The Awful Truth

| The Awful Truth | |

|---|---|

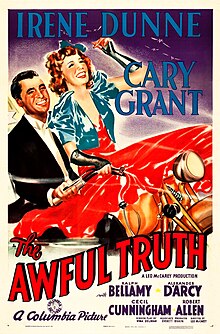

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Leo McCarey |

| Screenplay by | Viña Delmar |

| Based on | The Awful Truth 1922 play by Arthur Richman |

| Produced by | Leo McCarey |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph Walker |

| Edited by | Al Clark |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $600,000 ($12.7 million in 2023 dollars) |

| Box office | Over $3 million ($64 million in 2023 dollars) |

The Awful Truth is a 1937 American screwball comedy film directed by Leo McCarey, and starring Irene Dunne and Cary Grant. Based on the 1922 play The Awful Truth by Arthur Richman, the film recounts a distrustful rich couple who begin divorce proceedings, only to interfere with one another's romances.

This was McCarey's first film for Columbia Pictures, with the dialogue and comic elements largely improvised by the director and actors. Irene Dunne's costumes were designed by Robert Kalloch. Although Grant tried to leave the production due to McCarey's directorial style, The Awful Truth saw his emergence as an A-list star and proponent of on-the-set improvisation.

The film was a box office success and was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress (Dunne), and Best Supporting Actor (Ralph Bellamy), winning for Best Director (McCarey). The Awful Truth was selected in 1996 for preservation in the Library of Congress' National Film Registry, deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[1] The Awful Truth was the first of three films co-starring Grant and Dunne, followed by My Favorite Wife (1940) and Penny Serenade (1941).

Plot

[edit]Jerry Warriner tells his wife he is going on vacation to Florida, but instead spends the week at his sports club in New York City. He returns home to find that his wife, Lucy, spent the night in the company of her handsome music teacher, Armand Duvalle. Lucy claims his car broke down unexpectedly. Lucy discovers that Jerry did not actually go to Florida. Their mutual suspicion results in divorce proceedings, with Lucy winning custody of their dog. The judge orders the divorce finalized in 90 days.

Lucy moves into an apartment with her Aunt Patsy. Her neighbor is amiable but rustic Oklahoma oilman Dan Leeson, whose mother does not approve of Lucy. Jerry subtly ridicules Dan in front of Lucy, which causes Lucy to tie herself more closely to Dan. Jerry begins dating sweet-natured but simple singer Dixie Belle Lee, unaware that she performs an embarrassing, sexually suggestive act at a local nightclub.

Convinced that Lucy is still having an affair with Duvalle, Jerry bursts into Duvalle's apartment only to discover that Lucy is a legitimate vocal student of Duvalle and is giving her first recital. Realizing he may still love Lucy, Jerry undermines Lucy's character with Mrs. Leeson even as Dan and Lucy agree to marry. When Jerry attempts to reconcile with Lucy afterward, he discovers Duvalle hiding in Lucy's apartment and they have a fistfight while Dan and his mother apologize for assuming the worst about Lucy. When Jerry chases Armand out the door, Dan breaks off his engagement to Lucy and he and his mother return to Oklahoma.

A few weeks later, Jerry begins dating high-profile heiress Barbara Vance. Realizing she still loves Jerry, Lucy crashes a party at the Vance mansion the night the divorce decree is to become final. Pretending to be Jerry's sister, she undermines Jerry's character, implying that "their" father was working class rather than wealthy. Acting like a showgirl, she recreates Dixie's risqué musical number. The snobbish Vances are appalled.

Jerry attempts to explain away Lucy's behavior as drunkenness, and says he will drive Lucy home. Lucy repeatedly sabotages the car on the ride to delay their parting. Pulled over by motorcycle police officers, who believe Jerry is drunk, Lucy manages to wreck the car. The police give the couple a lift to Aunt Patsy's nearby cabin. Although sleeping in different (but adjoining) bedrooms, Jerry and Lucy slowly overcome their pride and a series of comic mishaps in order to admit "the awful truth" that they still love one another. They reconcile at midnight, just before their divorce is to be finalized.

Cast

[edit]The cast includes:[2]

- Irene Dunne as Lucy Warriner

- Cary Grant as Jerry Warriner

- Ralph Bellamy as Dan Leeson

- Alexander D'Arcy as Armand Duvalle

- Cecil Cunningham as Aunt Patsy

- Molly Lamont as Barbara Vance

- Esther Dale as Mrs. Leeson

- Joyce Compton as Dixie Belle Lee

- Robert Allen as Frank Randall

- Robert Warwick as Mr. Vance

- Mary Forbes as Mrs. Vance

- Zita Moulton as Lady Fabian (uncredited)

- Skippy as Mr. Smith, the dog (uncredited)

Pre-production

[edit]

The film is based on the stage play The Awful Truth by playwright Arthur Richman.[3][4] In that play, created on September 18, 1922, at the Henry Miller's Theater of Broadway (current Stephen Sondheim Theatre), Norman Satterly divorces his wife, Lucy Warriner Satterly, after they accuse one another of infidelity. Lucy is about to remarry, but needs to clear her name before her fiancé will agree to go forward with the marriage. As she tries to salvage her reputation, she falls in love again with her ex-husband and they remarry.[5]

There were two previous film versions, a 1925 silent film The Awful Truth from Producers Distributing Corporation[6] starring Warner Baxter and Agnes Ayres[7] and a 1929 sound version from Pathé Exchange,[7] The Awful Truth, starring Ina Claire and Henry Daniell.[8] Producer D.A. Doran had purchased the rights to the play for Pathé. When Pathé closed, he joined Columbia Pictures.[7] Columbia subsequently purchased all of Pathé's scripts and screenplay rights[7][9] for $35,000 ($800,000 in 2023 dollars).[10] Doran chose to remake the film in 1937, just as Columbia head Harry Cohn was hiring director Leo McCarey to direct comedies for the studio.[7][a]

Cohn offered the film to director Tay Garnett.[15] Garnett read Dwight Taylor's script, and felt it was "about as funny as the seven-year-itch in an iron lung."[16] He turned it down.[15] According to Garnett, McCarey accepted the project simply because he needed work. "Sure, the script was terrible, but I've seen worse. I worked it over for a few weeks, changed this and that. I finally decided I could make something of it."[16]

McCarey did not like the narrative structure of the play, the previous film versions,[9] or the unproduced Pathé script.[14] Cohn had already assigned Everett Riskin to produce the film,[10] and screenwriter Dwight Taylor had a draft script.[10][17] Taylor changed Norman Satterly to Jerry Warriner, got rid of much of the play's moralistic tone, and added a good deal of screwball comedy. Jerry is violence-prone (he punches Lucy in the eye), and the couple fight over a necklace (not a dog). Much of the action in Taylor's script is set at Jerry's club. The mishaps in the script cause Jerry to crack up emotionally. When the couple visit their old home (which is being sold at auction), his love for his wife is rekindled.[18]

McCarey didn't like Taylor's script.[19] He believed, however, that The Awful Truth would do well at the box office. With the Great Depression in its seventh year, he felt audiences would enjoy seeing a picture about rich people having troubles.[9] During face-to-face negotiations with Cohn, McCarey demanded $100,000 ($2.1 million in 2023 dollars) to direct. Cohn balked. McCarey wandered over to a piano and began to play show-tunes. Cohn, an avid fan of musicals, decided that anyone who liked that kind of music had to be talented—and he agreed to pay McCarey's fee.[20] He also agreed not to interfere in the production.[21]

McCarey's hiring was not announced until April 6, 1937.[11] Riskin withdrew from the film as McCarey insisted on producing.[19]

Script

[edit]McCarey worked with screenwriter Viña Delmar and her regular collaborator, her husband, Eugene.[22] The couple had written racy novels[23] as well as the source material and screenplay for McCarey's Make Way for Tomorrow.[24] The Delmars refused to work anywhere but their home, visit the studio or the set, or to meet any of the actors when working on a script.[22] In a letter to author Elizabeth Kendall, Viña Delmar said that McCarey worked with them on the script at their home, suggesting scenes.[22] McCarey asked the Delmars to drop the major plot points of the play—which focused on Dan Leeson's attempt to purchase mineral rights, a fire in Lucy Warriner's apartment building, and Lucy's midnight meeting with another man at a luxurious mountain resort—and focus on the pride which Jerry and Lucy feel and which keeps them from reconciling.[7]

According to the Delmars, they completed a script[25][b] which included musical numbers, making it resemble musical theatre more than screwball comedy.[27] It also largely retained the play's narrative structure, with four acts: the break-up at the Warriner house, events at Jerry Warriner's sports club, arguments and misunderstandings at Lucy Warriner's apartment, and a finale at Dan Leeson's apartment. The sets were simple, and few actors were needed.[9]

According to other accounts, Mary C. McCall Jr., Dwight Taylor (again), and Dorothy Parker all worked on the script as well.[28][29][c] None of their work was used by McCarey,[28] and Taylor even asked that his name be taken off the script.[30] Ralph Bellamy says that McCarey himself then wrote a script, completely reworking Delmar's effort.[28] Harry Cohn was not happy with McCarey's decision to abandon Delmar's work, but McCarey convinced the studio boss that he could rework it.[9] Film historians Iwan W. Morgan and Philip Davies say that McCarey retained only a single aspect of Delmar's work: The alleged infidelity of both man and wife.[25][d]

Casting

[edit]Irene Dunne had freelanced and had not been under contract to a studio since her arrival in Hollywood.[31] She appeared in Theodora Goes Wild (1936) for Columbia, and despite her misgivings about doing comedy her performance had garnered her an Academy Award nomination as Best Actress.[32] Dunne wanted to undertake a new project quickly after negative reaction to her performing in blackface in Show Boat (also 1936).[33][e] Her agent, Charles K. Feldman, helped develop The Awful Truth for Dunne,[37][38] and the film was rushed into production to accommodate her.[19][39] McCarey wanted her for the film[40] because he thought the "incongruity" of a "genteel" actress like Dunne in screwball comedy was funny,[41] and she was asked to appear in it even though Delmar was still working on a script.[7] Dunne was attached to the picture in mid-February 1937, although commitments to other stage and film projects meant production could not begin for several months.[36] Dunne was paid $75,000 ($1.6 million in 2023 dollars) for her work.[42][f] Dunne later said her decision to work on the film was "just an accident".[9]

Cary Grant was cast three days after Dunne.[46] Grant had also recently become a freelance actor without long-standing contractual obligations to any studio.[47] By late 1936, he was negotiating a contract with Columbia. He ran into McCarey on the street, and told McCarey he was free.[48] In February 1937, he signed a non-exclusive contract with Columbia Pictures in which he agreed to make four films over two years, provided each film was a prestige picture.[25] He was paid $50,000 ($1.1 million in 2023 dollars) to appear in The Awful Truth.[49][g] Grant was eager to work with McCarey,[25] McCarey wanted Grant,[40] and Cohn assigned Grant to the picture.[7]

For Ralph Bellamy, a contract player with Columbia, the film was just another assignment.[28] Delmar's draft script, sent to Bellamy by his agent,[29] originally described Dan Leeson as a conservative, prudish Englishman,[28] a role written with Roland Young in mind. Per his agent's request, Bellamy ignored the script. Some time later, Bellamy got a call from his good friend, the writer Mary McCall, who asked him to work with her on redeveloping the role. McCall had been instructed to change the Leeson character into someone from the American West. They spent an afternoon together, and recrafting the character as well as writing a scene for his entrance in the film.[29][h] After more time passed, Bellamy ran into writer Dwight Taylor at a cocktail party and learned that Taylor was rewriting his part. After a few weeks more, Dorothy Parker called Bellamy to tell him she was now working on the script and changing his role once more.[29] The second week of June 1937, Bellamy's agent told him he'd been cast in The Awful Truth and was to report to the studio the next Monday.[29] His casting was announced on June 23.[53]

Joyce Compton was cast on June 9,[54] and Alexander D'Arcy was cast some time before July 11.[55]

For the animal role of Mr. Smith, two dogs were cast but did not work out. Skippy, better known to the public as "Asta" in the Thin Man film series, was cast at the end of June. Skippy proved difficult to work with. For a critical scene in which Mr. Smith is to leap into Jerry Warriner's arms, a white rubber mouse (one of the dog's favorite toys) was placed in Cary Grant's breast pocket. But whenever Grant held his arms open, Skippy would dodge him at the last moment. It took several days to get the shot.[56] The human cast of The Awful Truth was also forced to take several unscheduled days of vacation in late July 1937 because Skippy was booked on another film.[57]

Pre-production activity

[edit]The Awful Truth was budgeted at $600,000 ($12.7 million in 2023 dollars).[58][i] Pre-production on the film neared completion at the beginning of May 1937.[60] Stephen Goosson was the supervising art director (his role today would be called production designer), and Lionel Banks the unit art director.[2] Goosson was a 20-year veteran art director for Columbia Pictures, and The Awful Truth is considered among his most important films of the 1930s.[61][j] Lionel Banks was primarily responsible for the production design of the film. He specialized in films set in the present day,[62] and created restrained, well-crafted[62] Art Deco sets for the picture.[63] The Awful Truth is considered one of his more elegant designs.[62][k]

Costumes

[edit]Columbia Pictures' chief costume and fashion designer, Robert Kalloch, created Dunne's wardrobe.[65] His work was personally approved by studio head Harry Cohn.[66] The clothes were the most elegant and expensive yet worn by her on film,[67][68] and costume design historian Jay Jorgensen has described them as "magnificent".[69] In 2012, Vanity Fair ranked The Awful Truth as one of the 25 most fashionable films ever made in Hollywood.[70]

Principal photography

[edit]Principal photography began on June 21, 1937,[71] without a completed script.[30][72][l] This so concerned Ralph Bellamy that the Friday before filming started he contacted Harry Cohn to ask where the script was. Cohn declined to say anything about the film, and allowed Bellamy to talk to Leo McCarey.[29] Bellamy went to McCarey's home to discuss the issue with him. McCarey was charming and witty, but evaded all of Bellamy's questions and concerns.[73]

Initial disruptiveness of McCarey's working style

[edit]The first four or five days on the set[73] were deeply upsetting to Dunne, Grant, and Bellamy due to the lack of a script and McCarey's working methods.[74] McCarey had the cast sit around on the set the first few days and largely swap stories.[28] The lack of rehearsal activity and script[m] caused Dunne such emotional distress that she spontaneously burst into tears several times each day.[75] Grant was so nervous that at times he became physically ill.[76] When McCarey bowed to the cast's concerns and blocked a scene for Dunne and Grant, Grant refused to perform it.[77]

Cary Grant in particular was unnerved by McCarey's behavior and lack of a script. Grant had spent most of his career at Paramount Studios, which had a factory-like approach to motion picture production;[78] actors were expected to learn their lines and be ready every morning, and shooting schedules were strictly enforced.[25] McCarey's improvisational style was deeply unsettling to Grant,[25] and at the end of the first week Grant sent Cohn an eight-page memorandum titled "What's Wrong With This Picture".[75] Grant asked Cohn to let him out of the film,[25][75][79] offering to do one or more pictures for free[28][75] and even saying he'd reimburse Cohn $5,000 if he were released.[75][80][n] McCarey was so angry at Grant that he stopped speaking to him and told Cohn he'd kick in another $5,000 to get Grant off the film.[17] Cohn ignored both the memo and the offers.[25][75] Grant also sought to switch roles with Bellamy[79][80] and asked Cohn to pressure McCarey into sticking to a more conventional style of filmmaking.[25] Again, Cohn said no to Grant's requests.[25][79] McCarey later said that Grant "had no sound judgment" when it came to determining what made for good comedy,[80] and McCarey seemed to harbor a grudge against Grant for decades for trying to get out of the picture.[30]

Cast support for improvisation

[edit]According to Bellamy, after the first five days, the three leads began to believe McCarey was a comedy genius.[73][77]

McCarey believed that improvisation was the key to great comedy.[25] "[A] lot of times we'd go into a scene [on The Awful Truth] with nothing at all", he said.[80] His working method was to ask his cast to improvise the scene,[25] creating their own dialogue and blocking their own action before allowing cameras to roll. If a problem arose with a scene, McCarey would sit at a piano on the set and pick out tunes and sing until a solution came to him.[80] McCarey supported his actors' comedy and other choices, which quickly alleviated the tension which had built up on the set.[75] For example, Ralph Bellamy was told to bring a selection of clothing from his own extensive, personal wardrobe.[81] He did so, but was worried that he had not been given costuming. McCarey told him that the clothes he'd brought from home fit the part perfectly, which made Bellamy feel comfortable in his acting and comedy choices.[75] McCarey was also extremely patient with his cast, understanding of their concerns, and sympathetic to their needs and problems. He also used his own wit to keep his cast in good humor.[73] Irene Dunne later recalled that the entire cast loved working on the picture because every day was full of laughter. Many actors didn't want each day's work to end, because they were having such a good time.[73]

Cary Grant began trusting the director[75] once he realized that McCarey recognized Grant's strengths[75] and welcomed Grant's ideas about blocking, dialogue, and comic bits.[82] McCarey also had the ability to get his performers to mimic his own unique mannerisms. (It was something Irene Dunne thoroughly admired.)[83] McCarey taught Grant a repertoire of comic vocalizations (like grunts) and movements and asked him to work with them. In turn, Grant imitated much of McCarey's own mannerisms and personality,[80] becoming a "clone" of McCarey.[28] Grant biographer Graham McCann says it would be an "overstatement" to say that McCarey gave Grant an on-screen personality.[82] Grant had been working on this acting persona for some time;[82][83] McCarey merely made Grant think more precisely about what he was trying to accomplish on camera.[82][o] Additionally, McCarey worked to give Grant comic dialogue and physical comedy (like pratfalls) as well as sophisticated dialogue and urbane moments, efforts which Grant also deeply appreciated.[80] Over time, Grant came to feel liberated rather than inhibited by the lack of a script, and seized the chance to make sure that the film's humor reflected his own. According to Ralph Bellamy, Grant enjoyed knowing that the audience was laughing at him, and worked to encourage it.[75] Grant also used his early feelings of frustration to build his character's emotional and sexual frustration in the film.[27][p]

Most of The Awful Truth was improvised on the set.[9] McCarey had two guides for directing the film. The first was that he believed the film was the "story of my life",[80] because McCarey based many scenes and comic moments on misunderstandings he had had with his own wife (although they never accused one another of infidelity).[83] The second guide was McCarey's own lengthy experience directing comedy. Jerry Warriner's need to find a lie to cover for his "boys' night out away from the wives" is a typical scenario McCarey used in many feature motion pictures and short films. It was also common in many of the Laurel and Hardy shorts which McCarey directed for only the man's alibi to break down. Subsequently, in The Awful Truth, it is Jerry's alibi that crumbles.[83] The bowler hat sequence in Lucy's apartment was based on a standard bit McCarey had frequently used in Laurel and Hardy films (as well as in the Marx Brothers' comedy Duck Soup (1933), which McCarey had also directed).[27] Dunne's increasingly outrageous mishaps with the car radio in the scene after Jerry and Lucy leave the Vance mansion is similar to Harpo Marx's misadventures with a radio in Duck Soup[84] and incorporates the straight man (Grant for Oliver Hardy) from Laurel and Hardy bits.[85]

McCarey also relied on his ability to craft a narrative from a series of unrelated sketches,[86][q] and he often staged portions of his films like musicals, inserting a song to tie elements together.[27]

Improvising the film

[edit]Irene Dunne had never met Cary Grant before, but she later recalled that they "just worked from the first moment" and called Grant a very generous actor.[9] Cary Grant, in turn, said "we just clicked". Dunne so trusted his comedy judgment that she would often turn to him after a take and ask in a whisper, "Funny?"[88]

Nearly every day during principal photography, Leo McCarey would arrive in the morning with ideas for the film written down on scraps of paper.[25][73][r] On days when he had nothing in mind, McCarey would arrive on the set and play the piano until inspiration struck. He would then have the script girl write down his ideas or dialogue, and give the actors their instructions.[30][s] Although he asked the cast to rehearse scenes, McCarey also encouraged his actors to improvise and build up the scene on their own. At times, McCarey himself acted out bits with the performers.[25][t] McCarey continued to meet with screenwriter Viña Delmar every evening,[90] sitting with her in a parked car on Hollywood Boulevard and improvising scenes for her to write down.[17][43] McCarey also relied for dialogue on writer Sidney Buchman, who had joined Columbia in 1934 and who had written Theodora Goes Wild for Irene Dunne.[91] Some of the best lines and comic moments in the film remained improvised, however.[26] For example, McCarey himself came up with the idea of arguing over a dog rather than property.[92] Another example occurs when Cary Grant appears at Lucy's apartment while she is meeting for the first time with Dan Leeson. The writers did not have a line of dialogue for Grant, who ad-libbed the line, "The judge says this is my day to see the dog."[76][93][94] Grant and Dunne also came up with the idea for Jerry to tickle Lucy with a pencil while Dan Leeson is at Lucy's door.[95] Grant quickly became an accomplished improvisational actor during the shoot. He ad-libbed with such speed and composure that his co-stars often "broke character".[93]

The nightclub scene was apparently also somewhat improvised on the set. In the Delmar script, Jerry's date is named Toots Biswanger and the scene is meant to parody the novel Gone with the Wind (two years before the film). She has a Southern American English accent, and Toots believes her song is a tribute to the novel. Jerry has a line in which he slyly criticizes Lucy's date by telling Dan "It's a book." As Toots sings the song's critical line ("my dreams are gone with the wind"), the wind machine on the stage was to have blown off her hat, then her muff, then her cape.[95] On the set, the singer's name is changed to Dixie Belle, much of the dialogue is improvised, and the wind machine joke changed to a more restrained blowing of the dress.[96]

According to Dunne, the action and dialogue for the scene in the Vance mansion was all written on the set.[89] Dunne choreographed the dance and at least one line of dialogue,[97] while the bit with the long handkerchief was a classic comic routine from silent films.[98]

Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn was not happy with McCarey's directorial methods, either. On the first day of shooting,[28][44] he walked onto the soundstage to see Bellamy singing Home on the Range off-key while Dunne tried to pick out the tune on a piano. He shook his head in disbelief and left.[9] Later, Cohn became angry when he learned McCarey was apparently dawdling on the set by playing the piano and telling stories. He angrily confronted McCarey in front of the cast and crew, shouting, "I hired you to make a great comedy so I could show up Frank Capra. The only one who's going to laugh at this picture is Capra!"[40] When Cohn caught McCarey playing the piano another time, McCarey dismissed his concerns by claiming to be writing a song for the film.[44] Cohn also came on the set the day Harold Lloyd was visiting. Cohn was so incensed that McCarey seemed to be telling jokes that he ordered the set cleared. Lloyd departed, and so did McCarey. Cohn finally reached McCarey at home, and in a profanity-laced conversation demanded that McCarey return to work. McCarey demanded in turn that Cohn apologize personally to everyone on the set, and send his apology to Lloyd. Cohn, unwilling to abandon the picture, perfunctorily apologized.[14] Nevertheless, Cohn did not rein in the director.[25] Cohn decided instead to write the entire picture off as a loss, since he was obligated to pay Dunne's salary whether the film was made or not and he could not fire McCarey since only McCarey knew where the film was headed.[43]

Improvisation proved to be a problem for actor Alexander D'Arcy, who played the suave musician Armand Duvalle. Initially, D'Arcy portrayed Duvalle as French. Columbia Pictures' in-house censors vetoed his performance, saying it would offend overseas audiences. D'Arcy tried an Austrian, Italian, Spanish, and even vaguely South American persona. Each time, the censors disapproved of his work. Finally, after much experimentation, the actor's makeup was changed to fair from swarthy, he was told not to gesticulate too much, and he created a nondescript, vaguely European accent (which was nicknamed "Spenchard") for his role.[99] The accent proved difficult to maintain. During long takes, D'Arcy would slip into his native French-inflected voice, forcing these scenes to be reshot multiple times.[55]

Improvisation could sometimes be a risky choice for the production in other ways as well. Delmar's script called for the film to be set in Connecticut. The critical plot element had the divorce court judge issue a 90-day interlocutory decree, and it is during this period in which most of the action in the film occurs. As filming commenced, it became clear that no one knew if Connecticut permitted interlocutory decrees. It turned out that the state did not, and Columbia Pictures' in-house lawyers could not determine which state did. By coincidence, David T. Wilentz, the New Jersey Attorney General, was visiting Los Angeles. McCarey called him on the telephone, and Wilentz confirmed that New Jersey divorce courts used them. The setting of the film was then changed to New Jersey.[100] Improvisation also led to minor visual inconsistencies in the film, such as when Jerry Warriner appears to both stand and sit during the divorce proceedings.[27]

Songs and choreography

[edit]During pre-production, McCarey knew that he needed two songs for important scenes in the picture.[27] Composer Ben Oakland and lyricist Milton Drake wrote two numbers for the film, "I Don't Like Music" and "My Dreams Are Gone with the Wind".[101] Both were finished by the time principal photography began.[102] Compton's original delivery of "My Dreams Are Gone with the Wind" and Dunne's reprise of it were filmed by July 25.[103]

One critical scene in The Awful Truth occurs in a nightclub, during which both Dunne and Grant dance. In a second scene, Dunne's character dances in front of Jerry, his fiancée, and her family. Usually, the production would hire a choreographer for these scenes, but McCarey declined to do so. Instead, he asked an African American youth working on the Columbia lot to teach Dunne and Grant how to dance. Their inept efforts to imitate him made their on-screen dances funnier.[104] Ralph Bellamy was required to do the fictional "Balboa Stomp" in the nightclub scene while Irene Dunne largely stands by, feebly trying to imitate him. The dance proved so physically intimidating that Bellamy lost 15 pounds (6.8 kg)[105] and his muscles and joints were sore for weeks afterward.[106] Irene Dunne choreographed the burlesque dance which her character performs at the Vance mansion to embarrass Jerry. In rehearsal, Leo McCarey asked her to insert a "stripper bump"[u] into her routine. Dunne replied, "Never could do that." McCarey laughed so hard at her response that he asked her to include it in the performance.[97]

One of the film's best remembered comedy moments is when Lucy Warriner accompanies an out of tune Dan Leeson on the piano while he sings "Home on the Range". This was filmed on June 21, the first day of filming.[28][107] McCarey wanted the song in the film, but knew neither performer would agree if requested. Instead, McCarey tricked them into it[75] by casually asking Dunne if she could play the piano. She said she could, a little.[43][107] McCarey then asked Bellamy if he could sing. The actor said he knew the words to the song, but could not sing.[28] McCarey asked them to do the song anyway, telling Bellamy to "belt it out" in an Oklahoman accent.[75][v] McCarey had their performance filmed,[43][107] and it turned out so well that he ordered the footage printed.[28] Dunne was furious when she realized McCarey had intended to use the footage in the film all along.[107]

Cinematography and editing

[edit]Cinematographer Joseph Walker[27] used mainly long takes when shooting The Awful Truth. With McCarey providing only minimal direction, this helped to make scenes feel spontaneous and energetic. Generally, a scene would only be shot once unless there was a mistake,[43][98] and shooting days were kept short[43] (often ending at 3 PM).[14][w] One particular scene, however, took nearly a full day to film. During the film's finale, shot about August 10,[109] Delmar's script called for a cat to block the door connecting Jerry and Lucy's bedrooms, impeding Jerry's attempt at a marital reconciliation. An animal wrangler brought five cats in the morning, but none would stand still. Frustrated, McCarey called another animal wrangler, who soon arrived with three more cats. None would stay still. Three more animal wranglers were called during the day, but none of the cats would perform as required.[110][x] Finally, McCarey was forced to issue an open call to the public for anyone with a cat who would perform the actions required. When a cat was found that would stay still, the animal refused to move when Cary Grant attempted to open the door.[109]

The Awful Truth was shot primarily on a soundstage at Columbia Pictures' Gower Street studios. Principal photography ended on August 17, 1937,[71] the 37th day of shooting.[14][y] At end of August, location shooting occurred at Columbia Ranch, the studio's 40-acre (16 ha) lot located at the corner of Hollywood Way and Oak Street in Burbank, California.[111] Reshoots on the film occurred during the first week of October.[112]

McCarey did not permit Joseph Walker to shoot much coverage, preferring to "edit in the camera". This left editor Al Clark with few choices once the film began to be pieced together.[113] One major cut made to the film was actor Claud Allister's performance as Lord Fabian in the Vance drawing room scene, which was completely excised.[114] Film historian James Harvey says that the comic timing of Clark's editing in the nightclub scene—cutting from Dixie Belle Lee's performance to Jerry, Lucy, and Dan at the table—is "exquisite...unmatched deadpan brilliance".[115]

Previews and release

[edit]The Awful Truth was shot in just six weeks,[73][116] a record for a film of this genre (according to Ralph Bellamy).[73] It was finished ahead of schedule and $200,000 ($4.2 million in 2023 dollars) under budget.[43] The film contained several risqué moments which normally would have run afoul of the Motion Picture Production Code, including Jerry making double entendres about coal mines to an oblivious Dan, Dixie Belle Lee's exposed underwear, Lucy "goosing" pompous Mrs. Vance, and the final moment of the film when the cuckoo clock figures go into the same room together. Code administrator Joseph Breen permitted these gags because the picture and its cast were high-quality, which served to undercut the raciness of the moments.[117]

The film was test screened, and the audience's reaction was good but not outstanding.[118] Audiences were unused to seeing the three stars in a comedy, and were unsure whether they should laugh.[108] McCarey realized the opening was too somber, and that viewers were not certain the picture was a comedy. He rewrote the opening scenes,[118] adding one in which Lucy calls her attorney to discuss her impending divorce. A new bit in this scene helped establish the tone of the film more clearly. While on the phone, Lucy's lawyer tries to tell her that "Marriage is a beautiful thing". Each time, his wife (standing in the background of the shot) yells impatiently at him to remind him that dinner is ready. This happens three times. The attorney's response is harsher the second time. The third time, he shouts back "Shut your big mouth!"[119] At a second preview, audiences roared with laughter.[108]

The Awful Truth was released in theaters in the United States on October 21, 1937.[71]

Box office and reception

[edit]Gross box office receipts for The Awful Truth were more than $3 million ($64 million in 2023 dollars).[120] The film made a profit of $500,000 ($10.6 million in 2023 dollars) in a year when Columbia Pictures' studio-wide profit margin was just $1.3 million ($27.6 million in 2023 dollars).[93]

The Film Daily named The Awful Truth as one of the ten best films of 1937.[121]

Although he was not nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor, the film was a triumph for Cary Grant. Overnight he was transformed into an A-list leading man.[80] "The Cary Grant Persona"[122] was fully established by this film, and Grant not only became an able improviser but often demanded improvisation in his films thereafter.[82] Ralph Bellamy, however, was typecast for years in "amiable dope" roles after The Awful Truth.[27]

Awards and honors

[edit]The film was nominated for six Academy Awards (only winning Best Director for Leo McCarey).[76][93][123][z]

After winning the Oscar, McCarey said he had won it for the wrong picture, since he considered his direction of the 1937 melodrama Make Way for Tomorrow to be superior.[125]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Outstanding Production | Leo McCarey and Everett Riskin (for Columbia) | Nominated |

| Best Director | Leo McCarey | Won | |

| Best Actress | Irene Dunne | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ralph Bellamy | Nominated | |

| Best Adaptation | Viña Delmar | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Al Clark | Nominated | |

| National Film Preservation Board | National Film Registry | The Awful Truth | Inducted |

The Awful Truth was selected in 1996 for preservation in the Library of Congress' National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[126]

The film has since been recognized twice by American Film Institute:

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – No. 68[127]

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – No. 77[128]

Subsequent versions

[edit]Dunne, Grant, and Bellamy performed scenes from The Awful Truth on the Hollywood Hotel radio program on CBS on October 15, 1937.[129]

The Awful Truth was presented as a one-hour radio program on three occasions on Lux Radio Theatre. On the September 11, 1939 broadcast Grant and Claudette Colbert starred in the adaptation.[130] Bob Hope and Constance Bennett played the leads for the March 10, 1941 version.[131] Dunne and Grant reprised their original lead roles on the January 18, 1955, broadcast.[129]

Dunne reprised her Lucy Warriner role in a 30-minute version of The Awful Truth on The Goodyear Program on CBS on February 6, 1944. Walter Pidgeon played the role of Jerry Warriner.[129]

The play inspired a film musical, Let's Do It Again (1953), starring Jane Wyman and Ray Milland.[2]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Although a number of sources claim McCarey was on loan from Paramount Pictures,[11][12][13] the director had been fired from Paramount due to the poor box office performance of his film Make Way for Tomorrow. Cohn did not hire McCarey until after McCarey left Paramount.[14]

- ^ Columbia Pictures archives show it was finished on June 15, six days before shooting was to begin.[26]

- ^ Author Elizabeth Kendall says Parker worked on the script with her husband, Alan Campbell.[22] Bellamy says that it was Harry Cohn who assigned the script to Parker and her husband.[29] According to Ralph Bellamy, these scripts were worked on during the several months before shooting began,[29] although the timeline is not clear.

- ^ The play and the two previous film versions had focused only on the wife's infidelity.[25]

- ^ Film historian Wes Gehring claims Dunne wanted to do a comedy to restore her public appeal and prestige after the box office failure of High, Wide and Handsome.[34] This seems unlikely, as that film did not premiere until July 21, 1937,[35] and Dunne had signed on to The Awful Truth five months earlier.[36]

- ^ In 1935, Dunne signed a three-picture deal with Columbia Pictures, guaranteeing her $65,000 for her first film, $75,000 for her second, and $85,000 for her third.[42] She was to be paid whether the film she was assigned to was made or not.[43][44] Her total income for 1937 was $259,587 ($5.5 million in 2023 dollars).[45]

- ^ Grant's contract paid the actor $50,000 for each of the first two movies, and $75,000 for each for the third and fourth films.[49] The first two films were When You're in Love (released February 16, 1937)[50] and The Awful Truth (released October 21, 1937). The second two films were Holiday (released June 15, 1938)[51] and Only Angels Have Wings (released May 15, 1939).[52] Grant's total income for 1937 was $144,291 ($3.1 million in 2023 dollars).[45]

- ^ Leeson was to have climbed down a fire escape at a hotel and entered Lucy's room through a window.[29]

- ^ Columbia made three kinds of pictures in the 1930s and 1940s: "AA", which cost about $1 million each; "Nervous A", which cost about $500,000 to $750,000; and "B" or "programmers", budgeted at $250,000. "Nervous A" films had lower budgets than "AA" films, but were expected to perform about the same at the box office. Savings in any single category could be applied to the budgets of other films, which often meant that a "Nervous A" or "B" picture could cost more than its average budget.[58] About 70 percent of Columbia's films in the 1930s and 1940s were "B" movies, but the "AA" and "Nervous A" films produced 60 percent of the studio's profit.[59]

- ^ The others are American Madness, You Can't Take It With You, It Happened One Night, and Lost Horizon.[61]

- ^ Banks had worked on a single film for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1935 before joining Columbia Pictures in 1937. He would be nominated for an Academy Award for his art direction on Holiday in 1938.[64]

- ^ Kendall says there was a completed script,[26] but all other sources disagree. It may be that the completed script was not given to the cast.

- ^ One source says Dunne had seen fragments of a script.[14]

- ^ Grant allegedly asked his friend, actor Joel McCrea, to take over the part.[30]

- ^ McCarey appeared to hold a grudge against Grant for the rest of his life. Peter Bogdanovich believes McCarey felt "Grant never gave him enough credit for basically handing him the characteristics he would play variations on throughout the rest of his career". Grant never seemed upset by McCarey's ill-will, apparently understanding why McCarey felt the way he did.[80]

- ^ Irene Dunne says she helped "calm down" Grant's deep unease over the lack of a script.[72]

- ^ McCarey called this narrative the "ineluctability of incidents".[87]

- ^ According to Cohn biographer Bob Thomas, McCarey often wrote down dialogue and directions for the day while riding in a taxi from his home to the studio.[44]

- ^ Dunne told an interviewer that all the film's dialogue was written by McCarey on the set, while the crew and actors waited.[89]

- ^ According to sound supervisor Edward Bernds, improvisation almost always occurred during rehearsal. Lines might be improvised while photography occurred, but blocking never was. The microphone operator had to know where the boom went in order to capture the sound.[90]

- ^ This is a physical move where the performer swiftly pushes the hips forward suddenly, as if thrusting sexually. It is often performed with the hands behind the head or on the hips. In live theater, especially vaudeville, it might be accompanied by a rimshot or cymbal strike for comic effect.

- ^ At this point, Bellamy did not know what part he was to play, or that Dan Leeson was to be from Oklahoma.[81]

- ^ In one case, McCarey shot a close-up of Dunne and Grant three times when he felt that their expressions did not communicate enough love for one another.[108]

- ^ Two of the cats escaped their handlers and sought refuge in the catwalks above the soundstage. Three got beneath the stage itself, and began yeowling.[110]

- ^ Cohn, visiting the set that day, was apoplectic to see McCarey serving the cast and crew drinks. His anger subsided when McCarey told him they'd just wrapped.[14]

- ^ Although remembered today for its set design, The Awful Truth was not nominated for its production design in 1937. Goosson was nominated and won for art direction for Lost Horizon,[124] which was released on February 17, 1937.[51]

References

[edit]- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Eagan 2010, p. 264.

- ^ Leonard 1981, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Sloan, J. Vandervoort (March 1923). "The Loop Faces South". The Drama. p. 215. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Kendall 2002, p. 195.

- ^ Katchmer 1991, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eagan 2010, p. 265.

- ^ Vermilye 1982, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bawden & Miller 2017, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1990, p. 122.

- ^ a b Parsons, Louella O. (April 7, 1937). "McCarey Is Named to Direct Irene Dunne in 'Awful Truth'". San Francisco Examiner. p. 19.

- ^ "McCarey Plans Stage Drama". Los Angeles Times. April 10, 1937. p. 23

- ^ "Developing of Screen Stories Found Expensive". Los Angeles Times. July 28, 1937. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thomas 1990, p. 125.

- ^ a b Schultz 1991, p. 89.

- ^ a b Garnett & Balling 1973, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Wansell 1983, p. 121.

- ^ Kendall 2002, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1990, p. 123.

- ^ Greene 2008, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Kendall 2002, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d Kendall 2002, p. 196.

- ^ Welch 2018, pp. 776–777.

- ^ Nelmes & Selbo 2018, pp. 776–777.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Morgan & Davies 2016, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Kendall 2002, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eagan 2010, p. 266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bawden & Miller 2017, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Maltin 2018, p. 171.

- ^ a b c d e Harvey 1998, p. 269.

- ^ Carman 2016, pp. 48–52.

- ^ Gehring 2006, p. 38.

- ^ Devine, John F. (April 1937). "Irene Goes Wild". Modern Movies. pp. 34–35, 73–75.

- ^ Gehring 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Schultz 1991, p. 13.

- ^ a b Parsons, Louella O. (February 16, 1937). "Columbia Buys Comedy Success for Irene Dunne". San Francisco Examiner. p. 23.

- ^ Carman 2016, pp. 24, 173 fn. 58.

- ^ Kemper 2010, p. 90.

- ^ Schultz 1991, p. 276.

- ^ a b c Wiley, Bona & MacColl 1986, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Parish 1974, p. 154.

- ^ a b Dick 2009, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Greene 2008, p. 266.

- ^ a b c d Thomas 1990, p. 124.

- ^ a b "Film Industry Leads High-Salaried Field". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. April 8, 1939. p. 5.

- ^ "Bits From the Studios". The Pittsburgh Press. February 19, 1937. p. 24.

- ^ McCann 1998, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Wansell 1983, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Morecambe & Sterling 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Larkin 1975, p. 212.

- ^ a b Larkin 1975, p. 116.

- ^ Larkin 1975, p. 271.

- ^ Parsons, Louella O. (June 24, 1937). "Carl Laemmle, Jr., Plans More Eerie Melodrama". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 12.

- ^ "The Movie Lots Beg to Report". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 10, 1937. p. 19.

- ^ a b Parsons, Louella O. (July 11, 1937). "Movie-Go-Round". San Francisco Examiner. p. 27.

- ^ Carroll, Harrison (July 2, 1937). "Movie Gale Batters Actors". Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph. p. 12.

- ^ Megahan, Urie (July 29, 1937). "'Stargazing' With Urie Megahan". Indiana Weekly Messenger. p. Town Weekly Magazine Section 11.

- ^ a b Dick 2009, p. 120.

- ^ Bohn & Stromgren 1987, p. 212.

- ^ Percy, Eileen (May 1, 1937). "Half Dozen Pictures Get Going at Columbia Studio". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 9.

- ^ a b Stephens 2008, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Stephens 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Ramirez 2004, p. 189.

- ^ Stephens 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Graham, Sheilah (July 26, 1937). "Dressy Afternoon Costume Designed". The Indianapolis Star. p. 4.

- ^ Thomas 1990, p. 73.

- ^ Day, Sara (August 15, 1937). "Fashioned for Luxury". Detroit Free Press. p. Screen & Radio Weekly 11.

- ^ "Film Fashions". Bathurst National Advocate. November 26, 1937. p. 8. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Jorgensen 2010, p. 77.

- ^ Jacobs, Laura (September 2012). "Scenes of Glamour". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Awful Truth, The (1937)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Gehring 2002, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gehring 2006, p. 86.

- ^ McCann 1998, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m McCann 1998, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Gehring 2006, p. 88.

- ^ a b McCann 1998, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Kendall 2002, pp. 197–198.

- ^ a b c Eagan 2010, pp. 265–266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bogdanovich 2005, p. 101.

- ^ a b Maltin 2018, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b c d e McCann 1998, p. 97.

- ^ a b c d Gehring 2006, p. 85.

- ^ Gehring 2007, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Gehring 2002, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Gehring 2006, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Daney, Serge; Noames, Jean-Louis (January 1967). "Taking Chances". Cahiers du Cinéma in English. p. 53.

- ^ Bawden & Miller 2017, p. 123.

- ^ a b Harvey 1998, p. 682.

- ^ a b Bernds 1999, p. 290.

- ^ Stempel 2000, p. 101.

- ^ Kendall 2002, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d McCann 1998, p. 88.

- ^ Wansell 1983, p. 122.

- ^ a b Kendall 2002, p. 203.

- ^ Kendall 2002, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b Gehring 2006, p. 9.

- ^ a b Harvey 1998, p. 683.

- ^ Shaffer, George (September 7, 1937). "Plays Villain of Five Lands, Then All in One". Chicago Tribune. p. 20.

- ^ "Hollywood Talkie-Talk". Baltimore Evening Sun. September 22, 1937. p. 23.

- ^ Burton 1953, p. 99.

- ^ Parsons, Louella O. (June 25, 1937). "Warners and Selznick Plan John D. Rockefeller Pictures". San Francisco Examiner. p. 16.

- ^ "On the Lots With the Candid Reporter". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. July 25, 1937. p. 60.

- ^ "Talk of the Talkies". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 6, 1937. p. 17.

- ^ Parsons, Louella O. (July 22, 1937). "Russell, Once 'Another Loy', Cast With Her". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 12.

- ^ Kendall, Read (September 9, 1937). "Around and About Hollywood". Los Angeles Times. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Maltin 2018, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1990, p. 126.

- ^ a b Harrison, Paul (August 12, 1937). "The Kitty May Be Incidental to the Film, But Never to Actors and the Director". La Crosse Tribune. p. 12.

- ^ a b Harrison, Paul (August 26, 1937). "The Kitty May Be Incidental to the Film, But Never to Actors and the Director". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 16.

- ^ Fidler, Jimmie (August 26, 1937). "Makes Good By Making Good Films". South Bend Tribune. p. 15.

- ^ Fidler, Jimmie (October 7, 1937). "Says Women Have Future in Hollywood". South Bend Tribune. p. 16.

- ^ Gehring 1986, p. 90.

- ^ Harvey 1998, p. 222.

- ^ Harvey 1998, p. 237.

- ^ Pallot 1995, p. 42.

- ^ Leff & Simmons 2001, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Gehring 2006, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Gehring 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (December 26, 1937). "Hollywood Sets Cap for Bigger Film Grosses". Los Angeles Times. p. C1.

- ^ "The Ten Best Pictures of 1937". The Film Daily. January 6, 1938. pp. 9–24. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Morecambe & Sterling 2001, p. 232.

- ^ Eliot 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Pickard 1979, p. 95.

- ^ Gold, Daniel M. (July 16, 2016). "With 'Seriously Funny,' MoMA Celebrates Leo McCarey, an Early Film Talent". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ D'Ooge, Craig (December 30, 1996). "Mrs. Robinson Finds A Home". Library of Congress Information Bulletin. pp. 450–451. hdl:2027/mdp.39015082978449. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Schultz 1991, p. 138.

- ^ "Those Were The Days". Nostalgia Digest. Summer 2015. pp. 32–39.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Radio Programs". The Pittsburgh Press. March 10, 1941. p. 16. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bawden, James; Miller, Ron (2017). Conversations with Classic Film Stars: Interviews From Hollywood's Golden Era. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813174389.

- Bernds, Edward (1999). Mr. Bernds Goes to Hollywood: My Early Life and Career in Sound Recording at Columbia With Frank Capra and Others. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810836020.

- Bogdanovich, Peter (2005). Who the Hell's In It: Conversations With Hollywood's Legendary Actors. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345480026.

- Bohn, Thomas W.; Stromgren, Richard L. (1987). Light and Shadows: A History of Motion Pictures. Palo Alto, Calif.: Mayfield Publishing Co. ISBN 9780874847024.

- Burton, Jack (1953). The Blue Book of Hollywood Musicals. New York: Century House. OCLC 59929221.

- Carman, Emily (2016). Independent Stardom: Freelance Women in the Hollywood Studio System. Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9781477307311.

- Dick, Bernard F. (2009). The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row: Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813193236.

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York: Continuum. ISBN 9780826418494.

- Eliot, Marc (2009) [1960]. Cary Grant: A Biography. London: Aurum. ISBN 9781845131517.

- Garnett, Tay; Balling, Fredda Dudley (1973). Light Your Torches and Pull Up Your Tights. New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington House. ISBN 9780870002045.

- Gehring, Wes D. (1986). Screwball Comedy: A Genre of Madcap Romance. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313246500.

- Gehring, Wes D. (2002). Romantic vs. Screwball Comedy: Charting the Difference. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810844247.

- Gehring, Wes D. (2006). Irene Dunne: First Lady of Hollywood. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810858640.

- Gehring, Wes D. (2007). Film Clowns of the Depression: Twelve Defining Comic Performances. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 9780786428922.

- Greene, Robert (2008). The 33 Strategies of War. London: Profile. ISBN 9781861979988.

- Harvey, James (1998). Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, From Lubitsch to Sturges. New York: Da Capo Pres. ISBN 9780306808326.

- Jorgensen, Jay (2010). Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood's Greatest Costume Designer. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 9780762438051.

- Katchmer, George A. (1991). Eighty Silent Film Stars: Biographies and Filmographies of the Obscure to the Well Known. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 9780899504940.

- Kemper, Tom (2010). Hidden Talent: The Emergence of Hollywood Agents. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520257061.

- Kendall, Elizabeth (2002). The Runaway Bride: Hollywood Romantic Comedy of the 1930s. New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 9780815411994.

- Krasna, Norman (1986). "Norman Krasna: The Woolworth's Touch". In McGilligan, Patrick (ed.). Backstory: Interviews With Screenwriters of Hollywood's Golden Age. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520056664.

- Larkin, Rochelle (1975). Hail, Columbia. New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington House. ISBN 9780870002397.

- Leff, Leonard J.; Simmons, Jerold L. (2001). The Dame in the Kimono: Hollywood, Censorship, and the Production Code. Lexington, Ky.: University of Kentucky Press. ISBN 9780813190112.

- Leonard, William T. (1981). Theatre: Stage to Screen to Television. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810813748.

- Maltin, Leonard (2018). Hooked on Hollywood: Discoveries From a Lifetime of Film Fandom. Pittsburgh: GoodKnight Books. ISBN 9780998376394.

- McCann, Graham (1998). Cary Grant: A Class Apart. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231109932.

- Morecambe, Gary; Sterling, Martin (2001). Cary Grant: In Name Only. London: Robson Books. ISBN 9781861054661.

- Morgan, Iwan W.; Davies, Philip (2016). Hollywood and the Great Depression: American Film, Politics and Society in the 1930s. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781474431927.

- Nelmes, Jill; Selbo, Jule (2018). Women Screenwriters: An International Guide. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9781349580866.

- Pallot, James (1995). The Movie Guide. New York: Berkley Publishing Group. ISBN 9780399519147.

- Parish, James Robert (1974). The RKO Gals. New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington House. ISBN 9780870002465.

- Pickard, Roy (1979). Hollywood Gold: The Award Winning Movies. New York: Taplinger Publishing Co. ISBN 9780800839192.

- Picken, Mary Brooks (1999). A Dictionary of Costume and Fashion: Historic and Modern. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486402949.

- Ramirez, Juan Antonia (2004). Architecture for the Screen: A Critical Study of Set Design in Hollywood's Golden Age. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 9780786417810.

- Schultz, Margie (1991). Irene Dunne: A Bio-Bibliography. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313273995.

- Stempel, Tom (2000). Framework: A History of Screenwriting in the American Film. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815606543.

- Stephens, Michael L. (2008). Art Directors in Cinema: A Worldwide Biographical Dictionary. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 9780786437719.

- Thomas, Bob (1990) [1967]. King Cohn: The Life and Times of Hollywood Mogul Harry Cohn. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070642614.

- Vermilye, Jerry (1982). Films of the Thirties. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press. ISBN 9780806508078.

- Wansell, Geoffrey (1983). Cary Grant: Haunted Idol. London: Collins. ISBN 9780002163712.

- Welch, Roseanne (2018). "Vina Delmar". Women Screenwriters: An International Guide. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781349580866.

- Wiley, Mason; Bona, Damien; MacColl, Gail (1986). Inside Oscar: The Unofficial History of the Academy Awards. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345314239.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch