Kingdom of Tlemcen

Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen مملكة تلمسان (Arabic) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1235–1556 | |||||||||||||||||

| One of the flags attributed to Zayyanid Tlemcen[a] | |||||||||||||||||

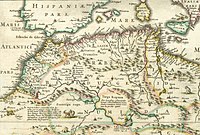

![The kingdom of Tlemcen at the beginning of the 14th century.[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Zayyanid_Kingdom_at_the_beginning_of_the_14th_century.png/250px-Zayyanid_Kingdom_at_the_beginning_of_the_14th_century.png) The kingdom of Tlemcen at the beginning of the 14th century.[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tlemcen | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Berber, Maghrebi Arabic | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||

• 1236–1283 | Abu Yahya I bin Zayyan | ||||||||||||||||

• 1318-1337 | Abu Tashufin I | ||||||||||||||||

• 1359-1389 | Abu Hammu II | ||||||||||||||||

• 1468–1504 | Abu Abdallah IV | ||||||||||||||||

• 1550–1556 | Al Hassan ben Abu Muh | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

| 1235 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1248 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1264 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1299-1307 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1329 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1337-1348 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1352-1359 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1411 | |||||||||||||||||

• Conflicts with the Spaniards | 1504–1512 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1556 | |||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

The Kingdom of Tlemcen or Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen (Arabic: الزيانيون) was a kingdom ruled by the Berber Zayyanid dynasty[3][4] in what is now the northwest of Algeria. Its territory stretched from Tlemcen to the Chelif bend and Algiers, and at its zenith reached Sijilmasa and the Moulouya River in the west, Tuat to the south and the Soummam in the east.[5][6][7]

The Tlemcen Kingdom was established after the demise of the Almohad Caliphate in 1236, and later fell under Ottoman rule in 1554. The capital of the kingdom was Tlemcen, which lay on the primary east–west route between Morocco and Ifriqiya. The kingdom was situated between the realm of the Marinids to the west, centred on Fez, and the Hafsids to the east, centred on Tunis.

Tlemcen was a hub for the north–south trade route from Oran on the Mediterranean coast to the Western Sudan. As a prosperous trading centre, it attracted its more powerful neighbours. At different times the kingdom was invaded and occupied by the Marinids from the west,[8] by the Hafsids from the east, and by Aragonese from the north. At other times, they were able to take advantage of turmoil among their neighbours: during the reign of Abu Tashfin I (r. 1318–1337) the Zayyanids occupied Tunis and in 1423, under the reign of Abu Malek, they briefly captured Fez.[9][10]: 287 In the south the Zayyanid realm included the Tuat, Tamentit, and Draa regions which was governed by Abdallah Ibn Moslem ez Zerdali, a sheikh of the Zayyanids.[11][12][5]

History

[edit]Rise to power (13th century)

[edit]The Bānu ʿabd āl-Wād, also called the Bānu Ziyān or Zayyanids after Yaghmurasen Ibn Zyan, the founder of the dynasty, were a Berber clan who had long been settled in the Central Maghreb. Although contemporary chroniclers asserted that they had a noble Arab origin, Ibn Zayyan reportedly spoke in Zenati dialect and denied the lineage that genealogists had attributed to him.[13][14][15] Yaghmurasen would in fact have responded yessen rabi, which means in Berber "god only knows", to this claim.[16] The town of Tlemcen, called Pomaria by the Romans, is about 806m above sea level in fertile, well-watered country.[17]

Tlemcen was an important centre under the Almoravid dynasty and its successors the Almohad Caliphate, who began a new wall around the town in 1161.[18]

Ibn Zayyan was governor of Tlemcen under the Almohads.[19] He inherited leadership of the family from his brother in 1235.[20] When the Almohad empire began to fall apart, in 1235, Yaghmurasen declared his independence.[19] The city of Tlemcen became the capital of one of three successor states, ruled for centuries by successive Ziyyanid sultans.[21] Its flag was a white crescent pointing upwards on a blue field.[22] The kingdom covered the less fertile regions of the Tell Atlas. Its people included a minority of settled farmers and villagers, and a majority of nomadic herders.[19]

Yaghmurasen was able to maintain control over the rival Berber groups, and when faced with the outside threat of the Marinid dynasty, he formed an alliance with the Emir of Granada and the King of Castile, Alfonso X.[23] According to Ibn Khaldun, "he was the bravest, most dreaded and honourable man of the 'Abd-la-Wadid family. No one looked after the interest of his people, maintained the influence of the kingdom and managed the state administration better than he did."[20] In 1248 he defeated the Almohad Caliph in the Battle of Oujda during which the Almohad Caliph was killed. In 1264 he managed to conquer Sijilmasa, therefore bringing Sijilmasa and Tlemcen, the two most important outlets for trans-Saharan trade under one authority.[24][25] Sijilmasa remained under his control for 11 years.[26] Before his death he instructed his son and heir Uthman to remain on the defensive with the Marinid kingdom, but to expand into Hafsid territory if possible.[20]

14th century

[edit]For most of its history the kingdom was on the defensive, threatened by stronger states to the east and the west. The nomadic Arabs to the south also took advantage of the frequent periods of weakness to raid the centre and take control of pastures in the south.

The city of Tlemcen was several times attacked or besieged by the Marinids, and large parts of the kingdom were occupied by them for several decades in the fourteenth century.[19]

The Marinid Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr besieged Tlemcen from 1299 to 1307. During the siege he built a new town, al-Mansura, diverting most of the trade to this town.[28] The new city was fortified and had a mosque, baths and palaces. The siege was raised when Abu Yakub was murdered in his sleep by one of his eunuchs.[9]

When the Marinids left in 1307, the Zayyanids promptly destroyed al-Mansura.[28] The Zayyanid king Abu Zayyan I died in 1308 and was succeeded by Abu Hammu I (r. 1308–1318). Abu Hammu was later killed in a conspiracy instigated by his son and heir Abu Tashufin I (r. 1318–1337). The reigns of Abu Hammu I and Abu Tashufin I marked the second apogee of the Zayyanids, a period during which they consolidated their hegemony in the central Maghreb.[26] Tlemcen recovered its trade and its population grew, reaching about 100,000 by around the 1330s.[28] Abu Tashufin initiated hostilities against Ifriqiya while the Marinids were distracted by their internal struggles. He besieged Béjaïa and sent an army into Tunisia that defeated the Hafsid king Abu Yahya Abu Bakr II, who fled to Constantine while the Zayyanids occupied Tunis in 1325.[9][29][30]

The Marinid sultan Abu al-Hasan (r. 1331–1348) cemented an alliance with Hafsids by marrying a Hafsid princess. Upon being attacked by the Zayyanids again, the Hafsids appealed to Abu al-Hasan for help, providing him with an excuse to invade his neighbour.[31] The Marinid sultan initiated a siege of Tlemcen in 1335 and the city fell in 1337.[28] Abu Tashufin died during the fighting.[9] Abu al-Hasan received delegates from Egypt, Granada, Tunis and Mali congratulating him on his victory, by which he had gained complete control of the trans-Saharan trade.[31] In 1346 the Hafsid Sultan, Abu Bakr, died and a dispute over the succession ensued. In 1347 Abu al-Hasan annexed Ifriqiya, briefly reuniting the Maghrib territories as they had been under the Almohads.[32]

However, Abu al-Hasan went too far in attempting to impose more authority over the Arab tribes, who revolted and in April 1348 defeated his army near Kairouan. His son, Abu Inan Faris, who had been serving as governor of Tlemcen, returned to Fez and declared that he was sultan. Tlemcen and the central Maghreb revolted.[32] The Zayyanid Abu Thabit I (1348–1352) was proclaimed king of Tlemcen.[9] Abu al-Hasan had to return from Ifriqiya by sea. After failing to retake Tlemcen and being defeated by his son, Abu al-Hasan died in May 1351.[32] In 1352 Abu Inan Faris recaptured Tlemcen. He also reconquered the central Maghreb. He took Béjaïa in 1353 and Tunis in 1357, becoming master of Ifriqiya. In 1358 he was forced to return to Fez due to Arab opposition, where he fell sick and was killed.[32]

The Zayyanid king Abu Hammu Musa II (r. 1359–1389) next took the throne of Tlemcen. He pursued an expansionist policy, pushing towards Fez in the west and into the Chelif valley and Béjaïa in the east.[19] He had a long reign punctuated by fighting against the Marinids or various rebel groups.[9] The Marinids reoccupied Tlemcen in 1360 and in 1370.[6] In both cases, the Marinids found they were unable to hold the region against local resistance.[33] Abu Hammu attacked the Hafsids in Béjaïa again in 1366, but this resulted in Hafsid intervention in the kingdom's affairs. The Hafsid sultan released Abu Hammu's cousin, Abu Zayyan, and helped him in laying claim to the Zayyanid throne. This provoked an internecine war between the two Zayyanids until 1378, when Abu Hammu finally captured Abu Zayyan in Algiers.[34]: 141

The historian Ibn Khaldun lived in Tlemcen for a period during the generally prosperous reign of Abu Hammu Musa II, and helped him in negotiations with the nomadic Arabs. He said of this period, "Here [in Tlemcen] science and arts developed with success; here were born scholars and outstanding men, whose glory penetrated into other countries." Abu Hammu was deposed by his son, Abu Tashfin II (1389–94), and the state went into decline.[35]

Decline (late 14th to 16th centuries)

[edit]

In the late 14th and the 15th centuries, the state was increasingly weak and became intermittently a vassal of Hafsid Tunisia, Marinid Morocco, or the Crown of Aragon.[36] In 1386 Abu Hammu moved his capital to Algiers, which he judged less vulnerable, but a year later his son, Abu Tashufin, overthrew him and took him prisoner. Abu Hammu was sent on a ship towards Alexandria but he escaped along the way when the ship stopped in Tunis. In 1388, he recaptured Tlemcen, forcing his son to flee. Abu Tashufin sought refuge in Fez and enlisted the aid of the Marinids, who sent an army to occupy Tlemcen and reinstall him on the throne. As a result, Abu Tashufin and his successors recognized the suzerainty of the Marinids and paid them an annual tribute.[34]: 141

During the reign of the Marinid sultan Abu Sa'id, the Zayyanids rebelled on several occasions and Abu Sa'id had to reassert his authority.[37]: 33–39 After Abu Sa'id's death in 1420 the Marinids were plunged into political turmoil. The Zayyanid emir, Abu Malek, used this opportunity to throw off Marinid authority and captured Fez in 1423. Abu Malek installed Muhammad, a Marinid prince, as a Zayyanid vassal in Fez.[10]: 287 [37]: 47–49 The Wattasids, a family related to the Marinids, continued to govern from Salé, where they proclaimed Abd al-Haqq II, an infant, as the successor to the Marinid throne, with Abu Zakariyya al-Wattasi as regent. The Hafsid sultan, Abd al-Aziz II, reacted to Abu Malek's rising influence by sending military expeditions westward, installing his own Zayyanid client king (Abu Abdallah II) in Tlemcen and pursuing Abu Malek to Fez. Abu Malek's Marinid puppet, Muhammad, was deposed and the Wattasids returned with Abd al-Haqq II to Fez, acknowledging Hafsid suzerainty.[10]: 287 [37]: 47–49 The Zayyanids remained vassals of the Hafsids until the end of the 15th century, when the Spanish expansion along the coast weakened the rule of both dynasties.[34]: 141

By the end of the 15th century the Crown of Aragon had gained effective political control, intervening in the dynastic disputes of the amirs of Tlemcen, whose authority had shrunk to the town and its immediate neighbourship.[35]

Tlemcen was captured in 1551 by the Ottomans of the Regency of Algiers, led by Hassan Pasha. The last Zayyanid sultan, Hasan al-Abdallah, escaped to Oran under Spanish protection.[34]: 156–157 He was baptized and lived under the name of Carlos[38] until his death a few years later. Zayyanid rule thus came to an end.[34]: 156–157

Under the Ottoman Empire Tlemcen quickly lost its former importance, becoming a sleepy provincial town.[39] The failure of the kingdom to become a powerful state can be explained by the lack of geographical or cultural unity, the constant internal disputes and the reliance on irregular Arab nomads for the military.[3]

Economy

[edit]

The city of Tlemcen displaced Tahert (Tiaret) as the main trading hub in the central Maghreb, lying on the west–east route between Fez and Ifriqiya.

Another major route from Oran ran south through Tlemcen to the oases of the Sahara, and onward to the Western Sudan region to the south. The city was directly linked to Sijilmasa, which served as the main northern hub for the trade routes that crossed the desert to the Western Sudanese markets.[28] Oran, a port that the Andalusians had founded in the tenth century to handle the trade with Tahert, came to serve Tlemcen in its trade with Europe. Fez was nearer to Sijilmasa than Tlemcen, but the route to Fez led over the Atlas mountains, while the route to Tlemcen was easier for the caravans.[40] Yaghmurasan made an attempt to capture Sijilmasa in 1257, and succeeded in 1264, holding the town for almost ten years. The Marinids then took Sijilmasa, but most of the trade continued to flow through Tlemcen.[28]

The city of Tlemcen became an important centre, with many schools, mosques and palaces.[14] Tlemcen also housed a European trading centre (funduk) which connected African and European merchants.[41] In particular, Tlemcen was one of the points through which African gold (arriving from south of the Sahara via Sijilmasa or Taghaza) entered the European hands.[41] Consequently, Tlemcen was partially integrated into the European financial system. So, for example, Genoese bills of exchange circulated there, at least among merchants not subject to (or not deterred by) religious prohibitions.[42]

Tlemcen housed several well-known madrasas and numerous wealthy religious foundations, becoming the principal intellectual centre of the central Maghreb. At the souq around the Great Mosque, merchants sold woolen fabrics and rugs from the East, slaves and gold from across the Sahara, local earthenware and leather goods, and a variety of Mediterranean maritime goods "redirected" to Tlemcen by corsairs—in addition to the intentional European imports available at the funduk.[43] Merchant houses based in Tlemcen, such as the al-Maqqari maintained regular branch offices in Mali and the Sudan.[44][45]

Architecture

[edit]

Architecture under the Zayyanids was similar to that found under contemporary dynasties to the west, the Marinids and the Nasrids, continuing western Islamic architectural traditions (also referred to as the "Hispano-Moresque style") and further developing them into the distinctive styles that continued for centuries afterwards.[46][27][47] In 1236 Yaghmurasan added minarets to the Great Mosque of Agadir (an older settlement in the area of Tlemcen), previously founded circa 790, and to the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, previously built under the Almoravids in late 11th and early 12th centuries.[48][49][27]: 42, 179 Both minarets are made of brick and stone and feature sebka relief decoration similar to the earlier Almohad-built Kasbah Mosque of Marrakesh.[27]: 179 Yaghmurasan is also credited with rebuilding or expanding the mosque's courtyard and adding another ornamental ribbed dome to its prayer hall.[49] His successor, Abu Sa'id 'Uthman (r. 1283–1304), founded the Mosque of Sidi Bel Hasan in 1296 in Tlemcen.[27]: 184 The Zayyanids built other religious foundations in and around the city, but many have not survived to the present day or have preserved little of their original appearance.[27]: 187 Madrasas were a new institution which was introduced to the Maghreb in the 13th century and first proliferated under the Zayyanids and their contemporaries.[27]: 168, 187 The Madrasa Tashfiniya, founded by Abu Tashfin I (r. 1318–1337) and later demolished by French colonial authorities in the 19th century, was celebrated for its rich decoration, especially zellij tile decoration with advanced arabesque and geometric motifs whose style was repeated in some subsequent Marinid monuments.[27]: 187 [50]: 526

The Zayyanids installed their government in a citadel or kasbah which was previously founded by the Almoravids in what was then Tagrart (now part of Tlemcen). Yaghmurasan developed this into a fortified palatial complex known as the Meshouar (or Mechouar; Arabic: قلعة المشور, romanized: Qal'at al-Mashwār) to which his successors added.[47]: 137 [51]: 223 Few remains from the Zayyanid period have survived today, but historical sources and archeological excavations have demonstrated the existence of several palaces and residences during that time. Abu Tashfin I built at least three of them, named Dar al-Surur, Dar Abi Fihr, and Dar al-Mulk. Most of the palaces took the form of courtyard buildings, often with a fountain or water basin at their center, gardens, and rich decoration including zellij and carved stucco.[47]: 137–144 [52]: 108 [51]: 223–224 Some regional characteristics are also attested in their design, such as the placement of a central alcove at the back of a large audience chamber, which has precedents in the Zirid palace of 'Ashir and earlier Fatimid palaces further east.[47]: 140 One of the royal palaces was reconstructed in 2010–2011 on top of the former ruins, but fragments of original zellij paving have been documented and preserved.[47]: 140–142 [53] In 1317 Abu Hammu Musa I built the Mechouar Mosque as the official mosque of the palace, though only the minaret and the overall floor plan from the original mosque remain today.[51]: 223 [47]: 108–111 Another palace, stood next to the Great Mosque of Tlemcen and was known as the Qasr al-Qadim ("Old Palace"), most likely the former residence of Almoravid governors in Tagrart. Yaghmurasan used it as royal residence before his move to the Meshouar in the mid-13th-century, but it appears to have been remained in use under subsequent Zayyanid rulers. It too was partly demolished and replaced by other structures during the 19th century and afterwards.[47]: 145–146

Attached to the Qasr al-Qadim was the first royal necropolis (or rawda) of the Zayyanids, which remained the burial site of Zayyanid rulers up until the mid-14th century at least.[47]: 145 After this, the royal necropolis was moved by Abu Hammu II to a new religious complex which he erected in 1361–1362 next to the qubba (mausoleum) of a Muslim saint known as Sidi Brahim. Along with the necropolis, the complex included a mosque and a madrasa, but nearly all of it was in ruins by the 19th century and has since been rebuilt. It remained the site of an important cemetery throughout the later Ottoman period. Excavations have revealed the existence of more rich zellij decoration, of the same style as that of the Tashfiniya Madrasa, which covered some of the tombs.[47]: 111–113

List of Zayyanid rulers

[edit]Chronology of events

[edit]- 1236-1248: Independence war with the Almohad Caliphate

- 1264: Zayyanids conquer Sijilmasa from the Marinids[24]

- 1272: Oujda and Sijilmasa lost to the Marinids[54]

- 1299–1307: Tlemcen besieged by the Marinids[55]

- 1313: Algiers annexed to the Kingdom of Tlemcen[55]

- 1325: Beginning of Zayyanid campaigns toward Hafsid Bejaia and Hafsid Ifriqiya

- 1327: Battle of Tamzezdekt

- 1329: Victory in Battle of er-Rias and Tunis occupied by Zayyanids

- 1337–1348: 1st period of Marinid occupation[56]

- 1352–1359: 2nd period of Marinid occupation[56]

- 1366: Zayyanid-Nasrid victory against Castille[57]

- 1389–1424: Zayyanids recognize Marinid suzerainty[55]

- 1390: Barbary Crusade

- 1423: Capture of Fez by Zayyanid emir Abu Malik and Marinid prince Muhammad installed as Zayyanid vassal in Fez until 1424[10]: 287 [37]: 47–49

- 1424–1500: Zayyanids recognize Hafsid suzerainty[55]

- 1501: Victory over the Portuguese at Mers-el Kébir[58]

- 1505: Mers el Kebir lost to Spain[55]

- 1507: Victory against Spain by the Zayyanids

- 1509: Oran lost to Spain

- 1510: Siege of Algiers, Spanish occupy area and build fortress of Peñón[59]: 365 [60]

- 1512: Zayyanid emir of Tlemcen swears allegiance to Spain[61]

- 1517: Tlemcen besieged by army of Ottoman commander, Aruj[55]

- 1518: Independence restored after the Spanish victory over Aruj[55]

- 1535: Failure of Spanish expedition to Tlemcen

- 1543: Count Alcaudete of Spain starts an expedition to Tlemcen, deposes Zayyanid ruler, Abu Zayyan III,[62][63][64] and installs a vassal ruler, Abu Abdallah Muhammad VI,[65][66] but the latter is expelled and executed after a few months[34]: 155

- 1545: Ibn Ghani, chief of Banu Rashid tribe, invades Tlemcen with Spanish allies and installs another puppet ruler, but Ottomans reinstall former Zayyanid ruler after a month, along with an Ottoman garrison[34]: 155

- 1551: Tlemcen occupied by Algiers, establishment again of Zayyanids on the throne with al-Hasan as ruler

- 1554: Kingdom of Tlemcen becomes an Ottoman protectorate

- 1556: Western Algeria becomes a beylik of the Regency of Algiers by Salah Rais

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This flag is shown in European portolan charts from the mid-14th century century and prior to 1488.[1]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ de Vries, Hubert (2015) [2011]. "AL DJAZAIR - Algeria". Heraldica civica et militara. Archived from the original on 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- ^ Baydal Sala, Vicent (19 Nov 2017). "Religious motivations or feudal expansionism? The Crusade of James II of Aragon against Nasrid Almeria in 1309-10". Complutense University of Madrid. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Abd al-Wadid Dynasty | Berber dynasty". Archived from the original on 2016-08-06. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis, eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 475. ISBN 9780195337709. Archived from the original on 2023-01-11. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ a b الدولة الزيانية في عهد يغمراسن: دراسة تاريخية وحضارية 633 هـ - 681 هـ / 1235 م - 1282 مخالد بلع Archived 2023-06-07 at the Wayback Machine ربي Al Manhal

- ^ a b "The Abdelwadids (1236–1554)". Qantara. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- ^ L'Algérie au passé lointain – De Carthage à la Régence d'Alger, p175

- ^ Despois et al. 1986, p. 367.

- ^ a b c d e f Tarabulsi 2006, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Garrot, Henri (1910). Histoire générale de l'Algérie (in French). Impr. P. Crescenzo.

- ^ Ksour et saints du Gourara: dans la tradition orale, l'hagiographie et les chroniques locales Archived 2023-06-07 at the Wayback Machine. Rachid Bellil. C.N.R.P.A.H.

- ^ Histoire es berbères, 4 Archived 2023-06-07 at the Wayback Machine: et des dynasties musulmanes de l'afrique septentrionale. Abd al-Rahman b. Muhammad Ibn Jaldun. Imprimerie du Gouvernement.

- ^ Khaldoun, Ibn (1856-01-01). Histoire es berbères, 3: et des dynasties musulmanes de l'afrique septentrionale (in French). Translated by William McGuckin de Slane. Imprimerie du Gouvernement. Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ^ a b Bel. 1993, p. 65.

- ^ Piquet, Victor (1937). Histoire des monuments musulmans du Maghreb (in French). Impr. R. Bauche. Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ^ Haddadou, Mohand Akli (2003). Les berbères célèbres (in French). Berti éditions. p. 55. ISBN 978-9961-69-047-5.

- ^ John Murray 1874, p. 209.

- ^ John Murray 1874, p. 210.

- ^ a b c d e Niane 1984, p. 93.

- ^ a b c Tarabulsi 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Ruano 2006, p. 309.

- ^ Hrbek 1997, pp. 34–43.

- ^ "'Abd al-Wadid". Encyclopædia Britannica Vol. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ^ a b Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century - Page 94. UNESCO. 31 December 1984. ISBN 978-92-3-101710-0. Archived from the original on 2023-06-07. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ Lugan, Bernard; Fournel, André (2009). Histoire de l'Afrique: des origines à nos jours - Page 211. Ellipses. ISBN 978-2-7298-4268-0. Archived from the original on 2023-04-09. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ a b Messier, Ronald A. (2009). "ʿAbd al- Wādids". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b c d e f Niane 1984, p. 94.

- ^ Les états de l'Occident musulman aux XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles: institutions gouvernementales et administratives Archived 2023-06-07 at the Wayback Machine Atallah Dhina Office des Publications Universitaires,

- ^ Histoire générale de la Tunisie, Volume 2 Archived 2023-06-07 at the Wayback Machine Hédi Slim, Ammar Mahjoubi, Khaled Belkhodja, Hichem Djaït, Abdelmajid Ennabli Sud éditions,

- ^ a b Fage & Oliver 1975, p. 357.

- ^ a b c d Fage & Oliver 1975, p. 358.

- ^ Hrbek 1997, pp. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674. Archived from the original on 2023-07-20. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- ^ a b Niane 1984, p. 95.

- ^ Hrbek 1997, pp. 41.

- ^ a b c d Société archéologique, historique et géographique du département de Constantine Auteur du texte (1919). "Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société archéologique de la province de Constantine". Gallica. Archived from the original on 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1996). "The 'Abd al-Wadids or Zayyanids or Ziyanids". The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780748696482.

- ^ Wingfield 1868, p. 261.

- ^ Fage & Oliver 1975, p. 356.

- ^ a b Talbi 1997, p. 29.

- ^ Braudel 1979, p. 66.

- ^ Idris 1997, pp. 44–49.

- ^ Niane 1997, p. 245-253.

- ^ Kasaichi 2004, p. 121-137.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 155, 158. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Charpentier, Agnès (2018). Tlemcen médiévale: urbanisme, architecture et arts (in French). Éditions de Boccard. ISBN 9782701805252.

- ^ Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques. pp. 192–197.

- ^ a b Almagro, Antonio (2015). "The Great Mosque of Tlemcen and the Dome of its Maqsura". Al-Qantara. 36 (1): 199–257. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2015.007. hdl:10261/122812.

- ^ Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (2014). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. ISBN 9782350314907.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190624552.

- ^ Bourouiba, Rachid (1973). L'art religieux musulman en Algérie (in French). Algiers: S.N.E.D.

- ^ Charpentier, Agnès; Terrasse, Michel; Bachir, Redouane; Ben Amara, Ayed (2019). "Palais du Meshouar (Tlemcen, Algérie) : couleurs des zellijs et tracés de décors du xive siècle". ArcheoSciences (in French). 43 (2): 265–274. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.6947. ISSN 1960-1360. S2CID 242181689. Archived from the original on 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ^ Caverly 2008, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f g Political Chronologies of the World, pp. 1–18.

- ^ a b Marçais 1986, p. 93.

- ^ J. M., Barral (1974). Orientalia Hispanica: Arabica-Islamica (in French). Brill Archive. p. 37.

- ^ Cheikh Mohammed Abd'al-Djalil al-Tenessy; M. l'abbé J.-J.-L. Bargès (1887). Complément de l'histoire des Beni-Zeiyan, rois de Tlemcen (406) (in French). Paris: E. Leroux. p. 612. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip C. (2006). Historical Dictionary of Algeria. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6480-1. Archived from the original on 2023-01-29. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ Barton, Simon (2009). A History of Spain. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-137-01347-7.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 847. ISBN 978-1-59884-336-1. Archived from the original on 2022-07-09. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ Bargès 1887, p. 451.

- ^ Ruff 1998, p. 91.

- ^ de Vera 1884, p. 160.

- ^ Ruff 1998, p. 95–96.

- ^ de Vera 1884, p. 161.

Sources

[edit]- Bel., A. (1993). "'Abdalwadides". First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. BRILL. p. 65. ISBN 978-90-04-09796-4. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- Braudel, Fernand (1979). Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century: Vol. III: The Perspective of the World. Translated by Sian Reynolds. Univ. Calif. Press & HarperCollins.

- Caverly, R. William (2008). "Hosting Dynasties and Faiths: Chronicling the Religious History Of a Medieval Moroccan Oasis City" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-14.

- Despois, J.; Marçais, G.; Colombe, M.; Emerit, M.; Despois, J.; Marçais, P.H. (1986) [1960]. "Algeria". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. ISBN 9004081143. Archived from the original on 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- Fage, John Donnelly; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- Hrbek, I. (1997). "The disintegration of political unity in the Maghrib". In Joseph Ki-Zerbo & Djibril T Niane (ed.). General History of Africa, vol. IV: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. UNESCO, James Curry Ltd., and Univ. Calif. Press.

- Idris, R. (1997). "Society in the Maghrib after the disappearance of the Almohads". In Joseph Ki-Zerbo & Djibril T Niane (ed.). General History of Africa, vol. IV: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. UNESCO, James Curry Ltd., and Univ. Calif. Press.

- John Murray (1874). A handbook for travellers in Algeria. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- Kasaichi, Masatochi (2004). "Three renowned 'ulama' families of Tlemcen: The Maqqari, the Marzuqi and the 'Uqbani". J. Sophia Asian Studies (22).

- Marçais, G. (1986) [1960]. "ʿAbd al- Wādids". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. ISBN 9004081143. Archived from the original on 2020-12-06. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1984). Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century: 4. University of California Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-435-94810-8. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1997). "Relationships and exchanges among the different regions". In Joseph Ki-Zerbo & Djibril T Niane (ed.). General History of Africa, vol. IV: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. UNESCO, James Curry Ltd., and Univ. Calif. Press.

- Political Chronologies of the World, vol.4 : A Political Chronology of Africa. Taylor & Francis. 2001. ISBN 9781857431162.

- Ruano, Delfina S. (2006). "Hafsids". In Josef W Meri (ed.). Medieval Islamic Civilization: an Encyclopedia. Routledge.

- Talbi, M. (1997). "The Spread of Civilization in the Maghrib and its Impact on Western Civilization". In Joseph Ki-Zerbo & Djibril T Niane (ed.). General History of Africa, vol. IV: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. UNESCO, James Curry Ltd., and Univ. Calif. Press.

- Tarabulsi, Hasna (2006). "The Zayyanids of Tlemcen and the Hatsids of Tunis". IBN JALDUN: STUDIES. Fundación El legado andalusì. ISBN 978-84-96556-34-8. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- Wingfield, Lewis (1868). Under the Palms in Algeria and Tunis ... Hurst and Blackett. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- Bargès, Jean Joseph Léandre (1887). Complément de l'histoire des Beni-Zeiyan, rois de Tlemcen, ouvrage du cheikh Mohammed Abd'al-Djalil al-Tenessy (in French). Paris: E. Leroux.

- Ruff, Paul (15 October 1998). "La campagne de Tlemcen (1543)". La domination espagnole à Oran sous le gouvernement du comte d'Alcaudete, 1534-1558 (in French). Editions Bouchène. pp. 74–101. ISBN 978-2-35676-083-8.

- de Vera, León Galindo (1884). Historia vicisitudes y política tradicional de España respecto de sus posesiones en las costas de África desde la monarquía gótica y en los tiempos posteriores á la restauración hasta el último siglo (in Spanish).

External links

[edit] Media related to Zayyanid dynasty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zayyanid dynasty at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch