Susan La Flesche Picotte

Susan La Flesche Picotte | |

|---|---|

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte | |

| Born | June 17, 1865 Omaha Reservation, United States |

| Died | September 18, 1915 (aged 50) Walthill, Nebraska, United States |

| Nationality | Omaha, Ponca, Iowa, French, and Anglo-American descent |

| Alma mater | Hampton Institute Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Known for | First Indigenous woman to become a physician in the United States |

| Parent(s) | Joseph La Flesche and Mary Gale |

| Relatives | Susette La Flesche (sister) Francis La Flesche (half-brother) |

Susan La Flesche Picotte (June 17, 1865 – September 18, 1915)[1] was a Native American medical doctor and reformer and member of the Omaha tribe. She is widely acknowledged as one of the first Indigenous people, and the first Indigenous woman, to earn a medical degree.[2] She campaigned for public health and for the formal, legal allotment of land to members of the Omaha tribe.

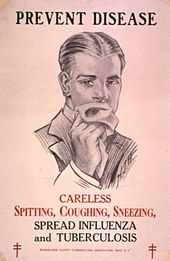

Picotte was an active social reformer as well as a physician. She worked to discourage the consumption of alcohol on the reservation where she worked as the physician, as part of the temperance movement. Picotte also campaigned for the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis, which then had no cure, as part of a public health campaign. She also worked to help other Omaha navigate the bureaucracy of the Office of Indian Affairs and receive the money owed to them for the sale of their land.

Early life

[edit]Susan La Flesche was born in June 1865 on the Omaha Reservation in eastern Nebraska. Her parents were culturally Omaha, had both European and Indigenous ancestry, and had lived for periods of time beyond the borders of the reservation. They married in either 1845 or 1846.[3]

La Flesche's father, Joseph La Flesche (also called Iron Eye), was of Ponca and some French Canadian ancestry. He was educated in St. Louis, Missouri, but returned to the reservation as a young man. He identified culturally as Omaha. In 1853, he was adopted by Chief Big Elk, who chose him as his successor, and La Flesche became the principal leader of the Omaha tribe around 1855.[4] Iron Eye encouraged a certain amount of assimilation, particularly through the policy of land allotment, which caused some friction among the Omaha.[5]

La Flesche's mother, Mary Gale, was the daughter of Dr. John Gale, a white United States Army surgeon stationed at Fort Atkinson, and Nicomi, a woman of Omaha, Otoe, and Iowa heritage.[3][6] Gale was also the stepdaughter of prominent Nebraska fur trader and statesman Peter A. Sarpy.[7] Like her husband, Mary Gale identified as Omaha. Although she understood French and English, she reportedly refused to speak any language other than Omaha.[4]

La Flesche was the youngest of four girls, including her sisters Susette (1854–1903), Rosalie (1861–1900), and Marguerite (1862–1945).[8] Her older half-brother Francis La Flesche, born in 1857 to her father's second wife, later became a renowned ethnologist, anthropologist and musicologist (or ethnomusicologist), who specialized in the study of the Omaha and Osage cultures. As she grew, La Flesche learned the traditions of her heritage, but her parents felt certain rituals would be detrimental in the white world. They did not give La Flesche an Omaha name and prevented her from receiving traditional tattoos across her forehead.[9] She spoke Omaha with her parents (especially her mother), but her father and oldest sister Susette encouraged her to speak English with her sisters, so that she would be fluent in both languages.[10]

As a child, La Flesche witnessed a sick Indian woman die after a white doctor refused to treat her. She later credited this tragedy as her inspiration to train as a physician, so she could provide care for the people with whom she lived on the Omaha Reservation. [11]

Education

[edit]Early education

[edit]As a child, La Flesche was educated at the mission school on the Omaha reservation. It was run first by Presbyterians and then by Quakers, after the enactment of President Ulysses S. Grant's Peace Policy in 1869.[10] The reservation school was a boarding school where Native children were taught the practices of European Americans to assimilate them into white society.[12]

After several years at the mission school, La Flesche left the reservation for Elizabeth, New Jersey, where she studied at the Elizabeth Institute for two and a half years.[13] She returned to the reservation in 1882 and taught at the agency school. She left again to study at the Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, from 1884 to 1886.[14] It had been established as an historically black college after the American Civil War, but also educated Native American students.[15]

La Flesche attended Hampton with her sister Marguerite, her stepbrother Cary, and ten other Omaha children. The girls learned housewifery skills and the boys learned vocational skills as part of the practical skills promoted at the school.[16] While La Flesche was a student at the Hampton Institute, she became romantically involved with a young Sioux man named Thomas Ikinicapi.[17] She referred to him affectionately as "T.I.", but broke off her relationship with him before graduating from Hampton. La Flesche graduated from Hampton on May 20, 1886, as the salutatorian of her class.[18] She was also awarded the Demorest prize, which is given to the graduating senior who receives the highest examination scores during the junior year.[18]

La Flesche decided in 1886 to apply to medical school.[19]

Medical school

[edit]

Though women were often healers in Omaha Indian society, it was uncommon for women in the United States to go to medical school, and in the late 19th century, only a few medical schools accepted women.[19] La Flesche applied to medical school in 1886[19] and was accepted to the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP), in Philadelphia, which had been established in 1850 as one of the few medical schools on the east coast for the education of women.[20]

La Flesche asked for financial assistance from family friend Alice Fletcher, an ethnographer from Massachusetts who had a broad network of contacts within women's reform organizations.[21] La Flesche had previously helped nurse Fletcher back to health following a flareup of inflammatory rheumatism.[18] Fletcher encouraged La Flesche to appeal to the Connecticut Indian Association, a local auxiliary of the Women's National Indian Association (WNIA).[22] The WNIA sought to "civilize" Native women by encouraging Victorian values of domesticity, and sponsored field matrons whose task was to teach Native American women "cleanliness" and "godliness".[23]

La Flesche, in writing to the Connecticut Indian Association, had described her desire to enter the homes of her people as a physician and teach them hygiene as well as curing their ills, a mission in line with the Victorian virtues of domesticity that the Association wanted to encourage.[24] The Association sponsored La Flesche's medical school tuition, and also paid for her housing, books and other supplies. She is considered the first person to receive aid for professional education in the United States.[25][11] The Association requested that she remain single during her time at medical school and for several years after her graduation in order to focus on her practice.[17]

At the WMCP, La Flesche studied chemistry, anatomy, physiology, histology, pharmaceutical science, obstetrics, and general medicine, and, like her peers, did clinical work at facilities in Philadelphia alongside students from other colleges, both male and female.[26] While attending medical school, La Flesche began to dress like her white classmates and wore her hair in a bun as they did.[18]

After La Flesche's second year in medical school, she returned home to help her family, many of whom had fallen ill due to a measles outbreak. During the rest of her schooling, she would write letters back home giving medical advice.[18]

On March 14, 1889, La Flesche graduated from medical as valedictorian of her class after three years of study.[27][28]

In June 1889, La Flesche applied for the position of government physician at the Omaha Agency Indian School; she was offered the position less than two months later.[29] After her graduation, she went on a speaking tour at the request of the Connecticut Indian Association, assuring white audiences that Native Americans could benefit from white civilization.[30] She maintained her ties with the Association after medical school. They appointed her as a medical missionary to the Omaha after graduation, and the Association funded purchase of medical instruments and books for her during her early years of practicing medicine in Nebraska.[24]

Medical practice

[edit]

La Flesche returned to the Omaha reservation in 1889 to work as the physician at the government boarding school on the reservation, run by the Office of Indian Affairs. There, she was responsible for teaching the students about hygiene and keeping them healthy.[31]

Though she was not obligated to care for the broader community, the school was closer to many people than the official reservation agency, and La Flesche cared for many members of the community as well as for the children of the school.[32] La Flesche often had 20-hour workdays and was responsible for the care of over 1,200 people.[33] From her office in a corner of the schoolyard, with the supplies provided by the Connecticut Indian Association, she helped people with their health but also with more mundane tasks, such as writing letters and translating official documents.[34]

La Flesche was widely trusted in the community, making house calls and caring for patients sick with tuberculosis, influenza, cholera, dysentery, and trachoma.[34] Her first office, which measured 12 by 16 feet, doubled as a community meeting place.[35]

For several years, she traveled the reservation caring for patients, on a government salary of $500.00 per year, in addition to the $250 from the Women's National Indian Association for her work as a medical missionary.[34]

In December 1892, La Flesche became very sick, and was bedridden for several weeks. In 1893, she took time off to care for her ailing mother and also to restore her own health.[36] She resigned later that year to take care of her dying mother.[36]

In 1894, La Flesche met and became engaged to Henry Picotte, a Sioux Indian from the Yankton agency. He had been married before and divorced his wife.[37] Many of La Flesche's friends and family were reportedly surprised at the romance, but the two were married in June 1894.[38]

Picotte and her husband had two sons: Caryl, born in 1895 or 1896, and Pierre, born in early 1898.[39] Picotte continued to practice medicine after the birth of her children, depending on the support of her husband to make that possible. Picotte's practice treated both Omaha and white patients in the town of Bancroft and surrounding communities.[31] If necessary, Picotte would even take her children on house calls with her sometimes.[40]

Public health reforms

[edit]Temperance

[edit]In addition to caring for the Omaha people's immediate medical problems, Picotte sought to educate her community about preventive medicine and other public health issues, including temperance. Alcoholism was a serious problem on the Omaha reservation, and a personal one for Picotte: her husband Henry was an alcoholic.[41] White businesspeople used alcohol to take advantage of Omahas while making land deals. Picotte, as reservation physician and a prominent member of the community, was well aware of the damage such practices caused.[42] La Flesche supported measures such as coercion and punishment to dissuade individuals from alcohol consumption within the Omaha community. Under her father's rule, a secret police system was instilled which supported corporal punishment to discipline those who consumed alcohol.[40]

Picotte campaigned against alcohol consumption, giving lectures about the virtues of temperance, and embracing coercive efforts as well, such as prohibition.[43] In the early 1890s, she campaigned for a prohibition law in Thurston County, which did not pass, in part because some liquor dealers took advantage of illiterate Omahas by handing them ballot tickets with "Against Prohibition" on them.[44] Other sources claim that the Native men were bribed with liquor from white men.[40] Later, she lobbied for the Meilklejohn Bill, which would outlaw the sale of alcohol to any recipient of allotted land whose property was still held in trust by the government. The Meiklejohn Bill became law in January 1897 but proved nearly impossible to enforce.[45]

Picotte continued to fight against alcohol for the rest of her life, and when the peyote religion arrived on the Omaha reservation in the early 1900s, she gradually accepted it as a means of fighting alcoholism, as many members of the peyote religion were able to reconnect with their spiritual traditions and reject alcoholic ambitions.[46]

Sanitation, tuberculosis, and other public health reforms

[edit]

Beyond temperance, Picotte worked on public health issues in the wider community, including school hygiene, food sanitation, and efforts to combat the spread of tuberculosis.[47] She served on the health board of the town of Walthill, and was a founding member of the Thurston County Medical Society in 1907.[48]

Picotte was also the chair of the state health committee of the Nebraska Federation of Women's Clubs during the first decade of the 20th century.[49] As chair, she spearheaded efforts to educate people about public health issues, particularly in the schools, believing that the key to fighting disease was education.[50] From her time in medical school onward, she also campaigned for the building of a hospital on the reservation. It was finally completed in 1913 and later named in her honor.[51] This was the first privately funded hospital on a reservation.[40]

Her most important crusade was against tuberculosis, which killed hundreds of Omaha, including her husband Henry in 1905.[52] In 1907, she wrote to the Indian Office to try to persuade them to help, but they turned her down, blaming a lack of funding.[52] Because there was not yet a cure available, Picotte advocated cleanliness, fresh air, and the eradication of houseflies, which were believed to be major carriers of TB.[53]

Picotte's willingness to engage in political action carried over into areas other than public health. After the death of her husband, she became increasingly active in the campaigns against extending the trust period for the Omaha. She was a delegate to the Secretary of the Interior, protesting changes in the supervision of the Omaha.[54]

Political involvement and the issue of allotment

[edit]Struggles with inheritance

[edit]

The issue of land allotment came up again when Picotte's husband Henry died in 1905. He left about 185 acres of land in South Dakota to her and their two sons, Pierre and Caryl, but complications had arisen in claiming and selling it.[55] At the time of Henry's death, the land was still held in trust by the government, and in order to receive the monies from its sale, his heirs had to prove competency.[55] Minors, such as Picotte's sons, had to have a legal guardian who could prove competency on their behalf.[55]

The process of gaining the monies owed to them was long and arduous, and Picotte had to send letter after letter to the Indian Office to get them to recognize her as a competent individual in order to receive her portion of the inheritance, which R. J. Taylor, the agent on the Yankton reservation, finally granted to her in 1907, nearly two years after her husband's death.[56] However, gaining her children's inheritance proved to be a harder struggle. Another relative, Peter Picotte, was the legal guardian of her sons' land, because it was in another state, but he refused to consent to the sale of the land.[56]

Picotte responded by bombarding Commissioner Leupp, head of the Indian Office, with letters, painting Peter Picotte as a drunk and R. J. Taylor as intransigent and incompetent, while making a case for herself as the best manager of her sons' money.[57] This time, her letters received attention, and the Indian Office responded to her within a week of the original letters, informing her that Taylor had been ordered to ignore Peter Picotte's objections.[citation needed]

Picotte invested this money in rental properties, and was able to use that income to support herself and her sons.[58] This was not the end of her fights with the bureaucracy of the federal government, however. Her children inherited land from some Sioux relatives of her husband, and she entered into another battle with the bureaucracy, which ended positively in 1908.[59]

Action for the community

[edit]Picotte's struggles with the bureaucracy of allotment continued on behalf of other members of her community. In her position as a doctor, Picotte had gained the trust of her community, and her role as a local leader had expanded from letter writer/interpreter to defender of Omaha land interests.[59] She sought to help other Omaha who wanted to sell their lands and gain control of the monies owed to them, and she also tried to help resolve situations where whites took advantage of Indians who chose to lease land.[60]

Doing this work, she became increasingly aware and outraged at the land fraud committed by a syndicate of men on and around the Omaha reservation.[60] Picotte focused on the syndicate, which was made up of three white and two Omaha men who defrauded minors of their inheritances.[61] In a bizarre twist, Picotte, who had spent much of her life proclaiming that the Omaha had the same capacity for "civilization" as any white man, wrote to the Indian Office in 1909 to say that some of her people were too incompetent to protect themselves against the fraudsters and thus needed the continued guardianship of the federal government.[62] In 1910, she traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak with officials from the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), and told them that though most of the Omaha were perfectly competent to manage their own affairs, the Indian Office had stifled the development of business skills and knowledge of the white world among Indians, and thus the incompetence of a minority of Omaha was, in fact, the fault of the federal government.[63]

This argument was the product of her campaigns against the consolidation of the Omaha and Winnebago agencies, which had been suggested in 1904 and revived in 1910.[63] Picotte had been part of a movement among the Omaha opposing this consolidation, and used letters and harshly critical newspaper articles to get her point across to the OIA bureaucracy.[64] She argued that the unnecessary red tape created by the consolidation was nothing but an extra burden on the Omaha and was further proof that the OIA treated them like children, rather than as citizens ready to participate in a democracy.[65] She continued to work on her community's behalf until the end of her life, though much of that seemed to be in vain, as her people lost many of their ancestral lands and became more, not less, dependent on the OIA.[66]

Illness, death, and legacy

[edit]

Picotte suffered for most of her life from chronic illness. In medical school, she had been bothered by trouble breathing, and after a few years working on the reservation, she was forced to take a break to recover her health in 1892, as she suffered from chronic pain in her neck, head, and ears.[67] She recovered but became ill again in 1893, after a fall from her horse left her with significant internal injuries.[67] Over time, Picotte's condition caused her to go deaf.[18]

As Picotte aged, her health declined, and by the time that the new reservation hospital was built in Walthill in 1913, she was too frail to be its sole administrator.[51] By early March 1915, she was suffering greatly and died of bone cancer[68] on September 18, 1915. The next day, services by both the Presbyterian Church as well as the Amethyst Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star were performed.[18] She is buried in Bancroft Cemetery,[18] Bancroft, Nebraska near her husband, father, mother, sisters and half-brother.[citation needed]

Picotte's sons went on to live full lives. Caryl Picotte made a career in the United States Army and served in World War II, eventually settling in El Cajon, California.[69] Pierre Picotte lived in Walthill, Nebraska, for most of his life and raised a family of three children.[70]

In her career, Picotte served over 1,300 patients in a 450 square mile area.[11]

Tributes

[edit]The reservation hospital in Walthill, Nebraska, now a community center,[71] is named after Picotte and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1993. The hospital has also been named as one of the 11 most endangered places of 2018 by the National Trust.[72] Work is underway to raise funds for its restoration.[73]

An elementary school in western Omaha Nebraska is named after Picotte.[74]

On June 17, 2017, the 152nd anniversary of her birth, Google released a Google Doodle honoring Picotte.[75]

In 2018, a bust of Picotte was dedicated at the Martin Luther King Jr. Transportation Center in Sioux City.[76]

In 2019, a statue of La Flesche was dedicated as part of Hampton University's Legacy Park.[77]

On October 11, 2021, Nebraska's first officially recognized Indigenous Peoples' Day, a bronze sculpture of Picotte by Benjamin Victor was unveiled by her descendants on Lincoln's Centennial Mall. Judi gaiashkibos (national leader on Native American issues) was instrumental in elevating Picotte's legacy and the creation of the sculpture.[78]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Susan La Flesche Picotte First Indigenous Female Physician". Nebraska Studies. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ Speroff 2003, p. 109.

- ^ a b Agonito, Joseph (2016). Brave Hearts: Indian Women of the Plains. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 159. ISBN 9781493019069. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Swetland 1994, p. 203.

- ^ Johansen, Bruce Elliott (2010). Native Americans Today: A Biographical Dictionary. ABC-CLIO. p. 155. ISBN 9780313355547. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ Pedigo, Erin (April 2011). The Gifted Pen: the Journalism Career of Susette "Bright Eyes" La Flesche Tibbles (Master's). University of Nebraska Lincoln. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 25.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 31.

- ^ a b c "Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte". Changing the Face of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Hoxie 1984, p. 54.

- ^ Tony (1999), 40

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Mathes 1982, p. 503.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 50.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mathes, Valerie (1993). "Susan Laflesche Picotte.MD.: Nineteenth-Century Physician and Reformer". Great Plains Quarterly. 13 (3): 172–186. JSTOR 23531722.

- ^ a b c Tong 1999, p. 57.

- ^ Morantz-Sanchez (1985), 76

- ^ Tong (1999), 61

- ^ Tong (1999) 61

- ^ Mathes (1990), 8

- ^ a b Mathes 1990, p. 9.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Morantz-Sanchez 1985, p. 75.

- ^ Vaughn, Carson (March 1, 2017). "The Incredible Legacy of Susan La Flesche, the First Native American to Earn a Medical Degree". Smithsonian. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 84.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 86.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 85.

- ^ a b Diffendal 1994, p. 43.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 91.

- ^ Klein, Christopher. "Remembering the First Native American Woman Doctor". History. A+E Networks. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c Tong 1999, p. 94.

- ^ "Susan La Flesche's legacy lives on". Native Daughters. University of Nebraska Lincoln. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 100.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 102.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Pripas-Kapit, Sarah (Winter 2015). ""We Have Lived on Broken Promises": Charles A. Eastman, Susan La Flesche Picotte, and the Politics of American Indian Assimilation during the Progressive Era". Great Plains Quarterly. 35 (1): 51–78. doi:10.1353/gpq.2015.0009. S2CID 154097944.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 107.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 109.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 111.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Tong 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Tong 1997, p. 28.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 179.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 178.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 181.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 182.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 189.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 183.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 184.

- ^ Mathes 1982, p. 522.

- ^ a b c Tong 1999, p. 147.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 150.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 151.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 152.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 153.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 155.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 157.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 158.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 160.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 165.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 166.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 175.

- ^ a b Tong 1999, p. 122.

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 190.

- ^ C.A.Picotte (2018) p.197

- ^ Tong 1999, p. 198.

- ^ "Picotte Memorial Hospital, featured in National American Indian Heritage Month – A National Register of Historic Places Feature". Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Abourezk, Kevin (June 26, 2018). "Trailblazing tribal hospital lands on 'Most Endangered Historic Places' list". Indianz.Com.

- ^ Bureau, Paul Hammel World-Herald (February 25, 2018). "New effort launched to save hospital founded by Nebraskan who became nation's first Native American physician". Omaha.com. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

{{cite web}}:|author-last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Picotte's history in brief". picotte.ops.org. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ "Susan La Flesche Picotte Google doodle pays homage to 1st American Indian to earn her medical degree". June 17, 2017.

- ^ "Busts dedicated for five more community leaders in downtown Sioux City | State and regional". siouxcityjournal.com. October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ "Hampton University Unveils Newest Addition to Campus, Legacy Park". January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Picotte statue unveiled". www.1011now.com. October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cogan, Frances B. (1989). All-American Girl: The Ideal of Real Womanhood in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 082031062X.

- DeJong, David (1993). Promises of the Past: A History of Indian Education in the United States. Golden, CO: North American Press. ISBN 1555919057.

- Diffendal, Anne P. (January 1994). "The LaFlesche Sisters: Victorian Reformers in the Omaha Tribe". Journal of the West. 33 (1).

- Hoxie, Frederick (1984). A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803223234.

- Mathes, Valerie Sherer (1982). "Susan LaFlesche Picotte-Nebraska's Indian Physician, 1865-1915" (PDF). Nebraska History. 63 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- Mathes, Valerie Sherer (1990). "Nineteenth Century Women and Reform: The Women's National Indian Association". American Indian Quarterly. 14 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2307/1185003. JSTOR 1185003.

- Morantz-Sanchez, Regina Markell (1985). Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195036271.

- Speroff, Leon (2003). Carlos Montezuma, M.D. : a Yavapai American Hero : the Life and Times of an American Indian, 1866–1923. Portland, Oregon: Arnica Publishing. ISBN 0972653546.

- Starita, Joe (2016). A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche Overcame Racial and Gender Inequality to Become America's First Indian Doctor. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-08534-4.

- Swetland, Mark (August 1994). ""Make Believe White Men" and the Omaha Land Allotments of 1871–1900". Great Plains Research. 4 (2).

- Tong, Benson (1997). "Allotment, Alcohol and the Omahas". Great Plains Quarterly. 17 (1): 19–33. JSTOR 23531946.

- Tong, Benson (1999). Susan LaFlesche Picotte, M.D.: Omaha Indian Leader and Reformer. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806131403.

Further reading

[edit]- Enss, Chris (2006). The doctor wore petticoats: women physicians of the old West (1st ed.). Guilford, Conn.: TwoDot. ISBN 9780762735662.

- Bataille, Gretchen M., Laurie Lisa (2005). Native American women: a biographical dictionary. New York: Taylor & Francis e-library.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Starita, Joe (2016). A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche Overcame Racial and Gender Inequality to Become America's First Indian Doctor. New York: St. Martin's Press.

External links

[edit]- Susan La Flesche Picotte at Find a Grave

Media related to Susan La Flesche Picotte at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Susan La Flesche Picotte at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch