Temple of Isis and Serapis

Temple of Isis and Serapis

The Temple of Isis and Serapis was a double temple in Rome dedicated to the Egyptian deities Isis and Serapis on the Campus Martius, directly to the east of the Saepta Julia. The temple to Isis, the Iseum Campense, stood across a plaza from the Serapeum dedicated to Serapis. The remains of the Temple of Serapis now lie under the church of Santo Stefano del Cacco, and the Temple of Isis lay north of it, just east of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.[1] Both temples were made up of a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic architectural styles.[2] Much of the artwork decorating the temples used motifs evoking Egypt, and they contained several genuinely Egyptian objects, such as couples of obelisks in red or pink granite from Syene.[3]

History

[edit]The cult was probably introduced in Rome during the 2nd century BC, as attested by two inscriptions discovered on the Capitoline Hill mentioning priests of Isis Capitolina.[4] Cassius Dio reports that in 53 BC the Senate ordered the destruction of all private shrines inside the pomerium dedicated to Egyptian gods;[5] however, a new temple to Serapis and Isis was voted by the second Triumvirate in 43 BC.[6] Repressive measures against Egyptian cults were decreed by Augustus in 28 BC,[7] Agrippa in 21 BC,[8] and Tiberius who, in 19 AD, had the priests of the goddess executed and the cult statue thrown into the Tiber.[9][10]

The cult was officially reinstalled sometime between the reign of Caligula and 65 AD,[11] and it continued to be practiced until the end of the late imperial period,[12][13] when all pagan cults were forbidden and Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire.

The precise date of the construction of the sanctuary in the Campus Martius is not known, but it has been suggested that it was built shortly after the Triumvirate's vote in 43 BC, between 20 and 10 BC,[14] or during the reign of Caligula (37-41 AD).[15] The whole complex was also rebuilt by Domitian after its destruction in the great fire of 80,[16][17] and later restored by Severus Alexander.[18] If still in use during the 4th-century, it would have been closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire.

A fire in the 5th century AD left the structure dilapidated,[19] and its last remains were probably destroyed in the following centuries,[14] although parts of it (such as the two entrance arches) might have survived until the Middle Ages.[20]

Placement and architecture

[edit]

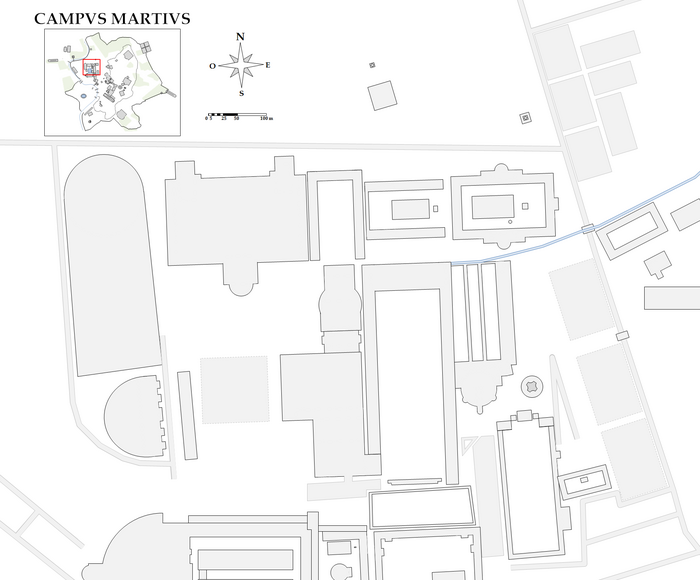

Juvenal[21] mentions the temple being standing next to the Saepta Iulia, a placement confirmed by the depiction on the Forma Urbis Romae showing a southern part comprising a semicircular apse with several exedrae, and a courtyard surrounded by porticoes on the north and southern sides, with an entrance to the East.[22]

It is difficult to gather more precise data about the original aspect of the sanctuary, as its architecture has been completely erased by later buildings and modifications to the area. The generally accepted reconstruction proposes that the whole area was a rectangle measuring about 220 x 70 m[23][24] that comprised wells, obelisks, and Egyptian statues, along with a small temple of Isis in the northern section.[25][26]

Depictions

[edit]The only known depictions of the sanctuary apart from the plan on the Forma Urbis are four denarii minted during the reigns of Vespasian and Domitian.[27] The earliest coin shows a small Corinthian temple on podium, with an Egyptian-style architrave with solar disk and ureai topped by a pediment showing Isis-Sothis riding the dog Sirius; the columns frame the cult statue of the goddess inside the cella.[28] The temple appears slightly different in a later emission, in which it has a flat roof, but the presence of the identical cult statue allows the identification with the same temple. Another coin shows a tetrastyle temple on podium with flat top, and a similar structure with a pediment, interpreted as the temple of Serapis. The last denarius depicts a three-bayed arch that could be the propylon to the sanctuary.[27] A similar arch with the inscription ARCVS AD ISIS is present in one of the reliefs from the 2nd-century AD Mausoleum of the Haterii. This structure has been identified with the Arco di Carmigliano, once standing across Via Labicana and dismantled in 1595, which would have constituted the eastern entrance to the sanctuary built by Vespasian.[14][29][30][31][32] It has also been proposed that the area could be accessed from the West through a quadrifrons arch built by Hadrian,[33] now part of the apse of the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva.[34][35]

Archaeological finds

[edit]

Many Egyptianizing sculptures, architectural fragments, and other objects, probably from the sanctuary, have been discovered in the area.[36] Among them are four pairs of obelisks:[37] the Pantheon Obelisk, the one in Villa Celimontana, the obelisk in Piazza della Minerva, the one on the Monument to the Battle of Dogali, and the one on the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona; one obelisk lies buried near the church of San Luigi dei Francesi; lastly, two more were brought outside Rome after antiquity: one is in Boboli Gardens (Florence), and one in Urbino. Other artifacts include Madama Lucrezia, considered by some scholars part of the decoration of the sanctuary or of the pediment of the temple of Isis;[38][39] the marble foot that is the namesake of Via del Piè di Marmo; four granite columns with reliefs representing Egyptian priests;[40] several Egyptian-style lotus-shaped capitals;[41] the Vatican Museum Pinecone; the statue of the Nile in the Vatican Museums, and the statue of the Tiber river with Romulus and Remus; a statue of Thoth as a baboon; and possibly the statues of lions now decorating the Fontana dell'Acqua Felice and the staircase leading to Piazza del Campidoglio and the statue of a cat in the adjacent Via della Gatta, along with the Bembine Tablet.

Cult statues

[edit]

It has been suggested that the cult statue of Isis might have been similar to the one currently in the Capitoline Museums based on the depictions of the statue found on coins.[42]

Other possible remains of a cult statue from the sanctuary are a head of Serapis in the Capitoline Museums and a statue of Cerberus in Villa Albani.[43]

Plan of the central Campus Martius

[edit]| Plan of the central Campus Martius |

|---|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Turcan, Robert. The Cults of the Roman Empire. Wiley, 1996. p. 106

- ^ Lollio Barberi, Parola, and Toti, Le antichità egiziane di Roma imperiale, p. 60.

- ^ Donalson, Malcolm Drew. The Cult of Isis in the Roman Empire: Isis Invicta. The Edwin Mellen Press, 2003. pp. 93, 96–102

- ^ CIL VI, 2247, 2248.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 40, 47

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 47, 15

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 53, 2

- ^ id., 54, 6

- ^ Tacitus, Annales 2, 85

- ^ Suetonius, Tiberius 36

- ^ Lucan, Pharsalia 8, 831

- ^ Takacs, Isis and Sarapis, p. 129

- ^ Ensoli and La Rocca, Aurea Roma, p. 279.

- ^ a b c Versluys, Aegyptiaca Romana, p. 354

- ^ A. Roullet, The Egyptian and Egyptianizing Monuments of Imperial Rome, Leiden 1972, p. 23.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 66, 24

- ^ Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita 7, 23

- ^ Historia Augusta, Alexander 26, 8

- ^ Versluys, "The Sanctuary of Isis on the Campus Martius in Rome", p. 164.

- ^ Ensoli, and La Rocca, Aurea Roma, p. 282.

- ^ Juvenal, Satires 6, 527 f.

- ^ "Stanford's Forma Urbis Romae Project". formaurbis.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-04-15.

- ^ Lembke, Das Iseum Campense in Rom.

- ^ Lollio Barberi, Parola and Toti, Le antichità egiziane di Roma imperiale, p. 59.

- ^ Lollio Barberi, Parola and Toti, Le antichità egiziane di Roma imperiale, pp. 64-65.

- ^ A. Roullet, The Egyptian and Egyptianizing Monuments of Imperial Rome, Leiden 1972, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Ensoli, L'Iseo e Serapeo del Campo Marzio, pp. 411-13.

- ^ Lollio Barberi, Parola and Toti, Le antichità egiziane di Roma imperiale, p. 65.

- ^ Ensoli, L'Iseo e Serapeo nel Campo Marzio, p. 411-14

- ^ Castagnoli, "Gli edifici rappresentati in un rilievo del sepolcro degli Haterii", p. 65

- ^ Platner, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, "Arcus ad Isis"

- ^ Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, p. 212

- ^ Versluys, "The Sanctuary of Isis on the Campus Martius in Rome", p. 160.

- ^ Ten, "Roma, il culto di Iside e Serapide in Campo Marzio", p. 274.

- ^ Takacs, Isis and Sarapis, p. 101.

- ^ A. Roullet, The Egyptian and Egyptianizing Monuments of Imperial Rome, Leiden, 1972, pp. 23–35

- ^ Platner, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, "Obeliscus Isei Campensis"

- ^ Ensoli and La Rocca, Aurea Roma, pp. 276-77.

- ^ Ensoli, L'Iseo e Serapeo del Campo Marzio, pp. 421-23.

- ^ H. Stuart Jones, ed., A Catalogue of the Ancient Sculptures Preserved in the Municipal Collections of Rome: The Sculptures of the Museo Capitolino Archived 2024-08-02 at the Wayback Machine (London 1912), p. 360, nos. 14, 15; A. Roullet, The Egyptian and Egyptianizing Monuments of Imperial Rome, Leiden 1972, pp. 57–58, nos. 16–19.

- ^ Ensoli, L'Iseo e Serapeo del Campo Marzio, p. 421.

- ^ Ensoli and La Rocca, Aurea Roma, p. 272.

- ^ Häuber and Schütz, "The Sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III in Rome", pp. 90-91.

Further reading

[edit]- Häuber, Chrystina and Franz Xaver Schütz. "The Sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III in Rome: Preliminary Reconstruction and Visualization of the ancient Landscape using 3/4D-GIS-Technology." Bollettino di Archeologia Online 2008 [1]

- Lembke, Katja. Das Iseum Campense in Rom : Studie über den Isiskult unter Domitian (in German). Verlag Archäologie und Geschichte, 1994.

- Lollio Barberi, Olga; Parola, Gabriele; Toti, Maria Pamela. Le antichità egiziane di Roma imperiale (in Italian). Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1995.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch