructions on awarding civilians and servicemen who showed "heroism on the battlefield and in the rear and distinguished themselves in this war." He also proposed the names of these orders and medals.[285] About a week later, at a plenary session of the Azerbaijani National Assembly, a draft law on amendments to the law "On the establishment of orders and medals of the Republic of Azerbaijan" was submitted for discussion.[286] Seventeen new orders and medals were established on the same day in the first reading in accordance with the bill "On the establishment of orders and medals of the Republic of Azerbaijan".[287] In mid-November, Aliyev and Azerbaijan's First Vice-president, Mehriban Aliyeva, visited Fuzuli and Jabrayil Districts, both of which were ghost towns in ruins after the Armenian forces occupied it in 1993.[288] Aliyev ordered the State Agency of Azerbaijan Automobile Roads to construct a new highway, starting from Alxanlı, which will connect Fuzuli to Shusha.[289] In Jabrayil, Aliyev stated that a "new master plan" will be drawn up to rebuild the city.[290]

27 September and 10 November were declared Memorial Day and Victory Day respectively,[291][292] although the latter's date was changed to 8 November as it overlapped with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's Memorial Day in Turkey.[293] It was also announced that the new station in the Baku Metro will be named 8 November at the suggestion of Aliyev.[294] On the same day, President Aliyev signed a decree on the establishment of the YASHAT Foundation to support the families of those wounded and killed during the war, and general control over the management of the foundation was transferred to the ASAN service.[295] On 2 December, the Association of Banks of Azerbaijan announced that the bank debts of servicemen and civilians killed during the war in Azerbaijan would be completely written off.[296] On 4 December, at 12:00 (GMT+4) local time, a moment of silence was held in Azerbaijan to commemorate the fallen soldiers of the war.[297][298] Flags were lowered across the country, and traffic halted, while ships moored in the Bay of Baku, as well as cars honked their horns.[299] A unity prayer was held at the Heydar Mosque in Baku in memory of those killed in the war, and Shaykh al-Islām Allahshukur Pashazadeh, chairman of the Religious Council of the Caucasus, said that "Sunnis and Shiites prayed for the souls of our martyrs together." Commemoration ceremonies were also held in mosques in Sumgayit, Guba, Ganja, Shamakhi, Lankaran, Shaki, in churches in Baku and Ganja, and in the synagogue of Ashkenazi Jews in Baku.[300] On 9 December, President Aliyev awarded 83 servicemen with the title of Hero of the Patriotic War,[301] 204 servicemen with Karabakh Order,[302] and 33 servicemen with Zafar Order.[303]

A victory parade was held on 10 December in honour of the Azerbaijani victory on Azadliq Square,[304] with 3,000 military servicemen who distinguished themselves during the war marched alongside military equipment, unmanned aerial vehicles and aircraft,[305] as well as Armenian war trophies,[306] and Turkish soldiers and officers.[307] Turkish President Erdoğan attended the military parade as part of a state visit to Baku.[308] In April 2021, Azerbaijan opened a Military Trophy Park featuring items from the conflict.[309]

According to peer-reviewed journal Caucasus Survey:[310]

…for the first time in the post-Soviet era, the Azerbaijani leadership has achieved a high degree of social solidarity. All opposition parties and organizations, including the Popular Front, Musavat, ReAl, and National Council, expressed their full support for the war. The citizens acquired a shared emotional experience of "making history". (...) The government received the stamp of approval from its most vicious critics. The authoritarian government and the civil society it long persecuted were united in the name of homeland. The definition of homeland, consequently, has been reduced to a military victory for the soil, not values or the rights or lives of its people. By supporting a war the government waged, both the opposition and civil society contributed to the creation of a new source and reserve of legitimacy for authoritarianism. Further, while the opposition and civil society criticized the regime in Russia for its authoritarianism and imperialist nationalism, the majority of them did not express misgivings about the no less authoritarian and imperialist politics of Turkey, and enthusiastically embraced ultra-right pan-Turkism.

Transfer of territories and flight of Armenian population

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The Armenian population of the territories ceded to Azerbaijan was forced to flee to Armenia, sometimes destroying their houses and livestock to keep them out of Azerbaijani hands.[311][312]

Turkish-Russian peacekeeping

Post-ceasefire clashes

Canada's boycott of arms exports to Turkey

In 2020, Canada suspended arms exports to Turkey due to accusations of the use of Canadian technology in the conflict, in violation of end-use assurances Turkey had given to Canada. Turkey criticised the Canadian decision.[313] In 2021, Canada prohibited arms exports to Turkey after an investigation verified the accusations.[314] Turkey protested that the embargo will harm bilateral relations and NATO alliance solidarity.[315]

Analysis

Nationalist sentiment

While Armenians and Azerbaijanis lived side by side under Soviet rule, the collapse of the Soviet Union contributed to racialisation and fierce nationalism, causing both Armenians and Azerbaijanis to stereotype each other, shaping rhetoric on both sides.[316] Before, during and after the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, the growth of anti-Armenian and anti-Azerbaijan sentiment resulted in ethnic violence, including pogroms against Armenians in Azerbaijan, as in Sumgait and Baku,[317][318][319][320] and against Azerbaijanis in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, as at Gugark and Stepanakert.[113][114][115][116]

Azerbaijani aims

In a 27 September 2020 interview, regional expert Thomas de Waal said that it was highly unlikely that hostilities were initiated by the Armenian side, as they were already in possession of the disputed territory and were incentivised to normalise the status quo, while "for various reasons, Azerbaijan calculate[d] that military action w[ould] win it something".[321] The suspected immediate goal of the Azerbaijani offensive was to capture the districts of Fuzuli and Jabrayil in southern Nagorno-Karabakh, where the terrain is less mountainous and more favourable for offensive operations.[76] Political scientist Arkady Dubnov of the Carnegie Moscow Center[322][323] believed that Azerbaijan had launched the offensive to improve Azerbaijan's position in a suitable season for hostilities in the terrain.[324]

Armenia's foreign policy

In the aftermath of the "Velvet Revolution" of April 2018, Pashinyan's ostensible reaffirmation of Armenia's pro-Russian orientation, the Kremlin responded in kind. But the repeated arrests of former Armenian President Robert Kocharyan, whom Putin has called "a true friend of Russia," have enraged the Kremlin. A series of moves, including the curtailment of intelligence ties with Russia and Pashinyan's replacement of pro-Russian personnel with less experienced loyalists, caused a rift in Russian-Armenian relations.[325]

Pashinyan's regime is convinced of its "democratic invincibility" and supports the view that Armenia's new democratic facade must receive more support from Brussels and Washington.[325] However, as the world trends in a more realpolitik direction, whether or not Armenia is a democracy may not matter to the US under Trump's presidency. Despite EU support for Armenia's reforms, analysis from the International Crisis Group believes that Pashinyan may be expecting too much from Europe.[326] The long-standing security problems, most notably the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, are ignored by the new elite.[325] As Gerard Libaridian, the foreign policy adviser to Armenia's first president, has pointed out, Pashinyan's recasting of the Karabakh issue from one of self-determination to one of Armenian expansionism was another huge mistake.[327][328]

Turkey and Russia

The geostrategic interests of Russia and Turkey in the region were widely commented upon during the war.[329] Both were described as benefiting from the ceasefire agreement, with The Economist stating that for Russia, China and Turkey, "all sides stand to benefit economically".[330] In late October, massed Russian airstrikes targeted a training camp for Failaq al-Sham, one of the largest Turkish-backed Sunni Islamist rebel groups in Syria's Idlib province, killing 78 militants in an act widely interpreted as a warning shot to Ankara over the latter's involvement in the Nagorno-Karabakh fighting.[331][332]

Turkey

Azerbaijan and Turkey are bound by ethnic, cultural and historic ties, and both countries refer to their relationship as being one between "two states, one nation".[333] Turkey (then the Ottoman Empire) helped Azerbaijan, previously part of the Russian Empire gain its independence in 1918, and became the first country to recognise Azerbaijan's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.[334] Turkey has also been the guarantor of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, an exclave of Azerbaijan, since 1921.[335][336] Other commentators have seen Turkey's support for Azerbaijan as part of an activist foreign policy, linking it with neo-Ottoman policies in Syria, Iraq, and the Eastern Mediterranean.[337][338] Turkey's highly visible role in the conflict was described by Armenians as a continuation of the Armenian genocide, the mass murder and expulsion of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman government, particularly given Turkey's continued denial of the genocide.[339][340][341][342] Turkey provided military support to Azerbaijan, including military experts and Syrian mercenaries.[330] The transport communications stipulated by the ceasefire agreement, linking Nakhchivan and the main part of Azerbaijan through Armenia, would provide Turkey with trade access to Central Asia and China's Belt and Road Initiative.[330]

Russia

Russia had sought to maintain good relations with Azerbaijan and had sold weapons to both parties. Even prior to the war, Russia had possessed a military base in Armenia as part of a military alliance with Armenia, and thus was obligated by treaty to defend Armenia in the case of a war. Like in Syria and in Libya's ongoing civil war, Russia and NATO-member Turkey therefore had opposing interests.[343] Turkey appeared to use the conflict to attempt to leverage its influence in the South Caucasus along its eastern border, using both military and diplomatic resources to extend its sphere of influence in the Middle East, and to marginalise the influence of Russia, another regional power.[344][345] Russia had historically pursued a policy of maintaining neutrality in the conflict, and Armenia never formally requested aid.[75] According to the director of the Russia studies program at the CNA, at the beginning of the war Russia was judged to be unlikely to intervene militarily unless Armenia incurred drastic losses.[75] The Russian MoFA also released a statement, saying that Russia will provide Armenia with "all the necessary assistance" if the war continued on the territories of Armenia, as both countries are part of the Collective Security Treaty Organization.[346][347] Nonetheless, when the Azerbaijani forces reportedly struck the Armenian territories on 14 October 2020, Russia did not directly interfere in the conflict.[348] In a piece published by the Russian broadsheet Vedomosti on 10 November, Konstantin Makienko, a member of the State Duma Defence Committee, wrote that the geopolitical consequences of the war were "catastrophic" not only for Armenia but for Russia as well, because Moscow's influence in the Southern Caucasus had dwindled while "the prestige of a successful and feisty Turkey, contrariwise, had increased immensely".[349] Alexander Gabuev of the Carnegie Moscow Center took the opposite view, describing the peace agreement as "a win for Russia", as it had "prevented the conclusive defeat of Nagorno-Karabakh" and, by placing Russia in charge of the strategic Lachin corridor, boosted the country's leverage in the region.[350]

The relative success of Azerbaijan in meeting its strategic goals to gain control over Nagorno-Karabakh via the use of military force may have influenced the Russian decision to invade Ukraine in 2022.[351]

Military tactics

Azerbaijan's oil wealth allowed a consistently higher military budget than Armenia,[330] and it purchased advanced weapons systems from Israel, Russia and Turkey.[133] Despite the similar size of both militaries, Azerbaijan possessed superior tanks, armoured personnel carriers and infantry fighting vehicles,[136] and had also amassed a fleet of Turkish and Israeli drones. Armenia built its own drones, but these were greatly inferior to the Turkish and Israeli drones owned by Azerbaijan.[136] Azerbaijan had a quantitative advantage in artillery systems, particularly self-propelled guns and long-range multiple rocket launchers, while Armenia had a minor advantage in tactical ballistic missiles.[23] Because of the air defence systems of both sides, there was little use of manned aviation during the conflict.[136] In the opinion of military analyst Michael Kofman, Director of the Russia Studies Program at the CNA and a Fellow at the Kennan Institute, Azerbaijan deployed mercenaries from Syria to minimise Azeri troop casualties: "They took quite a few casualties early on, especially in the south-east, and these mercenaries were essentially used as expendable assault troops to go in the first wave. They calculated quite cynically that if it turned out these offensives were not successful early on, then it was best these casualties would be among mercenaries not Azerbaijani forces."[352]

According to Gustav Gressel, a Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, the Armenian Army was superior to the Azerbaijani Army on a tactical level, with better officers, more agile leadership, and higher motivation in soldiers but these were overcome by Azerbaijan's innovative use of drones to discover Armenian forward and reserve positions followed by conventional artillery and ballistic missiles to isolate and destroy Armenian forces.[144] Gressel argues that European militaries are not better prepared for anti-drone warfare than Armenia's (with only France and Germany having some limited jamming capabilities) and warns that a lack of gun-based self-propelled air-defence systems and radar systems capable of tracking drones (using "plot-fusion" of several radar echoes) makes European forces extremely vulnerable to loitering munitions and small drones.[144]

In the opinion of a Forbes magazine contributor, Azerbaijan managed to inflict a devastating and decisive defeat through adept usage of sophisticated military hardware which avoided bogging down in a costly war of attrition. According to Forbes, Azerbaijan had prepared itself for tomorrow's war rather than a repeat of yesterday's war.[353]

The International Institute for Strategic Studies presented a summary of analyses by Russian military experts, who concluded that the Azerbaijani victory was not just a result of drone warfare and Turkish assistance, but could actually be attributed to a number of other factors, such as a more professional army with recent battlefield experience, employment by Armenia of Soviet-era tactics against the modern warfare waged by Azerbaijan, a strong national will to fight on part of Azerbaijan compared to irresolute Armenian leadership, and the Armenians believing their own propaganda and underestimating the enemy.[354]

In the opinion voiced by Russian military expert Vladimir Yevseev after the war, for unclear reasons Armenia appeared not to have executed the mobilisation it had announced and hardly any mobilised personnel were deployed to the conflict area.[355]

Drone warfare

Azerbaijan made devastating use of drones and sensors, demonstrating what The Economist described as a "new, more affordable type of air power".[133] Azerbaijani drones, notably the Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2, carried out precise strikes as well as reconnaissance, relaying the coordinates of targets to Azerbaijani artillery.[79] Commentators noted how drones enabled small countries to conduct effective air campaigns, potentially making low-level conflicts much more deadly.[356] Close air support was provided by specialised suicide drones such as the Israeli-made IAI Harop loitering munition, rendering tanks vulnerable and suggesting the need for changes to armoured warfare doctrine.[357] Another suicide drone, the Turkish-made STM Kargu, was also reportedly used by Azerbaijan.[358][43]

Targeting of pipelines

Concerns were raised about the security of the petroleum industry in Azerbaijan.[359][360] Azerbaijan claimed that Armenia targeted, or tried to target, the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, which accounted for around 80% of country's oil exports, and the Baku–Novorossiysk pipeline.[361][362][363] Armenia rejected the accusations.[364]

Use of propaganda

Both sides engaged in extensive propaganda campaigns through official mainstream and social media accounts magnified online,[80] including in Russian media. Video from drones recording their kills was used in highly effective Azerbaijani propaganda.[79][133] In Baku, digital billboards broadcast high-resolution footage of missiles striking Armenian soldiers, tanks, and materiel. Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev told Turkish television that Azerbaijani-operated drones had reduced the number of Azerbaijan's casualties, stating, "These drones show Turkey's strength" and "empower" Azerbaijanis.[136]

Cyberwarfare

Hackers from Armenia and Azerbaijan as well as their allied countries have waged cyberwarfare, with Azerbaijani hackers targeting Armenian websites and posting Aliyev's statements,[365] and Greek hackers targeting Azerbaijani governmental websites.[366] There have been coordinated messages posted from both sides. Misinformation and videos of older events and other conflicts have been shared as new. New social media accounts posting about Armenia and Azerbaijan have spiked, with many from authentic users, but many inauthentic also.[367][368] According to the EU Parliament, Azerbaijani information operations also specifically aimed at harassing Armenia social media users.[369]

Official statements

Armenia and Artsakh

On 27 September 2020, the Prime Minister of Armenia, Nikol Pashinyan, accused the Azerbaijani authorities of a large-scale provocation. The Prime Minister stated that the "recent aggressive statements of the Azerbaijani leadership, large-scale joint military exercises with Turkey, as well as the rejection of OSCE proposals for monitoring" indicated that the aggression was pre-planned and constituted a major violation of regional peace and security.[370] The next day, Armenia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) issued a statement, noting that the "people of Artsakh were at war with the Turkish–Azerbaijani alliance".[371]

The same day, the Armenian ambassador to Russia, Vardan Toganyan, did not rule out that Armenia may turn to Russia for fresh arms supplies.[372] On 29 September 2020, Prime Minister Pashinyan stated that Azerbaijan, with military support from Turkey, was expanding the theatre into Armenian territory.[373] On 30 September 2020, Pashinyan stated that Armenia was considering officially recognising the Republic of Artsakh as an independent territory.[374] The same day, the Armenian MoFA stated that the Turkish Air Force had carried out provocative flights along the front between the forces of the Republic of Artsakh and Azerbaijan, including providing air support to the Azerbaijani army.[375]

On 1 October 2020, the President of Artsakh, Arayik Harutyunyan, stated that Armenians needed to prepare for a long-term war.[376] Two days later, the Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) Foreign Ministry called on the international community to recognise the independence of the Republic of Artsakh in order to restore regional peace and security.[377]

On 6 October 2020, the Armenian prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan, stated that the Armenian side was prepared to make concessions, if Azerbaijan was ready to reciprocate.[378]

On 9 October 2020, Armen Sarkissian demanded that international powers, particularly, the United States, Russia and NATO, do more to stop Turkey's involvement in the war and warned that Ankara is creating "another Syria in the Caucasus".[379]

On 21 October 2020, Nikol Pashinyan stated that "it is impossible to talk about a diplomatic solution at this stage, at least at this stage", since the compromise option is not acceptable for Azerbaijan, while the Armenian side stated many times that it is ready to resolve the issue through compromises. Pashinyan said that "to fight for the rights of our people means, first of all, to take up arms and commit to the protection of the rights of the homeland".[380]

On 12 November 2020, Pashinyan addressed his nation, saying that "Armenia and the Armenian people are living extremely difficult days. There is sorrow in the hearts of all of us, tears in the eyes of all of us, pain in the souls of all of us". The prime minister pointed out that the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Armenia reported that the war "must be stopped immediately". And the President of Artsakh warned that if the hostilities do not stop, Stepanakert could be lost in days. Pashinyan also stated that the Karabakh issue was not resolved and is not resolved and that the international recognition of the Artsakh Republic is becoming an absolute priority.[381]

Azerbaijan

According to the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence, the Armenian military violated the ceasefire 48 times along the line of contact on 26 September 2020, the day before the conflict. Azerbaijan stated that the Armenian side attacked first, prompting an Azerbaijani counter-offensive.[382]

On 27 September 2020, Azerbaijan accused Armenian forces of a "willful and deliberate" attack on the front line[383] and of targeting civilian areas, alleging a "gross violation of international humanitarian law".[384] On 28 September 2020, it stated that Armenia's actions had destroyed the peace negotiations through an act of aggression,[385] alleged that a war had been launched against Azerbaijan, mobilised the people of Azerbaijan, and declared a Great Patriotic War.[386] It then stated that the deployment of the Armenian military in Nagorno-Karabakh constituted a threat to regional peace and accused Armenia of propagandising, adding that the Azerbaijani military was operating according to international law.[387] The Azerbaijani authorities issued a statement accusing the Armenian military of purposefully targeting civilians, including women and children.[388] The Azerbaijani Minister of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) denied any reports of Turkish involvement, while admitting military-technical cooperation with Turkey and other countries.[389]

On 29 September 2020, the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, said that Armenian control of the area and aggression had led to the destruction of infrastructure and mosques, caused the Khojaly massacre and resulted in cultural genocide, and was tantamount to state-backed Islamophobia and anti-Azerbaijani sentiment.[390] The Azerbaijani MoFA demanded that Armenia stop shelling civilians and called on international organisations to ensure Armenia followed international law.[391] Azerbaijan denied reports of mercenaries brought in from Turkey by Azerbaijan,[392][393] and the First Vice-president of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Mehriban Aliyeva, stated that Azerbaijan had never laid claim to others' territory nor committed crimes against humanity.[394]

On 3 October 2020, Aliyev stated that Armenia needed to leave Azerbaijan's territory (in Nagorno-Karabakh) for the war to stop.[395] The next day, Aliyev issued an official statement that Azerbaijan was "writing a new history", describing Karabakh as an ancient Azerbaijani territory and longstanding home to Azerbaijanis, and claiming that Armenians had occupied Azerbaijan's territory, destroying its religious and cultural heritage, for three decades. He added that Azerbaijan would restore its cities and destroyed mosques and accused Armenia of distorting history.[396]

Two days later, Aliyev's aide, Hikmat Hajiyev, said that Armenia had deployed cluster munitions against cities,[397] however this had not been verified by other sources. On 7 October 2020, Azerbaijan officially notified members of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, the Conference of European Constitutional Courts, the Association of Asian Constitutional Courts and similar organisations that it had launched the operation in line with international law to re-establish its internationally recognised territorial integrity and for the safety of its people.[398] He also accused Armenia of ethnic discrimination on account of the historical expulsion or self-exile of ethnic minority communities, highlighting its mono-ethnic population.[399]

On 10 October 2020, Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Jeyhun Bayramov stated that the truce signed on the same day was temporary.[400] Despite this, Aliyev stated that both parties were now attempting to determine a political resolution to the conflict.[401]

On 21 October 2020, Aliyev stated that Azerbaijan did not rule out the introduction of international observers and peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh, but will put forward some conditions when the time comes.[402] He then added that Azerbaijan did not agree for a referendum in Nagorno-Karabakh,[403] but didn't exclude the cultural autonomy of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh,[402] and reaffirmed that the Azerbaijan considers Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh as their citizens, promising security and rights.[404]

On 26 October 2020, Aliyev stated that the Azerbaijani government will inspect and record the destruction by Armenian forces in Armenian-occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.[405]

Allegations of third-party involvement

Because of the geography, history, and sensitivities of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, accusations, allegations, and statements have been made of involvement by third-party and international actors.

International reactions

See also

- 2014 Armenian–Azerbaijani clashes

- Actions in support of Azerbaijan in Iran (2020)

- 2023 Azerbaijani offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh

- Armenia–Azerbaijan border crisis

- List of territorial disputes

- Republic of Armenia v. Republic of Azerbaijan (ICJ case)

Notes

- ^ Denied by Azerbaijan[5][6] and Turkey.[7]

- ^ On 21 October 2021, the Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Azerbaijan published a list of dead servicemen. It said 2,908 people were killed during the war,[37] although at least two of the soldiers named were killed after the conflict ended,[51][52] leaving a total of 2,906 servicemen confirmed killed in the war.

- ^ a b By 27 September 2021, 84 civilians were confirmed killed in the conflict, 80 of which died in the Republic of Artsakh and 4 were killed in Armenia.[1] [2] Another 22 were still missing.[3] Subsequently, the number of civilians missing was updated to 21 by 21 March 2022,[4] bringing the total number of confirmed civilian fatalities to 85.

- ^ Nagorno-Karabakh was an autonomous region of Azerbaijan during the Soviet era, and is internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan. At the end of the Soviet period, it was recorded as being populated by 76.9% Armenians, 21.5% Azerbaijanis, and 1.5% other groups, totalling 188,685 persons, in the 1989 census. The surrounding districts, occupied by the Republic of Artsakh since the 1994 ceasefire, were recorded in the 1979 census to have a population of 97.7% Azerbaijanis, 1.3% Kurds, 0.7% Russians, 0.1% Armenians, and 0.1% Lezgins, for a total of 186,874 persons. This does not include the populations of Fuzuli District and Agdam District, which were only partially under Armenian control before the 2020 war.

References

- ^ "Принуждение к конфликту" [Coercion to conflict]. Kommersant (in Russian). 16 October 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (29 January 2021). "Armenia and Azerbaijan: What Sparked War and Will Peace Prevail?". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

Armenia has said that Turkey was directly involved in the fighting in and around Nagorno-Karabakh, and that a Turkish F-16 fighter shot down an Armenian jet. Turkey denied those accusations.

- ^ Tsvetkova, Maria; Auyezov, Olzhas (9 November 2020). "Analysis: Russia and Turkey keep powder dry in Nagorno-Karabakh conflict". Reuters. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

Turkey's support for Azerbaijan has been vital, and Azerbaijan's superior weaponry and battlefield advances have reduced its incentive to reach a lasting peace deal. Ankara denies its troops are involved in fighting but Aliyev has acknowledged some Turkish F-16 fighter jets remained in Azerbaijan after a military drill this summer, and there are reports of Russian and Turkish drones being used by both sides.

- ^ "Turkey denies direct involvement in Azerbaijan's Karabakh campaign".

- ^ "Azerbaijan denies Turkey sent it fighters from Syria". 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh: Azerbaijan accuses Armenia of rocket attack". The Guardian. 5 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Türkiye'nin Dağlık Karabağ'a paralı asker gönderdiği iddiası" (in Turkish). Deutsche Welle. 29 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Ed Butler (10 December 2020). "The Syrian mercenaries used as 'cannon fodder' in Nagorno-Karabakh". BBC. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

Although Azerbaijan and its ally Turkey deny the use of mercenaries, researchers have amassed a considerable amount of photographic evidence, drawn from videos and photographs the fighters have posted online, which tells a different story.

- ^ Cookman, Liz (5 October 2020). "Syrians Make Up Turkey's Proxy Army in Nagorno-Karabakh". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

According to sources within the Syrian National Army (SNA), the umbrella term for a group of opposition militias backed by Turkey, around 1,500 Syrians have so far been deployed to the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region in the southern Caucasus ... Shortly after conflict erupted between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Turkey sought to mobilize the SNA, sometimes called Turkey's proxy army ... The first fighters were transferred in late September to southern Turkey and then flown from Gaziantep to Ankara, before being transferred to Azerbaijan on Sept. 25.

- ^ a b "Deal Struck to End Nagorno-Karabakh War". The Moscow Times. 10 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "'One nation, two states' on display as Erdogan visits Azerbaijan for Karabakh victory parade". France24. 10 December 2020.

Azerbaijan's historic win was an important geopolitical coup for Erdogan who has cemented Turkey's leading role as a powerbroker in the ex-Soviet Caucasus region.

- ^ "Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia sign Nagorno-Karabakh peace deal". BBC. 10 November 2020.

The BBC's Orla Guerin in Baku says that, overall, the deal should be read as a victory for Azerbaijan and a defeat for Armenia.

- ^ "Release of the Press Service of the President". president.az. Official website of the President of Azerbaijan. 4 October 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Major General Mayis Barkhudarov: "We will fight to destroy the enemy completely". Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence. 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020.

- ^ "President Ilham Aliyev congratulates 1st Army Corps Commander Hikmet Hasanov on liberation of Madagiz from occupation". apa.az. 3 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

President Ilham Aliyev has congratulated 1st Army Corps Commander Hikmet Hasanov on liberation of Madagiz, APA reports.

- ^ a b "Release of the Press Service of the President". Azerbaijan State News Agency. 19 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Azerbaijan, President Ilham Aliyev congratulated Chief of the State Border Service (SBS), Colonel General Elchin Guliyev on raising the Azerbaijani flag over the Khudafarin bridge, liberating several residential settlements with the participation of the SBS, and instructed to convey his congratulations to all personnel. Colonel General Elchin Guliyev reported that the State Border Service personnel will continue to decently fulfill all the tasks set by the Commander-in-Chief.

- ^ a b "Jalal Harutyunyan wounded, Mikael Arzumanyan appointed Artsakh Defense Minister". 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Artsakh Defense Army deputy commander killed". 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Արցախում զոհվել է ՊԲ փոխհրամանատար, գնդապետ Հովհաննես Սարգսյանը" [Deputy Commander of the Defence Army, Colonel Hovhannes Sargsyan was killed in Artsakh]. Lurer.com (in Armenian). 18 November 2020. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Հայաստանի Ազգային հերոս Վահագն Ասատրյանն Օմարի բարձունքներն անառիկ պահեց, բայց ընկավ Հադրութը պաշտպանելիս" [Armenian national hero Vahagn Asatryan kept Omar heights invincible, but fell while defending Hadrut]. 1lurer.am (in Armenian). 1 January 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Tiran Khachatryan – National Hero of the Republic of Armenia". armradio.am. Public Radio of Armenia. 22 October 2020.

- ^ "President Ilham Aliyev congratulates Commander of 1st Army Corps Hikmat Hasanov on liberation of Madagiz". Trend News Agency. 3 October 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, Two Weeks In". War on the Rocks. 14 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ a b c "Эксперт оценил потери Армении и Азербайджана в Нагорном Карабахе" (in Russian). Moskovsky Komsomolets. 7 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Qarabağın qəlbi necə azad olundu: 300 spartalının əfsanəsi gerçək oldu Şuşada". Bizim Yol (in Azerbaijani). 9 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Aliyev, Ilham (26 October 2020). "Release of the Press Service of the President". President.az. Presidential Administration of Azerbaijan. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Bu gün general olan 4 hərbçi kimdir?" [Who are the 4 servicemen that became generals today?]. Milli.az (in Azerbaijani). 7 December 2020. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ahmad, Murad (3 December 2020). ""Şuşaya ermənilərin içindən keçib getdik, xəbərləri olmadı" – XTD üzvü +Video" ["We went to Shusha through Armenians, they didn't know" – SOF member + Video]. Qafqazinfo (in Azerbaijani). Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Kazimoglu, Mirmahmud (10 December 2020). "Xarici Kəşfiyyat Xidmətinin YARASA xüsusi bölməsi ilk dəfə nümayiş etdirildi". Report Information Agency (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Syrian rebel fighters prepare to deploy to Azerbaijan in sign of Turkey's ambition". Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Everything We Know About The Fighting That Has Erupted Between Armenia And Azerbaijan". The Drive. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "46 servicemen of Armenia NSS border troops killed during NK war". armenpress.am.

- ^ "Law enforcement: 65 Armenia Police officers died in Artsakh war". news.am. 29 September 2023.

- ^ Hovhannisyan, Samvel (16 January 2021). "Дуэль Ванецяна и Кярамяна – стреляют друг в друга, попадают в Армению" [Duel of Vanetsyan and Kyaramyan – shoot each other, end up in Armenia]. ArmenianReport (in Russian). Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "The Artsakh War brought about Armenia's first all-women military unit". 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Üç minə yaxın qazi təklif olunan işdən imtina edib". Report İnformasiya Agentliyi (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "List of servicemen who died as Shehids in the Patriotic War". Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "SOHR exclusive | Death toll of mercenaries in Azerbaijan is higher than that in Libya, while Syrian fighters given varying payments". Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 3 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "What Open Source Evidence Tells Us About The Nagorno-Karabakh War". Forbes. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Bensaid, Adam (29 September 2020). "A military breakdown of the Azerbaijan–Armenia conflict". TRTWorld. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Frantzman, Seth J. (1 October 2020). "Israeli drones in Azerbaijan raise questions on use in the battlefield". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Son dakika... Görüntü dünyayı çalkaladı! SİHA vurdu, bir başka drone..." (in Turkish). Milliyet. 1 October 2020. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b "İlk kez Libya'da kullanılmıştı! Bu kez Azerbaycan'da görüntülendi" (in Turkish). CNN Türk. 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Azerbaijani Military Retools Old Crop Duster Planes as Attack Drones". Hetq Online. 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Missiles, rockets and drones define Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict". The Jerusalem Post. 4 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Azerbaijan shoots down Armenian Su-25 fighter jet". TRT World. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Cities under fire as Armenia-Azerbaijan fighting intensifies". RTL Today. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "Armenia, Azerbaijan announce new attempt at cease-fire". AP News. 17 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "Село Тапкаракоюнлу, примерно в 60 километрах от города Гянджа. Военный показывает журналистам ракету "Смерч" перед разминированием" (in Russian). BBC Russian Service. 24 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Azerbaijani used TB2 drone to destroy second S-300 SAM of Armenia". Global Defense Corp. 11 October 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Four Azerbaijanis killed in mine blast in Fuzuli region". AzerNews.az. 28 November 2020.

- ^ Yazar, Yazar (28 November 2020). "Azərbaycan əsgəri Şuşa yolunda minaya düşərək şəhid oldu". Sozcu.az. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ "Vətən müharibəsində yaralanan hərbçilərin sayı açıqlanıb". Report.az. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Khulian, Artak (10 February 2021). "Armenia, Azerbaijan Exchange More Prisoners". www.azatutyun.am.

- ^ "Azerbaijani captives, including Shahbaz Guliyev and Dilgam Asgarov, who were held hostage by Armenians, brought home". www.news.az. 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh battles | Fatalities among Turkish-backed Syrian mercenaries jump to 250, and more bodies arrive in Syria". The Syrian Observatory For Human Rights. 6 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan's speech at the National Assembly during the discussion of the performance report of the Government Action Plan for 2021". primeminister.am. The Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia. 13 April 2022. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022.

The number of victims of the 44-day war is 3825 by today's data.

- ^ a b c d "187 Armenian troops still MIA, 21 civilians missing in 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war". armenpress.m. Armenpress. 21 March 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Around 11,000 Armenian soldiers wounded and got sick in recent Artsakh war, military official says". Panorama. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b "МИД Армении и Красный Крест объединят усилия для решения вопроса пленных". Armenian Report (in Russian). 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Civilian death toll in Armenian attacks reaches 100". AzerNews. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Artsakh Ombudsman's Office updates interim report on killing of civilians by Azerbaijani forces". armenpress.am.

- ^ "Caucasus: 4 Journalists Injured in Nagorno-Karabakh Fighting". Voice of America. 1 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "3 vətəndaşımız Ermənistanda əsir-girovluqda saxlanılır". axar.az. 17 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Armenia awaits complete numbers of killed soldiers and POWs". OC-Media. 10 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Welle (dw.com), Deutsche. "Nagorno-Karabakh: Russian helicopter shot down over Armenia". DW.

- ^ "Russian teenager dies in missile attack on Ganja". NEWSru. 24 October 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Two French journalists seriously wounded after shelling in Nagorno-Karabakh". Reuters. 1 October 2020. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "МИД РФ: Российские журналисты в Карабахе получили средние и тяжелые ранения" (in Russian). Rossiyskaya Gazeta. 8 October 2020. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Iran comes under attack as fighting between Armenia–Azerbaijan spreads across border". Almasdar News. 3 October 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: Bachelet warns of possible war crimes as attacks continue in populated areas". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Uneasy peace takes hold in contested region of Azerbaijan". PBS NewsHour. 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Глава МИД Армении назвал число беженцев из-за ситуации в Карабахе" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Nearly 90,000 people displaced, lost homes and property in Nagorno Karabakh". ArmenPress. 24 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Kofman, Michael (2 October 2020). "Armenia–Azerbaijan War: Military Dimensions of the Conflict". russiamatters.org. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

On 27 September 2020, Azerbaijan launched a military offensive, resulting in fighting that spans much of the line of contact in the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh...