Siege of Sanjō Palace

| Siege of the Sanjō Palace | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Heiji Rebellion | |||||||

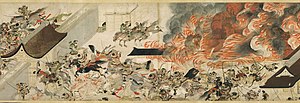

Night Attack on the Sanjō Palace (handscroll detail) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Minamoto Clan, with Fujiwara no Nobuyori | Palace guards protecting Go-Shirakawa | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Minamoto no Yoshitomo | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 500? | Unknown | ||||||

The siege of the Sanjō Palace was the inciting incident of the Heiji Rebellion (平治の乱, Heiji no ran, January 19 – February 5, 1160) during the late Heian period of Japan .[1] The conflict arose from feud between court advisors Fujiwara no Nobuyori and Fujiwara no Michinori, both of the powerful Fujiwara clan, with each respectively allied alongside the warrior clans of the Minamoto (Genji) and Taira (Heiki).[2] The Siege is the focal point of the Japanese war epic (軍記物語, Gunki monogatari) The Tale of Heiji (平治物語, Heiji monogatari) and the corresponding Illustrated Scrolls of the Tales of the Heiji (平治物語絵巻, Heiji monogatari emaki).[3] The Night Attack on Sanjō Palace (Sanjō-den yo-uchi no maki) handscroll is the most prominent of the three extant Illustrated Scrolls and belongs to The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in Boston, Massachusetts, where it currently resides on display.[4][2]

History

[edit]Seeking greater government position, Fujiwara no Nobuyori's request was denied by the then de facto leader of Japan, cloistered ex-Emperor Go-Shirakawa, acting on the counsel of his trusted advisor, Fujiwara no Michinori (also known as Shinzei).[3] In response, Nobuyori joined with Minamoto Yoshitomo, head of the Minamoto warrior clan, and prepared their coup d'état.

In late December 1159, the first year of the Heiji Era, Taira no Kiyomori, head of the Taira clan who militarily supported the throne and Shinzei, left Kyoto on a religious pilgrimage.[2] Exploiting the opportunity, Fujiwara no Nobuyori and Minamoto no Yoshitomo brought a force of roughly five hundred men, attacked in the night, kidnapped cloistered ex-Emperor Go-Shirakawa, and set fire to Sanjō palace. They imprisoned Go-Shirakawa with the current emperor, Emperor Nijō, Go-Shirakawa's son and puppet ruler.[3]

They next attacked the manor house of Shinzei, setting it too aflame and killing all those inside, with the exception of Shinzei himself, who escaped only to be soon found hiding south of Kyoto in hole and decapitated.[2] Nobuyori forced Emperor Nijō to name him both State Minister and General of the Imperial Guard, completing one of the first important steps toward growing his political power.[5]

The illustrated handscroll depicts the burning of the palace, and an inscription discussed the subsequent burning of Shinzei's manor:

On the same day, at the hour of the tiger [four o’clock in the morning], the insurgents attacked and set fire to the residence of Shinzei, located on the streets Anegakōji and Nishi-no-tōin. For the past three or four years, because the use of weapons has been prohibited, peace has now reigned throughout the country; but now, owing to the sudden outbreak of these riots, the Imperial Palace, as well as the capital city, is filled with frightened men. People therefore, both high and low, are grieved and uncertain of what will befall them next.[3]

Subsequently Kiyomori would return, effecting the escape of the Emperor and retired Emperor, and defeat the Minamoto decisively at the Battle of Rokuhara.

Handscroll

[edit]The Night Attack on Sanjō Palace Handscroll is the most prominent of the three extant works remaining of the Illustrated Scrolls of the Tales of the Heiji Era. The massive scroll is based on the text of The Tale of Heiji and depicts Minamoto Yoshitomo's conquest and burning of the Imperial palace.[6] At over 22 feet long and 16 inches tall, the handscroll epitomizes the Yamato-é (literally, Japanese Pictures) style of art.[3]

History, interpretation, and reception

[edit]Despite no known author, the scroll is dated to the mid-thirteenth century, during the Kamakura period.[2][3] The scroll has previously been attributed to a classical Japanese artist named Keion (or Kenin), a member of the Kasuga family of painters, who possibly lived and worked during the mid-late thirteenth century. However, the unsubstantiated facts surrounding both his work and his connection to the handscrolls make definitive claims near impossible.[3]

Art historian Ikeda Shinobu of Chiba University theorizes that given the grandiosity of the scroll, its sexualized depiction of female bodies amidst violence, and the ordered uniformity of the belligerents, the original commissioner or intended recipient was a male aristocrat. Given the rising power of the Samurai in the wake of the Heiji Rebellion and its subsequent decades leading into the Kamakura Period, Shinobu asserts, the martial order of the warriors in the painting in conjunction with the lack of aristocratic depictions mount a compelling argument for the recipient being an upper-class court scholar.[4]

Coupled with evidence of aristocrats of the era entertaining E-awasé ("picture contests") for amusement, the stylistic composition and the magnificence of the Night Attack can be traced to a unique atmosphere among high-class commissioners pushing artists toward more inventive, ambitious Yamato-é compositions.[3] This has led some art historians, such as Kojiro Tomita former head of the Asiatic Arts collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, to laud the handscroll, saying "whether the roll was by Keion or an artist now forgotten, its greatness will remain forever unquestioned."[3][6]

More recently, the infusion of intersectional lenses onto art history, such as Shinobu's gendered deconstruction, have placed the work in a more nuanced light. According to Shinobu, the "sexualized imprint" of the female bodies portrayed in the scroll, emphasized by the outsized number of female to male victims (20 female victims to 3 male), many of which are corpses with exposed breasts, forces reconsideration of the scroll as depicting a "form of pornography to male viewers."[4] This assertion also reinforces the notion of the barbaric invaders as an inferior "other" to be seen as uncivilized brutes contrasting aristocratic sophistication.[4]

Acquisition controversy, ownership

[edit]Amidst the Japanese Imperial Household Museum's nationalist acquisition of historical treasures at the turn to the 20th century, a number of backroom deals were undertaken to finalize a linear canon of Japanese art. This point, considered to be the genesis of Japanese art history, saw art historians Ernest Francisco Fenollosa and Okakura Ten Shin bring this nascent field to the United States. Taking root in Boston at Harvard University and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Fenollosa reportedly may have paid hush money to the dealer who sold him the Night Attack on Sanjō Palace. The dealer wanted 500 yen- an excellent bargain for the time- but Fenollosa paid an extra 500 yen. Art historian Segi Shin’ichi believes Fenollosa paid extra to avoid censure by Japanese authorities. Since then the scroll has and remains property of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[7]

One of other two extant scrolls is owned by the Tokyo National Museum and was designated a National Treasure in 1955.[7] The third remained in private collections until its final owners, the Iwasaki family (founders and multigenerations leaders the multinational Mitsubishi company) founded the Seikado Bunko Museum where it now resides.[2][8]

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. Cassell & Co. p. 200. ISBN 1854095234.

- ^ a b c d e f Murase, Miyeko (1967). "Japanese Screen Paintings of the Hogen and Heiji Insurrections". Artibus Asiae. 29 (2/3): 193–228. doi:10.2307/3250273. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3250273.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tomita, Kojiro (1925). "The Burning of the Sanjō Palace (Heiji Monogatari): A Japanese Scroll Painting of the Thirteenth Century". Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin. 23 (139): 49–55. ISSN 0899-0344. JSTOR 4169962.

- ^ a b c d Shinobu, Ikeda (December 31, 2017), "3. The Image of Women in Battle Scenes: "Sexually" Imprinted Bodies", Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 35–48, doi:10.1515/9780824841577-005, ISBN 978-0-8248-4157-7, retrieved April 1, 2021

- ^ Sansom, George (1958). A History of Japan to 1334. Stanford University Press. pp. 256–258. ISBN 0804705232.

- ^ a b RABB, THEODORE K. (2011). The Artist and the Warrior: Military History through the Eyes of the Masters. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12637-2. JSTOR j.ctt5vm0p7.

- ^ a b Yiengpruksawan, Mimi Hall (March 2001). "Japanese Art History 2001: The State and Stakes of Research". The Art Bulletin. 83 (1): 105–122. doi:10.2307/3177192. JSTOR 3177192.

- ^ "About The Museum | SEIKADO". www.seikado.or.jp. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch