Vandal Sardinia

|

| History of Sardinia |

Vandal Sardinia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 456–534 | |||||||||

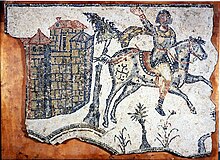

Vandal Kingdom in 476 | |||||||||

| Capital | Caralis | ||||||||

| Common languages | Vulgar Latin | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Established | 456 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 534 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Vandal Sardinia covers the history of Sardinia from the end of the long Roman domination in 456, when the island was conquered by the Vandals, a Germanic population settled in Africa Proconsularis and Mauretania Caesariensis, until its reconquest by the Byzantine Roman Emperor Justinian in 534.

Conquest

[edit]The conquest of the former province of Corsica and Sardinia by the Vandals occurred between about 456 and 460 AD, the year of the agreement between Genseric, king of the Vandals, and the emperor Majorian.[1] It was a partial, limited and short-lived occupation of some coastal cities. In 466, the Roman general Marcellinus, possibly encouraged by Pope Hilarius, succeeded in regaining control of the island. However, between 474 and 482, Sardinia fell again under the rule of the Vandals, perhaps led by Genseric or his son Huneric.[2]

During these campaigns, Olbia, one of the most prosperous Sardinian cities, was violently attacked by sea and its port destroyed.[4]

The possession of Sardinia guaranteed the Vandals secure maritime trade routes between North Africa and the rest of the Mediterranean. The island became the frontier of the Vandal Kingdom and assumed an important strategic role.[5]

Vandal administration

[edit]The Vandal administrative system did not differ much from that of the Roman period. Sardinia was overseen by a governor called a praeses, chosen from the trusted men of the royal family and resident in Caralis, who had both civil and military functions. He was assisted by a multitude of auxiliary officials including procurators, tax collectors, and conductors (real estate economists).[6]

The island territory was subdivided into many parts that were assigned partially to the crown and partially to the Vandal warriors. According to historian Hermann Schreiber, strong Vandal contingents were present in Sardinia and Corsica with the aim of garrisoning the two islands.[7] The Sardinian-Roman landowners managed to keep their lands in certain cases, in exchange for the payment of lump sums.[2] Barbagia, the central-eastern mountain area of the island, remained a semi-independent duchy, as it had been in the Roman period and would remain in the first part of the Byzantine period.

At the end of the Vandal era, groups of Mauri, who were sent to the island by the Vandals, took refuge in the mountains of Barbagia or Gerrei. From here they made raids against the Forum Traiani (Fordongianus) during the Byzantine period. The Byzantine General Solomon organized a military expedition against them in the winter of 537.

Godas rebellion

[edit]

In 533, perhaps taking advantage of a remarkable autonomy, Godas, the Vandal governor of Goth origin, proclaimed himself king of the island,[8] minting his own bronze coins.

Justinian, Roman Emperor in Constantinople, purportedly to help Godas, decided to intervene and sent an army commanded by General Belisarius and assisted by Duke Cirillus. The Byzantine force led by Belisarius was made up of 16,000 soldiers and 600 ships and headed to Africa while Duke Cyril with some 400 ships headed for Caralis.

Meanwhile, the King of Vandals, Gelimer, who was also facing a revolt in Tripoli, sent his brother Tzazo with a large contingent of 120 ships and 5,000 men to Sardinia to suppress Goda's uprising. Tzazo quickly took Caralis (where he left a small contingent), executed Godas and returned immediately to Carthage where the Byzantines had landed. Belisarius had defeated Gelimer on August 30, 533, and occupied Carthage. He was followed by Cirillus, who had failed to reach Sardinia. Tzazo and Gelimer, together with what remained of the army, marched against the Byzantines but were defeated at the Battle of Tricamarum, 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Carthage. Tzazo was killed, and Gelimer escaped capture, surrendered a few months later. Cirillus then went to Calaris, where he showed Tzazo's head impaled on a pike to the Vandals of the garrison, who immediately surrendered.[9] Thus the Vandal era in Sardinia ended in 534 and the Byzantine period began.

Religion

[edit]

The Sardinian dioceses of the Roman period – Caralis, Forum Traiani, Sulci, Turris and Sanafer (and perhaps Cornus) – remained operative under the Vandals. The bishop of Caralis, probably already at the time of the Council of Carthage in 484, had Metropolitan authority over the remaining dioceses of Sardinia and the Balearic Islands.[10]

The Sardinian church was not persecuted and was not forced into Arianism.[6] African Chalcedonian bishops under the Vandals were persecuted and exiled to Sardinia during periods of the most severe oppression of Chalcedonians by Vandals. This had some positive consequences for Sardinia, because the exiles enriched the cultural and religious life during their presence, for example importing monasticism. Among the bishops deported to the island by the Vandals were the bishop of Carthage, Fulgentius of Ruspe, and Felicianis, bishop of Hippo, who carried with him the relics of Augustine of Hippo (now preserved in Pavia).[6]

It was in this period that two Sardinians ascended to the papal throne: Pope Hilarius and Pope Symmachus.

Culture

[edit]Funeral architecture

[edit]

Vandal funerary practices have been documented by the presence of some necropolis and single burials brought to light in several island locations. The most significant information comes from the Cornus-Columbaris necropolis, which consists of 22 tombs where numerous finds from a mixed German-African matrix have been made. The funeral area of Sant'Imbenia at Alghero, the burial in Spina Santa near Sassari, and the tomb discovered at Sant'Antioco, where a man was buried with his horse, also appear to belong to the Vandal age.[11]

The historian Alberto Boscolo attributed to the Vandals the tombs with barrel vaults discovered in several island resorts, mainly in southern Sardinia. The scholar identified them as Germanic elite graves but according to other scholars they would instead be placed in the Byzantine period.[12]

Clothing

[edit]

In the Vandal era, some innovations were introduced to the island with regard to clothing. These include fibulae, buckles, and jewellery such as polyhedron earrings originating in the Germanic area.[11]

Language

[edit]There is no evidence of a Vandal superstrate in the Sardinian language, however some influences of the African Romance could date back to this historical phase such as the i prothesis in words like i-scola (school, from the Latin schola).[13]

Anthroponyms

[edit]The settlement of people of Germanic origin in Sardinia is testified by some anthroponyms such as Othila, owner of a latifundium near Fiume Santo, Iesumundus, a nine-year-old child buried in Cagliari at the beginning of the 6th century AD, Patriga, a young noblewoman buried in Cornus-Columbaris in a "capuchin tomb",[14] and Waldaric, of whom we find news in a letter addressed to Pope Gregory the Great asking him to intercede with the Byzantine Dux so that he could return to the island to his wife.[15]

In the Byzantine age the minority Germanic element appears fully integrated with the local substratum. [11]

Trade

[edit]

During the rule of the Vandals, Sardinia traded with the other territories of the kingdom, with which cultural relationships were also established. In this phase there was a resumption of the importation, among other goods, of African red slip ware, found in various sites of the island.

The fall of the Vandal kingdom in Africa around 534 AD led to a progressive decline in exports of African products and important consequences at a political level.[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Casula 1994, p. 125.

- ^ a b Casula 1994, p. 127.

- ^ "Scheda: Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Olbia con le Navi Romane". beniculturalionline.it (in Italian).

- ^ "Giovanni Pietra, I Romani a Olbia: dalla conquista della città punica all'arrivo dei Vandali. L'arrivo dei Vandali" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-27. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ^ Serra, Piras 2010, p. 517.

- ^ a b c Casula 1994, p. 128.

- ^ Schreiber 1984, p. 171.

- ^ Casula 1994, p. 133.

- ^ Casula 1994, p. 135.

- ^ Metcalfe, Alex, Fernandez-aceves, Hervin, Muresu, Marco: The Making of Medieval Sardinia, 2021,p.79

- ^ a b c A cura di Silvia Lusuardi Siena, Fonti archeologiche e iconografiche per la storia e la cultura degli insediamenti nell'Altomedievo (2003) pp. 306–310

- ^ Paolo Benito Serra, Tombe a camera in muratura con volta a botte nei cimiteri altomedievali della Sardegna(1987), p.140

- ^ "Il vandalico". sardegnacultura.it (in Italian). Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Burial of Patriga". virtualarchaeology.sardegnacultura.it. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ AA. VV 2022, p. 14.

- ^ Annarita Pontis, Ceramiche da mensa dall'Africa. La sigillata africana D (in Italian), retrieved 29 December 2023

Bibliography

[edit]- Giovanni Lilliu, Presenze barbariche in Sardegna dalla conquista dei Vandali in AA.VV., Magistra Barbaritas, 1984.

- Hermann Schreiber, I Vandali. Cavalieri nomadi alla conquista del Mediterraneo, Rizzoli, 1984.

- Francesco Cesare Casula, La Storia di Sardegna, Sassari, 1994.

- Antonio Piras (a cura di), Lingua et ingenium: Studi su Fulgenzio di Ruspe e il suo contesto, Cagliari, Sandhi, 2010.

- Sergio Liccardi, Tra Roma e i Vandali. Godas re di Sardegna, 2012.

- AA.VV., Il tempo dei Vandali e dei Bizantini. La Sardegna dal V al X secolo d.C., Nuoro, Ilisso Edizioni, 2022.

External links

[edit] Media related to Vandal Sardinia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vandal Sardinia at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch