Sweetheart of the Rodeo

| Sweetheart of the Rodeo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | August 1968[nb 1] | |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 32:35 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Gary Usher | |||

| The Byrds chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Sweetheart of the Rodeo | ||||

| ||||

Sweetheart of the Rodeo is the sixth studio album by the American rock band the Byrds, released in August 1968 by Columbia Records.[9] Recorded with the addition of country rock pioneer Gram Parsons, it became the first album widely recognized as country rock[5] as well as a seminal progressive country album,[6] and represented a stylistic move away from the psychedelic rock of the band's previous LP, The Notorious Byrd Brothers.[10] The Byrds had occasionally experimented with country music on their four previous albums, but Sweetheart of the Rodeo represented their fullest immersion into the genre up to that point in time.[11][12][13] The album was responsible for bringing Parsons, who had joined the Byrds in February 1968 prior to the start of recording, to the attention of a mainstream rock audience for the first time.[13][14] Thus, the album is an important chapter in Parsons' crusade to make country music fashionable for a young audience.[15]

The album was conceived as a history of 20th century American popular music, encompassing examples of country music, jazz and rhythm and blues, among other genres.[11] However, steered by the passion of the little-known Parsons, this concept was abandoned early on and the album instead became purely a country record.[11][16] The recording of the album was divided between sessions in Nashville and Los Angeles, with contributions from session musicians including Lloyd Green, John Hartford, JayDee Maness, and Clarence White.[17] Tension developed between Parsons and the rest of the band, guitarist Roger McGuinn especially, and some of Parsons' vocals were re-recorded, partly due to legal issues.[18][19] By the time the album was released, Parsons had left the band.[20] The Byrds' move away from rock and pop towards country music elicited a great deal of resistance and hostility from the ultra-conservative Nashville country music establishment, who viewed the Byrds as a group of hippies attempting to subvert country music.[16]

Upon its release, the album reached number 77 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, but failed to reach the charts in the United Kingdom.[21][22] Two attendant singles were released during 1968, "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere", which achieved modest success, and "I Am a Pilgrim", which failed to chart.[22][23] The album received mostly positive reviews in the music press, but the band's shift away from psychedelic music alienated much of its pop audience.[24] Despite being the least commercially successful Byrds' album to date upon release, Sweetheart of the Rodeo is today considered to be a seminal and highly influential country rock album.[11]

Background (January–March 1968)

[edit]The initial concept by Roger McGuinn for the album that would become Sweetheart of the Rodeo was to expand upon the genre-spanning approach of the Byrds' previous LP, The Notorious Byrd Brothers, by recording a double album overview of the history of American popular music.[16] The planned album would begin with bluegrass and Appalachian music, then move through country and western, jazz, rhythm and blues, and rock music, before culminating with futuristic proto-electronica featuring the Moog modular synthesizer.[16]

But with a U.S. college tour to promote The Notorious Byrd Brothers looming, a more immediate concern was the recruitment of new band members.[18] David Crosby and Michael Clarke had been dismissed from the band in late 1967, leaving Roger McGuinn as de facto leader of the Byrds, along with Chris Hillman, the only other remaining member of the band.[15][25] To address this problem, McGuinn hired Hillman's cousin, Kevin Kelley (formerly a member of the Rising Sons), as the band's new drummer,[11] and it was this three-piece line-up, with McGuinn on guitar and Hillman on bass, that embarked on the early 1968 college tour.[26] It soon became apparent, however, that the Byrds were having difficulty performing their studio material live as a trio, and so it was decided that a fourth member was required.[26] McGuinn, with an eye still on his envisaged American music concept album, felt that a pianist with a jazz background would be ideal for the group.[15]

A candidate was found by Larry Spector, the band's business manager, in the shape of 21-year-old Gram Parsons.[18] Parsons, a marginal figure in the L.A. music scene, had been acquainted with Hillman since 1967 and he auditioned for the band as a piano player in February 1968.[16] His faux-jazz piano playing[26] and genial personality at audition was enough to impress both McGuinn and Hillman; so Parsons was recruited as the fourth member of the band, although he quickly switched to playing guitar instead of piano.[15] Although Parsons and Kelley were full members of the Byrds, they received a salary from McGuinn and Hillman and did not sign with Columbia Records when the Byrds' recording contract was renewed on February 29, 1968.[18]

Unbeknownst to McGuinn or Hillman, Parsons had his own musical agenda in which he planned to marry his love of traditional country music (which he saw as the purest form of American music) with youth culture's passion for rock.[27] He had already successfully attempted this fusion as a member of the little-known International Submarine Band, on the album Safe at Home, but Parsons' new status as a Byrd offered him an international stage from which to launch his bid to reclaim country music for his generation.[14][15]

Following his recruitment, Parsons began to lure Hillman away from McGuinn's concept album idea and towards a blend of what Parsons would later term "Cosmic American Music".[16] In essence, this was a hybrid of various roots music forms, primarily oriented towards honky tonk country music but also encompassing American folk, soul, rhythm and blues, rock ’n’ roll and contemporary rock.[15] Hillman, who had come from a musical background firmly rooted in bluegrass, had successfully persuaded the Byrds to incorporate country influences into their music in the past, beginning with the song "Satisfied Mind" on their 1965 album, Turn! Turn! Turn![15] Many of Hillman's songs on the Younger Than Yesterday and The Notorious Byrd Brothers albums also had a pronounced country feel, with several featuring Clarence White (a renowned bluegrass guitar player and session musician) on lead guitar, rather than McGuinn.[28][29] During time spent singing old country songs with Parsons, Hillman became convinced that Parsons' concept of a country-oriented version of the Byrds could work.[18]

Parsons' passion for his country rock vision was so contagious that he convinced McGuinn to abandon plans for the Byrds' next album and follow Parsons' lead in recording a country rock album.[26] Parsons also persuaded McGuinn and Hillman to record the album in the country music capital of Nashville, Tennessee,[18] as Bob Dylan had done for his Blonde On Blonde and John Wesley Harding albums.[30] Although McGuinn had reservations about the band's new direction, he decided that such a move could expand the already declining audience of the group.[16] After long-time Byrds' producer Gary Usher, who had little interest in producing McGuinn's concept album, indicated a preference for the country concept, McGuinn acquiesced.[15] On March 9, 1968, the band decamped to Columbia's recording facility in Nashville to begin recording sessions for Sweetheart of the Rodeo.[16]

Recording (March–May 1968)

[edit]Between March 9 and March 15, 1968, the band, accompanied by several prominent session musicians, recorded multiple takes of eight songs at Columbia's Studio A in the Music Row area of Nashville.[17][31] Recording sessions for the album continued from April 4 through May 27, 1968, at Columbia Studios in Hollywood, with a further seven songs recorded during these sessions and finishing touches applied to many of the tracks recorded in Nashville.[16][17]

The songs that the Byrds recorded for the album included "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" and "Nothing Was Delivered", two country-influenced Dylan covers from his then-unreleased Basement Tapes sessions.[32] Despite the change in musical style that the Sweetheart of the Rodeo album represented, the inclusion of two Dylan covers provided a link with their previous folk-rock incarnation, when Dylan's material had been a mainstay of their repertoire.[32] The Byrds also recorded a trio of classic country songs for the album: the traditional "I Am a Pilgrim", which Merle Travis popularized in the late-1940s;[33] the Cindy Walker-penned "Blue Canadian Rockies", which had been sung by Gene Autry in the 1952 film of the same name;[15][34] and "The Christian Life", written by the Louvin Brothers, which was the antithesis of a traditional rock song with its gentle lyrics extolling the simple pleasures of Christianity as a lifestyle.[35]

The band supplemented these older country standards and Dylan covers with two contemporary country songs: Merle Haggard's maudlin convict's lament, "Life in Prison"; and Luke McDaniel's "You're Still On My Mind", a sorrowful tale of a heartbroken drunkard failing to find solace at the bottom of a bottle.[36] Additionally, the Byrds gave William Bell's Stax hit, "You Don't Miss Your Water", a country flavored make-over, highlighted by the band's trademark crystal clear harmonies and contributions from JayDee Maness and Earl P. Ball, on pedal steel guitar and honky-tonk piano respectively.[36] With its fusion of country and soul, "You Don't Miss Your Water" was a perfect example of what Parsons would later define, with his self-coined phrase, as "Cosmic American Music".[36]

Lacking any country songs of his own, McGuinn delved into his pre-Byrds folk song repertoire instead, contributing Woody Guthrie's "Pretty Boy Floyd", a romanticized portrayal of the real-life folk hero and outlaw.[36] The March 12, 1968 recording session that produced "Pretty Boy Floyd" saw McGuinn attempting to play the song's banjo accompaniment, but feeling dissatisfied with his efforts, he ceded the part to session player John Hartford.[16] The Byrds also recorded a Kelley original, "All I Have Are Memories",[16] Tim Hardin's "You Got a Reputation", and the traditional song, "Pretty Polly", but none of these songs were selected for the final Sweetheart of the Rodeo album.[32]

Parsons brought three of his songs to the recording sessions: "Lazy Days", "One Hundred Years from Now" and "Hickory Wind", the latter of which had been written by Parsons and former International Submarine Band member, Bob Buchanan, during an early 1968 train ride from Florida to Los Angeles.[32] "One Hundred Years from Now" has a quicker tempo than most of the material on Sweetheart of the Rodeo and functions as a speculation on current human vanities and how they might be viewed by successive generations.[36] The Chuck Berry-influenced "Lazy Days" was not included in the final album, but was re-recorded by Parsons and Hillman's later band, the Flying Burrito Brothers, for their 1970 album, Burrito Deluxe.[37]

Nashville reaction and touring

[edit]

Upon completion of the Music Row recording sessions, the band ended their stay in Nashville with an appearance at the Grand Ole Opry at Ryman Auditorium (introduced by future "outlaw" country star Tompall Glaser), on March 15, 1968.[18] The band was greeted with derision by the conservative audience because they were the first group of hippie "longhairs" to play at the venerable country music establishment.[16] In fact, the Byrds had all had their hair cut shorter than they normally wore it, specifically for their appearance at the Grand Ole Opry, but this did nothing to appease their detractors in the audience.[16] The Byrds opened with a rendition of Merle Haggard's "Sing Me Back Home", which was met with derisive heckling, booing, and mocking calls of "tweet, tweet" from the hostile Opry audience.[16] Any hope of salvaging the performance was immediately destroyed when Parsons, rather than singing a song announced by Glaser, launched into a rendition of "Hickory Wind" dedicated to his grandmother.[16] This deviation from protocol stunned Opry regulars such as Roy Acuff, and embarrassed Glaser, ensuring that the Byrds would never be invited back to play on the show.[18]

Nearly as disastrous was the group's appearance on the WSM program of legendary Nashville DJ, Ralph Emery, who mocked his guests throughout the interview and initially refused to play an acetate of "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere".[38] Eventually playing the record, he dismissed it over the air and in the presence of the band as being mediocre.[38] Clearly upset by their treatment, Parsons and McGuinn would make Emery the subject of their song, "Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man", which was written by the pair in London in May 1968.[39] The song appeared on the Byrds' next album, Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde, although this recording did not feature Parsons because he had left the band by this time.[40]

After returning from Nashville, the band played a handful of concerts throughout the Los Angeles area with the addition of pedal steel guitarist JayDee Maness, who had played on several tracks on the album and Parsons' earlier Safe at Home.[18] Throughout April 1968, McGuinn came under considerable pressure from Parsons to recruit Maness as a full member of the Byrds, so that the band's new country material would sound authentic in concert, but McGuinn resisted, although Maness has stated in interview that he declined the invitation anyway.[16][18][41] Having failed to recruit Maness as a permanent member of the band, Parsons next recommended another pedal steel guitar player, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, but once again, McGuinn held firm.[18] Parsons' attempts to recruit new members and dictate the band's musical direction caused a power struggle within the band, with McGuinn finding his position as band leader challenged by Parsons, who was also pushing for a higher salary.[18] At one point Parsons even demanded that the album be billed as "Gram Parsons and the Byrds", a demand that was ignored by McGuinn and Hillman.[18]

In May 1968 the band embarked on a short European tour and while in England for concerts at the Middle Earth Club and Blaises, the Byrds met with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards who both expressed concern over the Byrds' intention to tour South Africa during the summer.[18] McGuinn remained undaunted regarding these concerns over the country's apartheid policies, having already received the blessing of South African singer Miriam Makeba.[18] He convinced the rest of the Byrds that a trip to South Africa would be an interesting experience.[42] This meeting between the Byrds and the two Rolling Stones would play an important part in Parsons' departure from the band two months later.[26]

Post-production

[edit]Upon the group's return to California, post-production work on the Sweetheart of the Rodeo album was disrupted when Parsons' appearance on the album was contested by Lee Hazlewood, who contended that the singer was still under contract to his LHI record label.[11] While the legal problems were being resolved, McGuinn replaced three of Parsons' lead vocals with his own singing, a move that still infuriated Parsons as late as 1973, when he told Cameron Crowe in an interview that McGuinn "erased it and did the vocals himself and fucked it up."[43] However, Parsons was still featured singing lead vocals on the songs "Hickory Wind", "You're Still on My Mind", and "Life in Prison".[32] There has been speculation that McGuinn's decision to re-record Parsons' lead vocals himself was not entirely motivated by the threat of legal action, but by a desire to decrease Parsons' presence on the album. According to producer Gary Usher:

McGuinn was a little bit edgy that Parsons was getting a little bit too much out of this whole thing...He didn't want the album to turn into a Gram Parsons album. We wanted to keep Gram's voice in there, but we also wanted the recognition to come from Hillman and McGuinn, obviously. You just don't take a hit group and interject a new singer for no reason...There were legal problems but they were resolved and the album had just the exact amount of Gram Parsons that McGuinn, Hillman and I wanted.[19][44]

The three songs that had their lead vocals replaced by McGuinn were "The Christian Life", "You Don't Miss Your Water", and "One Hundred Years from Now", with the last featuring McGuinn and Hillman sharing vocals on the final album version.[19][41] However, Parsons' lead vocals weren't completely eradicated from these songs and can still be faintly heard, despite having either McGuinn or Hillman's voice overdubbed on them.[15][19] The master recordings of these three songs, with their original Parsons' vocals restored to full prominence, were finally issued as part of The Byrds box set in 1990.[45] These same master recordings, featuring Parsons' lead vocals, were also included as bonus tracks on disc one of the 2003 Legacy Edition of Sweetheart of the Rodeo.[16]

With the legal problems surrounding Parsons' appearance on the album resolved, the Byrds returned to England for an appearance at the Royal Albert Hall on July 7, 1968.[20] Following the concert, Parsons announced that he would not be accompanying the band on their imminent tour of South Africa in protest over the country's policies of apartheid (a policy that did not cease until 1994).[16] Both McGuinn and Hillman doubted the sincerity of Parsons' protest, believing instead that Parsons had used the apartheid issue as a convenient excuse to leave the band and stay in England to hang out with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.[26] Consequently, by the time Sweetheart of the Rodeo was released in August 1968, Parsons had been an ex-member of the Byrds for almost eight weeks.[20] Following the South African tour, McGuinn and Hillman replaced Parsons with longtime Byrd-in-waiting Clarence White,[46] and Kevin Kelley was dismissed from the band soon after.[11] In total, the McGuinn, Hillman, Parsons, and Kelley line-up of the Byrds had lasted a mere five months.[16]

Release and reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork Media | 9.0/10 (1997)[49] 9.7/10 (2003)[50] |

| Rolling Stone | (mixed)[51] |

| Stylus | A−[52] |

| Uncut | |

Sweetheart of the Rodeo was released on August 30, 1968, in the United States (catalogue item CS 9670) and September 27, 1968, in the UK (catalogue item 63353).[9] However, there is some doubt about the American release date, as the album was first listed on the U.S. charts in the August 24 issue of Cashbox magazine and therefore must have been on sale a few weeks earlier than August 30.[3]

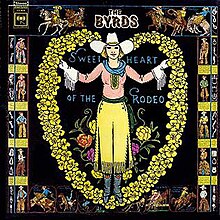

It was the first Byrds LP to be issued exclusively in stereo in the United States, although the album was released in both mono and stereo variations in the United Kingdom.[9] Columbia Records launched an accompanying print advertising campaign proclaiming, "This Country's for the Byrds" and featuring the tag line "Their message is all country … their sound is all Byrds."[16] In spite of this, Sweetheart of the Rodeo only reached number 77 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, during a chart stay of ten weeks,[21] and failed to chart in the United Kingdom at all.[22] The lead single from the album was a cover of Bob Dylan's "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere", which was released on April 2, 1968, climbing to number 75 on the Billboard Hot 100[23] and number 45 in the UK charts.[22] A second single from the album, "I Am a Pilgrim", was released on September 2, 1968,[9] but failed to chart.[22][23] The album cover artwork was adapted by Geller and Butler Advertising from elements of the 1932 poster The American Cowboy Rodeo/Evolution of the Cowboy by Uruguyan artist Jo Mora.[16][54]

Despite receiving generally favorable reviews from the critics, the country-rock style of Sweetheart of the Rodeo was such a radical departure from the band's previous sound that large sections of the group's counterculture following were alienated by its contents, resulting in the lowest sales of any Byrds album up to that point.[24][36] Barry Gifford, in the August 1968 edition of Rolling Stone magazine, said of the album: "The new Byrds do not sound like Buck Owens & his Buckaroos. They aren't that good. The material they've chosen to record, or rather, the way they perform the material, is simple, relaxed and folky. It's not pretentious, it's pretty. The musician-ship is excellent."[55] Gifford added that "The Byrds have made an interesting album. It's really very uninvolved and not a difficult record to listen to. It ought to make the 'Easy-Listening' charts. 'Bringing it all back home' has never been an easy thing to do."[55] Rolling Stone praised the album in a September 1968 issue, with Jon Landau writing: "The Byrds, in doing country as country, show just how powerful and relevant unadorned country music is to the music of today." Landau added that "they leave just enough rock in the drums to let you know that they can still play rock & roll."[56] In a 1969 article for The New York Times, Robert Christgau described Sweetheart of the Rodeo as "a bittersweet tribute to country music".[57]

Among the less favorable contemporary critiques, a Melody Maker reviewer dismissed the album as "Not typical Byrds music, which is rather a pity."[16] Writing in Crawdaddy! just before he withdrew from city life and temporarily retired from music journalism, Paul Williams dismissed both the Byrds' album and Music from Big Pink for providing "wonderful stifling inertia" that is only good for relaxation, writing: "I guess this isn't the summer to look to be rescued by music."[58] Robert Shelton of The New York Times similarly commented that "The latest Byrds album adheres to most of the 'rules of the game' about country sound, and yet, sad to say, to this old fan of the Byrds, the album is a distinguished bore."[10]

In more recent years, AllMusic critic Mark Deming remarked in his review of the album that "no major band had gone so deep into the sound and feeling of classic country (without parody or condescension) as the Byrds did on Sweetheart; at a time when most rock fans viewed country as a musical "L'il Abner" routine, the Byrds dared to declare that C&W could be hip, cool, and heartfelt."[12] Alexander Lloyd Linhardt, reviewing the album for Pitchfork Media, described it as "a blindingly rusty gait through parched weariness and dusted reverie. It's not the natural sound of Death Valley or Utah, but rather, a false portrait by people who wished it was, which makes it even more melancholy and charismatic."[50] Journalist Matthew Weiner commented in his review for Stylus that "Thirty-five years after it startled Byrds fans everywhere with its Podunk proclivities, Sweetheart remains a particularly fascinating example of two musical ships passing in the night, documenting both Parsons’ transformation into a visionary country-rock auteur and a pop band's remarkable sense of artistic risk."[52]

The Byrds' biographer, Johnny Rogan, has said that the album "stood alone as a work almost completely divorced from the prevailing rock culture. Its themes, mood and instrumentation looked back to another era at a time when the rest of America was still recovering from the recent assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy."[36] Ultimately, the Byrds' experimentation with the country genre on Sweetheart of the Rodeo was slightly ahead of its time, to the detriment of the band's commercial fortunes, as the international success of country rock-flavored bands like the Eagles, America and Dr. Hook & The Medicine Show during the 1970s demonstrated.[36]

Legacy

[edit]Released at a time when the Byrds' surprising immersion in the world of country music coincided with their declining commercial appeal, Sweetheart of the Rodeo was an uncommercial proposition.[11] However, the album has proved to be a landmark, serving not only as a blueprint for Parsons' and Hillman's the Flying Burrito Brothers, but also for the entire nascent 1970s Los Angeles country rock movement. The album was also influential on the outlaw country and new traditionalist movements, as well as the so-called alternative country genre of the 1990s and early 21st century.[11][15] Among fans of the Byrds, however, opinion is often sharply divided regarding the merits of the album, with some seeing it as a natural continuation of the group's innovations, and others mourning the loss of the band's trademark Rickenbacker guitar jangle and psychedelic experimentation.[59] Nonetheless, Sweetheart of the Rodeo is widely considered by critics to be the Byrds' last truly influential album.[15][60]

Although it was not the first country rock album,[12] Sweetheart of the Rodeo was the first album widely labeled as country rock to be released by an internationally successful rock act,[5][59][61] pre-dating the release of Bob Dylan's Nashville Skyline by over six months.[62][63] The first bona fide country rock album is often cited as being Safe at Home by Parsons' previous group, The International Submarine Band.[12][14][64] However, the genre's antecedents can be traced back to the Rockabilly music of the 1950s, the Beatles' covers of Carl Perkins and Buck Owens' material on Beatles For Sale and Help!, as well as the stripped down arrangements of Dylan's John Wesley Harding album and the Byrds' own forays into country music on their pre-Sweetheart albums.[62][65][66] The Band's debut album, Music from Big Pink, released in July 1968, was also influential on the genre, but it was Sweetheart of the Rodeo that saw an established rock band playing pure country music for the first time.[59][61][62]

The album was included in "A Basic Record Library" of 1950s and 1960s recordings, published in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981).[67] In 2003, the album was ranked number 117 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[68] 120 in a 2012 revised list,[69] and 274 in a 2020 revised list.[70] Stylus Magazine named it their 175th favorite album of all time also in 2003.[71] It was voted number 229 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums 3rd Edition (2000).[72]

Sweetheart of the Rodeo went on to inspire the name of the 1980s country duo, Sweethearts of the Rodeo, who paid tribute to the Byrds' album with the sleeve of their 1990 album, Buffalo Zone.[73]

In 2018, Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman reunited for a U.S. tour celebrating the 50th anniversary of Sweetheart of the Rodeo.[74] The duo, who were backed on the tour by Marty Stuart and his Fabulous Superlatives, performed all of the songs from the album and told stories about its creation.[75] A live album of recordings from the 50th Anniversary concerts was released for Record Store Day 2024.[76]

Track listing

[edit]| # | Title | Writer | Lead vocals | Guest musicians/band contributions beyond usual instruments[77] | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side 1 | |||||

| 1. | "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" | Bob Dylan | McGuinn | Lloyd Green (pedal steel guitar), Gram Parsons (organ) | 2:33 |

| 2. | "I Am a Pilgrim" | traditional, arranged Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman | Hillman | John Hartford (fiddle), Roy "Junior" Huskey (double bass), Roger McGuinn (banjo), Chris Hillman (acoustic guitar) | 3:39 |

| 3. | "The Christian Life" | Charles Louvin, Ira Louvin | McGuinn | JayDee Maness (pedal steel guitar), Clarence White (electric guitar) | 2:30 |

| 4. | "You Don't Miss Your Water" | William Bell | McGuinn | Earl P. Ball (piano), JayDee Maness (pedal steel guitar) | 3:48 |

| 5. | "You're Still on My Mind" | Luke McDaniel | Parsons | Earl P. Ball (piano), JayDee Maness (pedal steel guitar) | 2:25 |

| 6. | "Pretty Boy Floyd" | Woody Guthrie | McGuinn | Roy "Junior" Huskey (double bass), John Hartford (acoustic guitar, banjo, fiddle), Chris Hillman (mandolin) | 2:34 |

| Side 2 | |||||

| 1. | "Hickory Wind" | Gram Parsons, Bob Buchanan | Parsons | John Hartford (fiddle), Lloyd Green (pedal steel guitar), Roger McGuinn (banjo), Gram Parsons (piano) | 3:31 |

| 2. | "One Hundred Years from Now" | Gram Parsons | McGuinn, Hillman | Barry Goldberg (piano), Lloyd Green (pedal steel guitar), Clarence White (electric guitar) | 2:40 |

| 3. | "Blue Canadian Rockies" | Cindy Walker | Hillman | Clarence White (electric guitar), Gram Parsons (piano) | 2:02 |

| 4. | "Life in Prison" | Merle Haggard, Jelly Sanders | Parsons | Earl P. Ball (piano), JayDee Maness (pedal steel guitar) | 2:46 |

| 5. | "Nothing Was Delivered" | Bob Dylan | McGuinn | Lloyd Green (pedal steel guitar), Gram Parsons (piano, organ) | 3:24 |

Singles

[edit]- "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" b/w "Artificial Energy" (Columbia 44499) April 2, 1968 (US #75, UK #45)

- "I Am a Pilgrim" b/w "Pretty Boy Floyd" (Columbia 44643) September 2, 1968

Personnel

[edit]Personnel adapted from The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited, So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-by-Day (1965–1973), the Sundazed Music website, Hot Burritos: The True Story of the Flying Burrito Brothers, and the 1997 CD liner notes.[11][17][19][78][79]

The credits on the original album erroneously include drummer Jon Corneal, who plays only on the outtake "Lazy Days". |

|

Release history

[edit]Sweetheart of the Rodeo was remastered at 20-bit resolution as part of the Columbia/Legacy Byrds series and reissued in an expanded form on March 25, 1997. The eight bonus tracks featured on this reissue include the outtakes "You Got a Reputation", "Lazy Days", and "Pretty Polly", as well as four previously unreleased rehearsal takes and an instrumental backing track for "All I Have Are Memories".[32] A hidden track on the CD features a 1968 Columbia Records radio advertisement for the album.

On September 2, 2003, a 2 CD Legacy Edition of Sweetheart of the Rodeo was released by Columbia/Legacy. This version of the album features additional outtakes, rehearsal versions, and the master takes of the songs that had their Parsons' lead vocals replaced, presented here with their Parsons' vocals intact.[81] Most of the alternate versions and rehearsal takes on disc two of the Legacy Edition feature Parsons singing songs that were later released with vocals by McGuinn on the original album. Also included on the Legacy Edition is an outtake from the album sessions called "All I Have Are Memories", written and sung by drummer Kevin Kelley.[52] In addition, the Legacy Edition of Sweetheart of the Rodeo includes six tracks performed by the International Submarine Band (Parsons' previous group).[81]

In 2007, Sundazed Music released a 7" single featuring previously unreleased alternate versions of "Lazy Days" and "You Got a Reputation" (titled "Reputation" on this release) that date from the Byrds' March 1968 recording sessions in Nashville.[78] These two alternate versions have not been issued on CD.

| Date | Label | Format | Country | Catalog | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 30, 1968 | Columbia | LP | US | CS 9670 | Original stereo release. |

| September 27, 1968 | CBS | LP | UK | 63353 | Original mono release. |

| S 63353 | Original stereo release. | ||||

| 1973 | Embassy | LP | UK | EMB 31124 | |

| 1976 | CBS | LP | UK | S 22040 | Double album stereo reissue with The Notorious Byrd Brothers. |

| 1982 | Columbia | LP | US | SBP 237803 | |

| 1987 | Edsel | LP | UK | ED 234 | |

| 1987 | Edsel | CD | UK | EDCD 234 | Original CD release. |

| 1990 | Columbia | CD | US | CK 9670 | |

| 1993 | Columbia | CD | UK | COL 468178 | |

| March 25, 1997 | Columbia/Legacy | CD | US | CK 65150 | Reissue containing eight bonus tracks and the remastered stereo album. |

| UK | COL 486752 | ||||

| 1999 | Simply Vinyl | LP | UK | SVLP 057 | Reissue of the remastered stereo album. |

| August 2003 | Sony | CD | Japan | MHCP-70 | Reissue containing eight bonus tracks and the remastered album in a replica LP sleeve. |

| September 2, 2003 | Columbia/Legacy | CD | US | C2K 87189 | Double CD reissue containing twenty-eight bonus tracks and the remastered stereo album. |

| UK | COL 510921 | ||||

| 2008 | Sundazed | LP | US | LP 5215 | |

| February 10, 2009 | Sony/Columbia | CD | US | 743323 | 2 CD reissue with Mr. Tambourine Man, containing eight bonus tracks and the remastered stereo album. |

1997 reissue bonus tracks

[edit]The final song on the 1997 reissue ("All I Have Are Memories") ends at 2:48; at 3:48 begins the hidden track "Radio Spot: Sweetheart of the Radio Album"

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "You Got a Reputation" | Tim Hardin | 3:08 |

| 13. | "Lazy Days" | Gram Parsons | 3:26 |

| 14. | "Pretty Polly" | trad, arr. Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman | 2:53 |

| 15. | "The Christian Life" (Rehearsal – Take #11) | Charles Louvin, Ira Louvin | 2:55 |

| 16. | "Life in Prison" (Rehearsal – Take #11) | Merle Haggard, Jelly Sanders | 2:59 |

| 17. | "You're Still on My Mind" (Rehearsal – Take #43) | Luke McDaniel | 2:29 |

| 18. | "One Hundred Years from Now" (Rehearsal – Take #2) | Gram Parsons | 3:20 |

| 19. | "All I Have Are Memories" (Instrumental) | Kevin Kelley | 4:47 |

2003 Legacy Edition bonus tracks

[edit]The 2003 CD reissue contains alternative versions of songs with Parsons singing lead, along with recordings by Parsons' pre-Byrds group, The International Submarine Band (tracks 1–6 on disc two).[82][83]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "All I Have Are Memories" (Kevin Kelley Vocal) | Kevin Kelley | 2:48 |

| 13. | "Reputation" | Tim Hardin | 3:09 |

| 14. | "Pretty Polly" | trad, arr. Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman | 2:55 |

| 15. | "Lazy Days" | Gram Parsons | 3:28 |

| 16. | "The Christian Life" (Gram Parsons Vocal) | Charles Louvin, Ira Louvin | 2:29 |

| 17. | "You Don't Miss Your Water" (Gram Parsons Vocal) | William Bell | 3:49 |

| 18. | "One Hundred Years from Now" (Gram Parsons Vocal) | Gram Parsons | 3:01 |

| 19. | "Radio Spot: Sweetheart of the Radio Album" | 0:58 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sum Up Broke" | Gram Parsons, John Nuese | 2:13 |

| 2. | "One Day Week" | Gram Parsons | 2:16 |

| 3. | "Truck Drivin' Man" | Terry Fell | 2:34 |

| 4. | "Blue Eyes" | Gram Parsons | 2:47 |

| 5. | "Luxury Liner" | Gram Parsons | 2:53 |

| 6. | "Strong Boy" | Gram Parsons | 2:01 |

| 7. | "Lazy Days" (Alternate Version) | Gram Parsons | 3:18 |

| 8. | "Pretty Polly" (Alternate Version) | trad, arr. Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman | 3:37 |

| 9. | "Hickory Wind" (Alternate "Nashville" Version – Take #8) | Gram Parsons, Bob Buchanan | 3:40 |

| 10. | "The Christian Life" (Rehearsal Version – Take #7 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Charles Louvin, Ira Louvin | 3:26 |

| 11. | "The Christian Life" (Rehearsal Version – Take #8 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Charles Louvin, Ira Louvin | 3:05 |

| 12. | "Life in Prison" (Rehearsal Version – Takes #1 & #2 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Merle Haggard, Jelly Sanders | 3:16 |

| 13. | "Life in Prison" (Rehearsal Version – Takes #3 & #4 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Merle Haggard, Jelly Sanders | 3:16 |

| 14. | "One Hundred Years from Now" (Rehearsal Version – Takes #12 & #13 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Gram Parsons | 3:58 |

| 15. | "One Hundred Years from Now" (Rehearsal Version – Takes #14 & #15 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Gram Parsons | 3:59 |

| 16. | "You're Still on My Mind" (Rehearsal Version – Take #13 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Luke McDaniel | 2:53 |

| 17. | "You're Still on My Mind" (Rehearsal Version – Take #48 – Gram Parsons Vocal) | Luke McDaniel | 2:38 |

| 18. | "All I Have Are Memories" (Alternate Instrumental – Take #17) | Kevin Kelley | 3:13 |

| 19. | "All I Have Are Memories" (Alternate Instrumental – Take #21) | Kevin Kelley | 3:07 |

| 20. | "Blue Canadian Rockies" (Rehearsal Version – Take #14) | Cindy Walker | 2:59 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Later writers cite August 30, 1968 as the American release date,[1][2] but the album appeared in the August 24 issue of Cashbox magazine, which featured the chart for the week beginning August 17.[3] Therefore the album must have been on sale earlier than August 30. An advertisement in the August 9 issue of The Plain Dealer indicated that the album was already on sale.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Rogan 1998, pp. 544–546.

- ^ Hjort 2008, p. 187.

- ^ a b "Cashbox magazine (cover dated August 24, 1968)" (PDF). worldradiohistory.com. Cashbox. p. 47. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- ^ "Super Session". The Plain Dealer. August 9, 1968. p. 29 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Chris Smith (2009). 101 Albums That Changed Popular Music. Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-537371-4.

- ^ a b Tunis, Walter (October 22, 2018). "Marty Stuart thankful opening for Chris Stapleton, 'the man carrying the flag for country music'". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ Blender Staff (May 2003). "500 CDs You Must Own Before You Die!". Blender. New York: Dennis Publishing Ltd. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Pitchfork Staff (August 22, 2017). "The 200 Best Albums of the 1960s". Pitchfork. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

Sweetheart of the Rodeo may not have made country cool, but it showed the volatility of two competing visions of Americana coexisting in the same space.

- ^ a b c d Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 544–546. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fricke, David. (1997). Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1997 CD liner notes).

- ^ a b c d e "Sweetheart of the Rodeo review". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ a b "Sweetheart of the Rodeo review". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ a b c Griffin, Sid. (1985). Safe at Home (1991 CD liner notes).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Sweetheart of the Rodeo". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Fricke, David (2003). Sweatheart of the Rodeo: Legacy Edition (CD booklet). The Byrds. New York City: Columbia/Legacy. pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b c d Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 624–625. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 250–261. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b c d e Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 162–176. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ a b c Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 177–187. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel. (2002). Top Pop Albums 1955–2001. Hal Leonard Corp. p. 121. ISBN 0-634-03948-2.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Tony. (2000). The Complete Book of the British Charts. Omnibus Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-7119-7670-8.

- ^ a b c Whitburn, Joel. (2008). Top Pop Singles 1955–2006. Record Research Inc. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-89820-172-7.

- ^ a b Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 269. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 146–153. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ a b c d e f "Gram Parsons and The Byrds: 1968". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ Brant, Marley. (1990). GP/Grievous Angel (1990 CD liner notes).

- ^ "Younger Than Yesterday". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2014-12-26. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "The Notorious Byrd Brothers". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2009-05-06. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ Heylin, Clinton. (1991). Dylan: Behind The Shades – The Biography. Viking Penguin. pp. 507–508. ISBN 0-670-83602-8.

- ^ "Dylan, Cash, and the Nashville Cats: A New Music City - Part 4: Artists That Followed". Country Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Rogan, Johnny. (1997). Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1997 CD liner notes).

- ^ "Artists Covered By The Byrds: R-Z". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2009-07-26. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "Soundtrack For Blue Canadian Rockies". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "The Christian Life review". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 270–274. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 442. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b "Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2009-08-19. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 281. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ "Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde review". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ a b Einarson, John with Hillman, Chris. (2008). Hot Burritos: The True Story Of The Flying Burrito Brothers. Jawbone Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-906002-16-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 263. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Fong-Torres, Ben. (1991). Hickory Wind: The Life and Times of Gram Parsons. Pocket Books. p. 94. ISBN 0-671-70514-8.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 260. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Fricke, David. (1990). The Byrds (1990 CD box set liner notes).

- ^ "Clarence White: With the Byrds and After, 1968–1973". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "The Byrds – Sweetheart of the Rodeo review". Blender. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195313734.

- ^ "The Byrds: Sweetheart of the Rodeo: Pitchfork Review". Archived from the original on 16 April 2004. Retrieved 2024-10-15.

- ^ a b "Sweetheart of the Rodeo (Legacy Edition) review". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on 2016-02-23. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ Gifford, Barry (14 September 1968). "Records". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "Sweetheart of the Rodeo (Legacy Edition) review". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ "The Byrds – Sweetheart of the Rodeo review". Uncut. Archived from the original on 2008-07-26. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ^ Lane, Baron (August 29, 2018). "5 Things You May Not Know About The Byrds' 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo'". Twang Nation. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- ^ a b "Sweetheart of the Rodeo review". Rolling Stone. 14 August 1968. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ Fricke, David. (2006). There Is a Season (2006 CD box set liner notes).

- ^ "The Byrds Have Flown – But Not Far". Robert Christgau: Dean of American Rock Critics. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ Lindberg, Ulf; Guomundsson, Gestur; Michelsen, Morten; Weisethaunet, Hans (2005). Rock Criticism from the Beginning: Amusers, Bruisers, and Cool-Headed Cruisers. New York, NY: Peter Lang. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8204-7490-8.

- ^ a b c "The Byrds Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "Sweetheart of the Rodeo: Legacy Edition review". PopMatters. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ a b "The Byrds And The Birth Of Country Rock". Yahoo! Music (originally published in ICE Magazine, August 2003). Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ a b c "The Complete Guide to Country Rock Part 3". Musictoob.com. Archived from the original on 2009-03-24. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ "The Byrds Biography". NME. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. (1999). Music USA: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides. p. 393. ISBN 1-85828-421-X.

- ^ "The Complete Guide to Country Rock Part 1". Musictoob.com. Retrieved 2009-11-10.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Complete Guide to Country Rock Part 2". Musictoob.com. Retrieved 2009-11-10.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "A Basic Record Library: The Fifties and Sixties". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899190251. Retrieved March 16, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "Top 101–200 Favourite Albums Ever". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on 2016-12-28. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 108. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ "Sweetheart of the Rodeo Album Cover Parodies". Am I Right. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "Byrds Co-Founders Plan 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo' 50th Anniversary Tour". Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone. 4 June 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ^ BrooklynVegan Staff. "Byrds members played 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo' & more at Town Hall (pics, setlist)". BrooklynVegan. Town Square Media. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- ^ "Sweetheart Of The Rodeo - RSD 2024". Rough Trade. Rough Trade. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ For this album the band's usual instruments are acoustic guitar (Roger McGuinn and Gram Parsons), electric bass (Chris Hillman), drums (Kevin Kelly), and vocals (Parsons, McGuinn and Hillman)

- ^ a b "The Byrds – Lazy Days/Reputation 7" single". Sundazed Music. Archived from the original on 2013-02-03. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ Einarson, John with Hillman, Chris. (2008). Hot Burritos: The True Story Of The Flying Burrito Brothers. Jawbone Press. pp. 55–69. ISBN 978-1-906002-16-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lane, Baron (August 29, 2018). "5 Things You May Not Know About The Byrds' 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo'". Twang Nation. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- ^ a b "Sweetheart of the Rodeo: Legacy Edition review". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ Personnel for these tracks, recorded prior to the sessions for Sweetheart of the Rodeo, are best ascertained from pages relating to The International Submarine Band and its lone album Safe at Home.

- ^ Jim Bessman, Billboard Picks Music, Vital Reissues, September 20, 2003. www.billboard.com. 20 September 2003. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hjort, Christopher (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- Rogan, Johnny (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch