Tea production in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (formerly called Ceylon) has a climate and varied elevation that allows for the production of both Camellia sinensis var. assamica and Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, with the assamica varietal holding the majority of production. Tea production is one of the main sources of foreign exchange for Sri Lanka, and accounts for 2% of GDP, contributing over US$1.3 billion in 2021 to the economy of Sri Lanka.[1] It employs, directly or indirectly, over 1 million people, and in 1995 directly employed 215,338 on tea plantations and estates. In addition, tea planting by smallholders is the source of employment for thousands whilst it is also the main form of livelihood for tens of thousands of families. Sri Lanka is the world's fourth-largest producer of tea. In 1995, it was the world's leading exporter of tea (rather than producer), with 23% of the total world export, and Sri Lanka ranked second on tea export earnings in 2020[2] after China. The highest production of 340 million kg was recorded in 2013, while the production in 2014 was slightly reduced to 338 million kg.[3] India has additionally guaranteed Sri Lanka a shipment of 65,000 metric tons of urea. Sri Lanka's troubled execution of an organic agriculture initiative had pushed the country perilously close to an agricultural crisis. Given the surge in global fertilizer prices, it is improbable that Sri Lanka could procure fertilizer at prevailing market rates.[4]

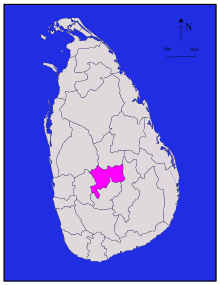

The humidity, cool temperatures, and rainfall of the country's central highlands provide a climate that favors the production of high-quality tea. On the other hand, tea produced in low-elevation areas such as Matara, Galle, and Ratanapura districts with high rainfall and warm temperature has a high level of astringent properties. The tea biomass production itself is higher in low-elevation areas. Such tea is popular in the Middle East. Sri Lanka produces mostly orthodox black teas but also produces CTC, white and green teas. The two types of green tea produced are the gunpowder type and sencha.[5] The industry was introduced to the country in 1867 by James Taylor, a British planter who arrived in 1852.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12] Tea planting under smallholder conditions has become popular in the 1970s. Most of Sri Lanka's export market is in the Middle East and Europe but there are also plenty of bidders worldwide for its specialty high-country-grown Nuwara Eliya teas.[5]

History

[edit]

The total population of Sri Lanka according to the census of 1871 was 2,584,780. The 1871 demographic distribution and population in the plantation areas are given below:[13]

| District | Total population | No. of estates | Estate population | % of population on estates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kandy District | 258,432 | 625 | 81,476 | 31.53 |

| Badulla District | 129,000 | 130 | 15,555 | 12.06 |

| Matale District | 71,724 | 111 | 13,052 | 18.2 |

| Kegalle District | 105,287 | 40 | 3,790 | 3.6 |

| Sabaragamuwa | 92,277 | 37 | 3,227 | 3.5 |

| Nuwara Eliya District | 36,184 | 21 | 308 | 0.85 |

| Kurunegala District | 207,885 | 21 | 2,393 | 1.15 |

| Matara District | 143,379 | 11 | 1,072 | 0.75 |

Growth and history of commercial production

[edit]

Registered tea production by elevation

[edit]Registered tea production in hectares and total square miles by elevation category in Sri Lanka, 1959–2000:[13]

| Year | High altitude hectares | Medium altitude hectares | Low altitude hectares | Total hectares | Total square miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | 74,581 | 66,711 | 46,101 | 187,393 | 723.5 |

| 1960 | 79,586 | 69,482 | 48,113 | 197,181 | 761.3 |

| 1961 | 76,557 | 97,521 | 63,644 | 237,722 | 917.8 |

| 1962 | 76,707 | 97,857 | 64,661 | 239,225 | 923.7 |

| 1963 | 76,157 | 95,691 | 65,862 | 237,710 | 917.8 |

| 1964 | 81,538 | 92,281 | 65,759 | 239,578 | 925.0 |

| 1965 | 87,345 | 92,806 | 60,365 | 240,516 | 928.6 |

| 1966 | 87,514 | 93,305 | 60,563 | 241,382 | 932.0 |

| 1967 | 87,520 | 93,872 | 60,945 | 242,337 | 935.7 |

| 1968 | 81,144 | 99,359 | 61,292 | 241,795 | 933.6 |

| 1969 | 81,092 | 98,675 | 61,616 | 241,383 | 932.0 |

| 1970 | 77,549 | 98,624 | 65,625 | 241,798 | 933.6 |

| 1971 | 77,936 | 98,624 | 65,625 | 242,185 | 935.1 |

| 1972 | 77,639 | 98,252 | 65,968 | 241,859 | 933.8 |

| 1973 | 77,793 | 98,165 | 66,343 | 242,301 | 935.5 |

| 1974 | 77,693 | 97,875 | 66,622 | 242,190 | 935.1 |

| 1975 | 79,337 | 98,446 | 64,099 | 241,882 | 933.9 |

| 1976 | 79,877 | 94,338 | 66,363 | 240,578 | 928.9 |

| 1977 | 79,653 | 94,835 | 67,523 | 242,011 | 934.4 |

| 1978 | 79,628 | 95,591 | 68,023 | 243,242 | 939.2 |

| 1979 | 78,614 | 97,084 | 68,401 | 244,099 | 942.5 |

| 1980 | 78,786 | 96,950 | 68,969 | 244,705 | 944.8 |

| 1981 | 78,621 | 96,853 | 69,444 | 244,918 | 945.6 |

| 1982 | 77,769 | 96,644 | 67,728 | 242,141 | 934.9 |

| 1983 | 71,959 | 90,272 | 67,834 | 230,065 | 888.3 |

| 1984 | 74,157 | 90,203 | 63,514 | 227,874 | 879.8 |

| 1985 | 74,706 | 89,175 | 67,769 | 231,650 | 894.4 |

| 1986 | 73,206 | 85,216 | 64,483 | 222,905 | 860.6 |

| 1987 | 72,773 | 84,445 | 64,280 | 221,498 | 855.2 |

| 1988 | 72,901 | 84,227 | 64,555 | 221,683 | 855.9 |

| 1989 | 73,110 | 84,062 | 64,938 | 222,110 | 857.6 |

| 1990 | 73,138 | 83,223 | 65,397 | 221,758 | 856.2 |

| 1991 | 73,331 | 82,467 | 65,893 | 221,691 | 856.0 |

| 1992 | 74,141 | 85,510 | 62,185 | 221,836 | 856.5 |

| 1994 | 51,443 | 56,155 | 79,711 | 187,309 | 723.2 |

| 1995 | 51,443 | 56,155 | 79,711 | 187,309 | 723.2 |

| 1996 | 52,272 | 56,863 | 79,836 | 188,971 | 729.6 |

| 1997 | 51,444 | 58,155 | 79,711 | 189,310 | 730.9 |

| 1998 | 51,444 | 58,155 | 79,711 | 189,310 | 730.9 |

| 2000 | 52,272 | 56,863 | 79,836 | 188,971 | 729.6 |

Main destination of Sri Lankan teas

[edit]The most important foreign markets for Sri Lankan tea are the former Soviet bloc countries of the CIS, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, Syria, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, UK, Egypt, Libya and Japan.[14]

The most important foreign markets for Sri Lankan tea are as follows, in terms of millions of kilograms and millions of pounds imported. The figures were recorded in 2000:[13]

| Country | Million kilograms | Million pounds | Total Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIS Countries | 57.6 | 127.0 | 20 |

| UAE | 48.1 | 106.0 | 16.7 |

| Russia | 46.1 | 101.6 | 16.01 |

| Syria | 21.5 | 47.4 | 7.47 |

| Turkey | 20.3 | 44.8 | 7.05 |

| Iran | 12.5 | 27.6 | 4.34 |

| Saudi Arabia | 11.4 | 25.1 | 3.96 |

| Iraq | 11.1 | 24.5 | 3.85 |

| UK | 10.2 | 22.5 | 3.54 |

| Egypt | 10.1 | 22.3 | 3.51 |

| Libya | 10.0 | 22.0 | 3.47 |

| Japan | 8.3 | 18.3 | 2.88 |

| Germany | 5.0 | 11.0 | 1.74 |

| Others | 23.7 | 52.2 | 8.23 |

| Total | 288 | 634.9 | 100 |

Revenue Statistics

[edit]| Year | Total Export Revenue of Tea (in million. US$) [15][16][17] |

|---|---|

| 2019 | |

| 2020 | |

| 2021 | |

| 2022 | |

| 2023 | |

| 2024 |

Branding

[edit]

The Sri Lanka Tea Board is the legal proprietor of the lion logo of Ceylon tea. The logo has been registered as a trademark in many countries. To appear the Lion logo on a tea pack, it must meet four criteria.

- The Lion Logo can only be used on consumer packs of Ceylon tea.

- The packs must contain 100 percent of pure Ceylon tea.

- The packaging should be done only in Sri Lanka.

- The brands which employ the Lion logo should meet the quality standards set by the Sri Lanka Tea Board.[18]

The logo is considered to be a "known sign of high quality" around the world.[19] The Sri Lanka Tea board signed an agreement to sponsor Sri Lanka national cricket team and Sri Lanka women's national cricket team in their overseas tours for US$4 million for three years.[20]

Research

[edit]The Tea Research Institute

[edit]The Tea Research Ordinance was enacted by Parliament in 1925 and the Tea Research Institute (TRI) was founded. It is at present the only national body in the country that generates and disseminates new research and technology related to the processing and cultivation of tea.[21]

Beginning in the early 1970s, two researchers from the National Institute of Dental Research in Bethesda, Maryland, USA conducted a series of research projects in which they arranged a longitudinal study group of a large number of Tamil tea labourers who worked at the Dunsinane and Harrow Tea Estates, 80 kilometres (50 mi) from Kandy. This landmark study was possible because the population of tea labourers were known to have never employed any conventional oral hygiene measures, thereby providing some insight into the natural history of periodontal disease in man.[22]

Sustainability standards and certifications

[edit]There are several organisations, both international and local, that promote and enforce sustainability standards and certifications about tea in Sri Lanka.

Among the international organisations that operate within Sri Lanka are Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, UTZ Certified, and Ethical Tea Partnership. The Small Organic Farmers' Association (SOFA) is a local organisation dedicated to organic farming.

Gallery

[edit]- Tea plantations in Wewalthalawa

- Tea plantations near Haputale, Uva

- Tea plantations in Nuwara Eliya

- Picking tea leaves

- Tea leaves

- Tea harvester in Sri Lanka

See also

[edit]- Akbar Tea

- Dilmah

- George Steuart Group (Steuarts Tea, 1835 Steuarts Ceylon)

- Heladiv

- Island Tea

- Loolecondera

- Mlesna

- Thomas Lipton

- Tea production in Azerbaijan

- Tea production in Bangladesh

- Tea production in Indonesia

- Tea production in Nepal

- Tea production in Kenya

- Tea production in Uganda

- Tea production in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Nadeera, Dilshan. "Lankan tea exports earned $ 1.3 Bn in 2021". Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Leading tea exporting countries worldwide in 2020". Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 2014, Annual Report, http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/10_pub/_docs/efr/annual_report/AR2014/English/content.htm Archived 2015-08-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Indian Assistance to Sri Lanka: Lifeline or Chokehold?". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b Smith, Krisi (2016). World Atlas of Tea. Great Britain: Mitchell Beazley. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-78472-124-4.

- ^ "TED Case Studies – Ceylon Tea". American University, Washington, DC. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Sri Lanka tops tea sales". BBC. 1 February 2002. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Tea Tour". The Tea Association of the USA. 11–17 August 2003. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ "Role of Tea in Development in Sri Lanka". United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008.

- ^ "South Asia Help for Sri Lanka's tea industry". BBC News. 4 April 1999. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ "Sri Lanka moves to protect tea industry". BBC News. 19 February 2003. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ "Just 64p a day for tea pickers in Sri Lanka". BBC News. 20 September 2005. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ a b c Holsinger, Monte (2002). "Thesis on the History of Ceylon Tea". History of Ceylon Tea. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ "Sri Lanka tops tea sales". BBC. 1 February 2002. Archived from the original on 2 May 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ "Merchandize exports reached US$ 13 Bn in 2022". Ada Derana. 31 January 2023. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ https://www.dailynews.lk/2025/01/29/business/712892/increase-in-lankan-tea-production-exports-and-national-average/

- ^ https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/Merchandise-exports-anchor-US---12-7bn-revenue-in-2024/108-301084

- ^ "Tea from Sri Lanka" (PDF). Sri Lanka Export Development Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Johnsson, S. (23 May 2016). "The green gold from Sri Lanka" (PDF). Linnaeus University. p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Ceylon Tea – The Official Overseas Sponsor of Sri Lanka Cricket". srilankateaboard.lk. Sri Lanka Tea Board. 7 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Who we are Archived 2017-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, Tea Research Institute – Sri Lanka. Retrieved April 2017

- ^ Löe, H, et al. Natural history of periodontal disease in humans. J Clin Perio 1986;13:431–440.

Further reading

[edit]- George Thornton Pett (1899). The Ceylon Tea-Makers' Handbook. The Times of Ceylon Steam Press, Colombo.

External links

[edit]- www

.pureceylontea .com, Official website of the Sri Lanka Tea Board - Taylor, Lipton and the Birth of Ceylon Tea

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch