Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan

| Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (日本国とアメリカ合衆国との間の相互協力及び安全保障条約) | |

|---|---|

Treaty signature page (Japanese-language copy) | |

| Type | Military alliance |

| Signed | January 19, 1960 |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Effective | June 23, 1960 |

| Parties | |

| Citations | 11 U.S.T. 1632; T.I.A.S. No. 4509 |

| Language | English, Japanese |

| Full text | |

The Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (日本国とアメリカ合衆国との間の相互協力及び安全保障条約, Nihon-koku to Amerika-gasshūkoku to no Aida no Sōgo Kyōryoku oyobi Anzen Hoshō Jōyaku), more commonly known as the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty in English and as the Anpo jōyaku (安保条約) or just Anpo (安保) in Japanese, is a treaty that permits the presence of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil, and commits the two nations to defend each other if one or the other is attacked "in the territories under the administration of Japan". Over time, it has had the effect of establishing a military alliance between the United States and Japan.

The current treaty, which took effect on June 23, 1960, revised and replaced an earlier version of the treaty, which had been signed in 1951 in conjunction with the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty that terminated World War II in Asia as well as the U.S.-led Occupation of Japan (1945–1952). The revision of the treaty in 1960 was a highly contentious process in Japan, and widespread opposition to its passage led to the massive Anpo protests, which were the largest popular protests in Japan's history.[1]

The 1960 treaty significantly revised the U.S.-Japan security agreement in the direction of greater mutuality between the two nations. The original 1951 treaty had contained a provision permitting the United States to use forces based in Japan throughout East Asia without prior consultation with Japan, made no explicit promise to defend Japan if Japan were attacked, and even contained a clause allowing U.S. troops to intervene in Japanese domestic disputes.[2] These portions were altered in the revised version of the treaty in 1960. The amended treaty included articles delineating mutual defense obligations and requiring the US, before mobilizing its forces, to inform Japan in advance.[3] It also removed the article permitting U.S. interference in Japanese domestic affairs.[3]

The treaty also included general provisions for the further development of international understanding and improved economic collaboration between the two nations. These provisions became the basis for the establishment of the United States–Japan Conference on Cultural and Educational Interchange (CULCON), the United States–Japan Committee on Scientific Cooperation, and the Joint United States–Japan Committee on Trade and Economic Affairs, all three of which are still in operation in some form.[4]

The U.S.-Japan Security Treaty has never been amended since 1960 and thus has lasted longer in its original form than any other treaty between two great powers since the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.[5] The treaty had a minimum term of 10 years, but provided that it would remain in force indefinitely unless one party gives one year's notice of wishing to terminate it.

Background

[edit]

The original U.S.-Japan Security Treaty had been forced on Japan by the United States as a condition of ending the U.S.-led military occupation of Japan following the end of World War II.[2] It was signed on September 8, 1951, in tandem with the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty ending World War II in Asia, and went into effect on April 28, 1952, in tandem with the end of the occupation of Japan.[2] The original Security Treaty had no specified end date or means of abrogation, allowed US forces stationed in Japan to be used for any purpose anywhere in the "Far East" without prior consultation with the Japanese government, and had a clause specifically authorizing US troops to put down domestic protests in Japan. Perhaps most gallingly of all, the pact did not contain an article committing the United States to defend Japan if Japan were attacked by a third party.[2]

The Japanese government began pushing for a revision to the treaty as early as 1952. However, the administration of U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower resisted calls for revision until a growing anti-U.S. military base movement in Japan culminated in the Sunagawa Struggle of 1955-1957 and popular outrage in Japan in the aftermath of the Girard Incident in 1957, which made deep dissatisfaction with the status quo more apparent.[6] The United States agreed to a revision, negotiations began in 1958, and the new treaty was signed by Eisenhower and Kishi at a ceremony in Washington, D.C., on January 19, 1960.[7]

From a Japanese perspective, the new treaty was a significant improvement over the original treaty, committing the United States to defend Japan in an attack, requiring prior consultation with the Japanese government before dispatching US forces based in Japan overseas, removing the clause preauthorizing suppression of domestic disturbances, and specifying an initial 10-year term, after which the treaty could be abrogated by either party with one year's notice.[8]

Because the new treaty was superior to the old one, Kishi expected it to be ratified in relatively short order. Accordingly, he invited Eisenhower to visit Japan beginning on June 19, 1960, in part to celebrate the newly ratified treaty. If Eisenhower's visit had proceeded as planned, he would have become the first sitting US president to visit Japan.[9]

Terms

[edit]In Article 1, the treaty began by establishing that each country would seek to resolve any international disputes peacefully. The treaty also gave prominence to the United Nations in dealing with aggression.

Article 2 generally called for greater collaboration between the two nations in terms of international relations and economics. At a summit meeting between U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Japanese Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda in June 1961, this clause was put into action with the formation of three cabinet level consultative committees - the United States–Japan Conference on Cultural and Educational Interchange (CULCON), the United States–Japan Committee on Scientific Cooperation, and the Joint United States–Japan Committee on Trade and Economic Affairs, all three of which are still in operation in some form.[4]

Article 3 commits both the US and Japan to maintain and develop their armed forces and resist attack.

Article 4 suggests that the United States will consult with Japan in some manner on how it uses the U.S. troops based in Japan.

Article 5 commits the United States to defend Japan if it is attacked by a third party.

Article 6 explicitly grants the United States the right to base troops in Japan, subject to a detailed "Administrative Agreement" negotiated separately.

Article 7 states that the treaty does not affect the US or Japan's rights and obligations under the Charter of the United Nations.

Article 8 states that the treaty will be ratified by the US and Japan in accordance with their respective constitutional processes and will go into effect the date they are signed and exchanged in Tokyo.

Article 9 states that the prior treaty signed in San Francisco in 1951 shall expire when the current treaty takes effect.

Article 10 allows for the abrogation of the treaty, after an initial 10-year term, if either party gives one year's advance notice to the other of its wish to terminate the treaty.

The agreed minutes to the treaty specified that the Japanese government would be consulted prior to major changes in United States force deployment in Japan or to the use of Japanese bases for combat operations other than to defend Japan itself. Also covered were the limits of both countries' jurisdictions over crimes committed in Japan by US military personnel.

Popular opposition

[edit]

Although the 1960 treaty was manifestly superior to the original 1951 treaty, many Japanese from across the political spectrum resented the presence of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil and hoped to get rid of the treaty entirely.[10] An umbrella organization, the People's Council for Preventing Revision of the Security Treaty (安保条約改定阻止国民会議, Anpo Jōyaku Kaitei Soshi Kokumin Kaigi), was formed in 1959 to coordinate the actions of various citizen movements involved in opposing ratification of the revised treaty.[11] The People's Council initially consisted of 134 member organizations in March 1959 and grew to have 1,633 affiliated organizations by March 1960. Member groups included labor unions, farmers' and teachers' unions, poetry circles, theater troupes, student and women's organizations, mothers' groups, groups affiliated with the Japan Socialist Party and the Japan Communist Party, and even some conservative business groups.[11] In total the People's Council carried out 27 separate events of nationwide mass protest from March 1959 to July 1960.[12]

Faced with popular opposition in the streets and Socialist Party stonewalling in the National Diet, Prime Minister Kishi grew increasingly desperate to pass the treaty in time for Eisenhower's scheduled arrival in Japan on June 19.[13] Finally on May 19, 1960, in the so-called "May 19 Incident," Kishi suddenly called for a snap vote on the treaty.[13] When Socialist Diet members attempted a sit-in to block the vote, Kishi introduced 500 policemen into the Diet and had them physically removed from the halls of the Diet by police, and rammed the treaty through with only members of his own party present.[14]

Kishi's actions were widely perceived as anti-democratic, and provoked nationwide outrage from across the political spectrum.[15] Thereafter, the anti-treaty protests swelled to massive size, with the Sōhyō labor federation carrying out a series of nationwide strikes involving millions of labor unionists, large crowds marching in cities and towns throughout the nation, and tens of thousands of protesters gathering around the National Diet on nearly a daily basis.[15] On June 10, in the so-called Hagerty Incident, thousands of protesters mobbed a car carrying Eisenhower's press secretary James Hagerty, slashing its tires, smashing its tail lights, and rocking it back and forth for more than an hour before the occupants were rescued by a U.S. Marine Corps helicopter.[16] Finally on 15 June 1960, the radical student activists from the Zengakuren nationwide student federation attempted to storm the Diet compound itself, precipitating a fierce battle with police in which a female Tokyo University student named Michiko Kanba was killed.[17]

Desperate to stay in office long enough to host Eisenhower's visit, Kishi hoped to secure the streets in time for Eisenhower's arrival by calling out the Japan Self Defense Forces[18] and tens of thousands of right-wing thugs that would be provided by his friend, the yakuza-affiliated right-wing "fixer" Yoshio Kodama.[19] However, he was talked out of these extreme measures by his cabinet, and thereafter had no choice but to cancel Eisenhower's visit, for fears that his safety could not be guaranteed, and to announce his own resignation as Prime Minister, in order to quell the widespread popular anger at his actions.[18]

Ratification and enactment

[edit]Despite the massive size achieved by the anti-treaty movement, the protests ultimately failed to stop the treaty. Although Kishi was forced to resign and Eisenhower's visit was cancelled, under Japanese law, the treaty was automatically approved 30 days after passing the Lower House of the Diet.[20] Article 8 of the treaty stipulated that the new treaty would immediately enter into force once ratification instruments were exchanged between Japanese and American officials in Tokyo. The instruments were officially exchanged on June 23, 1960, at which point the new treaty took effect and the old treaty expired. According to foreign minister Aiichirō Fujiyama, the official ratification instruments had to be smuggled to Kishi for his signature in a candy box, to avoid the notice of the protesters still mobbing his official residence.[20]

However, once the treaty entered into force and Kishi resigned from office, the anti-treaty protest movement lost momentum and rapidly died away.[21]

Aftermath

[edit]The anti-American aspect of the protests and the humiliating cancellation of Eisenhower's visit brought U.S.-Japan relations to their lowest ebb since the end of World War II. The new U.S. president, John F. Kennedy, appointed sympathetic Japan expert and Harvard University professor Edwin O. Reischauer as ambassador to Japan, rather than a career diplomat, and invited the new Japanese prime minister, Hayato Ikeda, to be the first foreign leader to visit the United States in his term in office.[22] At their June 1961 summit meeting, the two leaders agreed that henceforth the two nations would consult much more closely as allies, along lines similar to the relationship between the United States and Great Britain.[23] Back in Japan, Ikeda took a much more conciliatory stance toward the political opposition, indefinitely shelving Kishi's plans to revise the Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, and announcing the Income Doubling Plan with the explicit goal of redirecting the nation's energies away from the contentious treaty issue and toward a nationwide drive for rapid economic growth.[24]

The difficult process of securing the passage of the revised treaty and the violent protests it caused contributed to a culture of secret pacts (密約, mitsuyaku) between the two nations. Going forward, rather than putting contentious issues to a vote, the two nations secretly negotiated to expand the scope of the Security Treaty without allowing a vote.[25] Secret pacts negotiated in the 1960s and not brought to light until decades later allowed U.S. naval vessels carrying nuclear weapons to "transit" through Japanese ports, allowed nuclear powered U.S. vessels to vent radioactive wastewater in Japanese waters, and allowed the U.S. to introduce nuclear weapons into U.S. bases on Okinawa even after its reversion to Japan in 1972, among other secret deals.

Throughout the decade of the 1960s, left-wing activists looked forward to the end of the revised treaty's initial 10-year term in 1970 as an opportunity to try to persuade the Japanese government to abrogate the treaty. In 1970, in the wake of the 1968-1969 student riots in Japan, a number of student groups, civic groups, and the anti-Vietnam War organization Beheiren held a series of protest marches against the Security Treaty. However, prime minister Eisaku Satō (who was Kishi's younger brother) opted to ignore the protests completely and allow the treaty to automatically renew. Since that time, no attempt has been made to abrogate the treaty by either party, and U.S. bases remain a fixture on Japanese soil. As of 2010, there were still some 85 facilities housing 44,850 U.S. military personnel and 44,289 dependents.[5]

Ongoing opposition in Okinawa

[edit]

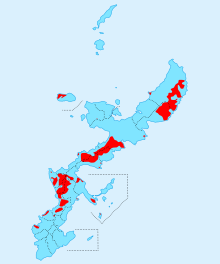

A central issue in the debate over the continued U.S. military presence is the heavy concentration of troops in the small Japanese prefecture of Okinawa. U.S. military bases cover about one fifth of Okinawa and house around 75% of the U.S. forces in Japan.[26][5] Base-related frictions, disputes, and environmental problems have left many Okinawans feeling that while the security agreement may be beneficial to the United States and Japan as a whole, they bear a disproportionate share of the burden.[26]

One contentious issue to many Okinawans is the noise and environmental pollution created by the US forces in Japan. Prolonged exposure to high-decibel noise pollution from the American military jets flying over residential areas in Okinawa has been found to cause heart problems, disrupt sleep patterns, and damage cognitive skills in children.[27] Excessive noise lawsuits filed in 2009 by Okinawa's residents against Kadena Air Base and Marine Corps Air Station Futenma resulted in awards of $57 million and $1.3 million to residents, respectively.[28][29] Toxic chemical runoff from U.S. bases, live-fire drills using depleted uranium rounds, and base construction and expansion activities have polluted Okinawa's water supply and damaged Okinawa's once-pristine coral reefs, reducing their economic value for fishing and tourism.[27][30]

The most powerful opposition in Okinawa, however, stemmed from criminal acts committed by US service members and their dependents, with the latest example being the 1995 kidnapping and molestation of a 12-year-old Okinawan girl by two Marines and a Navy corpsman.[5] In early 2008, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice apologized after a series of crimes involving American troops in Japan, including the rape of a girl of 14 by a marine on Okinawa. The US military also imposed a temporary 24-hour curfew on military personnel and their families to ease the anger of local residents.[31]

These grievances, among others, have sustained a large and enduring anti-Security Treaty movement in Okinawa.

Public support

[edit]Despite the strong Okinawan opposition to the US military presence on the island, there is support for the agreement in Japan as a whole. Although views of the treaty were fiercely polarized when the treaty was first approved in 1960, acceptance of the U.S.-Japan alliance has grown over time. According to a 2007 poll, 73.4% of Japanese citizens appreciated the presence of U.S. forces in Japan.[32] The manga series Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership was designed to stimulate a positive public opinion about the partnership.[33]

Treaty coverage

[edit]In 2012, the US clarified in a statement regarding the Senkaku Islands dispute that the treaty covers the Senkaku Islands and requires the Americans to defend them.[34]

On April 19, 2019, Japan and the United States confirmed that cyberattacks are also covered by the treaty. The two nations also promised to increase defense cooperation for outer space warfare, cyberwarfare, and electronic warfare.[35]

See also

[edit]- Anpo protests

- U.S.–Japan Alliance

- Japan–United States relations

- United States Forces Japan

- Defence policy of Japan

- Security Treaty between the United States and Japan

- Nuclear umbrella

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Kapur 2018, p. 11.

- ^ a b Kapur 2018, p. 18.

- ^ a b Kapur 2018, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d Packard 2010.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 21.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 35.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 12–19.

- ^ a b Kapur 2018, p. 19.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 20.

- ^ a b Kapur 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Kapur 2018, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 29.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 30.

- ^ a b Kapur 2018, p. 33.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 250.

- ^ a b Kapur 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 34.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 75–107.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 68.

- ^ a b Sumida 2009c.

- ^ a b Shorrock 2021.

- ^ Sumida 2009a.

- ^ Sumida 2009b.

- ^ Mitchell 2020.

- ^ Justin McCurry (February 28, 2008). "Condoleezza Rice apologizes for US troops behavior on Okinawa as crimes shake alliance with Japan". The Guardian. UK.

- ^ 自衛隊・防衛問題に関する世論調査 Archived 2010-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, The Cabinet Office of Japan

- ^ Our Alliance - A Lasting Partnership. January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Panetta tells China that Senkakus under Japan-U.S. Security Treaty". The Asahi Shimbun. September 21, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ "US to defend Japan from cyberattack under security pact". The Mainichi. 20 April 2019. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

Sources cited

[edit]- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674984424.

- Mitchell, Jon (October 12, 2020). "US Military Bases Are Poisoning Okinawa". The Diplomat. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- Packard, George R. (2010). "The United States-Japan Security Treaty at 50: Still a Grand Bargain?". Foreign Affairs. 89 (2): 92–103. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- Shorrock, Tim (April 27, 2021). "The Toxic Legacy of the US Military in the Pacific". The Nation. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- Sumida, Chiyomi (2009a). "$57 Million Awarded in Kadena Noise Suit". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- Sumida, Chiyomi (2009b). "Japan High Court Hears Arguments in Futenma Noise Pollution Lawsuit". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- Sumida, Chiyomi (2009c). "Futenma Questions and Answers". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch