United States Court for China

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

| United States Court for China | |

|---|---|

| Defunct | |

| |

| Location | Shanghai International Settlement |

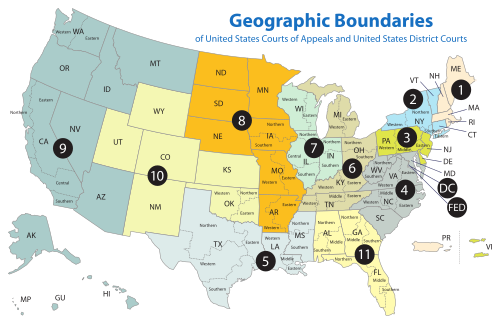

| Appeals to | Ninth Circuit |

| Established | June 30, 1906 |

| Abolished | May 20, 1943 |

| United States Court for China | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 美國中國事務法院 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 美国中国事务法院 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 上海美國法院 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 上海美国法院 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Shanghai American Court | ||||||

| |||||||

The United States Court for China was a United States district court that had extraterritorial jurisdiction over U.S. citizens in China. It existed from 1906 to 1943 and had jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters, with appeals taken to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco.

Consular courts prior to establishment of court

[edit]Extraterritorial jurisdiction in China was first granted to the United States by the Treaty of Wanghia upon ratification in 1845,[1] followed by the Treaty of Tientsin ratified in 1860.

Under the treaties, cases against US citizens were tried in US consular courts, while cases against Chinese nationals were tried in Chinese courts.[2] Consuls had jurisdiction in the following matters:

- criminal cases where the punishment for the offense charged did not exceed a $100 fine or 60 days imprisonment, from which there was no appeal;[3]

- criminal cases where the punishment for the offense charged did not exceed a $500 fine or 90 days imprisonment, from which an appeal was available to the commissioner of the United States in China;[4] and

- civil cases, in which those for damages not exceeding $500 were generally not subject to appeal.[5]

The commissioner had jurisdiction to hear all cases, and could prescribe rules of civil and criminal procedure for the consuls to follow.[6]

Establishment of court

[edit]

The court was established in 1906 by the Act Creating a United States Court for China.[7] The court was similar in structure to the British Supreme Court for China and Corea that had been established in Shanghai in 1865.

The court was originally headquartered in the American Consulate General building on Huangpu Road in the Shanghai International Settlement, with additional sessions held at least annually in the Chinese cities of Guangzhou, Tianjin, and Hankou. The court moved with the US Consulate when the consulate was moved from its previous premises in the years 1911, 1930 and 1936.

The court had only one full-time judge, and those on trial sometimes had to wait months for proceedings. In the 1930s, the law was amended to allow the appointment of special judges, allowing trials to proceed in the judge's absence. Appeals were allowed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.[8]

The U.S. consular courts in China retained limited jurisdiction, including civil cases where property involved in the controversy did not exceed $500 and criminal cases where the punishment did not exceed $100 in fines or 60 days' imprisonment.[9] The Court exercised appellate jurisdiction over them, as well as, until 1910 when Japan annexed Korea, US Consular Courts in Korea.

Jurisprudence

[edit]The court's jurisdiction was given an expansive interpretation:

- while the treaty strictly covered only US citizens, the court assumed jurisdiction over US non-citizen nationals who originated from "possessions" (i.e. colonies) such as the Philippines[10] and Guam.[11]

- even where the State Department discriminated against Chinese-Americans living abroad in China, the court held that "an American citizen in China, whether residing temporarily or permanently, remains as much under the jurisdiction of his government, its laws and its institutions as if he were residing at home."[12]

- it enforced consular title deeds where US citizens held land in trust for Chinese beneficiaries.[13]

- in divorce and annulment cases, only the plaintiff had to be an American resident in China: there were no residency or nationality requirements for defendants.[14]

The sources of law drawn upon by the court were quite varied:

- Because the court was based outside of the United States, the United States Constitution did not apply; there was no right to a jury trial nor to constitutional due process.[15]

- It was also provided that where "the laws of the United States ... are deficient in the provisions necessary to give jurisdiction or to furnish suitable remedies, the common law and the law as established by the decisions of the courts of the United States shall be applied."[16]

- The municipal regulations of the Shanghai International Settlement were also recognized and given effect.[17]

- Traditional Chinese law was applied by the court in some cases, as well as local "compradore" or "Chinese custom."[17]

The question as to what constituted "common law" led to severe difficulties, because U.S. federal law did not cover many criminal offenses or civil matters (which were normally provided for by U.S. state law). The Ninth Circuit provided a solution to this conundrum in the case of Biddle v. United States,[18] where it was held that the laws of the Territory of Alaska or the District of Columbia were federal law and could be applied by the court.[note 1] As a result, Judge Lobingier would later hold that "there can be no half way adoption of that doctrine; it includes all such laws or none. It cannot logically be restricted to any particular class of acts. It is just as applicable to civil laws as to criminal; just as 'necessary' in respect to corporations as to procedure."[20]

The court prescribed its own rules for procedures to be followed.[21] This was in contrast to the situation in the States, where civil procedure in actions at law (i.e., most lawsuits for monetary damages) in U.S. federal courts was normally provided for by state law, by virtue of the Conformity Act of 1872,[22] until the promulgation of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in 1938.

The United States Congress also passed several statutes conferring specific powers on the court:

- An Act to Regulate the Practice of Pharmacy and the Sale of Poison in the Consular Districts of the United States in China, Pub. L. 63–262, 38 Stat. 817, enacted March 3, 1915

- China Trade Act, 1922, Pub. L. 67–312, 42 Stat. 849, enacted September 19, 1922, as amended by Pub. L. 68–484, 43 Stat. 995, enacted February 26, 1925

Court seal

[edit]

The act establishing the court provided: "The seal of the United States Court for China shall be the arms of the United States, engraved on a circular piece of steel of the size of a half dollar, with these words in the margin 'The Seal of the United States Court for China'". The seal was to be used to seal all writs, processes and other documents issued by the court.

Imprisonment

[edit]

People who received relatively short sentences for criminal offences were either imprisoned in the Consular Gaol in the consulate or in either Ward Road Gaol or Amoy Road Gaol, both run by the Shanghai Municipal Council. Those serving longer sentences were sent to Bilibid Prison in the Philippines and later from the 1920s were generally sent to the federal penitentiary at McNeil Island in Washington State to serve their sentence.[23]

Abolition

[edit]

The United States Consulate and Court in Shanghai were occupied by the Japanese on December 8, 1941, at the beginning of the Pacific War. The Judge and other staff were interned for 6 months before being repatriated.[24]

Americans continued to enjoy extraterritorial rights in those parts of China not occupied by the Japanese. On January 11, 1943, the U.S. and China signed the Treaty for Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China, thereby relinquishing all U.S. extraterritorial rights. The treaty was ratified by the United States Senate and came into force on May 20, 1943. As a result, both the U.S. Court for China and the U.S. Consular Courts in China were abolished. However, their judgments continued to serve as res judicata within China.

The last case before the court was heard in Kunming starting on 14 January 1943. Boatner Carney of the Flying Tigers was prosecuted for manslaughter before Special Judge Bertrand E. Johnson. Carney was convicted of unlawful killing and sentenced to two years imprisonment.[25] He was pardoned 6 months later by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Judges

[edit]Substantive appointments

[edit]| Person | Term | Background | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lebbeus R. Wilfley | 1906–1908 | Attorney and former Attorney General of the Philippines. |

| Rufus Hildreth Thayer | 1909–1913 | Lawyer, law clerk in the US Department of Treasury, assistant to the Librarian of Congress and former Advocate General of the District of Columbia National Guard[26] |

| Charles S. Lobingier | 1914–1924 | Law professor, former Judge of the Philippines Court of First Instance and later member of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission |

| Milton D. Purdy | 1924–1934 | Former city and county attorney, US Attorney and Assistant U.S. Attorney General |

| Milton J. Helmick | 1934–1943 | Former judge and Attorney General of New Mexico |

Special Judges

[edit]Two individuals were also appointed Special Judges of the Court to try cases when the Judge was not available. They were:

- Nelson Lurton (1938 and 1941)

- Bertrand E Johnson (1943)

Commissioners

[edit]- 1918–1920: Nelson Erroll Lurton (1883–1956)

- 1920–1923: Ferno J. Schul (1889-??)

- 1923–1928: Nelson Erroll Lurton (1883–1956)

- 1928–1933: Alexander Krisel (1890–1983)

- 1934-1937: William T. Collins (ex-officio as Clerk of the Court)

- 1937–1941: Nelson Errol Lurton (1883–1956)

Notable Attorneys

[edit]The following attorneys of note were admitted to practice before the court:

- Thomas R. Jernigan, former US Consul General in Shanghai

- Stirling Fessenden, Chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Council (1923–1929); Secretary-General of the SMC (1929–1939)

- Cornell Franklin, Chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Council (1937–1938)

- Norwood Allman, Member of the Shanghai Municipal Council (1940–1942)

- Edwin Cunningham, United States Consul General in Shanghai from 1920 to 1935 was admitted to the bar of the court in 1930, but did not practice before the court

- Addie Viola Smith, Trade commissioner in Shanghai (1928–1939)[27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Judge Charles S. Lobingier gave detailed evidence on the workings of, and application of law by, the court and extraterritoriality in China to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in 1917.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ implemented in An Act to Carry Into Effect Certain Provisions in the Treaties Between the United States and China and the Ottoman Porte, Giving Certain Judicial Powers to Ministers and Consuls of the United States in Those Countries, Pub. L. 30–150, 9 Stat. 276, enacted August 11, 1848

- ^ Ruskola 2008, p. 220.

- ^ 1848 Act, s. 8

- ^ 1848 Act, s. 9

- ^ 1848 Act, s. 11

- ^ 1848 Act, s. 5

- ^ An Act Creating a United States Court for China and prescribing the jurisdiction thereof, Pub. L. 59–403, 34 Stat. 814, enacted June 30, 1906

- ^ 1906 Act, s. 3

- ^ 1906 Act, s. 2

- ^ United States v. Scogin, I Extraterritorial Cases 376 (USC-C 1914).

- ^ United States v. Osman, I Extraterritorial Cases 540 (USC-C 1916).

- ^ In re Robert Lee's Will, I Extraterritorial Cases 699, 710 (USC-C 1918).

- ^ Latter, A.M. (1903). "The Government of the Foreigners in China". Law Quarterly Review. 19: 316., at 322

- ^ Richards v. Richards, I Extraterritorial Cases 480 (USC-C 1915).

- ^ Casement v. Squier, 138 F.2d 909 (9th Cir. 1943)., citing In re Ross, 140 U.S. 453 (1891)

- ^ 1906 Act, s.4

- ^ a b Ruskola 2008, p. 233.

- ^ Biddle v. United States, 156 F. 759 (9th Cir. 1907)., reversing (on other grounds) United States v. C.A. Biddle, I Extraterritorial Cases 84, 87 (USC-C 1907).

- ^ Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, 65th Congress Sept 27 and 28 and 1 October 1917.

- ^ United States ex rel. Raven v. McRae, I Extraterritorial Cases 655, 664 (USC-C 1917).

- ^ 1906 Act, s. 5

- ^ An Act to further the Administration of Justice, Pub. L. 42–255, 17 Stat. 196, enacted June 1, 1872

- ^ Allman 1943, p. 99.

- ^ New York Times, "US Officials kept in Hotel, December 9, 1941 and "Gripsholm brings 1,500 from the Orient" August 26, 1942.

- ^ The Daily Herald (Biloxi and Gulfport), Jan 18, 1943.

- ^ "Judge R. H. Thayer Dies of Apoplexy" (PDF). New York Times. July 13, 1917.

- ^ Barker, Heather (2006) [2002]. "Addie Viola Smith (1893–1975)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Allman, Norwood Francis (1943). Shanghai Lawyer. McGraw Hill. OCLC 582340713. (Republished with annotations and Illustrations as: Shanghai Lawyer: The Memoirs of America's China Spy Master, Earnshaw Books, 2017)

- Clark, Douglas (2015). Gunboat Justice: British and American Law Courts in China and Japan (1842-1943). Hong Kong: Earnshaw Books., Vol. 1: ISBN 978-988-82730-8-9; Vol. 2: ISBN 978-988-82730-9-6; Vol. 3: ISBN 978-988-82731-9-5.

- Hinckley, Frank E. (1912). "Extraterritoriality in China". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 39: 97–108. doi:10.1177/000271621203900111. JSTOR 1012076. S2CID 144413117.

- Lee, Tahirih V. (2004). "The United States Court for China: A Triumph of Local Law". Buffalo Law Review. 52 (4). University at Buffalo Law School: 923–1075. SSRN 958954.

- Lobingier, Charles Sumner (1919). American Courts in China. Bar Association Publications.

- Lobingier, Charles Sumner (1920). Extraterritorial Cases, Including the Decisions of the United States Court for China from Its Beginning, Those Reviewing the Same by the Court of Appeals, and the Leading Cases Decided by Other Courts on Questions of Extraterritoriality. Vol. I. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

- Lobingier, Charles Sumner (1928). The Decisions of the United States Court for China, 1920-1924, Those Reviewing the Same by the Court of Appeals and Leading Decisions by Other Authorities on Questions of Extraterritoriality. Vol. II. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

- Millare, Thomas F. (March 22, 1908). "A United States Court on Foreign Soil: Excellent Results Follow Judge Wilfley's Work in the Establishment of American Law and Jurisdiction in Foreign Concession, Shanghai". The New York Times.

- Ruskola, Teemu (November 15, 2003). Law's Empire: The Legal Construction of 'America' in the 'District of China'. Annual Meeting of American Society of Legal History. Washington, DC. SSRN 440641.

- Ruskola, Teemu (2008). "Colonialism without Colonies: On the Extraterritorial Jurisprudence of the U.S. Court for China". Law and Contemporary Problems. 71 (3). Duke University School of Law: 217–242.

- Scully, Eileen P. (2001). Bargaining with the State from Afar: American Citizenship in Treaty Port China, 1842-1942. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12109-5.

- Walayat, Aaron J. (2021). "China's Alaskan Jurisprudence" (PDF). UC Davis Journal of International and Comparative Law. 28 (1): 43–63.

- Wessan, Eric H. (2020). "The United States Court for China". Green Bag 2d. 23 (Summer). The Green Bag: 297–309.

External links

[edit]Legislation

[edit]Investigations

[edit]- Charges against Lebbeus R. Wilfley, Judge of the United States Court for China, and Petition for His Removal from Office

- United States Court for China: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs (HR)

US National Archive files

[edit]- Correspondence relating to and case files of the US Court for China (M862 Roll 80)

- US Court for China case reports from 1907 (M862 Roll 81)

- Correspondence relating to the US Court for China (M862 Roll 82)

- Consular files relating to charges against Judge Wilfley and other correspondence (M862 Roll 83) Archived 2020-06-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Consular files relating to charges against Judge Wilfley with numerous newspaper clippings and transcript of R v O’Shea and appointment of Rufus Thayer (M862 Roll 84) Archived 2020-06-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Consular Files relating to US Court for China (up to p283) (M862 Roll 85)

- General consular correspondence including cases before consular courts in China and prison escape in 1906 (pp. 213 et seq) (M862 Roll 92)

- Correspondence relating to charges against Wilfley by Lorrin Andrews (up to page 232) (Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1763–2002 Series: Numerical Files, 8/1906 - 1910 File Unit: Numerical File: 4769–4787)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch

![Addie Viola Smith, Trade commissioner in Shanghai (1928–1939)[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b3/Addie_Viola_Smith.jpg/99px-Addie_Viola_Smith.jpg)