List of fountains in Rome

This is a list of the notable fountains in Rome, Italy. Rome has fifty monumental fountains and hundreds of smaller fountains, over 2000 fountains in all, more than any other city in the world.[1][2]

History

[edit]For more than two thousand years fountains have provided drinking water and decorated the piazzas of Rome. During the Roman Empire, in 98 AD, according to Sextus Julius Frontinus, the Roman consul who was named curator aquarum or guardian of the water of the city, Rome had nine aqueducts which fed 39 monumental fountains and 591 public basins, not counting the water supplied to the Imperial household, baths and owners of private villas. Each of the major fountains was connected to two different aqueducts, in case one was shut down for service.[3]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the aqueducts were wrecked or fell into disrepair, and the fountains stopped working. In the 14th century, Pope Nicholas V (1397–1455), a scholar who commissioned hundreds of translations of ancient Greek classics into Latin, decided to embellish the city and make it a worthy capital of the Christian world. In 1453 he began to rebuild the Acqua Vergine, the ruined Roman aqueduct which had brought clean drinking water to the city from eight miles (13 km) away. He also decided to revive the Roman custom of marking the arrival point of an aqueduct with a mostra, a grand commemorative fountain. He commissioned the architect Leon Battista Alberti to build a wall fountain where the Trevi Fountain is now located. Alberti restored, modified, and expanded the aqueduct that supplied both the Trevi Fountain as well as the famous baroque fountains in the Piazza del Popolo and Piazza Navona.[4]

One of the first new fountains to be built in Rome during the Renaissance was the Fountain in Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere (1499), which was placed on the site of an earlier Roman fountain. Its design, based on an earlier Roman model, with a circular vasque on a pedestal pouring water into a basin below, became the model for many other fountains in Rome, and eventually for fountains in other cities, from Paris to London.[5]

During the 17th and 18th century the Roman popes reconstructed other ruined Roman aqueducts and built new display fountains to mark their termini, launching the golden age of the Roman fountain. The fountains of Rome, like the paintings of Rubens, were expressions of the new style of Baroque art. They were crowded with allegorical figures, and filled with emotion and movement. In these fountains, sculpture became the principal element, and the water was used simply to animate and decorate the sculptures. They, like baroque gardens, were "a visual representation of confidence and power."[6]

The most famous Roman fountains of this period include:

- The Fountains of St. Peter's Square, by Carlo Maderno (1614) and Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1677) were made to complement the lavish Baroque facade Maderno designed for St. Peter's Basilica. The Maderno fountain was built on the site of an earlier fountain from 1490, and used the same lower basin. The Bernini fountain was added a half-century later.

- The Triton Fountain in the Piazza Barberini (1642), by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, is a masterpiece of Baroque sculpture, representing Triton, half-man and half-fish, blowing his horn to calm the waters, following a text by the Roman poet Ovid in the Metamorphoses.

- Piazza Navona is a grand theater of water – it has three fountains, built in a line on the site of the Stadium of Domitian. The fountains at either end are by Giacomo della Porta; the Neptune fountain to the north, (1572) shows the God of the Sea spearing an octopus, surrounded by Tritons, sea horses and mermaids. At the southern end is La Fontana del Moro, a figure either of an African (a Moor) or of Neptune wrestling with a dolphin. In the center is the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, (The Fountain of the Four Rivers) (1648–51), a highly theatrical fountain by Bernini, with statues representing rivers from the four continents; the Nile, Danube, Plate River and Ganges. Over the whole structure is a 54-foot (16 m) Egyptian obelisque, crowned by a cross with the emblem of the Pamphili family, representing Pope Innocent X, whose family palace was on the piazza.

- The Trevi Fountain is the largest and most spectacular of Rome's fountains, designed to glorify the three different Popes who created it. It was built beginning in 1730 at the terminus of the reconstructed Acqua Vergine aqueduct, on the site of Renaissance fountain by Leon Battista Alberti. It was the work of architect Nicola Salvi and the successive project of Pope Clement XII, Pope Benedict XIV and Pope Clement XIII, whose emblems and inscriptions are carried on the attic story, entablature and central niche. The central figure is Oceanus, the personification of all the seas and oceans, in an oyster-shell chariot, surrounded by Tritons and Sea Nymphs.

The fountains of Rome all operated purely by gravity- the source of water had to be higher than the fountain itself, and the difference in elevation and distance between the source and the fountain determined how high the fountain could shoot water. The fountain in St. Peter's Square was fed by the Paola aqueduct, restored in 1612, whose source was 266 feet (81 m) above sea level, which meant it could shoot water twenty feet up from the fountain. The Triton fountain benefited from its location in a valley, and the fact that it was fed by the Aqua Felice aqueduct, restored in 1587, which arrived in Rome at an elevation of 194 feet (59 m) above sea level (fasi), a difference of 130 feet (40 m) in elevation between the source and the fountain, which meant that the water from this fountain jetted sixteen feet straight up into the air from the conch shell of the Triton.[7]

The fountains of Piazza Navona, on the other hand, took their water from the Acqua Vergine, which had only a 23-foot (7.0 m) drop from the source to the fountains, which meant the water could only fall or trickle downwards, not jet very high upwards. For the Trevi Fountain, the architect Nicola Salvi compensated for this problem by sinking the fountain down into the ground, and by carefully designing the cascade so that the water churned and tumbled, to add movement and drama.[8]

Today all of the fountains have been rebuilt, and the Roman water system uses both gravity and mechanical pumps. Water is recycled and water from different aqueducts is sometimes mixed before it reaches the fountains and performs for the spectators.[9]

This (incomplete) list contains important fountains in the city:

Monumental fountains

[edit]These fountains were built at the termini of the restored aqueducts of Rome, to supply water to the population and to glorify the Popes who built them.

- The Trevi Fountain

- Fontana dell'Acqua Felice in the Quirinal District, by Domenico Fontana (1585–86)

- Fontana dell'Acqua Paola (Gianicolo, Via Garibaldi) (1610–1612)

- Fontana di Trevi, (Trevi Fountain) (1732–1762)

Decorative fountains

[edit]These fountains were linked to the restored aqueducts, decorated the piazzi, or squares, of Rome, and provided drinking water to the population around the squares.

- the Fountain in Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere (1499–1659)

- Fontana delle Api (Fountains of the Bees) (1644)

- Fontana di Piazza d'Aracoeli, (1589)

- Fontana dell'Acqua Acetosa

- Fontana della Barcaccia, (1627)

- Fountain in Campo de' Fiori

- Fontana di Piazza Colonna (1577 - 19th century print)

- Fontana dei Dioscuri (1818)

- One of the two twin Fontane di Piazza Farnese, in front of the Palazzo Farnese (16th century)

- La Fontana del Moro in Piazza Navona (1575)

- Fountain of the Piazza dei Monti, by Giacomo Della Porta, (1589) illustration from Fontane di Roma by Giovanni Batista Falda, about 1670

- Fountain of Neptune, Rome, Piazza Navona (1574/1878)

- Fontana del Nettuno (Fountain of Neptune), Piazza del Popolo (Fountain 1574, Neptune added 1878)

- Fontana dell Obelisco, Piazza del Popolo (assumed about 1828)

- Fontana delle Naiadi on Piazza della Repubblica (1888)

- Fontana del Pantheon (1575)

- Fontana della Pigna (1st century AD)

- Fountains of St. Peter's Square by Carlo Maderno (1614) and Bernini (1677)

- Fontana delle Tartarughe, (The Turtle Fountain) Piazza Mattei (1588)

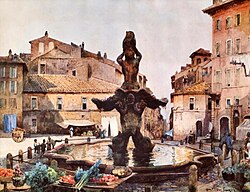

- Fontana del Tritone, Piazza Barberini (1642–43)

- Fontana delle Anfore (Fountain of the Amphorae), in Piazza dell'Emporio, near the Ponte Sublicio, by Pietro Lombardi (1927)

- Fontana di Piazza d'Aracoeli in Piazza d'Aracoeli, at the base of the Capitoline Hill (1589)

- Fontana dell'Acqua Acetosa

- Fontana delle Api (Fountain of the Bees) in the Piazza Barberini, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1644).

- Fontana della Barcaccia (Fountain of the Old Boat), Piazza di Spagna (1627)

- Fontana di Piazza Colonna in the Piazza Colonna, (completed 1577)

- Fontana dei Dioscuri in front of the resident of the President of Italy in the Piazza del Quirinale (1818)

- Fountain of Valle Giulia

- Twin Fontane di Piazza Farnese in front of the Palazzo Farnese, in Piazza Farnese (16th century)

- La Fontana del Moro, Piazza Navona, fountain by Giacomo Della Porta, (1575), statue of Moor by Bernini added in 1653)

- Fontana delle Naiadi, (Fountain of the Naiades), Piazza della Repubblica, (1870–1901)

- Nasone - iconic type of drinking water fountain

- Fontana del Nettuno, Piazza del Popolo

- Fontana del Nettuno, Piazza Navona, (1574)

- Fontana di Piazza Nicosia, originally in Piazza del Popolo,(1572), moved to Piazza Nicosia in 1823.

- Fontana del Pantheon, by Giacomo Della Porta (1575, with Egyptian obelisk added in 1711)

- Fontana del Pianto designed by Giacomo della Porte in 1590

- Fontana della Pigna (Pine Cone Fountain), in the Cortile della Pigna of Vatican City. (Sculpture from 1st century, moved to present site in 1608).

- Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Fountain of the Four Rivers), Piazza Navona (1648–1651)

- Fontana della Piazza dei Quiriti in Piazza dei Quiriti, (1927–28).

- Fontana del Tritone, (Triton Fountain) Piazza Barberini (1642–43)

- Fontana delle Tartarughe, (The Turtle Fountain), Piazza Mattei (1585–1588)

- Fountains in the garden of Villa Medici – several garden fountains

Talking statues of Rome

[edit]- Marphurius, or Marforio

- Il Babuino (The Baboon), one of the so-called "Talking statues of Rome" and fountain in via del Babuino (1581)

- Il Facchino (The Water Porter), one of the Talking statues of Rome, on Via Lata (about 1580).

- Marphurius. Roman statue of a river god or Oceanus from 1st century, fountain from 1592.

Wall fountains

[edit]- Fontana dei Libri (Fountain of the Books) (1927)

- Fontana del Mascherone (Big Mask Fountain), Via Giulia, (1626)

- The Quattro Fontane (the Four Fountains) (1588–1593)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pulvers, Marvin (2002). Roman Fountains. 2000 Fountains in Rome. A complete collection. Roma: L'Erma di Bretschneider. p. 926. ISBN 9788882651763.

- ^ "Italian culture and history: Fountain of Rome". Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ Frontin, Les Aqueducs de la ville de Rome, translation and commentary by Pierre Grimal, Société d'édition Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1944.

- ^ Pinto, John A. The Trevi Fountain. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1986.

- ^ The fountain in Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere originally had two upper basins, but the water pressure in the early Renaissance was so low that the water was unable to reach the upper basin, so the top basin was removed.

- ^ Italian Gardens, a Cultural History, Helen Attlee. Francis Lincoln Limited, London 2006.

- ^ Katherine Wentworth Rinne, The Fall and Rise of the Waters of Rome, collected in Marilyn Symmes, 'Fountains- Splash and Spectacle – Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present,. Thames and Hudson, London, 1998 (pg. 54).

- ^ Maria Ann Conneli and Marilyn Symmes, Fountains as propaganda, in Fountains, Splash and Spectacle – Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present. Edited by Marilyn Symmes. Thames and Hudson, London, and Katherine Wentworth Rinne, The Fall and Rise of the Waters of Rome, in the same collection.

- ^ Katherine Wentworth Rinne, collected in Marilyn Symmes, Fountains- Splash and Spectacle. (pg. 54).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch