Sedition Act (Singapore)

| Sedition Act 1948 | |

|---|---|

Old Parliament House, photographed in January 2006 | |

| Federal Legislative Council, Federation of Malaya | |

| |

| Citation | Sedition Ordinance 1948 (No. 14 of 1948, Malaya), 2020 Revised Edition—Sedition Act 1948 (Singapore) |

| Enacted by | Federal Legislative Council, Federation of Malaya |

| Enacted | 6 July 1948[1] |

| Royal assent | 15 July 1948[1] |

| Commenced | 19 July 1948 (Peninsular Malaysia);[1][2] extended to Singapore on 28 May 1964[3] |

| Repealed | 2 November 2022 |

| Legislative history | |

| Bill title | Sedition Bill 1948 |

| Introduced by | E. P. S. Bell (Acting Attorney-General). |

| First reading | 6 July 1948[4] |

| Second reading | 6 July 1948[4] |

| Third reading | 6 July 1948[4] |

| Repealed by | |

| Sedition (Repeal) Act 2021 | |

| Status: Repealed | |

The Sedition Act 1948 was a Singaporean statute law which prohibited seditious acts and speech; and the printing, publication, sale, distribution, reproduction and importation of seditious publications. The essential ingredient of any offence under the Act was the finding of a "seditious tendency", and the intention of the offender is irrelevant. The Act also listed several examples of what is not a seditious tendency, and provides defences for accused persons in a limited number of situations.

A notable feature of the Sedition Act was that in addition to punishing actions that tend to undermine the administration of government, the Act also criminalized actions which promoted feelings of ill-will or hostility between different races or classes of the population. In contrast to arrests and prosecutions in the 1950s and 1960s which involved allegations of fomenting disaffection against the government, those in the 21st century such as the District Court cases of Public Prosecutor v. Koh Song Huat Benjamin (2005) and Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong (2009) had centred around acts and publications tending to have the latter effect. Academics had raised concerns about whether the Sedition Act was satisfactorily interpreted in those cases, and whether the use of "feelings" as a yardstick to measure seditious tendencies is appropriate.

In Ong Kian Cheong, the accused persons argued that in order for section 3(1)(e) of the Act to be consistent with the right to freedom of speech and expression guaranteed to Singapore citizens by Article 14(1)(a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1985 Rev. Ed., 1999 Reprint), it had to be limited to actions expressly or impliedly inciting public disorder. The District Court disagreed, stating that if Parliament had intended to include this additional requirement, it would have expressly legislated to that effect in the Act. The High Court and Court of Appeal have yet to render any judgment on the issue. According to one legal scholar, Koh Song Huat Benjamin and Ong Kian Cheong indicate that in Singapore freedom of speech is not a primary right, but is qualified by public order considerations couched in terms of racial and religious harmony. It has also been posited that if Article 14 is properly interpreted, section 3(1)(e) of the Sedition Act is not in line with it.

On 2 November 2022, the Sedition Act was repealed.[5]

History

[edit]Common law

[edit]

Sedition, which is committed when spoken or written words are published with seditious intent, was a criminal offence under English common law. It emerged in an era where political violence threatened the stability of governments.[6] The Star Chamber, in the case of De Libellis Famosis (1572),[7] defined seditious libel (that is, sedition in a printed form) as the criticism of public persons or the government, and established it as a crime. The crime of sedition was premised on the need to maintain respect for the government and its agents, for criticism of public persons or the government undermines respect for public authorities. Even though the Star Chamber was later dissolved, seditious libel had become established as a common law offence.[8]

Originally designed to protect the Crown and government from any potential uprising, sedition laws prohibited any acts, speech, or publications or writing that were made with seditious intent. Seditious intent was broadly defined by the High Court of Justice in R. v. Chief Metropolitan Stipendiary, ex parte Choudhury (1990)[9] as "encouraging the violent overthrow of democratic institutions".[10] In the important common law jurisdictions, "seditious libel means defiance or censure of constituted authority leading to foreseeable harm to public order",[11] and the Court in ex parte Choudhury clarified that constituted authority refers to "some person or body holding public office or discharging some public function of the state".[12]

Legislation

[edit]Sedition laws were initially introduced in Singapore and the other Straits Settlements (S.S.) through the Sedition Ordinance 1938.[13][14] Similar legislation was introduced in the Federated Malay States (F.M.S.) in 1939, in the form of the Sedition Enactment 1939.[15] While the Sedition Ordinance 1938 (S.S.) remained in force in Singapore after it became a Crown colony in 1946 and a self-governing state in 1959, in the Federation of Malaya the law was replaced by the Sedition Ordinance 1948[1] which was introduced by the British government to curb opposition to colonial rule.[14] Speaking during a Federal Legislative Council debate on 6 July 1948, the Acting Attorney-General of the Federation, E. P. S. Bell, said the Government considered it "convenient to have a Federal law" to replace the various sedition enactments in the Federation which were based on a model ordinance "sent to this country some years ago by the Colonial Office". The Ordinance was largely a re-enactment of the F.M.S. Enactment, though the penalties for the offences under section 4 were increased and two new clauses (now sections 9 and 10) were included.[4]

The 1948 Ordinance was extended to Singapore on 28 May 1964 following its merger with the Federation together with Sabah and Sarawak to form Malaysia. Singapore retained the legislation after its separation from Malaysia with effect from 9 August 1965.[14] The current version of the legislation in Singapore is the Sedition Act (Chapter 290, 1985 Revised Edition).[16]

Repeal in 2022

[edit]On 13 September 2021, the government introduced a bill in parliament to repeal the Sedition Act. The Ministry of Home Affairs cited its "limited application" as a reason for its repeal, and added that new laws like the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act, the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019, the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act 2016, the Undesirable Publications Act, the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act, and specific provisions under the Penal Code were sufficient to address issues "in a more targeted and calibrated manner".[17]

On 5 October 2021, Parliament passed the Sedition (Repeal) Bill.[18] It was assented to by President Halimah Yacob on 29 October 2021 and came into effect on 2 November 2022.[19][20]

Seditious tendency

[edit]Meaning

[edit]The Sedition Act[16] criminalizes seditious acts and speech; and the printing, publication, sale, distribution, reproduction and importation of seditious publications. The maximum penalty for a first offender is a fine of up to S$5,000 or imprisonment not exceeding three years or both, and for a subsequent offender imprisonment not exceeding five years. The court is required to forfeit any seditious publication found in an offender's possession or used in evidence at the trial, and may order that it be destroyed or otherwise disposed of.[21] No person may be convicted on the uncorroborated testimony of a single witness.[22]

As the Act defines something as seditious if it has a "seditious tendency",[23] a crucial element underpinning the offences mentioned above is the requirement to prove a seditious tendency which is defined in sections 3(1) and (2):

3.— (1) A seditious tendency is a tendency —

- (a) to bring into hatred or contempt or to excite disaffection against the Government;

- (b) to excite the citizens of Singapore or the residents in Singapore to attempt to procure in Singapore, the alteration, otherwise than by lawful means, of any matter as by law established;

- (c) to bring into hatred or contempt or to excite disaffection against the administration of justice in Singapore;

- (d) to raise discontent or disaffection amongst the citizens of Singapore or the residents in Singapore;

- (e) to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between different races or classes of the population of Singapore.

(2) Notwithstanding subsection (1), any act, speech, words, publication or other thing shall not be deemed to be seditious by reason only that it has a tendency —

- (a) to show that the Government has been misled or mistaken in any of its measures;

- (b) to point out errors or defects in the Government or the Constitution as by law established or in legislation or in the administration of justice with a view to the remedying of such errors or defects;

- (c) to persuade the citizens of Singapore or the residents in Singapore to attempt to procure by lawful means the alteration of any matter in Singapore; or

- (d) to point out, with a view to their removal, any matters producing or having a tendency to produce feelings of ill-will and enmity between different races or classes of the population of Singapore,

if such act, speech, words, publication or other thing has not otherwise in fact a seditious tendency.

Although this statutory definition broadly corresponds to its common law counterpart,[24] there are two key differences. First, unlike the common law offence which requires evidence of a seditious intent, an offender's intention is irrelevant under the Sedition Act,[25] and it suffices that the act possesses the requisite seditious tendency.[26] Thus, it is immaterial that the offender failed to foresee or misjudged the risk that his or her act would be seditious.[27]

Secondly, section 3(1)(e) differs from the classic common law idea of sedition because there is no requirement that the seditious tendency has to be directed against the maintenance of government. A District Court held in Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong (2009)[28] that on a plain and literal reading, there is no suggestion that Parliament intended to embody the common law of seditious libel into section 3(1)(e).[29] Since prosecutions under the Sedition Act since 1966 have been based on section 3(1)(e), a distinctive feature of the use of the Act in the 21st century is that it has primarily been employed to deal with disruptions to racial and religious harmony.[30]

Interpretation of section 3(1)(e)

[edit]Feelings of ill-will and hostility

[edit]In Public Prosecutor v. Koh Song Huat Benjamin (2005),[31] the accused persons pleaded guilty to doing seditious acts tending to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility. The acts in question were the posting of invective and pejorative anti-Malay and anti-Muslim remarks on the Internet. Given that "[r]acial and religious hostility feeds on itself",[32] such "feelings" may spread and multiply, and they need not be confined to the direct impact of the seditious act itself.

In Ong Kian Cheong, the accused persons were convicted of distributing seditious publications tending to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility, namely, evangelical tracts that promoted Protestant Christianity and denigrated Islam, and which were described as a "pointed attack by one religion on another".[33] Not only would such seditious tendencies be obvious to any reasonable man, the recipients of the tracts testified that they felt angry after reading the publications. District Judge Roy Grenville Neighbour found that the recipients' testimony "clearly proves that the publications have a seditious tendency".[33]

Between different races or classes

[edit]Section 3(1)(e) of the Sedition Act refers to promoting "feelings of ill-will and hostility between different races or classes of the population of Singapore". In contrast to the other limbs of section 3(1), which mainly aim to capture acts of subversion directed at the established government, section 3(1)(e) relates to the inflaming of ethno-religious sensitivities.[34]

However, the words races and classes have been interpreted rather loosely when applying the Sedition Act.[35] It appears that the two words are sufficiently malleable to include religious groups and cater to other types of inter-group hostility. For instance, in Ong Kian Cheong there was a tendency to conflate ethnicity with religious affiliation. This inclination to associate race with religion may stem from the fact that in Singapore, most Malays are Muslims[36] and vice versa.[37] Therefore, religious publications denigrating Islam would not only affect Muslims, but would undoubtedly cause feelings of ill-will or hostility within the Malay community as well. Also, the seditious publications distributed by the accused persons which disparaged the Roman Catholic Church and other faiths were held to have affected followers comprising "different races and classes of the population in Singapore".[36]

Academic criticism

[edit]Several academics have pointed out the weaknesses of section 3(1)(e) as a benchmark for what constitutes a seditious tendency.

Emphasis on potential harm

[edit]A literal reading of section 3(1)(e) indicates that the provision does not require proof that an act has the propensity to cause violence. In contrast, Article 149(1)(c) of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore,[38] which authorizes anti-subversion legislation, contains the additional words "likely to cause violence", which implies that section 3(1)(e) sets a lower threshold than Article 149.[39] This is consistent with how the courts have interpreted section 3(1)(e), as the cases do not address the likelihood of the seditious acts to cause harm. In other words, freedom of speech and expression is limited solely because of its potential consequences, the magnitude of which is categorically assumed.[40] However, it is arguable whether acts promoting class hatred which do not incite violence should in themselves be termed "seditious".[39]

Feelings as unreliable indicator

[edit]It is difficult to apply "feelings" as a basis for constraining speech as they are inherently subjective and difficult to measure. Furthermore, section 3(1)(e) is silent as to which audience a tendency should be evaluated by – the actual audience or an audience of "reasonable persons".[41] The same deed may produce different "feelings" depending on the temperament of the audience, as "language which would be innocuous, practically speaking if used to an assembly of professors or divines, might produce a different result if used before an excited audience of young and uneducated men".[42] Due to such ambiguity, people are left without clear guidelines as to what constitutes a seditious tendency, which may result in the chilling of free speech.[40]

Another criticism is the risk that courts may place too much emphasis on subjective feelings, which may not be a reliable basis for restricting free speech. If a subjective test is adopted, people who wish to express views on racial and religious issues may find themselves held hostage to segments of the population who may be oversensitive and more prone to finding offence than others. Hence, District Judge Neighbour's reliance in Ong Kian Cheong on the testimonies of a police officer and recipients of the tracts[33] has been criticized as "highly problematic", and it has been suggested that an objective test needs to be adopted to determine if an act will be offensive to other races or classes.[43]

Defences

[edit]Acts done without accused person's knowledge

[edit]Where allegedly seditious publications are concerned, section 6(2) of the Sedition Act provides that "[n]o person shall be convicted of any offence referred to in section 4(1)(c) or (d) if such person proves that the publication in respect of which he is charged was printed, published, sold, offered for sale, distributed, reproduced or imported (as the case may be) without his authority, consent and knowledge and without any want of due care or caution on his part or that he did not know and had no reason to believe that the publication had a seditious tendency."[44]

A plain reading of the provision suggests that there are two disjunctive limbs, such that to avail himself of section 6(2) an accused needs only to prove:

- either that the publication was distributed "without his authority, consent and knowledge and without any want of due care or caution on his part"; or

- "he did not know and had no reason to believe that the publication had a seditious tendency".

The second limb of section 6(2) was examined by District Judge Neighbour in Ong Kian Cheong. The issue in the case was whether the accused persons had knowledge or reason to believe that the publications possessed seditious tendencies.[45] The first accused claimed he did not read the tracts and thus did not know that they had seditious tendencies. He alleged that all he did was to post the tracts after the second accused had prepared them. The second accused claimed that she had purchased and distributed the tracts without reading them and had no reason to believe the publications were seditious or objectionable because they were freely available on sale in local bookstores.[46]

District Judge Neighbour, referring to the Court of Appeal's judgment in Tan Kiam Peng v. Public Prosecutor (2008),[47] held that the requirement of knowledge is satisfied if wilful blindness can be proved, as wilful blindness is, in law, a form of actual knowledge. To establish wilful blindness, a person concerned must have a clear suspicion that something is amiss, but nonetheless makes a deliberate decision not to make further inquiries in order to avoid confirming what the actual situation is.[48]

The District Judge took into account the following facts to conclude that both the accused persons had been wilfully blind to the seditious contents of the publications:

- Both accused persons were aware that something was amiss with the consignment of tracts when it was detained by the Media Development Authority (MDA). In fact, the second accused had been formally informed by the MDA that the publications she ordered were detained for being undesirable or objectionable. However, despite "having their suspicions firmly grounded", and having every opportunity to examine the publications, they "made a conscious and deliberate decision not to investigate further".[49]

- Both accused persons made no effort to surrender the offending publications, to ascertain from the MDA why the publications were objectionable, or to take other publications in their possession to the MDA to determine whether they were also objectionable.[49]

- Even though the offending tracts were available for sale to the public in a bookstore, the MDA informs importers to refer doubtful publications it, and importers have access to MDA's database to determine whether a publication is objectionable. There was no evidence that the accused persons did either of these things.[33]

- Since both the accused persons read some tracts after they ordered them, they would have known that the tracts had seditious tendencies. The tracts were easy to read and a quick flip through them would easily give the reader a gist of their message.[50]

- It was difficult to believe that in their fervour to spread the gospel truth, both accused persons did not read the publications. The titles were sufficiently arousing for someone to at least flip through their contents. Furthermore, given that the accused persons consciously undertook this evangelical exercise to convert persons of other faiths, they must have known the contents of the tracts they were distributing.[51]

Accordingly, the accused persons could not avail themselves of the defence in section 6(2).[52]

District Judge Neighbour's judgment has been criticized on the basis that his conclusions that the tracts were objectionable and that the accused persons knew about the seditious contents of the tracts were insufficient to fulfil the standard of proof.[53] The High Court in Koh Hak Boon v. Public Prosecutor (1993)[54] established that "the court must assume the position of the actual individual involved (i.e. including his knowledge and experience) [subjective inquiry], but must reason (i.e. infer from the facts known to such individual) from that position like an objective reasonable man [objective inquiry]".[53] However, instead of applying this test, District Judge Neighbour simply asserted that the accused persons must have known and/or had reason to believe that the tracts were objectionable and had a seditious tendency.[53]

There is also a suggestion that the religious doctrine held by the accused persons was relevant to the issue of whether the content was objectionable or seditious. If the accused persons had religious beliefs similar to that of the tracts' author, it would have been unlikely that reasonable individuals in the position of the accused persons would have thought that the content was objectionable or seditious.[55]

Innocent receipt

[edit]Section 7 of the Sedition Act provides that a person who is sent any seditious publication without his or her "knowledge or privity" is not liable for possession of the publication if he or she "forthwith as soon as the nature of its contents has become known" hands it to the police. However, when a person is charged with possession, the court will presume until the contrary is proved that the person knew the contents of the publication when it first came into his or her possession.[56]

Sentencing considerations

[edit]In Koh Song Huat Benjamin, the District Court held that a conviction under section 4(1)(a) of the Sedition Act will be met with a sentence that promotes general deterrence.[57] Similarly, in Ong Kian Cheong District Judge Neighbour relied on Justice V. K. Rajah's statement in Public Prosecutor v. Law Aik Meng (2007)[58] that there are many situations where general deterrence assumes significance and relevance, and one of them is offences involving community and/or race relations.[59]

Senior District Judge Richard Magnus noted in Koh Song Huat Benjamin the appropriateness of a custodial sentence for such an offence. The judge took the view that a section 4(1)(a) offence is malum in se (inherently wrong), and alluded to "the especial sensitivity of racial and religious issues in our multicultural society", in view of the Maria Hertogh incident in the 1950s and the 1964 race riots, as well as the "current domestic and international security climate".[32] He also apparently recognized the educative potential of a prison sentence. Even though the prosecution had only urged for the maximum fine permitted under the law to be imposed on one of the accused persons, his Honour felt that a nominal one-day imprisonment was also necessary to signify the seriousness of the offence. Nonetheless, he cautioned that the court would not hesitate to impose stiffer sentences in future cases where appropriate.[60]

Senior District Judge Magnus equated the moral culpability of the offender with the offensiveness of the materials.[61] As such, the first accused's "particularly vile remarks", which had provoked a widespread and virulent response and sparked off the slinging of racial slurs at Chinese and Malays, was taken to be an aggravating factor.[62] The Senior District Judge also took into account mitigating factors specific to the case – the offending acts by the accused persons were halted early on, and they had taken action to reduce the offensiveness of the acts. One of the accused persons issued an apology and removed the offending material from public access, while the other locked the discussion thread containing the offending statement and also tendered a written apology.[63] The significance of these mitigating factors was downplayed in Ong Kian Cheong, District Judge Neighbour observing that despite their presence the offences committed were serious in that they had the capacity to undermine and erode racial and religious harmony in Singapore.[64]

In Ong Kian Cheong, District Judge Neighbour stated that while people may have a desire to profess and spread their faith, the right to propagate such opinions cannot be unfettered. He found that both the accused persons, by distributing the seditious and objectionable tracts to Muslims and the general public, clearly reflected their intolerance, insensitivity and ignorance of delicate issues concerning race and religion in Singapore's multiracial and multi-religious society. Furthermore, in distributing the seditious and offensive tracts to spread their faith, the accused persons used the postal service to achieve their purpose and so were shielded by anonymity until the time they were apprehended. There is no doubt that this must have made it difficult for the police to trace them. In view of these circumstances, his Honour found that custodial sentences were warranted for both accused persons.[65]

One academic has, however, suggested that rather than invoke legal sanctions, offensive speech of this nature should just be ignored. This is because legal sanctions chill free speech, which is a social good. Furthermore, complaining about wounding speech fuels inter-class hostility and ill-will and generates a culture of escalating complaints and counter-complaints, resulting in a further net loss of speech.[66]

Suppression of seditious publications

[edit]After a person has been convicted of publishing matters having a seditious tendency in a newspaper, the court has power either in lieu of or in addition to any punishment, to make the following orders having effect for not more than a year:[67]

- Prohibiting the future publication of the newspaper.

- Prohibiting the publisher, proprietor or editor of the newspaper from "publishing, editing or writing for any newspaper or from assisting, whether with money or money's worth, material, personal service or otherwise in the publication, editing or production of any newspaper".

- Ordering that the printing press used to produce the newspaper be seized and detained by the police, or that it only be used on specified conditions.

Contravention of any order made can be punished as a contempt of court, or as a criminal offence having a maximum sentence of a fine not exceeding $5,000 or jail of up to three years or both. However, no one may be punished twice for the same offence.[68]

If the Public Prosecutor applies to the High Court[69] and shows that "the issue or circulation of a seditious publication is or if commenced or continued would be likely to lead to unlawful violence or appears to have the object of promoting feelings of hostility between different classes or races of the community", the Court is required to issue an order "prohibiting the issuing and circulation of that publication ... and requiring every person having any copy of the prohibited publication in his possession, power or control forthwith to deliver every such copy into the custody of the police".[70] It is an offence to fail to deliver a prohibited publication to a police officer on being served a prohibition order, or if it comes to one's knowledge that he or she has a prohibited publication in his or her possession, power or control. The punishment is a fine of up to $1,000 or jail for up to one year or both.[71]

The High Court can issue a warrant authorizing a police officer not below the rank of sergeant to enter and search any specified premises, to seize any prohibited publications found, and to use necessary force in doing so. Copies of the prohibition order and search warrant must be left in a "conspicuous position" in the premises entered.[72] The owner of a prohibited publication which has been seized by or delivered to the police can apply to the Court within 14 days for the prohibition order to be discharged and the return of the publications if he or she believes the order to have been improperly made.[73]

The above powers for suppressing seditious publications were introduced in the Sedition Ordinance 1948 of Malaysia. As regards the power to prevent a publication's circulation, at the time of its introduction the Acting Attorney-General of the Federation of Malaya said that it was intended to "give the court that power which exists now on the civil side of the Court – to issue an injunction against the perpetuation and dissemination of libel". The Public Prosecutor could, of course, bring a criminal charge against someone for circulating a seditious publication, but the new power was desirable as "in the meantime the harm that is being done by this thing being publishing and circulated all round the country, if not stopped, would be very much mitigated ... No time is wasted in stopping the dissemination of the libel, and that, I suggest, particularly at this juncture, is a very important condition."[4]

The Sedition Act and free speech

[edit]Interpretation of Article 14 of the Constitution

[edit]

The Sedition Act is a significant restriction on the right to freedom of speech and expression guaranteed to Singapore citizens by Article 14 of the Constitution. Article 14(2)(a) states that Parliament may by law impose restrictions on this right where it is necessary or expedient in the interest of, among other things, the security of Singapore or public order. In Chee Siok Chin v. Minister for Home Affairs (2005),[74] in which the constitutionality of provisions of the Miscellaneous Offences (Public Order and Nuisance) Act ("MOA")[75] was considered, the High Court held it was sufficient that Parliament had "considered" and "intended" to impose restrictions on freedom of speech that were necessary or expedient to ensure public order through the MOA. The Court did not undertake any separate inquiry into the necessity or expediency of the impugned restrictions in determining whether the MOA's constitutionality could be sustained.[76] Furthermore, since Article 14(2) permits restrictions "in the interests of" rather than "for the maintenance of" public order, this authorizes Parliament to take a pre-emptive or "prophylactic approach" to crafting restrictive laws which may not address the immediate or direct maintenance of public order.[77] The Sedition Act is an example of such a restrictive law and the court is entitled to interpret it as such, showing little balancing of the interest in protecting free speech against other public interests.[78]

It has been suggested that the approach taken in Chee Siok Chin towards Article 14 goes against the venerable tradition of limited government and constitutional supremacy enshrined in Article 4 of the Constitution, and accords too much deference to the legislative and executive branches of government. Moreover, the phrase necessary or expedient arguably should not be interpreted disjunctively, which would only require the State to show that a restriction imposed by Parliament is either "necessary" or "expedient". Since expedience is easily satisfied, this allows for too lenient a standard of judicial review. Such a reading would make the word necessary redundant, which goes against the well-known rule that every word in an enactment must be given meaning. Furthermore, it would undermine the value of the word right in Article 14.[79]

In Ong Kian Cheong, the accused persons argued that in order for section 3(1)(e) of the Sedition Act to "conform" with Article 14(2), it had to be read as if it contained the words productive of public disturbance or disorder or with the effect of producing public disorder. Put another way, the offence of distributing a seditious publication[80] that promoted feelings of ill-will and hostility between different races or classes of the population of Singapore would only be consistent with the right to free speech if it was limited to actions expressly or impliedly inciting public disorder.[46] Without analysing Article 14(2) or factors such as the gravity of the threat to public order, the likelihood of disorder occurring, the speaker's intent, or the reasonableness of the audience, the District Court disagreed with this submission. It stated:[29]

It is clear that if Parliament had intended to include the additional requirement for a seditious tendency to be directed against the maintenance of government it would have expressly legislated to that effect in the SA. ... I agree with the prosecution's argument that the provisions of the SA should be given a plain and literal interpretation. There is no requirement in the section that proof of sedition requires intent to endanger the maintenance of the government. It would be clearly wrong to input such intent into the section. All that is needed to be proved is that the publication is question had a tendency to promote feelings of ill will and hostility between different races or classes of the population in Singapore.

It has been argued that expediency may the correct standard for seditious speech that inflicts injury.[81] However, it is rare that seditious speech only inflicts injury without any contribution to public discourse.[82] Hence, restrictions of such speech should be held to the higher standard of necessity in the interests of one of the stated objectives in Article 14(2). In other words, the State must discharge a higher burden of proof before it can lawfully regulate seditious speech which has a "political" element. The Sedition Act, in prohibiting speech based upon mere proof of a "seditious tendency" regardless of the actual risks posed to public order, would not be in line with this proposed interpretation.[83]

As the Koh Song Huat Benjamin and Ong Kian Cheong cases involved statements that offended Malays or Muslims, this may demonstrate a greater solicitude for the sensitivities of Malays in Singapore who are predominantly Muslims. On the other hand, individuals who made racist comments against Indians and offensive cartoons against Jesus Christ were let off with only a police warning for flouting the Sedition Act.[84] It has been said it is a matter of speculation whether this reflects geopolitical realities or the Government's discharge of its duty under Article 152(2) of the Constitution to protect the interests of Malays and their religion as the indigenous people of Singapore.[85]

Prioritization of other values over free speech

[edit]Professor Thio Li-ann has expressed the opinion that in Singapore free speech is not a primary right, but is qualified by public order considerations couched in terms of "racial and religious harmony".[86] It seems that the legal framework prefers to serve foundational commitments such as the harmonious co-existence of different ethnic and religious communities,[87] because "community or racial harmony form the bedrock upon which peace and progress in Singapore are founded".[88][89] In his 2009 National Day Rally speech, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong characterized racial and religious divides as "the most visceral and dangerous fault line" in Singapore society,[90] and earlier he had said that "we must respect one another's religions, we must not deliberately insult or desecrate what others hold sacred because if we want to live peacefully together, then we must live and let live, there must be tolerance, there must be mutual respect".[91]

In Ong Kian Cheong, District Judge Neighbour did not treat free speech in the form of seditious speech as trumping the competing interests of ensuring freedom from offence, as well as protecting social harmony between ethnic and religious groups. He approved the view that offences involving community and/or race relations warrant general deterrence.[88] Furthermore, the judge did not deem the right of religious propagation guaranteed by Article 15(1) of the Constitution a mitigating factor because the accused persons, as Singaporeans, could not claim ignorance of the sensitive nature of race and religion in multiracial and multi-religious Singapore.[92]

Other statutes

[edit]There is an "intricate latticework of legislation" in Singapore to curb public disorder, which arguably gives effect to Parliament's intent to configure an overlapping array of arrangements,[93] and to leave the choice of a suitable response to prosecutorial discretion.[94]

Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act

[edit]The Sedition Act plays its part by criminalizing the doing of any act or the uttering of any words having a seditious tendency, and dealings with seditious publications. The Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act ("MRHA")[95] is another piece of this legislative jigsaw. It was introduced to ensure that adherents of different religious groups exercise tolerance and moderation, and to keep religion out of politics. Minister for Home Affairs S. Jayakumar stated that the MRHA takes a pre-emptive approach and can be invoked in a restrained manner to enable prompt and effective action.[96] In contrast with the punitive approach of the Sedition Act where a breach of the statute carries criminal liability, under the MRHA restraining orders may be imposed upon people causing feelings of enmity, hatred, ill-will or hostility between different religious groups, among other things.[97] Criminal sanctions only apply if such orders are contravened.[98]

While the MRHA is meant to efficiently quell mischief of a religious nature,[99] the Sedition Act encompasses a broader category of mischief. A plain reading suggests that section 3 of the Sedition Act governs racial and class activities. However, it has been argued that the mischief of the MRHA is subsumed under the Sedition Act. This is because in Koh Song Huat Benjamin, Senior District Judge Magnus employed the phrases "anti-Muslim" and "anti-Malay" interchangeably and suggested that the Sedition Act governs acts which connote anti-religious sentiments. Unlike the Sedition Act, the MRHA excludes the word "tendency", which means there must be evidence that the person has "committed" or "is attempting to commit" an act that harms religious harmony, instead of having a mere tendency cause such harm.[100]

Penal Code, section 298A

[edit]Another statutory counterpart to the Sedition Act is section 298A of the Penal Code,[101] which was introduced in 2007 to "criminalise the deliberate promotion by someone of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different racial and religious groups on grounds of race or religion".[94] Unlike the Sedition Act, section 298A includes the additional requirement of knowledge,[102] and excludes a proviso which decriminalizes certain bona fide acts. Nonetheless, even though section 298A is regarded as an alternative to the Sedition Act, it has been proposed that the law should make clearer when section 298A, instead of the Sedition Act, should be employed.[103]

Proposal for legislation for inter-group antagonism

[edit]Currently, the Sedition Act has both "vertical" and "horizontal" dimensions. The Act has vertical effect in that it criminalizes statements which incites violence against government institutions, and horizontal effect because it criminalizes statements which harm the relationships between sectors of the community.[104] Professor Thio has argued that the Sedition Act should be reserved for politically motivated incitements of violence which threaten the life of the state and its institutions, and that public order problems of feelings of ill-will and hostility between different races or classes should not be prosecuted under the umbrella of sedition. In other words, the vertical aspect of sedition should be retained, but there should be separate legislation for the horizontal aspect. Such a separate statutory provision could set out precise norms to regulate harmful non-political forms of speech with the goal of managing ethnic relations and promoting national identity. This would bring clarity to the underlying free speech theories involved.[105] The proposal is supported by the view of Professor Tan Yock Lin that when construing section 3(1)(e) in the light of the preceding four limbs, it could only have been intended to embody one of the many forms of seditious libel and must be construed so as to require proof of defiance of constituted authority.[27]

Notable uses of sedition laws

[edit]

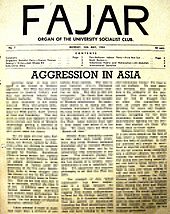

On or about 10 May 1954, the University Socialist Club of the University of Malaya in Singapore published issue 7 of the Club's newsletter Fajar ("Dawn" in Malay). Eight students involved in the publication were charged under the Sedition Ordinance 1938 (S.S.) with possessing and distributing the newsletter, which was claimed to contain seditious articles that criticized the British colonial government. The students included Poh Soo Kai, James Puthucheary and Edwin Thumboo. They were represented by Lee Kuan Yew and Denis Nowell Pritt, Q.C. On 25 August, following a two-and-a-half-day trial, the First Criminal District Court accepted Pritt's submission of no case to answer. The judge, Frederick Arthur Chua, ruled that the newsletter was not seditious and acquitted the students.[106]

Two Barisan Sosialis Members of Parliament, Chia Thye Poh and Koo Young, were charged with sedition after publishing the 11 December 1965 issue of the Chern Sien Pau, the Chinese edition of the party organ The Barisan, which claimed that the People's Action Party government was "plotting to murder" Lim Chin Siong, a left-wing politician who had founded the Barisan Sosialis.[107] On 26 July 1966, the defendants were found guilty and sentenced to a fine of $2,000 each. They appealed against their convictions but subsequently withdrew the appeals.[108]

The first convictions under the Sedition Act since the 1960s took place in October 2005, and involved two men, Benjamin Koh and Nicholas Lim, who pleaded guilty to charges under section 4(1)(a) for making anti-Malay and anti-Muslim remarks on the Internet in response to a letter published in The Straits Times on 14 July 2005.[109] In the letter, a Muslim woman asked if taxi companies allowed uncaged pets to be transported in taxis, as she had seen a dog standing on a taxi seat next to its owner. She said that "dogs may drool on the seats or dirty them with their paws".[110] Her concerns had a religious basis as, according to Ustaz Ali Haji Mohamed, chairman of Khadijah Mosque: "There are various Islamic schools of thought which differ in views. But most Muslims in Singapore are from the Shafi'i school of thought. This means they are not allowed to touch dogs which are wet, which would include a dog's saliva. This is a religious requirement."[109] In the judgment entitled Public Prosecutor v. Koh Song Huat Benjamin,[31] Senior District Judge Magnus sentenced Koh to one month's imprisonment as he found the statements Koh made to have been "particularly vile" – among other things, Koh had placed the halal logo of the Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (Islamic Religious Council of Singapore) next to a picture of a pig's head, mocked Muslim customs and beliefs, and compared Islam to Satanism.[111] As Lim's statements were not as serious, he was sentenced to one day in jail and the maximum fine of $5,000.[112]

A third person, a 17-year-old youth named Gan Huai Shi, was also charged under the Sedition Act for posting a series of offensive comments about Malays on his blog entitled The Second Holocaust between April and July 2005.[113] Gan pleaded guilty to two counts of sedition, and on 23 November 2005 he was granted 24 months' supervised probation that included counselling sessions and service in the Malay community.[114] In June 2006, a 21-year-old blogger who used the moniker "Char" was investigated by the police for posting offensive cartoons of Jesus Christ on his blog.[115] He was let off with a stern warning.[116]

The case of Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong[28] involved a middle-aged Christian couple, Ong Kian Cheong and Dorothy Chan, who were charged with possessing and distributing seditious publications contrary to the Sedition Act, and distributing objectionable publications contrary to the Undesirable Publications Act.[117] The works were tracts by Chick Publications which the couple had posted to Muslims,[118] and the charges alleged that the tracts had the tendency to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between Christians and Muslims.[119] Following a trial, the couple were found guilty[120] and sentenced on 6 August 2009 to eight weeks' jail each.[121]

In 2015, the Sedition Act was invoked in respect of two separate incidents. On 7 April, a Filipino nurse named Ello Ed Mundsel Bello was charged with posting comments on Facebook on 2 January that had a tendency to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between Filipinos and Singaporeans. In one post he allegedly called Singaporeans "loosers" (losers) and vowed to "evict" them from the country. He prayed that "disators" (disasters) would strike Singapore, and that he would celebrate when "more Singaporeans will die". The post concluded, "Pinoy better and stronger than Stinkaporeans". In another post made later that day, he said he would "kick out all Singaporeans" and that the country would be a new "filipino state" [sic].[122] Bello pleaded guilty to the charge and was sentenced to three months' jail for the seditious statements, and another month for lying to police investigators.[123]

On 14 April a couple, a Singaporean man named Yang Kaiheng and an Australian woman named Ai Takagi, were charged with seven counts of posting on a website operated by them called The Real Singapore a number of articles that could lead to ill-will and hostility between Singaporeans and foreigners. These included an untrue story about a Filipino family who had supposedly provoked an incident between participants of the annual Thaipusam procession and the police by complaining about musical instruments being played during the event, and a claim that Filipinos living in Singapore were favouring fellow citizens to the detriment of Singaporeans. They were the last person to be charged for sedition in Singapore before the law is repealed in 2021.[124] On 3 May 2015 The Real Singapore website was disabled after the MDA suspended the statutory class licence applicable to the site and ordered its editors to cease operating it.[125] Ai pleaded guilty and was sentenced to ten months' imprisonment in March 2016. Yang claimed trial and was also convicted; he was sentenced in June 2016 to eight months' imprisonment.[126]

Developments in other jurisdictions

[edit]

Following the abolition of the common law offences of sedition and seditious libel in the United Kingdom by section 73 of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009,[127] there has been mounting civil society pressure for Commonwealth countries including Malaysia and India to repeal their sedition laws. In July 2012, Malaysia's Prime Minister Najib Razak announced plans to repeal the Sedition Act 1948.[128] However, at the 2014 general assembly of his political party, the United Malays National Organisation, he announced a reversal of this policy. At an event in March 2015 he said, "We should not be apologetic. Some may say this is not democratic, this [violates] rights to freedom, and more, but I want to say that there is no absolute freedom. There is no place for absolute freedom without responsibility in this country."[129] On 10 April 2015, following a 12-hour parliamentary debate, the Sedition (Amendment) Act 2015 was enacted. Changes to the law included clarifying that calling for secession and promoting feelings of ill-will, hostility and hatred between people or groups of people on religious grounds amount to sedition; empowering the Public Prosecutor to call for bail to be denied to persons charged with sedition and for them to be prevented from leaving the country; introducing a minimum jail term of three years and extending the maximum term to 20 years; and enabling the courts to order that seditious material on the Internet be taken down or blocked. On the other hand, criticizing the government is no longer an offence.[130]

The Malaysian Act was amended while a decision by the Federal Court on whether the Act violated the right to freedom of speech guaranteed by Article 10 of the Constitution of Malaysia was pending.[131] The case was brought by Dr. Azmi Sharom, a law professor from the University of Malaya who had been charged with sedition[132] for comments he made on the 2009 Perak constitutional crisis which were published on the website of The Malay Mail on 14 August 2014.[133] On 6 October, the Federal Court ruled that the provision of the Sedition Act challenged was not unconstitutional. Azmi will therefore stand trial on the original charge.[134]

See also

[edit]- Article 14 of the Constitution of Singapore

- Censorship in Singapore

- Criminal law of Singapore

- Sedition

- Sedition Act (Malaysia)

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Sedition Ordinance 1948 (No. 14 of 1958, Malaya), now the Sedition Act 1948 (Act 15, 2006 Reprint, Malaysia), archived from the original on 4 April 2015.

- ^ The Malaysian Act extended to Sabah on 28 May 1964 (Modification of Laws (Sedition) (Extension and Modification) Order 1964 (Legal Notification (L.N.) 149/64)), and to Sarawak on 20 November 1969 (Modification of Laws (Sedition) (Extension and Modification) Order 1969 (P.U.(A) 476/69)). (P.U. is an abbreviation for Pemberitahu Undangan, which is Malay for "Legislative Notification".)

- ^ "Legislative History Sedition Act (Chapter 290)". Singapore Statutes Online. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "The Sedition Bill, 1948", Official Report of the Proceedings of the Legislative Council (F.S. 10404/48, 6 July 1948): Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Federation of Malaya for the Period (First Session) February, 1948, to February, 1949 with Appendix, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Printed at the Government Press by H. T. Ross, Government Printer, 1951, pp. B351 – B353, OCLC 225372680.

- ^ "Commencement of the Sedition (Repeal) Act 2021". Ministry of Home Affairs. 1 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Thio Li-ann (2012), "Freedom of Speech, Assembly and Association", A Treatise on Singapore Constitutional Law, Singapore: Academy Publishing, pp. 747–867 at p. 775, para. 14.061, ISBN 978-981-07-1516-8.

- ^ The Case De Libellis Famosis, or of Scandalous Libels (1572) (1606) 5 Co. Rep. [Coke's King Bench Reports] 125a, 77 E.R. 250, King's Bench (England).

- ^ James H. Landman (Winter 2002), "Trying Beliefs: The Law of Cultural Orthodoxy and Dissent", Insights on Law and Society, American Bar Association, 2 (2), archived from the original on 17 April 2015, retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ R. v. Chief Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate, ex parte Choudhury [1991] 1 Q.B. 429, High Court (Queen's Bench) (England and Wales).

- ^ Clare Feikert-Ahalt (2 October 2012), Sedition in England: The Abolition of a Law from a Bygone Era, In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress, Library of Congress, archived from the original on 24 March 2015.

- ^ Tan Yock Lin (2011), "Sedition and Its New Clothes in Singapore", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 212–236 at 212, SSRN 1965870.

- ^ Ex parte Choudhury, p. 453.

- ^ Sedition Ordinance 1938 (No. 18 of 1938, Straits Settlements).

- ^ a b c See Jaclyn Ling-Chien Neo (2011), "Seditious in Singapore! Free Speech and the Offence of Promoting Ill-will and Hostility between Different Racial Groups" (PDF), Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 351–372 at 353, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2015.

- ^ Sedition Enactment 1939 (No. 13 of 1939, Federated Malay States).

- ^ a b Sedition Act (Cap. 290, 1985 Rev. Ed.) ("SA").

- ^ "Bill to repeal Sedition Act introduced in Parliament; its application is 'limited' given overlaps with other laws: MHA". 13 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Parliament repeals Sedition Act, amends Penal Code and Criminal Procedure Code to cover relevant aspects". 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Sedition (Repeal) Act 2021 2021 (No. 30 of 2021)

- ^ Sedition (Repeal) Act 2021 (Commencement) Notification 2022 2022 (S 867/2022)

- ^ SA, s. 4.

- ^ SA, s. 6(1).

- ^ SA, s. 2 (definition of seditious).

- ^ Thio, p. 778, para. 14.065.

- ^ SA, s. 3(3).

- ^ Tan, p. 225.

- ^ a b Tan, p. 228.

- ^ a b Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong [2009] SGDC 163, District Court (Singapore), archived from the original on 17 April 2015. For commentary, see Thio Li-ann (2009), "Administrative and Constitutional Law" (PDF), Singapore Academy of Law Annual Review of Singapore Cases, 10: 1–37 at 12–17, paras. 1.28–1.39, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2015.

- ^ a b Ong Kian Cheong, para. 47.

- ^ Thio, p. 778, paras. 14.071–14.072.

- ^ a b Public Prosecutor v. Koh Song Huat Benjamin [2005] SGDC 272, D.C. (Singapore). For commentary, see Thio Li-ann (2005), "Administrative and Constitutional Law" (PDF), Singapore Academy of Law Annual Review of Singapore Cases, 6: 1–38 at 17–20, paras. 1.43–1.48, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2015.

- ^ a b Koh Song Huat Benjamin, para. 6.

- ^ a b c d Ong Kian Cheong, para. 59.

- ^ Zhong Zewei (2009), "Racial and Religious Hate Speech in Singapore: Management, Democracy, and the Victim's Perspective", Singapore Law Review, 27: 13–59 at 16, SSRN 1418654.

- ^ Thio, p. 787, para. 14.088.

- ^ a b Ong Kian Cheong, para. 77.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, para. 48.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1985 Rev. Ed., 1999 Reprint).

- ^ a b Thio, p. 779, para. 14.068.

- ^ a b Thio, p. 789, para. 14.091.

- ^ Thio, p. 779, para. 14.069.

- ^ R. v. Aldred (1909) 22 Cox C.C. 1 at 3.

- ^ Neo, pp. 361–362.

- ^ SA, s. 6(2).

- ^ Ronald Wong (2011), "Evangelism And Racial-Religious Harmony: A Call To Reconsider Tolerance: Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong [2009] SGDC 163", Singapore Law Review, 29: 85–113 at 90, SSRN 2544171.

- ^ a b Ong Kian Cheong, para. 45.

- ^ Tan Kiam Peng v. Public Prosecutor [2007] SGCA 38, [2008] 1 S.L.R.(R.) [Singapore Law Reports (Reissue) 1, Court of Appeal (Singapore).

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, para. 50.

- ^ a b Ong Kian Cheong, para. 51.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, para. 61.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, para. 63.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, para. 64.

- ^ a b c Wong, p. 90.

- ^ Koh Hak Boon v. Public Prosecutor [1993] 2 S.L.R.(R.) 733, High Court (Singapore).

- ^ Wong, pp. 90–91.

- ^ SA, s. 7.

- ^ Koh Song Huat Benjamin, para. 5.

- ^ Public Prosecutor v. Law Aik Meng [2007] SGHC 33, [2007] 2 S.L.R.(R.) 814, H.C. (Singapore).

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, para. 74.

- ^ Koh Song Huat Benjamin, paras. 16–17.

- ^ Koh Song Huat Benjamin, para. 12.

- ^ Koh Song Huat Benjamin, para. 11.

- ^ Koh Song Huat Benjamin, para. 10.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, paras. 75–76.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, paras. 80–84.

- ^ Thio, p. 788, para. 14.089.

- ^ SA, s. 9(1).

- ^ SA, ss. 9(2) and (3).

- ^ SA, s. 10(9).

- ^ SA, s. 10(1).

- ^ SA, ss. 10(4) and (5).

- ^ SA, s. 10(6).

- ^ SA, s. 10(7). If no application is made within 14 days from the date of seizure or delivery of the publication, or the High Court does not order the publication to be returned to its owner, the publication is deemed to be forfeited to the Government: s. 10(8).

- ^ Chee Siok Chin v. Minister for Home Affairs [2005] SGHC 216, [2006] S.L.R.(R.) 582, H.C. (Singapore).

- ^ Miscellaneous Offences (Public Order and Nuisance) Act (Cap. 184, 1997 Rev. Ed.) ("MOA").

- ^ Chee Siok Chin, p. 604, para. 56.

- ^ Chee Siok Chin, p. 603, para. 50.

- ^ Thio, p. 789, para. 14.092.

- ^ Zhong, pp. 27–30.

- ^ SA, s. 4(1)(c).

- ^ Zhong, p. 42.

- ^ Zhong, p. 28, quoting the Supreme Court of the United States in Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343 (2003).

- ^ Zhong, p. 43.

- ^ Rachel Chang (10 February 2010), "ISD investigation not less serious than being arrested: DPM", The Straits Times (reproduced on AsiaOne), archived from the original on 14 February 2010.

- ^ Thio, p. 784, para. 14.078–14.079.

- ^ Thio, p. 783, para. 14.077.

- ^ Thio, p. 789, para. 14.090.

- ^ a b Law Aik Meng, p. 827, para. 24, cited in Ong Kian Cheong, para. 74.

- ^ Thio, p. 786, para. 14.084.

- ^ Clarissa Oon (17 August 2009), "PM warns of religious fault lines: Race and religion identified as 'most dangerous' threat to Singapore's harmony and cohesiveness", The Straits Times (reproduced on the website of Singapore United: The Community Engagement Programme, Ministry of Home Affairs), archived from the original on 18 May 2015, retrieved 19 April 2015. The full speech is available at Lee Hsien Loong (16 August 2009), National Day Rally Speech 2009, Sunday, 16 August 2009 (PDF), Singapore United: The Community Engagement Programme, Ministry of Home Affairs, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Danish cartoons provocative and wrong, says PM", The Straits Times, p. 6, 11 February 2006.

- ^ Ong Ah Chuan, para. 82.

- ^ Zhong, p. 19.

- ^ a b Ho Peng Kee (Senior Minister of State for Home Affairs), speech during the Second Reading of the Penal Code (Amendment) Bill, Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (22 October 2007), vol. 83, col. 2175ff. (section entitled "Preserving religious and racial harmony in the new global security climate").

- ^ Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (Cap. 167A, 2001 Rev. Ed.) ("MRHA").

- ^ S. Jayakumar (Minister for Home Affairs), speech during the Second Reading of the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Bill, Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (18 July 1990), vol. 56, col. 325ff.

- ^ MRHA, ss. 8 and 9.

- ^ MRHA, s. 16.

- ^ Tey Tsun Hang (2008), "Excluding Religion from Politics and Enforcing Religious Harmony – Singapore-style", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 118–142 at p. 132, archived from the original on 18 February 2017, retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Tey, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Penal Code (Cap. 224, 2008 Rev. Ed.).

- ^ Zhong, p. 28.

- ^ Tey, p. 140.

- ^ Thio, p. 787, para. 14.086.

- ^ Thio, p. 791, para. 14.097.

- ^ "Students' trial set for Aug. 10, 11: Varsity publication seditious 'as a whole' – Crown", The Straits Times, p. 7, 2 July 1954; "Sedition charges specified by Crown: The 8 varsity students get the details", The Straits Times, p. 5, 3 July 1954; "Q.C. says: Tremendous victory for freedom of speech", The Straits Times, p. 1, 26 August 1954; "A charge of sedition [editorial]", The Straits Times, p. 6, 26 August 1954; "Eight university students freed: No sedition, the judge rules", The Straits Times, p. 7, 26 August 1954. See also Poh Soo Kai; Tan Jing Quee; Koh Kay Yew, eds. (2010), The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, ISBN 978-983378287-1.

- ^ "Two Barisan leaders arrested on sedition charge: Chia Thye Poh, Koo Young picked up at party HQ", The Straits Times, p. 1, 16 April 1966; "Sedition charge not properly framed says court", The Straits Times, p. 2, 17 April 1966; "Court sets aside seven days in July for Barisan sedition trial", The Straits Times, p. 11, 1 May 1966; "The day Chin Siong tried to kill himself ...: MPs on trial on sedition charge: First day", The Straits Times, p. 9, 5 July 1966; Cheong Yip Seng (13 July 1966), "Chia makes defence on why he printed article: Sedition trial: Sixth day", The Straits Times, p. 5.

- ^ Chia Poteik; Cheong Yip Seng; Yeo Toon Joo (27 July 1966), "MPs found guilty, fined $2,000 each: Counsel gives notice of appeal", The Straits Times, p. 11; "Barisan ex-MPs withdraw appeal", The Straits Times, p. 6, 16 December 1966.

- ^ a b Chong Chee Kin (13 September 2005), "2 charged with making racist remarks on Net", The Straits Times, p. 1.

- ^ Zuraimah Mohammed (14 June 2005), "Uncaged pet seen in taxi [letter]", The Straits Times, p. 8.

- ^ Koh Song Huat Benjamin, paras. 11 and 15.

- ^ Koh Song Huat Benjamin, paras. 11 and 16.

- ^ Chong Chee Kin (17 September 2005), "Third person accused of racist comments on Net", The Straits Times, p. 2.

- ^ Third Singapore racist blogger pleads guilty to sedition, Agence France-Presse (reproduced on Singapore Window), 26 October 2005, archived from the original on 22 June 2013; Chong Chee Kin (27 October 2005), "3rd racist blogger convicted but may avoid jail term", The Straits Times, p. 1; Chong Chee Kin (24 November 2005), "Not jail, but immersion in Malay community", The Straits Times, p. 1; Vinita Ramani (24 November 2005), "An 'eye-opening' probation: Judge recommends community service with Malays for racist blogger", Today, p. 10.

- ^ Zakir Hussain (14 June 2006), "Blogger who posted cartoons of Christ online being investigated", The Straits Times, p. 1; Jesus cartoons could draw jail for Singapore blogger, Agence France-Presse (reproduced on Daily News and Analysis), 14 June 2006, archived from the original on 21 April 2015, retrieved 23 April 2015; Karen Tee (27 June 2006), "Blogosphere: Char speaks out", The Straits Times (Digital Life), p. 18.

- ^ T. Rajan (21 July 2006), "Warning for blogger who posted cartoon of Christ", The Straits Times, p. 4.

- ^ Undesirable Publications Act (Cap. 338, 1998 Rev. Ed.).

- ^ "Couple charged under Sedition Act", The Straits Times, 15 April 2008.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, para. 4.

- ^ Christian couple convicted for anti-Muslim booklets, Agence France-Presse (reproduced on AsiaOne), 29 May 2009, archived from the original on 16 February 2016, retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Ong Kian Cheong, paras. 84–86; "Duo jailed eight weeks", The Straits Times, 11 June 2009.

- ^ Filipino charged with sedition for anti-Singapore online rant, Agence France-Press (reproduced on Yahoo! News Singapore), 7 April 2015, archived from the original on 22 April 2015; Elena Chong (8 April 2015), "Filipino charged with sedition for 'anti-S'pore rant' on FB", My Paper, p. A4, archived from the original on 22 April 2015.

- ^ Stefanus Ian (21 September 2015), Singapore jails Filipino nurse for 'seditious' posts, Agence France-Press (reproduced on Yahoo! News Singapore), archived from the original on 6 October 2015.

- ^ Elena Chong (15 April 2015), "Couple behind TRS website face sedition charges", The Straits Times (reproduced on Singapore Law Watch), archived from the original on 22 April 2015; Neo Chai Chin (15 April 2015), "The Real Singapore duo charged under Sedition Act", Today, p. 1.

- ^ MDA Statement on TRS, Media Development Authority, 3 May 2015, archived from the original on 4 May 2015; Rachel Au-Yong (4 May 2015), "Socio-political site shut down on MDA's orders: The Real Singapore had published 'objectionable' material", The Straits Times, p. 1; Valerie Koh (4 May 2015), "Govt orders shutdown of The Real Singapore: Site published articles that were against national harmony: MDA", Today, pp. 1–2, archived from the original on 4 May 2015.

- ^ Pearl Lee (29 June 2016), "TRS co-founder gets eight months' jail: Yang exploited nationalistic sentiments for financial gain and not for ideology, says judge", The Straits Times, p. A4; Kelly Ng (24 June 2016), "Former TRS editor Yang Kaiheng found guilty of sedition", Today, archived from the original on 25 June 2016.

- ^ Coroners and Justice Act 2009 (c. 25 Archived 20 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, UK).

- ^ Malaysia to repeal sedition law as polls loom, Yahoo! News Singapore, 12 July 2012, archived from the original on 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Sedition Act needed to curb terror threat: Najib: Malaysian PM defends law, as critics accuse govt of using it to silence critics", Today, p. 1, 26 March 2015, archived from the original on 22 April 2015.

- ^ G. Surach; Shaik Amin; Noraizura Ahmad (10 April 2015), Sedition Act passed with slight amendments after 12-hour debate, The Rakyat Post, archived from the original on 22 April 2015; Malaysian parliament passes tough Sedition Act amendments criticised by UN, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 10 April 2015, archived from the original on 22 April 2015; "Malaysia passes changes to Sedition Act", The Straits Times, 11 April 2015; "Malaysia toughens sedition law to include online media ban", Today, p. 10, 11 April 2015, archived from the original on 22 April 2015.

- ^ Ida Lim (24 March 2015), "Sedition Act unconstitutional as it pre-dates Parliament, apex court hears", The Malay Mail, archived from the original on 22 April 2015.

- ^ Zurairi A. R. (1 September 2014), "UM law professor latest caught in Putrajaya's sedition dragnet", The Malay Mail, archived from the original on 1 September 2014.

- ^ Zurairi A. R. (14 August 2014), "Take Perak crisis route for speedy end to Selangor impasse, Pakatan told", The Malay Mail, archived from the original on 26 December 2014.

- ^ Ida Lim (6 October 2015), "Federal Court rules Sedition Act constitutional, UM's Azmi Sharom to stand trial", The Malay Mail, archived from the original on 6 October 2015.

References

[edit]Cases

[edit]- R. v. Chief Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate, ex parte Choudhury [1991] 1 Q.B. 429, High Court (Queen's Bench) (England and Wales).

- Public Prosecutor v. Koh Song Huat Benjamin [2005] SGDC 272, District Court (Singapore).

- Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong [2009] SGDC 163, D.C. (Singapore).

Legislation

[edit]- Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1985 Rev. Ed., 1999 Reprint), Article 14.

- Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (Cap. 167A, 2001 Rev. Ed.) ("MRHA").

- Sedition Act 1948 (2020 Rev. Ed) ("SA").

Other works

[edit]- Neo, Jaclyn Ling-Chien (2011), "Seditious in Singapore! Free Speech and the Offence of Promoting Ill-will and Hostility between Different Racial Groups" (PDF), Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 351–372, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2015.

- Tan, Yock Lin (2011), "Sedition and Its New Clothes in Singapore", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 212–236, SSRN 1965870.

- Tey, Tsun Hang (2008), "Excluding Religion from Politics and Enforcing Religious Harmony – Singapore-style", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 2008: 118–142.

- Thio, Li-ann (2012), "Freedom of Speech, Assembly and Association", A Treatise on Singapore Constitutional Law, Singapore: Academy Publishing, pp. 747–867, ISBN 978-981-07-1516-8.

- Wong, Ronald (2011), "Evangelism and Racial-Religious Harmony: A Call To Reconsider Tolerance: Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong [2009] SGDC 163", Singapore Law Review, 29: 85–113, SSRN 2544171.

- Zhong, Zewei (2009), "Racial and Religious Hate Speech in Singapore: Management, Democracy, and the Victim's Perspective", Singapore Law Review, 27: 13–59, SSRN 1418654.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch