Squaw

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

| |

The English word squaw is an ethnic and sexual slur,[1][2][3][4] historically used for Indigenous North American women.[1][5] Contemporary use of the term, especially by non-Natives, is considered derogatory, misogynist, and racist.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

While squaw (or a close variant) is found in several Eastern and Central Algonquian languages, primarily spoken in the northeastern United States and in eastern and central Canada,[8][9] these languages only make up a small minority of the Indigenous languages of North America. The word "squaw" is not used among Native American, First Nations, Inuit, or Métis peoples.[2][3][4][5] Even in Algonquian, the words used are not the English-language word.[8]

Status

The term squaw is considered offensive by Indigenous peoples in America and Canada due to its use for hundreds of years in a derogatory context[3] that demeans Native American women. This has ranged from condescending images (e.g., picture postcards depicting "Indian squaw and papoose") to racialized epithets.[10][11] Alma Garcia has written, "It treats non-white women as if they were second-class citizens or exotic objects."[10]

Newer editions of dictionaries such as American Heritage, Merriam-Webster online dictionaries, and the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary now list squaw as "offensive", "often offensive", and "usually disparaging".[12][13][14]

While some have studied the elements of Algonquian words that might be related to the word, the consensus among Native women, and Native people in general, is that—no matter the linguistic origins—the word is too offensive,[1][2][3][5][6] and that any "reclamation" efforts would only apply to the small percentage of Native women from the Algonquian-language groups, and not to the vast majority of Native women who feel degraded by the term.[4][9] Indigenous women who have addressed the history and depth of this word state that this degrading usage is now too long, and too painful, for it to ever take on a positive meaning among Indigenous women or Indigenous communities as a whole.[2][5][4]

Feminist and anti-racist groups have also worked to educate and encourage the disuse of the term in normal discourse. When asked why "it never used to bother Indian women to be called squaw," and "why now?" an American Indian Movement group responded in 2006:

Were American Indian women or people ever asked? Have you ever asked an American Indian woman, man, or child how they feel about [the "s" word]? (... it has always been used to insult American Indian women.) Through communication and education American Indian people have come to understand the derogatory meaning of the word. American Indian women claim the right to define ourselves as women and we reject the offensive term squaw.

— from the web page of the American Indian Movement, Southern California Chapter[4]

In 2015, Jodi Lynn Maracle (Mohawk) and Agnes Williams (Seneca) petitioned the Buffalo Common Council to change the name of Squaw Island to Deyowenoguhdoh.[5] Seneca Nation President Maurice John Sr., and Chief G. Ava Hill of the Six Nations of the Grand River wrote letters petitioning for the name change as well, with Chief Hill writing,

The continued use and acceptance of the word 'Squaw' only perpetuates the idea that indigenous women and culture can be deemed as impure, sexually perverse, barbaric and dirty ... Please do eliminate the slur 'Squaw' from your community.[5]

The Buffalo Common Council then voted unanimously to change the name to Unity Island.[15]

In November 2021, the United States Department of the Interior, ("DOI") headed by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, declared squaw to be a derogatory and racist term and began formally removing the term from use on the federal level.[1] On September 8, 2022 the DOI officially replaced all place names containing the word and published a list of the new names.[16][17]

History

Eastern and Central Algonquian morphemes (smallest units of meaning) meaning "woman" (mostly found as components in longer words) include: Massachusett squàw ("woman"), Abenaki -skwa ("female, wife"), Mohegan-Pequot sqá, Cree iskwew / ᐃᐢᑫᐧᐤ (iskeyw, "woman"), Ojibwe ikwe ("woman"). Variants in other related languages are: esqua, sqeh, skwe, que, kwa, exkwew, xkwe. These are all derived from Proto-Algonquian *eθkwe·wa ("(young) woman").[8][18][9] According to linguist Ives Goddard, the notion that the word originally referred to a woman's vagina is inaccurate.[19]

In the first published report of Indigenous American languages in English, A Key into the Language of America, written in 1643, Puritan Minister Roger Williams wrote his impressions of the Narragansett language. Williams noted morphemes that he considered to be related to "squaw" and provided the definitions he felt fit them, as a learner, including: squaw ("woman"), squawsuck ("women"), keegsquaw ("virgin or maid"), segousquaw ("widower"), and squausnit ("woman's god").[20]

In most colonial texts squaw was used as a general word for Indigenous women.

The Massachusett Bible was printed in the Massachusett language in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1663. It used the word squa in Mark 10:6 as a translation for "female". It used the plural form squaog in 1 Timothy 5:2 and 5:14 for "younger women".[19]

A will written in the Massachusett language by a native preacher from Martha's Vineyard uses the word squa to refer to his unmarried daughters. In the Massachusett language, squa was an ancient and thoroughly decent word.[19]

One of the earliest appearances of the term in English in print is "the squa sachim, or Massachusetts queen" in the colonial booklet Mourt's Relation (1622), one of the first chronicles of the Plymouth Colony written by European colonists, including the story of the Pilgrims' first Thanksgiving.[19] The sachem or sachim is the elected chief of a Massachusett tribe, and the booklet used Pidgin Massachusett to call the chief's wife the "squa sachim".[19]

Records accompanying sketches by Alfred Jacob Miller document mid-19th century usage of the term in the United States. Miller wrote notes in 1858-1860 for each picture, many of which included Indigenous women. These were published in the 1951 catalog of a Miller exhibition. For Indian Girl reposing, Miller wrote, "Before they are 16 years of age, these girls may be said to have their heyday, and even then if they become the wives or mates of Trappers, are comparatively happy, for they generally indulge them to their hearts' content; should they become however the squaws of Indians, their lives are subjected to the caprices of a tyrant too often, whose ill treatment is the rule and kindness their exception. Nothing so strikingly distinguishes civilized from savage life as the treatment of women. It is in every particular in favor of the former." For "Bourgeois" Walker, & his Squaw, Miller describes his depiction of the fur trader made in 1858 thusly:

"The sketch exhibits a certain etiquette. The Squaw's station in travelling is at a considerable distance in the rear of her liege lord, and never at the side of him. [Walker] had the kindness to present the writer a dozen pair of moccasins worked by this squaw - richly embroidered on the instep with colored porcupine quills."[21][22][23]

Edgar Allan Poe uses the word in his 1838 novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket.[24]

The 1887 Canadian novel An Algonquin Maiden uses the term squaw four times; twice as "squaw-snake" to refer to a female snake, and twice to refer to a woman from an Algonquin tribe.[25]

Colville / Okanagan author Mourning Dove, in her 1927 novel, Cogewea, the Half-Blood had one of her characters say,

If I was to marry a white man and he would dare call me a 'squaw'—as an epithet with the sarcasm that we know so well—I believe that I would feel like killing him.[26]

E. B. White's 1961 story "The Years of Wonder", derived from his 1923 journal of a shipboard trip to Alaska, included, "Mr. Hubbard ... saw that Siberia was represented by a couple of dozen furry Eskimos and one squaw man; they came aboard from a skin boat as soon as the Buford dropped her hook."[27]

Science fiction author Isaac Asimov, in his novel Pebble in the Sky (1950), wrote that science-fictional natives of other planets would use slurs against natives of Earth, such as, "Earthie-squaw".[28]

LaDonna Harris, a Comanche social activist who spoke about empowering Native American schoolchildren in the 1960s at Ponca City, Oklahoma, recounted:

We tried to find out what the children found painful about school [causing a very high dropout rate]. (...) The children said that they felt humiliated almost every day by teachers calling them "squaws" and using all those other old horrible terms.[29]

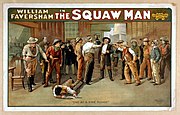

As a word referring to a woman, it was sometimes used to denigrate men, as in "squaw man," meaning either "a man who does woman's work" or "a white man married to an Indian woman and living with her people".[30]

Sexual references

An early comment in which squaw appears to have a sexual meaning is from the Canadian writer E. Pauline Johnson, who was of Mohawk heritage, but spent little time in that culture as an adult.[31] She wrote about the title character in An Algonquin Maiden by G. Mercer Adam and A. Ethelwyn Wetherald:

Poor little Wanda! not only is she non-descript and ill-starred, but as usual the authors take away her love, her life, and last and most terrible of all, reputation; for they permit a crowd of men-friends of the hero to call her a "squaw" and neither hero nor authors deny that she is a squaw. It is almost too sad when so much prejudice exists against the Indians, that any one should write up an Indian heroine with such glaring accusations against her virtue, and no contradictory statements from either writer, hero or circumstance.[32]

Statements that squaw came from a word meaning "female genitals" gained currency in the 1970s, but have since been found to be inaccurate.[19]

Efforts to rename placenames and terms

In November 2021, the U.S. Department of the Interior declared squaw to be a derogatory term and began formally removing the term from use on the federal level, with Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) announcing the creation of a committee and process to review and replace derogatory names of geographic features.[1] In a press release, Secretary Haaland announced,

Racist terms have no place in our vernacular or on our federal lands. Our nation’s lands and waters should be places to celebrate the outdoors and our shared cultural heritage – not to perpetuate the legacies of oppression. Today’s actions will accelerate an important process to reconcile derogatory place names and mark a significant step in honoring the ancestors who have stewarded our lands since time immemorial.[1]

This follows decades of work by Indigenous activists, both locally and in more general educational efforts, to rename the locations across North America that have contained the word, as well as to eliminate the word from the lexicon in general.[4][33][34] The work follows previous actions by the Board on Geographic Names which recognized place names containing words that were widely recognized as being pejorative or derogatory for Black and Japanese people.[35]

- In 1988 the E.B. Campbell Dam on the Saskatchewan River was officially renamed; formerly it had been the Squaw Rapids Dam.

- Ioway Creek (formerly Squaw Creek), a 41-mile (66 km) long tributary of the S. Skunk River in central Iowa, known for its flooding and flash flooding of several highly developed portions of the eastern and southeastern portions of the Iowa State University campus in the city of Ames, was officially renamed by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names on February 11, 2021.[36]

- The Montana Legislature created an advisory group in 1999 to replace the word squaw in local place names and required any replacement of a sign to bear the new name.[37]

- The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission and the Maine Legislature collaborated in 2000 to pass a law eliminating the words squaw and squa from all of the state's waterways, islands, and mountains. Some of those sites have been renamed with the word moose; others, in a nod to Wabanaki language-recovery efforts, are now being given new place-appropriate names in the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy languages.[38] Twenty years after the law's passage, the owner of Big Squaw Mountain Resort near Greenville, Maine refused to consider changing the resort's name, even though its namesake was changed to Big Moose Mountain following the passage of the statewide law.[39]

- The American Ornithologists' Union changed the official American English name of the long-tailed duck, (Clangula hyemalis) from oldsquaw to the long-standing British name, because of wildlife biologists' concerns about cooperation with Native Americans involved in conservation efforts, as well as for standardization.[40]

- Piestewa Peak in Phoenix, Arizona, replaced the name Squaw Peak in 2003; the new name honors Iraq War casualty PFC Lori Piestewa (Hopi), the first Native American woman to die in combat for the U.S.

- Members of Coeur d'Alene Tribe in Idaho called for the removal of the word squaw from the names of 13 locations in that state in October 2006. Many tribal members reportedly believe the "woman's genitals" etymology.[41]

- The British Columbian portion of a tributary of the Tatshenshini River was officially renamed Dollis Creek by the BC Geographical Names Office on January 15, 2008.[42] The name Squaw Creek had been previously rescinded on December 8, 2000.

- Frog Woman Rock was the name chosen to honor the cultural heritage of the Pomo peoples of the region between Hopland and Cloverdale in the Russian River canyon. The State Office of Historic Preservation updated the name of the California Historical Landmark, formerly called Squaw Rock, in 2011.

- In 2015, Unity Island (Deyowenoguhdoh in the Seneca language) was officially adopted as the name for the island formerly called Squaw Island. The Buffalo Common Council voted in the name change came after being petitioned by members of the Seneca Nation of New York.[5]

- An application was made to the Nova Scotia Geographic Information Service in late 2016 to rename Squaw Island, Cape Negro, Cape Negro Island and Negro Harbour in Shelburne County.[43]

- In 2017, The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service renamed the Squaw Creek National Wildlife Refuge in Missouri to Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge in 2017.

- Squaw Ridge in Sierra Nevada was formally renamed Hungalelti Ridge in September 2018, after a proposal by the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California.[44]

- Saskatchewan's Killsquaw Lake—the site of a 19th-century massacre of a group of Cree women—was renamed Kikiskitotawânawak Iskêwak on November 20, 2018. The new name means "we honour the women" in Cree. The renaming effort was led by Indigenous lawyer Kellie Wuttunee in consultation with Cree elders and community leaders. "To properly respect and honour First Nations women, we can no longer have degrading geographic names in Saskatchewan. ... Even if unintentional, the previous name was harmful. By changing the name, we are giving a voice to the ones who are silenced," said Wuttunee, who has worked on missing and murdered Indigenous women cases. "Names are powerful. They inform our identity."[45]

- After similar rumours over the years, on August 20, 2020, it was reported that Squaw's Tit near Canmore, Alberta would be renamed to avoid racist and misogynistic naming. Talks with the Stoney Nakoda community to find a culturally appropriate name and a request to support the initiative were brought to the Municipal District of Bighorn in September 2020.[46] on September 29, 2020, the peak was officially renamed to Anûkathâ Îpa, meaning 'Bald Eagle Peak' in the Stoney Nakoda language.[47]

- In 2020, Squaw Valley Academy changed its name to Lake Tahoe Preparatory School.

- Palisades Tahoe was the new name of Squaw Valley Ski Resort as of September 13, 2021.[48] The decision was announced after consulting with the local Washoe Tribe and extensive research into the etymology and history of the term squaw.[49]

- Serenity Mountain Retreat was the new name of the Squaw Mountain Ranch nudist resort as of December 2021.[50][better source needed]

- Orange Cove is an agricultural community located along the eastern foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, incorporated in 1948 and has a population of 9,078. On January 27, 2021, the City Council deferred a proposal seeking to change the name of the Squaw Valley area of Fresno County to "Nim Valley", to allow the city to seek more community input.[51]

- Yokuts Valley, California, became the official name of the basin formerly named "Squaw Valley". It had been part of long process of community debate from 2020 into early 2023.[52][53][54][55]

- The United States Department of the Interior announced in 2022 that it would rename 660 mountains, rivers, and other locations "to remove derogatory terms whose expiration dates are long overdue," including the word "squaw."[56] In September 2022, a list of approved names was published by the United States Geological Survey replacing 643 placenames containing "squaw".[57][58]

- On September 23, 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom of California signed a law directing state and local authorities to remove "squaw" from almost 100 geographic features and place names throughout the state.[54][55] California State Parks and the California Department of Transportation announced reviews of markers and place names to be renamed or rescinded.[59]

- In January 2023, Squaw Gap in North Dakota became Homesteaders Gap.[60]

- Squaw Cap in New Brunswick was renamed Evergreen in January 2024, along with the nearby mountain of the same name.[61]

The term persists in the officially sanctioned names of several places in the U.S., as well as certain businesses, such as Squaw Lake (Minnesota), Squaw Grove Township (DeKalb County, Illinois), Squaw Township (Iowa), Squaw Canyon Oil Field, Squaw Creek Southern Railroad, and Squaw Peak Inn.

See also

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Indigenous feminism

- Native American feminism

- Nigger

- Stereotypes of Native Americans

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Secretary Haaland Takes Action to Remove Derogatory Names from Federal Lands" (Press release). U.S. Department of the Interior. November 19, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

Secretarial Order 3404 formally identifies the term "squaw" as derogatory and creates a federal task force to find replacement names for geographic features on federal lands bearing the term. The term has historically been used as an offensive ethnic, racial, and sexist slur, particularly for Indigenous women.

- ^ a b c d e Vowel, Chelsea (2016). "Just Don't Call Us Late for Supper - Names for Indigenous Peoples". Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit Issues in Canada. Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada: Highwater Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1553796800.

Let's just agree the following words are never okay to call Indigenous peoples: savage, red Indian, redskin, primitive, half-breed, squaw/brave/papoose.

- ^ a b c d e National Museum of the American Indian (2007). Do All Indians Live in Tipis?. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-115301-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mathias, Fern (December 2006). "SQUAW - Facts on the Eradication of the "S" Word". Western North Carolina Citizens For An End To Institutional Bigotry. American Indian Movement, Southern California Chapter. Archived from the original on August 2, 2002. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

Through communication and education American Indian people have come to understand the derogatory meaning of the word. American Indian women claim the right to define ourselves as women and we reject the offensive term squaw.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schulman, Susan (January 16, 2015). "Squaw Island to be renamed 'Deyowenoguhdoh'". The Buffalo News. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

The proposed name change comes at the request of Native Americans, who say the word "squaw" is a racist, sexist term

- ^ a b Hirschfelder, Arlene B.; Paulette Fairbanks Molin (2012). The Extraordinary Book of Native American Lists. Scarecrow. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8108-7709-2.

- ^ King, C. Richard, "De/Scribing Squ*w: Indigenous Women and Imperial Idioms in the United States" in the American Indian Culture and Research Journal, v27 n2 p1-16 2003. Accessed October 9, 2015

- ^ a b c Deborah Pelletier, Terminology Guide: Research on Aboriginal Heritage, Library and Archives, Canada, 2012. (PDF archived at internet archive) (Available on docplayer). Accessed September 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Squaw – Facts on the Eradication of the 'S' Word". Western North Carolina Citizens For An End To Institutional Bigotry. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

When people argue that the word originates in American Indian language point out that: Although scholarship traces the word to the Massachusset Indians back in the 1650s, the word has different meanings (or may not exist at all) in hundreds of other American Indian languages. This claim also assumes that a European correctly translated the Massachusset language to English—that he understood the nuances of Indian speech.

- ^ a b Garcia, Alma (2012). Contested images women of color in popular culture. Lanham, Maryland: Altimia Press. pp. 157–168. ISBN 978-0759119635.

- ^ Green 1975

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary "squaw". Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary."Squaw". Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England. Entry: "Squaw".

- ^ McNeil, Harold (July 6, 2015). "Unity Island becomes official name of Niagara River plot". The Buffalo News. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ "Interior Department Completes Removal of "Sq___" from Federal Use". U.S. Department of the Interior. September 8, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

- ^ "Name Replacements". USGS. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

- ^ Cutler 1994; Goddard 1996, 1997. Possibly as early as 1621.

- ^ a b c d e f Goddard, Ives (April 15, 1997). "The True History of the Word Squaw. Slightly revised version of a letter, "Since the word squaw continues to be of interest", printed in Indian Country News" (PDF). p. 17A.

In its historical origin, however, the word squaw is perfectly innocent ... It is as certain as any historical fact can be that the word squaw that the English settlers in Massachusetts used for "Indian woman" in the early 1600s was adopted by them from the word squa that their Massachusett-speaking neighbors used in their own language to mean "female, younger woman," and not from Mohawk ojiskwa' "vagina," which has the wrong shape, the wrong meaning, and was used by people with whom they then had no contact.

- ^ Williams, Roger (1936) [1643]. A Key into the Language of America (reprint). Baxter, Reprinted by Providence. ISBN 1-55709-464-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Alfred Jacob Miller (1951). The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (1837) from the notes and water colors in the Walters Art Gallery, with an account of the artist by Marvin C. Ross. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 71, 78.

- ^ ""Bourgeois" W---r, and His Squaw | 37.1940.78".

- ^ DeVoto, Bernard (1947). Across The Wide Missouri. Illustrated by Alfred Jacob Miller. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan (1838). The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Penguin. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-14-043748-5.

This man was the son of an Indian squaw of the tribe of Upsarokas, who live among the fastnesses of the Black Hills near the source of the Missouri.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Adam, G. Mercer; Wetherald, A. Ethelwyn (1887). An Algonquin Maiden: A Romance of the Early Days of Upper Canada. Montreal: John Lovell and Son.

Let me contrive to win the heart of this vain squaw-snake, and then with her aid I shall be able to destroy her husband ... Oh, there is no doubt that Big Bear knew all about the best way to make love, for very soon the squaw-snake began to show great discontent with her husband ... "Come, Ned, try to be entertaining for once; tell us about the pretty Indian girl you were mooning with." "What did you say?" demanded Edward, freezingly. "You heard perfectly well what I said." "What do you mean by it?" "Oh, I mean the pretty squaw you were spooning with, if that suits you better." ... "Only it was town talk in Barrie last Fall that you had become infatuated with the sweet little squaw to such an extent that your charming sister, with commendable prudence and foresight, had you put out of harm's way as speedily as possible."

- ^ Mourning Dove. 1927 (1981 edition). Cogewea, the Half-Blood, p. 112. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8110-2.

- ^ E. B. White (1977). "The Years of Wonder". Essays of E. B. White. New York: Harper & Row. p. 192. ISBN 0-06-014576-5.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac. 1971. Pebble in the Sky. Fawcett, Greenwich, Conn.

- ^ Harris, LaDonna. 2000. LaDonna Harris, A Comanche Life, edited by H. Henrietta Stockel, p. 59, University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ Hodge, Frederick Webb. 1910. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnology Bulletin 30. Retrieved November 16, 2007. This was a popular literary stereotype, as in The Squaw Man

- ^ Lyon, George W. (1990). "Pauline Johnson: A Reconsideration". Studies in Canadian Literature. 15 (2): 136. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Pauline. 1892. "A Strong Race Opinion on the Indian Girl in Modern Fiction". Reprinted in Keller, Betty. 1987. Pauline: A Biography of Pauline Johnson, p. 119. Formac. ISBN 0-88780-151-X.

- ^ "From Negro Creek to Wop Draw, place names offend". NBC News. February 26, 2012.

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini (December 2006). "Removing 'Squaw' from the Lexicon". The Sacramento Union. Archived from the original on September 21, 2005. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (November 19, 2021). "Interior Secretary Deb Haaland moves to ban the word 'squaw' from federal lands". NPR.

- ^ Gehr, Danielle (February 16, 2021). "'I am just amazed': After years of lobbying, U.S. board agrees to change the name of a central Iowa creek". The Ames Tribune.

- ^ Montana Code 2-15-149

- ^ Carrier, 2000.

- ^ Fleming, Deirdre (August 28, 2020). "Owner rebuffs call to change name of ski area near Greenville". Press Herald.

- ^ American Ornithologists' Union, 2000.

- ^ Hagengruber, 2006.

- ^ "Dollis Creek". BCGNIS. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ Pam, Berman (June 17, 2020). "2 years after complaint, review for Barrington communities with offensive names pending". CBC News.

- ^ "Squaw Ridge in Sierra Nevada renamed after proposal by Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California". Tahoe Daily Tribune. September 18, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "Indigenous lawyer led push to rename Sask.'s Killsquaw Lake to honour Cree women who died in 19th century - New name Kikiskitotawânawak Iskêwak means 'we honour the women'". CBC News. November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ Dulewich, Jenna (August 20, 2020). "Moving Mountains: How Bow Valley is taking a stand against a peak with a racist name". Canmore, AB. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ "Beyond Local: Stoney Nakoda restores traditional name to peak with racist nickname". StAlbertToday.ca. September 29, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "See the tremendous history and legend of Palisades Tahoe, formerly Squaw Valley," Modesto Bee. September 13, 2021. Accessed September 13, 2021.

- ^ "Squaw Valley Name Change". Squaw Alpine. August 19, 2020. Archived from the original on August 26, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Serenity Mountain Retreat archived on December 5, 2021

- ^ "Effort to Rename County's Squaw Valley Area Put on Hold After Complaints". January 27, 2021.

- ^ Seidman, Lila (January 8, 2022). "Indigenous group goes to federal board to rename Squaw Valley". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ Montalvo, Melissa (November 19, 2021). "Should the community of Squaw Valley change its name?". CalMatters. Sacramento, California. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Sahagún, Louis (September 25, 2022). "New law will remove the word 'squaw' from California place names". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "On Native American Day, Governor Newsom Signs Legislation to Support California Native Communities, Advance Equity and Inclusion" (Press release). Sacramento, California: Office of the Governor of California. September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ McGreevy, Nora. "U.S. Will Rename 660 Mountains, Rivers and More to Remove Racist Word". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Nguyen, Thao. "US changes names of nearly 650 places with racist Native American women term". USA Today. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "Official Replacement Names for Sq_". Geographic Names Information System. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "State Agencies Announce Steps to Address Discriminatory Names, Inequities in State Parks and Transportation System Features" (Press release). Sacramento, California: California State Parks. September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ "Interior Department Completes Vote to Remove Derogatory Names from Five Locations". United States Department of the Interior. January 12, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ McNally, Trevor (November 23, 2023). "Racial Slur Dropped from N.B. community's name". The Tribune. p. A1. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

References

- Carrier, Paul. June 27, 2000. "'Squaw' renaming may have exception." Portland Press Herald.'

- Cutler, Charles L. 1994. O Brave New Words! Native American Loanwords in Current English. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2655-8

- Green, Rayna. 1975. "The Pocahontas Perplex: The Image of Indian Women in American Culture." Massachusetts Review 16:698–714.

- Hagengruber, James. 2006. "Tribe wants 'squaw' off map". SpokesmanReview.Com (Idaho), October 6, 2006. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

Further reading

- Laurent, Chief Joseph. 1884. New Familiar Abenakis and English Dialogues. Quebec, Leger Brousseau. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- Masta, Henry Lorne. 1932. Abenaki Indian Legends, Grammar and Place Names. Odanak, P.Q., Canada.

- Mihesuah, Devon Abbott. 2003. Indigenous American Women: Decolonization, Empowerment, Activism. University of Nebraska Press.

External links

- Around Ethnic Slurs: Squaw

- SQUAW – Facts on the Eradication of the "S" Word at Teach Respect Not Racism – Western North Carolina Citizens For An End To Institutional Bigotry

- Squelching the S-Word at Blue Corn Comics, collection of articles and correspondence on topic

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch