Sierra Nevada red fox

| Sierra Nevada red fox | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Sierra Nevada red fox in Lassen Volcanic National Park, 2002 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Vulpes |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | V. v. necator |

| Trinomial name | |

| Vulpes vulpes necator Merriam, 1900 | |

| |

| Sierra Nevada red fox historical range and recent sightings | |

The Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpes vulpes necator), also known as the High Sierra fox, is a subspecies of red fox found in the Oregon Cascades and the Sierra Nevada. It is likely one of the most endangered mammals in North America. The High Sierra fox shares most of its physical characteristics with the red fox, though it is slightly smaller and has some special adaptions for travel over snow. The High Sierra fox was discovered as a subspecies in 1937, but its study lapsed for more than half a century before its populations were rediscovered beginning in 1993. This subspecies of red fox may live up to 6 years.

Description

[edit]Like other montane foxes, Sierra Nevada red foxes are somewhat smaller and lighter in weight than lowland North American red foxes. Their fur may be red, cross, or silver phase with the red phase having the greyish-blonde coloration characteristic of montane foxes.[2] All three phases occur in the Oregon Cascade and Sonora Pass populations, but only red phase individuals have been found in the Lassen population. Their foot pads are fur-covered, a common adaptation to travel over snow. Sierra Nevada red foxes are relatively long-lived compared to other red foxes, typically living five to six years. Non-invasively monitored females have either not bred or bred a minority of years.[3]

Research

[edit]

Discovery and rediscovery

[edit]Sierra Nevada red foxes are one of three fox subspecies in the montane clade of North America, occurring in the Cascade Mountains south of the Columbia River and California's Sierra Nevada range.[4][5] Joseph Grinnell identified separated montane fox populations in the Oregon Cascades, Mount Shasta, Lassen Peak, and Sierra Nevada in 1937.[6] Study then lapsed for approximately 60 to 75 years, depending on location. Rediscovery of the Lassen population began in 1993[2] followed by detection of a Sierra Nevada population at Sonora Pass in 2010[7][8][9] and rediscovery of the Oregon Cascades population began in 2011.[10] The Lassen and Sonora Pass populations are isolated from each other and it is unknown if a population remains at Mount Shasta.[3]

Sacramento Valley red fox

[edit]Genetic studies beginning in 2010 have also shown the Sacramento Valley red fox (Vulpes vulpes patwin) is a distinct subspecies more closely related to the Sierra Nevada red fox than introduced lowland red foxes present in the rest of California.[4][11][12] A relatively restricted and narrow hybrid zone between Sacramento Valley red and non-native foxes has been stable for several decades, despite the five-fold expansion of non-native red fox populations throughout the rest of lowland and coastal California. This may be due to the foxes' monogamous mating habits and highly specific mate selection.[13] A similar genetic boundary may exist between Sierra Nevada red foxes and both the Sacramento Valley red fox and the introduced lowland foxes.[14]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Range

[edit]

The extent of the Sierra Nevada red fox populations is an area of active research. In Oregon, ongoing studies at Mount Hood[15] and Central Oregon[16][17] were prompted by observations in 2012 and 2013. Recent genetic evidence also suggests range expansion into western Oregon since the 1940s.[18] In California, detections occurred in northern Yosemite National Park the winter of 2014–15,[19][20] the Stanislaus National Forest in late 2015,[21] and in Lassen Volcanic National Park in 2018.[22] The first two areas are near Sonora Pass, but it has not been confirmed the individuals are part of the Sonora Pass population.

Habitat altitude

[edit]Elevations occupied by the Sierra Nevada red fox are also an area of current research. Oregon detections have occurred between 4900 and 6500 feet, though observations of Cascade red fox in Washington suggest lower elevations may be accessed during dispersal. John Perrine's study on Lassen Peak, using 144 baited motion-sensitive cameras from 1997 to 2002, found no foxes below 4520 feet.[23][11] Historically, Grinnell's 1937 survey found occurrence from 4500 to 11,500 feet in California.[6]: 381 The fox was initially described in 1906 as occurring above 6000 feet in the high Sierra.[24]: 281

Diet

[edit]A 2005 study of the then remnant population surviving on Mount Lassen found that the foxes are nocturnal hunters whose diet is predominantly mammals, especially rodents and mule deer, supplemented by birds, insects and pinemat manzanita berries as seasonally available. Lagomorphs (hares, rabbits and pikas) were virtually absent from the foxes' diet.[23]

Status and conservation

[edit]

Documented trapping of the Sierra Nevada red fox may have begun when Moses Schallenberger of the Stephens–Townsend–Murphy Party spent the winter of 1844–45 at Donner Pass, taking an average of one red fox every two days.[25] Red fox fur was sought after by trappers during the early part of the 20th century because it was softer than that of California’s gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus).[26] The State of California banned trapping of Sierra Nevada red foxes in 1974 and listed the subspecies as threatened in 1980.[27][23]

The fox's Sierra Nevada Distinct Population Segment is estimated at 29 adults near Sonora Pass in California. The Southern Cascades Distinct Population Segment consists of an estimated 42 adults near Lassen Volcanic National Park and an unknown number of individuals in five areas of Oregon.[14] No other populations are known. Interbreeding with non-native red foxes and recruitment success are primary conservation concerns.[14][27][3]

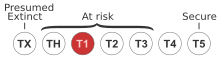

The fox is a data gap species in Oregon[28] and designated an Oregon sensitive species by the U.S. Forest Service.[29] Listing of the Southern Cascades Distinct Population Segment was found to be not warranted.[14] The Sierra Nevada Distinct Population Segment was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2021.[30]

Origin

[edit]The three subspecies in the montane clade separated after the Wisconsin glaciation, 15 to 20,000 years ago,[31] with the Columbia River perhaps dividing the Cascade and Sierra Nevada red foxes. However, prior to 2010, montane red foxes in Oregon were presumed to be the Cascade red fox.[4] Earlier literature therefore indicates incorrect ranges for the Cascade and Sierra Nevada red fox.

References

[edit]- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0".

- ^ a b John Perrine; et al. (2010). "Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes necator): A Conservation Assessment". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ a b c "Ben Sacks Lecture on Sacramento Valley and Sierra Nevada Red Fox". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2014. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ a b c Sacks, Benjamin (June 2010). "North American montane red foxes: expansion, fragmentation, and the origin of the Sacramento Valley red fox" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 11 (4): 1523–1539. Bibcode:2010ConG...11.1523S. doi:10.1007/s10592-010-0053-4. S2CID 7164254. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ Wells, Gail (2011). "Tracing the fox family tree: the North American red fox has a diverse ancestry forged during successive ice ages" (PDF) (132). Science Findings: 5. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b J. Grinnell; J. Dixon; J. Linsdale (1937). Fur-bearing mammals of California. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-7812-5041-2.

- ^ "Fox spit helped Forest Service confirm rare find". University of California, Davis. 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ "'Extinct' fox rediscovered in California". WildlifeExtra.com. September 2010. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ^ Mark J. Statham; Adam C. Rich; Sherri K. Lisius; Benjamin N. Sacks (2012). "Discovery of a remnant population of Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpes vulpes necator)" (PDF). Northwest Science. 86 (2): 122–132. Bibcode:2012NWSci..86..122S. doi:10.3955/046.086.0204. S2CID 32876374. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ Carolyn Jones (2012-06-20). "Threatened California fox species found in Oregon". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ a b John D. Perrine; John P. Pollinger; Benjamin N. Sacks; Reginald H. Barrett; Robert K. Wayne (2007). "Genetic evidence for the persistence of the critically endangered Sierra Nevada red fox in California" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 8 (5): 1083–1095. Bibcode:2007ConG....8.1083P. doi:10.1007/s10592-006-9265-z. S2CID 20629983. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ Sacks BN, Wittmer HU, Statham MJ (2010-05-30). The Native Sacramento Valley red fox. Report to the California Department of Fish and Game (PDF) (Report). p. 49. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ^ Benjamin N. Sacks; Marcelle Moore; Mark J. Statham; Heiko U. Wittmer (2011). "A restricted hybrid zone between native and introduced red fox (Vulpes vulpes) populations suggests reproductive barriers and competitive exclusion" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 20 (2): 326–341. Bibcode:2011MolEc..20..326S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04943.x. PMID 21143330. S2CID 2995171. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ a b c d "12-Month Finding on a Petition To List Sierra Nevada Red Fox as an Endangered or Threatened Species". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 8 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ "Wolverine Tracking Project 2014-5 Season Report" (PDF). Cascadia Wild. 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ "Final Progress Report: Forest Carnivore Research in the Northern Cascades of Oregon" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2014.

- ^ "Citizen Science Fall 2015 Annual Report" (PDF). Friends of the Central Cascades Wilderness. 2015-10-17. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ Statham, Mark (February 2012). "The origin of recently established red fox populations in the United States: translocations or natural range expansions?" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 93 (1): 52–65. doi:10.1644/11-MAMM-A-033.1. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "Fox photographed with remote motion-sensitive camera". National Park Service. 2015-01-28. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ^ "Rare Sierra Nevada Red Fox Caught On Camera In Yosemite National Park". The Huffington Post. 2015-01-29.

- ^ "CSERC cameras detect rare fox at new location in the Stanislaus Forest!!!". Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center. 2015-10-30. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ "They've tried for years to catch a Sierra Nevada red fox. Now scientists have caught two", The Sacramento Bee, March 18, 2018

- ^ a b c John Perrine (Fall 2005). Ecology of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) in the Lassen Peak Region of California, USA (PDF) (Thesis). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ Frank Stephens (1906). California Mammals. West Coast Publishing Co. p. 218. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

high sierra fox.

- ^ Moses Schallenberger (2007). Charles H. Todd (ed.). Moses Schallenberger at Truckey's Lake, 1844-1845. Winters, California: 19th Century Publications.

- ^ "Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpes vulpes necator)". Sierra Forest Legacy. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ a b "Mesocarnivores of Northern California: Biology, Management, & Survey Techniques" (PDF). The Wildlife Society, Northern California Chapter. 1997-08-12. pp. 55–61. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ "Oregon 2015 Conservation Plan". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ "Region 6 Forest Service Special Status Species Lists 7/21/2015". Interagency Special Status / Sensitive Species Program (ISSSSP). Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ "Sierra Nevada red fox to be listed as federally endangered". KSNV. Associated Press. 2021-08-02. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ^ Keith B. Aubry; Mark J. Statham; Benjamin N. Sacks; John D. Perrine; Samantha M. Wisely (2009). "Phyleogeography of the North American red fox: vicariance in Pleistocene forest refugia" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 18 (12): 2668–2686. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.2668A. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04222.x. PMID 19457180. S2CID 11518843. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch