Fibromyalgia

| Fibromyalgia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Fibromyalgia syndrome |

| |

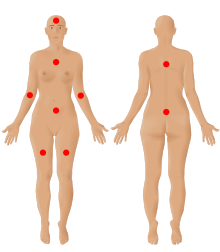

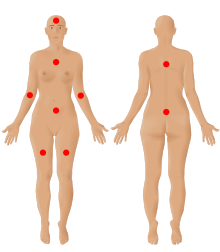

| The nine possible pain sites of fibromyalgia according to the American Pain Society. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, neurology[2] |

| Symptoms | Widespread pain, feeling tired, sleep problems[3][4] |

| Usual onset | Early-Middle age[5] |

| Duration | Long term[3] |

| Causes | Unknown[4][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other potential causes[4][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Anemia, autoimmune disorders (such as ankylosing spondylitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, or multiple sclerosis), Lyme disease, osteoarthritis, thyroid disease[6][7] |

| Treatment | Sufficient sleep and exercise[5] |

| Medication | Duloxetine, milnacipran, pregabalin, gabapentin[5][8] |

| Prognosis | Normal life expectancy[5] |

| Frequency | 2%[4] |

Fibromyalgia is a medical syndrome that causes chronic widespread pain, accompanied by fatigue, awakening unrefreshed, and cognitive symptoms. Other symptoms can include headaches, lower abdominal pain or cramps, and depression.[9] People with fibromyalgia can also experience insomnia[10] and general hypersensitivity.[11][12] The cause of fibromyalgia is unknown, but is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[4] Environmental factors may include psychological stress, trauma, and some infections.[4] Since the pain appears to result from processes in the central nervous system, the condition is referred to as a "central sensitization syndrome".[4][13] Although a protocol using an algometer (algesiometer) for determining central sensitization has been proposed as an objective diagnostic test, fibromyalgia continues to be primarily diagnosed by exclusion despite the high possibility of misdiagnosis.[14]

Fibromyalgia was first defined in 1990, with updated criteria in 2011,[4] 2016,[9] and 2019.[12] The term 'fibromyalgia' is from Neo-Latin fibro-, meaning 'fibrous tissues'; Greek μυο- myo-, 'muscle'; and Greek άλγος algos, 'pain'; thus, the term literally means "'muscle and fibrous connective tissue pain'.[15] Fibromyalgia is estimated to affect 2 to 4% of the population.[16] Women are affected about twice as often as men.[4][16] Rates appear similar across areas of the world and among varied cultures.[4]

The treatment of fibromyalgia is symptomatic[17] and multidisciplinary.[18] The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology strongly recommends aerobic and strengthening exercise.[18] Weak recommendations are given for mindfulness, psychotherapy, acupuncture, hydrotherapy, and meditative exercise such as qigong, yoga, and tai chi.[18] The use of medication in the treatment of fibromyalgia is debated,[18][19] although antidepressants can improve quality of life.[20] Other medications commonly considered helpful in managing fibromyalgia include serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and muscle relaxants.[21] Q10 coenzyme and vitamin D supplements may reduce pain and improve quality of life.[22] While symptoms of fibromyalgia are persistent in nearly all patients, they are not caused by cell damage or any organic disease.[19]

History

[edit]Chronic widespread pain had been described in the literature in the 19th century, but the term fibromyalgia was not first used until 1976, when Phillip Kahler Hench used it to describe these symptoms.[23] Many names, including muscular rheumatism, fibrositis, psychogenic rheumatism, and neurasthenia were applied historically to symptoms resembling those of fibromyalgia.[24] The term fibromyalgia was coined by researcher Mohammed Yunus as a synonym for fibrositis. and was first used in a scientific publication in 1981.[25] Fibromyalgia is from the Latin fibra (fiber)[26] and the Greek words myo (muscle)[27] and algos (pain).[28]

Historical perspectives on the development of the fibromyalgia concept note the "central importance" of a 1977 paper on fibrositis by Smythe and Moldofsky.[29][30] The first clinical, controlled study of the characteristics of fibromyalgia syndrome was published in 1981,[31] providing support for symptom associations. In 1984, an interconnection between fibromyalgia syndrome and other similar conditions was proposed,[32] and in 1986, trials of the first proposed medications for fibromyalgia were published.[32]

A 1987 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association used the term 'fibromyalgia syndrome', while saying it was a "controversial condition".[33] The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published its first classification criteria for fibromyalgia in 1990.[34] Later revisions were made in 2010,[35] 2016,[9] and 2019.[12]

Classification

[edit]Fibromyalgia is classified as a disorder of pain processing due to abnormalities in how pain signals are processed in the central nervous system.[36] The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) includes fibromyalgia in the category of "Chronic widespread pain," code MG30.01.[37] People with fibromyalgia differ in several dimensions: severity, adjustment, symptom profile, psychological profile, and response to treatment.[38]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The defining symptoms of fibromyalgia are chronic widespread pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance.[12] Other symptoms may include heightened pain in response to tactile pressure (allodynia),[12] cognitive problems,[12] musculoskeletal stiffness,[12] environmental sensitivity,[12] hypervigilance,[12] sexual dysfunction,[39] and visual symptoms.[40] Some people with fibromyalgia experience post-exertional malaise, in which symptoms flare up a day or longer after physical exercise.[41]

Pain

[edit]Fibromyalgia is predominantly a chronic pain disorder.[12] According to the NHS, widespread pain is one major symptom, which could feel like an ache, a burning sensation, or a sharp, stabbing pain.[42] Patients are also highly sensitive to pain, and the slightest touch can cause pain. Pain also tends to linger for longer when a patient experiences pain.[43]

Fatigue

[edit]Fatigue is one of the defining symptoms of fibromyalgia.[12] Patients may experience physical or mental fatigue. Physical fatigue can present as a feeling of exhaustion after exercise or limitation in daily activities.[12]

Sleep problems

[edit]Sleep problems are a core symptom of fibromyalgia.[12] These include difficulty falling or staying asleep, awakening while sleeping, and waking up feeling unrefreshed.[12] A meta-analysis compared quantitative and qualitative sleep metrics in people with fibromyalgia and healthy people. Individuals with fibromyalgia indicated lower sleep quality and efficiency, longer wake time after sleep start, shorter sleep duration, lighter sleep, and greater trouble initiating sleep when quantitatively assessed; and more difficulty initiating sleep when qualitatively assessed.[10] Sleep problems may contribute to pain by decreased release of IGF-1 and human growth hormone, leading to decreased tissue repair.[44] Improving sleep quality can help people with fibromyalgia manage pain.[45][46]

Cognitive problems

[edit]Many people with fibromyalgia experience cognitive problems (known as fibrofog or brain fog). One study found that approximately 50% of fibromyalgia patients experienced subjective cognitive dysfunction and that it was associated with higher levels of pain and other fibromyalgia symptoms.[47] The American Pain Society recognizes these problems as a major feature of fibromyalgia, characterized by trouble concentrating, forgetfulness, and disorganized or slow thinking.[12] About 75% of people with fibromyalgia report significant problems with concentration, memory, and multitasking.[48] A 2018 meta-analysis found that the largest differences between people with fibromyalgia and healthy subjects were in inhibitory control, memory, and processing speed.[48] It is hypothesized that the chronic pain in fibromyalgia compromises attention systems, resulting in cognitive problems.[48]

Hypersensitivity

[edit]In addition to hyperalgesia, patients with fibromyalgia experience hypersensitivity to other stimuli,[11] such as bright lights, loud noises, perfumes, and cold.[12] A review article found that they have a lower cold pain threshold.[49] Other studies documented an acoustic hypersensitivity.[50]

Comorbidity

[edit]Fibromyalgia as a stand-alone diagnosis is uncommon, as most fibromyalgia patients often have other chronic overlapping pain problems or mental disorders.[11] Fibromyalgia is associated with mental health issues like anxiety,[51] posttraumatic stress disorder,[4][51] bipolar disorder,[51] alexithymia,[52] and depression.[51][53][54] Patients with fibromyalgia are five times more likely to have major depression than the general population.[55] Experiencing pain and limited energy from having fibromyalgia leads to less activity, leading to social isolation and increased stress levels, which tends to cause anxiety and depression.[56]

Numerous chronic pain conditions are often comorbid with fibromyalgia.[53] These include chronic tension headaches,[51] myofascial pain syndrome,[51] and temporomandibular disorders.[51] Multiple sclerosis, post-polio syndrome, neuropathic pain, and Parkinson's disease are four neurological disorders that have been linked to pain or fibromyalgia.[53]

Fibromyalgia largely overlaps with several syndromes that may share the same pathogenetic mechanisms.[57][58] These include myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome[59][57] and irritable bowel syndrome.[58]

Comorbid fibromyalgia has been reported to occur in 20–30% of individuals with rheumatic diseases.[53] It has been reported in people with noninflammatory musculoskeletal diseases.[53]

The prevalence of fibromyalgia in gastrointestinal disease has been described mostly for celiac disease[53] and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).[53][51] IBS and fibromyalgia share similar pathogenic mechanisms, involving immune system mast cells, inflammatory biomarkers, hormones, and neurotransmitters such as serotonin. Changes in the gut biome alter serotonin levels, leading to autonomic nervous system hyperstimulation.[60]

Fibromyalgia has also been linked with obesity.[61] Other conditions that are associated with fibromyalgia include connective tissue disorders,[62] cardiovascular autonomic abnormalities,[63] obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome,[64] restless leg syndrome[65] and an overactive bladder.[66]

Risk factors

[edit]The cause of fibromyalgia is unknown.[67][68] However, several risk factors, genetic and environmental, have been identified.

Genetics

[edit]Genetics plays a major role in fibromyalgia and may explain up to 50% of the disease's susceptibility.[69] Fibromyalgia is potentially associated with polymorphisms of genes in the serotoninergic,[70] dopaminergic[70] and catecholaminergic systems.[70] Several genes have been suggested as candidates for susceptibility to fibromyalgia. These include SLC6A4,[69] TRPV2,[69] MYT1L,[69] NRXN3,[69] and the 5-HT2A receptor 102T/C polymorphism.[71] The heritability of fibromyalgia is estimated to be higher in patients younger than 50.[72]

Nearly all the genes suggested as potential risk factors for fibromyalgia are associated with neurotransmitters and their receptors.[73] Neuropathic pain and major depressive disorder often co-occur with fibromyalgia — the reason for this comorbidity appears to be due to shared genetic abnormalities, which leads to impairments in monoaminergic, glutamatergic, neurotrophic, opioid and proinflammatory cytokine signaling. In these vulnerable individuals, psychological stress or illness can cause abnormalities in inflammatory and stress pathways that regulate mood and pain. Eventually, a sensitization and kindling effect occurs in certain neurons leading to the establishment of fibromyalgia and sometimes a mood disorder.[74]

Stress

[edit]Stress may be an important precipitating factor in the development of fibromyalgia.[75] A 2021 meta-analysis found psychological trauma to be strongly associated with fibromyalgia.[76][77] People who suffered abuse in their lifetime were three times more likely to have fibromyalgia; people who suffered medical trauma or other stressors in their lifetime were about twice as likely.[76]

Some authors have proposed that, because exposure to stressful conditions can alter the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the development of fibromyalgia may stem from stress-induced disruption of the HPA axis.[78][79]

Personality

[edit]Studies on personality and fibromyalgia have shown inconsistent results.[80] Although some have suggested that fibromyalgia patients are more likely to have specific personality traits, it appears that in comparison to other diseases – when anxiety and depression are statistically controlled for – personality has far less relevance.[80]

Other risk markers

[edit]Other risk markers for fibromyalgia include premature birth, female sex, childhood cognitive and psychosocial problems, primary pain disorders, multiregional pain, infectious illness, hypermobility of joints, iron deficiency, and small-fiber polyneuropathy.[81] Metal-induced allergic inflammation has also been linked with fibromyalgia, especially in response to nickel but also inorganic mercury, cadmium, and lead.[82] Following the COVID-19 pandemic, some have suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 virus may trigger fibromyalgia.[83]

Pathophysiology

[edit]As of 2022, the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia has not yet been elucidated[84] and several theories have been suggested. The prevailing view is that fibromyalgia is a condition resulting from an amplification of pain by the central nervous system.[73] Substantial biological findings have backed up this notion, leading to development and adoption of the concept of nociplastic pain.[73]

Fibromyalgia is associated with the deregulation of proteins related to complement and coagulation cascades, as well as to iron metabolism.[85] An excessive oxidative stress response may cause dysregulation of many proteins.[85]

Nervous system

[edit]Pain processing abnormalities

[edit]Chronic pain can be divided into three categories. Nociceptive pain is pain caused by inflammation or damage to tissues. Neuropathic pain is pain caused by nerve damage. Nociplastic pain (or central sensitization) is less understood and is the common explanation of the pain experienced in fibromyalgia.[13][16][86] Because the three forms of pain can overlap, fibromyalgia patients may experience nociceptive (e.g., rheumatic illnesses) and neuropathic (e.g., small fiber neuropathy) pain, in addition to nociplastic pain.[16]

Nociplastic pain (central sensitization)

[edit]Fibromyalgia can be viewed as a condition of nociplastic pain.[87] Nociplastic pain is caused by an altered function of pain-related sensory pathways in the periphery and the central nervous system, resulting in hypersensitivity.[88]

Nociplastic pain is commonly referred to as "Nociplastic pain syndrome" because it is coupled with other symptoms.[16] These include fatigue, sleep disturbance, cognitive disturbance, hypersensitivity to environmental stimuli, anxiety, and depression.[16] Nociplastic pain is caused by either (1) increased processing of pain stimuli or (2) decreased suppression of pain stimuli at several levels in the nervous system, or both.[16]

Neuropathic pain

[edit]An alternative hypothesis to nociplastic pain views fibromyalgia as a stress-related dysautonomia with neuropathic pain features.[89] This view highlights the role of autonomic and peripheral nociceptive nervous systems in the generation of widespread pain, fatigue, and insomnia.[90] The description of small fiber neuropathy in a subgroup of fibromyalgia patients supports the disease neuropathic-autonomic underpinning.[89] However, others claim that small fiber neuropathy occurs only in small groups of those with fibromyalgia.[19]

Autonomic nervous system

[edit]Some suggest that fibromyalgia is caused or maintained by a decreased vagal tone, which is indicated by low levels of heart rate variability,[75] signaling a heightened sympathetic response.[91] Accordingly, several studies show that clinical improvement is associated with an increase in heart rate variability.[92][91][93] Some examples of interventions that increase the heart rate variability and vagal tone are meditation, yoga, mindfulness, and exercise.[75] In 2023 the Fibromyalgia: Imbalance of Threat and Soothing Systems (FITSS) model was suggested as a working hypothesis.[94] According to the FITSS model, the salience network (also known as the midcingulo-insular network) may remain continuously hyperactive due to an imbalance in emotion regulation, which is reflected by an overactive "threat" system and an underactive "soothing" system. This hyperactivation, along with other mechanisms, may contribute to fibromyalgia.[94]

Neurotransmitters

[edit]Some neurochemical abnormalities that occur in fibromyalgia also regulate mood, sleep, and energy, thus explaining why mood, sleep, and fatigue problems are commonly co-morbid with fibromyalgia.[36] Serotonin is the most widely studied neurotransmitter in fibromyalgia. It is hypothesized that an imbalance in the serotoninergic system may lead to the development of fibromyalgia.[95] There is also some data that suggests altered dopaminergic and noradrenergic signaling in fibromyalgia.[96] Supporting the monoamine related theories is the efficacy of monoaminergic antidepressants in fibromyalgia.[20] Glutamate/creatine ratios within the bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal cortex were found to be significantly higher in fibromyalgia patients than in controls and may disrupt glutamate neurotransmission.[77][97]

Neurophysiology

[edit]Neuroimaging studies have observed that fibromyalgia patients have increased grey matter in the right postcentral gyrus and left angular gyrus, and decreased grey matter in the right cingulate gyrus, right paracingulate gyrus, left cerebellum, and left gyrus rectus.[98] These regions are associated with affective and cognitive functions and with motor adaptations to pain processing.[98] Other studies have documented decreased grey matter of the default mode network in people with fibromyalgia.[99] These deficits are associated with pain processing.[99]

Neuroendocrine system

[edit]Studies on the neuroendocrine system and HPA axis in fibromyalgia have been inconsistent. The depressed function of the HPA axis results in adrenal insufficiency and potentially chronic fatigue.[100]

One study found fibromyalgia patients exhibited higher plasma cortisol, more extreme peaks and troughs, and higher rates of dexamethasone non-suppression. However, other studies have only found correlations between a higher cortisol awakening response and pain, and not any other abnormalities in cortisol.[46] Increased baseline ACTH and increase in response to stress have been observed, and hypothesized to be a result of decreased negative feedback.[96]

Oxidative stress

[edit]Pro-oxidative processes correlate with pain in fibromyalgia patients.[100] Decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, increased superoxide activity, and increased lipid peroxidation production are observed.[100] The high proportion of lipids in the central nervous system (CNS) makes the CNS especially vulnerable to free radical damage. Levels of lipid peroxidation products correlate with fibromyalgia symptoms.[100]

Immune system

[edit]Inflammation has been suggested to have a role in the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia.[101] People with fibromyalgia tend to have higher levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6,[95][102][103] and IL-8.[95][102][103] There are also increased levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 receptor antagonist.[102][103] Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines may increase sensitivity to pain, and contribute to mood problems.[104] Anti-inflammatory interleukins such as IL-10 have also been associated with fibromyalgia.[95]

A repeated observation shows that autoimmunity triggers such as traumas and infections are among the most frequent events preceding the onset of fibromyalgia.[105] Neurogenic inflammation has been proposed as a contributing factor to fibromyalgia.[106]

Digestive system

[edit]Gut microbiome

[edit]Though there is a lack of evidence in this area, it is hypothesized that gut bacteria may play a role in fibromyalgia.[107] People with fibromyalgia are more likely to show dysbiosis, a decrease in microbiota diversity.[108] There is a bidirectional interplay between the gut and the nervous system. Therefore, the gut can affect the nervous system, but the nervous system can also affect the gut. Neurological effects mediated via the autonomic nervous system as well as the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis are directed to intestinal functional effector cells, which in turn are under the influence of the gut microbiota.[109]

Gut-brain axis

[edit]The gut-brain axis, which connects the gut microbiome to the brain via the enteric nervous system, is another area of research. Fibromyalgia patients have less varied gut flora and altered serum metabolome levels of glutamate and serine,[110] implying abnormalities in neurotransmitter metabolism.[105]

Energy metabolism

[edit]Low ATP in skeletal muscle

[edit]Patients with fibromyalgia experience exercise intolerance. Primary fibromyalgia is idiopathic (cause unknown), whereas secondary fibromyalgia is in association with a known underlying disorder (such as Ankylosing spondylitis).[111][non-primary source needed] In patients with primary fibromyalgia, studies have found disruptions in energy metabolism within skeletal muscle, including: decreased levels of ATP, ADP, and phosphocreatine, and increased levels of AMP and creatine (use of creatine kinase and myokinase in the phosphagen system due to low ATP);[112][non-primary source needed] increased pyruvate;[113][non-primary source needed] as well as reduced capillary density impairing oxygen delivery to the muscle cells for oxidative phosphorylation.[114][115][non-primary source needed]

Low ATP in brain

[edit]Despite being a small percentage of the body's total mass, the brain consumes approximately 20% of the energy produced by the body.[77][non-primary source needed] Parts of the brain—the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), thalamus, and insula—were studied using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in patients with fibromyalgia and compared to healthy controls. The fibromyalgia patients were found to have lower phosphocreatine (PCr) and lower creatine (Cr) than the control group. Phosphocreatine is used in the phosphagen system to produce ATP. The study found that low creatine and low phosphocreatine were associated with high pain, and that high stress, including PTSD, may contribute to these low levels.[77][non-primary source needed]

Low phosphocreatine levels may disrupt glutamate neurotransmission within the brains of those with fibromyalgia. Glutamate/creatine ratios within the bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal cortex were found to be significantly higher than in controls.[77][97][non-primary source needed]

Diagnosis

[edit]

There is no single pathological feature, laboratory finding, or biomarker that can diagnose fibromyalgia, and there is debate over what should be considered diagnostic criteria and whether a medical diagnosis is possible, to begin with.[81] In most cases, people with fibromyalgia symptoms may have laboratory test results that appear normal and many of their symptoms may mimic those of other rheumatic conditions such as arthritis or osteoporosis. The specific diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia have evolved.[116]

American College of Rheumatology

[edit]The first widely accepted set of classification criteria for research purposes was elaborated in 1990 by the Multicenter Criteria Committee of the American College of Rheumatology. These criteria, which are known informally as "the ACR 1990", defined fibromyalgia according to the presence of the following criteria:

- A history of widespread pain lasting more than three months – affecting all four quadrants of the body, i.e., both sides and above and below the waist.

- Tender points – there are 18 designated possible tender points (although a person with the disorder may feel pain in other areas as well).

The ACR criteria for the classification of patients were originally established as inclusion criteria for research purposes and were not intended for clinical diagnosis but have later become the de facto diagnostic criteria in the clinical setting. A controversial study was done by a legal team looking to prove their client's disability based primarily on tender points and their widespread presence in non-litigious communities prompted the lead author of the ACR criteria to question now the useful validity of tender points in diagnosis.[117] Use of control points has been used to cast doubt on whether a person has fibromyalgia, and to claim the person is malingering.[23]

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology approved provisional revised diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia that eliminated the 1990 criteria's reliance on tender point testing.[35] The revised criteria used a widespread pain index (WPI) and symptom severity scale (SSS) in place of tender point testing under the 1990 criteria. The WPI counts up to 19 general body areas[a] in which the person has experienced pain in the preceding week.[9] The SSS rates the severity of the person's fatigue, unrefreshed waking, cognitive symptoms, and general somatic symptoms,[b] each on a scale from 0 to 3, for a composite score ranging from 0 to 12.[9] The revised criteria for diagnosis were:

- WPI ≥ 7 and SSS ≥ 5 OR WPI 3–6 and SSS ≥ 9,

- Symptoms have been present at a similar level for at least three months, and

- No other diagnosable disorder otherwise explains the pain.[35]: 607

In 2016, the provisional criteria of the American College of Rheumatology from 2010 were revised.[9] The new diagnosis required all of the following criteria:

- "Generalized pain, defined as pain in at least 4 of 5 regions, is present."

- "Symptoms have been present at a similar level for at least 3 months."

- "Widespread pain index (WPI) ≥ 7 and symptom severity scale (SSS) score ≥ 5 OR WPI of 4–6 and SSS score ≥ 9."

- "A diagnosis of fibromyalgia is valid irrespective of other diagnoses. A diagnosis of fibromyalgia does not exclude the presence of other clinically important illnesses."[9]

American Pain Society 2019

[edit]

In 2019, the American Pain Society in collaboration with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration developed a new diagnostic system using two dimensions.[12] The first dimension included core diagnostic criteria and the second included common features. In accordance to the 2016 diagnosis guidelines, the presence of another medical condition or pain disorder does not rule out the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Nonetheless, other conditions should be ruled out as the main explaining reason for the patient's symptoms. The core diagnostic criteria are:[14]

- Multisite pain defined as six or more pain sites from a total of nine possible sites (head, arms, chest, abdomen, upper back, lower back, and legs), for at least three months

- Moderate to severe sleep problems or fatigue, for at least three months

Common features found in fibromyalgia patients can assist the diagnosis process. These are tenderness (sensitivity to light pressure), dyscognition (difficulty to think), musculoskeletal stiffness, and environmental sensitivity or hypervigilance.[12]

Self-report questionnaires

[edit]Some research has suggested using a multidimensional approach taking into consideration somatic symptoms, psychological factors, psychosocial stressors and subjective belief regarding fibromyalgia.[118] These symptoms can be assessed by several self-report questionnaires.[9]

Widespread Pain Index (WPI)

[edit]The Widespread Pain Index (WPI) was introduced by the American College of Rheumatology in 2010. It measures the number of painful body regions.[35] The revised criteria count up to 19 general body areas: shoulder girdle, upper arm, lower arm, hip/buttock/trochanter, upper leg, lower leg, jaw, all left & right; plus the chest, abdomen, neck and upper and lower back.[35] The 2016 ACR criteria required a Widespread pain index (WPI) ≥ 7 or WPI of 4–6 for higher severity pain.

Symptom Severity Scale (SSS)

[edit]The Symptom Severity Scale (SSS) assesses the severity of the fibromyalgia symptoms.

Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ)

[edit]The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ)[119] and the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR)[120] assess three domains: function, overall impact and symptoms.[120] It is considered a useful measure of disease impact.[121]

Other questionnaires

[edit]Other measures include the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire,[122] Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, and Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale.

Differential diagnosis

[edit]As of 2009, as many as two out of every three people who are told that they have fibromyalgia by a rheumatologist may have some other medical condition instead.[123] Fibromyalgia could be misdiagnosed in cases of early undiagnosed rheumatic diseases such as preclinical rheumatoid arthritis, early stages of inflammatory spondyloarthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, myofascial pain syndromes and hypermobility syndrome.[11][124] Neurological diseases with an important pain component include multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease and peripheral neuropathy.[11][124] Other medical illnesses that should be ruled out are endocrine disease or metabolic disorder (hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, acromegaly, vitamin D deficiency), gastro-intestinal disease (celiac and non-celiac gluten sensitivity), infectious diseases (Lyme disease, hepatitis C and immunodeficiency disease) and the early stages of a malignancy such as multiple myeloma, metastatic cancer and leukemia/lymphoma.[11][124] Other systemic, inflammatory, endocrine, rheumatic, infectious, and neurologic disorders may cause fibromyalgia-like symptoms, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, psoriatic-related polyenthesitis, a nerve compression syndrome (such as carpal tunnel syndrome), and myasthenia gravis.[125][123][126][127] In addition, several medications can also evoke pain (statins, aromatase inhibitors, bisphosphonates, and opioids).[12]

The differential diagnosis is made during the evaluation based on the person's medical history, physical examination, and laboratory investigations.[125][123][126][127] The patient's history can provide some hints to a fibromyalgia diagnosis. A family history of early chronic pain, a childhood history of pain, an emergence of broad pain following physical and/or psychosocial stress, a general hypersensitivity to touch, smell, noise, taste, hypervigilance, and various somatic symptoms (gastrointestinal, urology, gynecology, neurology), are all examples of these signals.[11]

Extensive laboratory tests are usually unnecessary in the differential diagnosis of fibromyalgia.[12] Common tests that are conducted include complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and thyroid function test.[12]

Management

[edit]Universally accepted treatments typically consist of symptom management and improving patient quality of life.[17] A personalized, multidisciplinary approach to treatment that includes pharmacologic considerations and begins with effective patient education is most beneficial.[17] Developments in the understanding of the pathophysiology of the disorder have led to improvements in treatment, which include prescription medication, behavioral intervention, and exercise.

Several associations have published guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR; 2017)[18] recommends a multidisciplinary approach, allowing a quick diagnosis and patient education. The recommended initial management should be non-pharmacological, later pharmacological treatment can be added. The European League Against Rheumatism gave the strongest recommendation for aerobic and strengthening exercise. Weak recommendations were given to some treatments, based on their outcomes. Qigong, yoga, and tai chi were weakly recommended for improving sleep and quality of life. Mindfulness was weakly recommended for improving pain and quality of life. Acupuncture and hydrotherapy were weakly recommended for improving pain. A weak recommendation was also given to psychotherapy. It was more suitable for patients with mood disorders or unhelpful coping strategies. Chiropractic was strongly recommended against, due to safety concerns. Some medications were weakly recommended for severe pain (duloxetine, pregabalin, tramadol) or sleep disturbance (amitriptyline, cyclobenzaprine, pregabalin). Others were not recommended due to a lack of efficacy (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). Growth hormone, sodium oxybate, opioids, and steroids were strongly recommended against due to lack of efficacy and side effects.

The guidelines published by the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany[128] inform patients that self-management strategies are an important component in managing the disease.[129] The Canadian Pain Society[130] also published guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia.

Exercise

[edit]Exercise is the only fibromyalgia treatment that has been given a strong recommendation by the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR). There is strong evidence indicating that exercise improves fitness, sleep and quality of life and may reduce pain and fatigue for people with fibromyalgia.[131][22][132] Exercise has an added benefit in that it does not cause any serious adverse effects.[132] There are a number of hypothesized biological mechanisms.[133] Exercise may improve pain modulation[134][135] through serotoninergic pathways.[135] It may reduce pain by altering the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and reducing cortisol levels.[136] It also has anti-inflammatory effects that may improve fibromyalgia symptoms.[137][138] Aerobic exercise can improve muscle metabolism and pain through mitochondrial pathways.[137]

When different exercise programs are compared, aerobic exercise is capable of modulating the autonomic nervous function of fibromyalgia patients, whereas resistance exercise does not show such effects.[139] A 2022 meta-analysis found that aerobic training showed a high effect size while strength interventions showed moderate effects.[140] Meditative exercise seems preferable for improving sleep,[141][142] with no differences between resistance, flexibility, and aquatic exercise in their favorable effects on fatigue.[141]

Despite its benefits, exercise is a challenge for patients with fibromyalgia, due to the chronic fatigue and pain they experience.[143] They may also feel that those who recommend or deliver exercise interventions do not fully understand the possible negative impact of exercise on fatigue and pain.[144] This is especially true for non-personalized exercise programs.[144] Adherence is higher when the exercise program is recommended by doctors or supervised by nurses.[145]

Sufferers perceive exercise as more effortful than healthy adults.[146] Depression and higher pain intensity serve as barriers to physical activity.[147] Exercise may intimidate them, in fear that they will be asked to do more than they are capable of.[144]

A recommended approach to a graded exercise program begins with small, frequent exercise periods and builds up from there.[140][148] In order to reduce pain the use of an exercise program of 13 to 24 weeks is recommended, with each session lasting 30 to 60 minutes.[140]

Aerobic

[edit]Aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia patients is the most investigated type of exercise.[132] It includes activities such as walking, jogging, spinning, cycling, dancing and exercising in water,[137][139] with walking being named as one of the best methods.[149] A 2017 Cochrane summary concluded that aerobic exercise probably improves quality of life, slightly decreases pain and improves physical function and makes no difference in fatigue and stiffness.[150] A 2019 meta-analysis showed that exercising aerobically can reduce autonomic dysfunction and increase heart rate variability.[139] This happens when patients exercise at least twice a week, for 45–60 minutes at about 60%-80% of the maximum heart rate.[139] Aerobic exercise also decreases anxiety and depression and improves the quality of life.[139]

Flexibility

[edit]Combinations of different exercises such as flexibility and aerobic training may improve stiffness.[151] However, the evidence is of low-quality.[151] It is not clear if flexibility training alone compared to aerobic training is effective at reducing symptoms or has any adverse effects.[152]

Resistance

[edit]In resistance exercise, participants apply a load to their body using weights, elastic bands, body weight, or other measures.

Two meta-analyses on fibromyalgia have shown that resistance training can reduce anxiety and depression,[139][153] one found that it decreases pain and disease severity[154] and one found that it improves quality of life.[139] Resistance training may also improve sleep, with a greater effect than that of flexibility training and a similar effect to that of aerobic exercise.[155]

The dosage of resistance exercise for women with fibromyalgia was studied in a 2022 meta-analysis.[156] Effective dosages were found when exercising twice a week, for at least eight weeks. Symptom improvement was found for even low dosages such as 1–2 sets of 4–20 repetitions.[156] Most studies use moderate exercise intensity of 40% to 85% one-repetition maximum. This intensity was effective in reducing pain.[156] Some treatment regimes increase the intensity over time (from 40% to 80%), whereas others increase it when the participant can perform 12 repetitions.[156] High-intensity exercises may cause lower treatment adherence.

Meditative

[edit]A 2021 meta-analysis found that meditative exercise programs (tai chi, yoga, qigong) were superior to other forms of exercise (aerobic, flexibility, resistance) in improving sleep quality.[141] Other meta-analyses also found positive effects of tai chi for sleep,[157] fibromyalgia symptoms,[158] and pain, fatigue, depression and quality of life.[159] These tai chi interventions frequently included 1-hour sessions practiced 1-3 times a week for 12 weeks. Meditative exercises, as a whole, may achieve desired outcomes through biological mechanisms such as antioxidation, anti-inflammation, reduction in sympathetic activity and modulation of glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity.[137]

Aquatic

[edit]Several reviews and meta-analyses suggest that aquatic training can improve symptoms and wellness in people with fibromyalgia.[160][161][162][163][164][165] It is recommended to practice aquatic therapy at least twice a week using a low to moderate intensity.[164] However, aquatic therapy does not appear to be superior to other types of exercise.[166]

Other

[edit]Limited evidence suggests vibration training in combination with exercise may improve pain, fatigue, and stiffness.[167]

Medications

[edit]A few countries have published guidelines for the management and treatment of fibromyalgia. As of 2018, all of them emphasize that medications are not required. However, medications, though imperfect, continue to be a component of treatment strategy for fibromyalgia patients. The German guidelines outlined parameters for drug therapy termination and recommended considering drug holidays after six months.[19]

Health Canada and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have approved pregabalin[168] (an anticonvulsant) and duloxetine (a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) for the management of fibromyalgia. The FDA also approved milnacipran (another serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), but the European Medicines Agency refused marketing authority.[169]

The medications duloxetine, milnacipran, or pregabalin have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of fibromyalgia.[170]

Antidepressants

[edit]Antidepressants are one of the common drugs for fibromyalgia. A 2021 meta-analysis concluded that antidepressants can improve the quality of life for fibromyalgia patients in the medium term.[20] For most people with fibromyalgia, the potential benefits of treatment with the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and milnacipran and the tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, are outweighed by significant adverse effects (more adverse effects than benefits), however, a small number of people may experience relief from symptoms with these medications.[171][172][173]

The length of time that antidepressant medications take to be effective at reducing symptoms can vary. Any potential benefits from the antidepressant amitriptyline may take up to three months to take effect and it may take between three and six months for duloxetine, milnacipran, and pregabalin to be effective at improving symptoms.[174] Some medications have the potential to cause withdrawal symptoms when stopping so gradual discontinuation may be warranted particularly for antidepressants and pregabalin.[23]

Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

[edit]A 2023 meta-analysis found that duloxetine improved fibromyalgia symptoms, regardless of the dosage.[175] SSRIs may be also be used to treat depression in people diagnosed with fibromyalgia.[176]

Tricyclic antidepressants

[edit]While amitriptyline has been used as a first-line treatment, the quality of evidence to support this use and comparison between different medications is poor.[177][173] Very weak evidence indicates that a very small number of people may benefit from treatment with the tetracyclic antidepressant mirtazapine, however, for most, the potential benefits are not great and the risk of adverse effects and potential harm outweighs any potential for benefit.[178] As of 2018, the only tricyclic antidepressant that has sufficient evidence is amitriptyline.[19][177]

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

[edit]Tentative evidence suggests that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as pirlindole and moclobemide are moderately effective for reducing pain.[179] Very low-quality evidence suggests pirlindole as more effective at treating pain than moclobemide.[179] Side effects of MAOIs may include nausea and vomiting.[179]

Central nervous system depressants

[edit]Central nervous system depressants include drug categories such as sedatives, tranquilizers, and hypnotics. A 2021 meta-analysis concluded that such drugs can improve the quality of life for fibromyalgia patients in the medium term.[20]

Anti-seizure medication

[edit]The anti-convulsant medications gabapentin and pregabalin may be used to reduce pain.[8] There is tentative evidence that gabapentin may be of benefit for pain in about 18% of people with fibromyalgia.[8] It is not possible to predict who will benefit, and a short trial may be recommended to test the effectiveness of this type of medication. Approximately 6/10 people who take gabapentin to treat pain related to fibromyalgia experience unpleasant side effects such as dizziness, abnormal walking, or swelling from fluid accumulation.[180] Pregabalin demonstrates a benefit in about 9% of people.[181] Pregabalin reduced time off work by 0.2 days per week.[182]

Cannabinoids

[edit]Cannabinoids may have some benefits for people with fibromyalgia. However, as of 2022, the data on the topic is still limited.[183][184][185] Cannabinoids may also have adverse effects and may negatively interact with common rheumatological drugs.[186]

Opioids

[edit]The use of opioids is controversial. As of 2015, no opioid is approved for use in this condition by the FDA.[187] A 2016 Cochrane review concluded that there is no good evidence to support or refute the suggestion that oxycodone, alone or in combination with naloxone, reduces pain in fibromyalgia.[188] The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) in 2014 stated that there was a lack of evidence for opioids for most people.[5] The Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany in 2012 made no recommendation either for or against the use of weak opioids because of the limited amount of scientific research addressing their use in the treatment of fibromyalgia. They strongly advise against using strong opioids.[128] The Canadian Pain Society in 2012 said that opioids, starting with a weak opioid like tramadol, can be tried but only for people with moderate to severe pain that is not well-controlled by non-opioid painkillers. They discourage the use of strong opioids and only recommend using them while they continue to provide improved pain and functioning. Healthcare providers should monitor people on opioids for ongoing effectiveness, side effects, and possible unwanted drug behaviors.[130]

A 2015 review found fair evidence to support tramadol use if other medications do not work.[187] A 2018 review found little evidence to support the combination of paracetamol (acetaminophen) and tramadol over a single medication.[189] Goldenberg et al suggest that tramadol works via its serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, rather than via its action as a weak opioid receptor agonist.[190]

A large study of US people with fibromyalgia found that between 2005 and 2007 37.4% were prescribed short-acting opioids and 8.3% were prescribed long-acting opioids,[3] with around 10% of those prescribed short-acting opioids using tramadol;[191] and a 2011 Canadian study of 457 people with fibromyalgia found 32% used opioids and two-thirds of those used strong opioids.[130]

Topical treatment

[edit]Capsaicin has been suggested as a topical pain reliever. Preliminary results suggest that it may improve sleep quality and fatigue, but there are not enough studies to support this claim.[192]

Unapproved or unfounded

[edit]Sodium oxybate increases growth hormone production levels through increased slow-wave sleep patterns. However, this medication was not approved by the FDA for the indication for use in people with fibromyalgia due to the concern for abuse.[193]

The muscle relaxants cyclobenzaprine, carisoprodol with acetaminophen and caffeine, and tizanidine are sometimes used to treat fibromyalgia; however, as of 2015 they are not approved for this use in the United States.[194][195] The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is not recommended as first-line therapy.[196] Moreover, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cannot be considered as useful in the management of fibromyalgia.[197]

Very low-quality evidence suggests quetiapine may be effective in fibromyalgia.[198]

No high-quality evidence exists that suggests synthetic THC (nabilone) helps with fibromyalgia.[199]

Nutrition and dietary supplements

[edit]Nutrition is related to fibromyalgia in several ways. Some nutritional risk factors for fibromyalgia complications are obesity, nutritional deficiencies, food allergies, and consuming food additives.[200] The consumption of fruits and vegetables, low-processed foods, high-quality proteins, and healthy fats may have some benefits.[200] Low-quality evidence found some benefits of a vegetarian or vegan diet.[201]

Although dietary supplements have been widely investigated concerning fibromyalgia, most of the evidence, as of 2021, is of poor quality. It is therefore difficult to reach conclusive recommendations.[202] It appears that Q10 coenzyme and vitamin D supplements can reduce pain and improve quality of life for fibromyalgia patients.[22][203] Q10 coenzyme has beneficial effects on fatigue in fibromyalgia patients, with most studies using doses of 300 mg per day for three months.[204] Q10 coenzyme is hypothesized to improve mitochondrial activity and decrease inflammation.[205] Vitamin D has been shown to improve some fibromyalgia measures, but not others.[203][206]

Two review articles found that melatonin treatment has several positive effects on fibromyalgia patients, including the improvement of sleep quality, pain, and disease impact.[207][208] No major adverse events were reported.[207]

Psychotherapy

[edit]Due to the uncertainty about the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia, current treatment approaches focus on management of symptoms to improve quality of life,[209] using integrated pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches.[4] There is no single intervention shown to be effective for all patients.[210] In a 2020 Cochrane review, cognitive behavioral therapy was found to have a small but beneficial effect for reducing pain and distress but adverse events were not well evaluated.[211] Cognitive behavioral therapy and related psychological and behavioural therapies have a small to moderate effect in reducing symptoms of fibromyalgia.[212][213] Effect sizes tend to be small when cognitive behavioral therapy is used as a stand-alone treatment for patients with fibromyalgia, but these improve significantly when it is part of a wider multidisciplinary treatment program.[213]

A 2010 systematic review of 14 studies reported that cognitive behavioral therapy improves self-efficacy or coping with pain and reduces the number of physician visits at post-treatment, but has no significant effect on pain, fatigue, sleep, or health-related quality of life at post-treatment or follow-up. Depressed mood was also improved but this could not be distinguished from some risks of bias.[214] A 2022 meta-analysis found that cognitive behavioral therapy reduces insomnia in people with chronic pain, including people with fibromyalgia.[215] Acceptance and commitment therapy, a type of cognitive behavioral therapy, has also proven effective.[216]

Patient education

[edit]Patient education is recommended by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) as an important treatment component.[18] As of 2022, there is only low-quality evidence showing that patient education can decrease pain and fibromyalgia impact.[217][218]

Sleep hygiene interventions show low effectiveness in improving insomnia in people with chronic pain.[215]

Physical therapy

[edit]Patients with chronic pain, including those with fibromyalgia, can benefit from techniques such as manual therapy, cryotherapy, and balneotherapy.[219] These can lessen the experience of chronic pain and increase both the amount and quality of sleep. Patients' quality of life is also improved by decreasing pain mechanisms and increasing sleep quality, particularly during the REM phase, sleep efficiency, and alertness.[219]

Manual therapy

[edit]A 2021 meta-analysis concluded that massage and myofascial release diminish pain in the medium term.[20] As of 2015, there was no good evidence for the benefit of other mind-body therapies.[220]

Acupuncture

[edit]A 2013 review found moderate-level evidence on the usage of acupuncture with electrical stimulation for improvement of overall well-being. Acupuncture alone will not have the same effects, but will enhance the influence of exercise and medication in pain and stiffness.[221]

Electrical neuromodulation

[edit]Several forms of electrical neuromodulation, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), have been used to treat fibromyalgia. In general, they help reduce pain and depression and improve functioning.[222][223]

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

[edit]Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is the delivery of pulsed electrical currents to the skin to stimulate peripheral nerves. TENS is widely used to treat pain and is considered to be a low-cost, safe, and self-administered treatment.[224] As such, it is commonly recommended by clinicians to people suffering from pain.[225] On 2019, an overview of eight Cochrane reviews was conducted, covering 51 TENS-related randomized controlled trials.[225] The review concluded that the quality of the available evidence was insufficient to make any recommendations.[225] A later review concluded that transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may diminish pain in the short term, but there was uncertainty about the relevance of the results.[20]

Preliminary findings suggest that electrically stimulating the vagus nerve through an implanted device can potentially reduce fibromyalgia symptoms.[226] However, there may be adverse reactions to the procedure.[226]

Noninvasive brain stimulation

[edit]Noninvasive brain stimulation includes methods such as transcranial direct current stimulation and high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Both methods have been found to improve pain scores in neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.[227]

A 2023 meta-analysis of 16 RCTs found that transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of over 4 weeks can decrease pain in patients with fibromyalgia.[228]

A 2021 meta-analysis of multiple intervention types concluded that magnetic field therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation may diminish pain in the short-term, but conveyed an uncertainty about the relevance of the result.[20] Several 2022 meta-analyses focusing on transcranial magnetic stimulation found positive effects on fibromyalgia.[229][230][231] Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation improved pain in the short-term[230][231] and quality of life after 5–12 weeks.[230][231] Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation did not improve anxiety, depression, and fatigue.[231] Transcranial magnetic stimulation to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex was also ineffective.[230]

EEG neurofeedback

[edit]A systematic review of EEG neurofeedback for the treatment of fibromyalgia found most treatments showed significant improvements of the main symptoms of the disease.[232] However, the protocols were so different, and the lack of controls or randomization impede drawing conclusive results.[232]

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

[edit]Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) has shown beneficial effects in treating chronic pain by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress.[100] However, treating fibromyalgia with hyperbaric oxygen therapy is still controversial, in light of the scarcity of large-scale clinical trials.[137] In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy raises safety concerns due to the oxidative damage that may follow it.[137] An evaluation of nine trials with 288 patients in total found that HBOT was more effective at relieving fibromyalgia patients' pain than the control intervention. In most of the trials, HBOT improved sleep disturbance, multidimensional function, patient satisfaction, and tender spots. 24% of the patients experienced negative outcomes.[233]

Prognosis

[edit]Although in itself fibromyalgia is neither degenerative nor fatal, the chronic pain of fibromyalgia is pervasive and persistent. Most people with fibromyalgia report that their symptoms do not improve over time. However, most patients learn to adapt to the symptoms over time. The German guidelines for patients explain that:

- The symptoms of fibromyalgia are persistent in nearly all patients.

- Total relief of symptoms is seldom achieved.

- The symptoms do not lead to disablement and do not shorten life expectancy.[129]

An 11-year follow-up study on 1,555 patients found that most remained with high levels of self-reported symptoms and distress.[non-primary source needed][234] However, there was a great deal of patient heterogeneity accounting for almost half of the variance. At the final observation, 10% of the patients showed substantial improvement with minimal symptoms. An additional 15% had moderate improvement. This state, though, may be transient, given the fluctuations in symptom severity.[non-primary source needed][234]

A study of 97 adolescents diagnosed with fibromyalgia followed them for eight years.[non-primary source needed] After eight years, the majority of youth still experienced pain and disability in physical, social, and psychological areas. At the last follow-up, all participants reported experiencing one or more fibromyalgia symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and/or sleep problems, with 58% matching the complete ACR 2010 criteria for fibromyalgia. Based on the WPI and SS score cut-points, the remaining 42% exhibited subclinical symptoms. Pain and emotional symptom trajectories, on the other hand, displayed a variety of longitudinal patterns. The study concluded that while most patient's fibromyalgia symptoms endure, the severity of their pain tends to reduce over time.[235]

Baseline depressive symptoms in adolescents appear to predict worse pain at follow-up periods.[236][237]

A meta-analysis based on close to 200,000 fibromyalgia patients found that they were at a higher risk for all-cause mortality. Specific mortality causes that were suggested were accidents, infections and suicide.[238]

Epidemiology

[edit]Fibromyalgia is estimated to affect 1.8% of the population.[239]

Even though more than 90% of fibromyalgia patients are women, only 60% of people with fibromyalgia symptoms are female in the general population.[240]

Society and culture

[edit]Economics

[edit]People with fibromyalgia generally have higher healthcare costs and utilization rates. A review of 36 studies found that fibromyalgia causes a significant economic burden on healthcare systems.[241] Annual costs per patient were estimated to be up to $35,920 in the US and $8,504 in Europe.[241]

Controversies

[edit]Fibromyalgia was defined relatively recently. In the past, it was a disputed diagnosis. Rheumatologist Frederick Wolfe, lead author of the 1990 paper that first defined the diagnostic guidelines for fibromyalgia, stated in 2008 that he believed it "clearly" not to be a disease but instead a physical response to depression and stress.[242] In 2013, Wolfe added that its causes "are controversial in a sense" and "there are many factors that produce these symptoms – some are psychological and some are physical and it does exist on a continuum".[243] Some members of the medical community do not consider fibromyalgia a disease because of a lack of abnormalities on physical examination and the absence of objective diagnostic tests.[29][244]

In the past, some psychiatrists have viewed fibromyalgia as a type of affective disorder, or a somatic symptom disorder. These controversies do not engage healthcare specialists alone; some patients object to fibromyalgia being described in purely somatic terms.[245]

As of 2022, neurologists and pain specialists tend to view fibromyalgia as a pathology due to dysfunction of muscles and connective tissue as well as functional abnormalities in the central nervous system. Rheumatologists define the syndrome in the context of "central sensitization" – heightened brain response to normal stimuli in the absence of disorders of the muscles, joints, or connective tissues. Because of this symptomatic overlap, some researchers have proposed that fibromyalgia and other analogous syndromes be classified together as central sensitivity syndromes.[246][13]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Shoulder girdle (left & right), upper arm (left & right), lower arm (left & right), hip/buttock/trochanter (left & right), upper leg (left & right), lower leg (left & right), jaw (left & right), chest, abdomen, back (upper & lower), and neck.[35]: 607

- ^ Somatic symptoms include, but are not limited to muscle pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue or tiredness, problems thinking or remembering, muscle weakness, headache, pain or cramps in the abdomen, numbness or tingling, dizziness, insomnia, depression, constipation, pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, nervousness, chest pain, blurred vision, fever, diarrhea, dry mouth, itching, wheezing, Raynaud's phenomenon, hives or welts, ringing in the ears, vomiting, heartburn, oral ulcers, loss of or changes in taste, seizures, dry eyes, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, rash, sun sensitivity, hearing difficulties, easy bruising, hair loss, frequent or painful urination, and bladder spasms.[35]: 607

References

[edit]- ^ "fibromyalgia". Collins Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Neurology Now: Fibromyalgia: Is Fibromyalgia Real? | American Academy of Neurology". tools.aan.com. October 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Ngian GS, Guymer EK, Littlejohn GO (February 2011). "The use of opioids in fibromyalgia". International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 14 (1): 6–11. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01567.x. PMID 21303476. S2CID 29000267.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Clauw DJ (April 2014). "Fibromyalgia: a clinical review". JAMA. 311 (15): 1547–1555. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3266. PMID 24737367. S2CID 43693607.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Questions and Answers about Fibromyalgia". NIAMS. July 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Ferri FF (2010). "Chapter F". Ferri's differential diagnosis: a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ Schneider MJ, Brady DM, Perle SM (2006). "Commentary: differential diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome: proposal of a model and algorithm for patients presenting with the primary symptom of chronic widespread pain". Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 29 (6): 493–501. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.06.010. PMID 16904498.

- ^ a b c Cooper TE, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (January 2017). "Gabapentin for fibromyalgia pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD012188. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012188.pub2. PMC 6465053. PMID 28045473.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RL, et al. (December 2016). "2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 46 (3): 319–329. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012. PMID 27916278.

- ^ a b Wu YL, Chang LY, Lee HC, Fang SC, Tsai PS (May 2017). "Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia: A meta-analysis of case-control studies". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 96: 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.03.011. PMID 28545798.

- ^ a b c d e f g Häuser W, Sarzi-Puttini P, Fitzcharles MA (2019). "Fibromyalgia syndrome: under-, over- and misdiagnosis". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 37 (1 Suppl 116): 90–97. PMID 30747096.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Arnold LM, Bennett RM, Crofford LJ, Dean LE, Clauw DJ, Goldenberg DL, et al. (June 2019). "AAPT Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia". The Journal of Pain. 20 (6): 611–628. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.10.008. hdl:2434/632765. PMID 30453109. S2CID 53872511.

- ^ a b c Mezhov V, Guymer E, Littlejohn G (December 2021). "Central sensitivity and fibromyalgia". Internal Medicine Journal. 51 (12): 1990–1998. doi:10.1111/imj.15430. PMID 34139045. S2CID 235471910.

- ^ a b Galvez-Sánchez CM, Reyes Del Paso GA (April 2020). "Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia: Critical Review and Future Perspectives". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (4): 1219. doi:10.3390/jcm9041219. PMC 7230253. PMID 32340369.

Furthermore, in many cases the FMS diagnosis is fundamentally based on the exclusion of other similar diseases; in spite of that practice not being recommended because of its lack of precision and the high possibility of misdiagnosis.

- ^ Bergmann U (2012). Neurobiological foundations for EMDR practice. New York: Springer Pub. Co. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8261-0938-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, Littlejohn G, Usui C, Häuser W (May 2021). "Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions". Lancet. 397 (10289): 2098–2110. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00392-5. PMID 34062144. S2CID 235245552.

- ^ a b c Prabhakar A, Kaiser JM, Novitch MB, Cornett EM, Urman RD, Kaye AD (March 2019). "The Role of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments in Fibromyalgia: a Comprehensive Review". Current Rheumatology Reports. 21 (5): 14. doi:10.1007/s11926-019-0814-0. PMID 30830504. S2CID 73482737.

- ^ a b c d e f Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Atzeni F, Häuser W, Choy EH, Amris K, et al. (December 2017). "EULAR recommendations for management of fibromyalgia" (PDF). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 76 (12): e54. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211587. PMID 28476880. S2CID 26251476. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Häuser W, Fitzcharles MA (March 2018). "Facts and myths pertaining to fibromyalgia". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 20 (1): 53–62. doi:10.31887/dcns.2018.20.1/whauser. PMC 6016048. PMID 29946212.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mascarenhas RO, Souza MB, Oliveira MX, Lacerda AC, Mendonça VA, Henschke N, Oliveira VC (January 2021). "Association of Therapies With Reduced Pain and Improved Quality of Life in Patients With Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 181 (1): 104–112. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5651. PMC 7589080. PMID 33104162.

- ^ Kia S, Choy E (May 2017). "Update on Treatment Guideline in Fibromyalgia Syndrome with Focus on Pharmacology". Biomedicines. 5 (2): 20. doi:10.3390/biomedicines5020020. PMC 5489806. PMID 28536363.

- ^ a b c Ibáñez-Vera AJ, Alvero-Cruz JR, García-Romero JC (2018). "Therapeutic physical exercise and supplements to treat fibromyalgia". Apunts. Medicina de l'Esport. 53 (197): 33–41. doi:10.1016/j.apunts.2017.07.001.

- ^ a b c Häuser W, Eich W, Herrmann M, Nutzinger DO, Schiltenwolf M, Henningsen P (June 2009). "Fibromyalgia syndrome: classification, diagnosis, and treatment". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 106 (23): 383–391. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0383. PMC 2712241. PMID 19623319.

- ^ Health Information Team (February 2004). "Fibromyalgia". BUPA insurance. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ Yunus M, Masi AT, Calabro JJ, Miller KA, Feigenbaum SL (August 1981). "Primary fibromyalgia (fibrositis): clinical study of 50 patients with matched normal controls". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 11 (1): 151–171. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(81)90096-2. PMID 6944796.

- ^ "Fibro-". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ "Meaning of myo". 12 April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "Meaning of algos". 12 April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ a b Wolfe F (April 2009). "Fibromyalgia wars". The Journal of Rheumatology. 36 (4): 671–678. doi:10.3899/jrheum.081180. PMID 19342721. S2CID 2091976.

- ^ Smythe HA, Moldofsky H (1977). "Two contributions to understanding of the "fibrositis" syndrome". Bulletin on the Rheumatic Diseases. 28 (1): 928–931. PMID 199304.

- ^ Winfield JB (June 2007). "Fibromyalgia and related central sensitivity syndromes: twenty-five years of progress". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 36 (6): 335–338. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.001. PMID 17303220.

- ^ a b Inanici F, Yunus MB (October 2004). "History of fibromyalgia: past to present". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 8 (5): 369–378. doi:10.1007/s11916-996-0010-6. PMID 15361321. S2CID 42573740.

- ^ Goldenberg DL (May 1987). "Fibromyalgia syndrome. An emerging but controversial condition". JAMA. 257 (20): 2782–2787. doi:10.1001/jama.257.20.2782. PMID 3553636.

- ^ Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. (February 1990). "The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 33 (2): 160–172. doi:10.1002/art.1780330203. PMID 2306288.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. (May 2010). "The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity". Arthritis Care & Research. 62 (5): 600–610. doi:10.1002/acr.20140. hdl:2027.42/75772. PMID 20461783. S2CID 17154205.

- ^ a b Clauw DJ, Arnold LM, McCarberg BH (September 2011). "The science of fibromyalgia". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 86 (9): 907–911. doi:10.4065/mcp.2011.0206. PMC 3258006. PMID 21878603.

- ^ "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ Gianlorenço AC, Costa V, Fabris-Moraes W, Menacho M, Alves LG, Martinez-Magallanes D, Fregni F (15 May 2024). "Cluster analysis in fibromyalgia: a systematic review". Rheumatology International. doi:10.1007/s00296-024-05616-2. ISSN 1437-160X. PMID 38748219.

- ^ Besiroglu MD, Dursun MD (July 2019). "The association between fibromyalgia and female sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". International Journal of Impotence Research. 31 (4): 288–297. doi:10.1038/s41443-018-0098-3. PMID 30467351. S2CID 53717513.

- ^ Zdebik N, Zdebik A, Bogusławska J, Przeździecka-Dołyk J, Turno-Kręcicka A (January 2021). "Fibromyalgia syndrome and the eye – A review". Survey of Ophthalmology. 66 (1): 132–137. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2020.05.006. PMID 32512032. S2CID 219548664.

- ^ "Archived copy". academic.oup.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Fibromyalgia – Symptoms". nhs.uk. 20 October 2017. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Fibromyalgia - Symptoms". nhs.uk. 20 October 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Kimura S, Toyoura M, Toyota Y, Takaoka Y (December 2020). "Serum concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-1 as a biomarker of improved circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorder in school-aged children". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 16 (12): 2073–2078. doi:10.5664/jcsm.8778. PMC 7848940. PMID 32876042.

- ^ Spaeth M, Rizzi M, Sarzi-Puttini P (April 2011). "Fibromyalgia and sleep". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 25 (2): 227–239. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.03.004. PMID 22094198.

- ^ a b Bradley LA (December 2009). "Pathophysiology of fibromyalgia". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (12 Suppl): S22 – S30. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.008. PMC 2821819. PMID 19962493.

- ^ Wolfe F, Rasker JJ, Ten Klooster P, Häuser W (December 2021). "Subjective Cognitive Dysfunction in Patients With and Without Fibromyalgia: Prevalence, Predictors, Correlates, and Consequences". Cureus. 13 (12): e20351. doi:10.7759/cureus.20351. PMC 8752385. PMID 35036191.

- ^ a b c Bell T, Trost Z, Buelow MT, Clay O, Younger J, Moore D, Crowe M (September 2018). "Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in fibromyalgia". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 40 (7): 698–714. doi:10.1080/13803395.2017.1422699. PMC 6151134. PMID 29388512.

- ^ Berwick RJ, Siew S, Andersson DA, Marshall A, Goebel A (May 2021). "A Systematic Review Into the Influence of Temperature on Fibromyalgia Pain: Meteorological Studies and Quantitative Sensory Testing". The Journal of Pain. 22 (5): 473–486. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2020.12.005. PMID 33421589. S2CID 231437516.

- ^ Staud R, Godfrey MM, Robinson ME (August 2021). "Fibromyalgia Patients Are Not Only Hypersensitive to Painful Stimuli But Also to Acoustic Stimuli". The Journal of Pain. 22 (8): 914–925. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2021.02.009. PMID 33636370. S2CID 232066286.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kleykamp BA, Ferguson MC, McNicol E, Bixho I, Arnold LM, Edwards RR, et al. (February 2021). "The Prevalence of Psychiatric and Chronic Pain Comorbidities in Fibromyalgia: an ACTTION systematic review". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 51 (1): 166–174. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.10.006. PMID 33383293. S2CID 229948862.

- ^ Habibi Asgarabad M, Salehi Yegaei P, Jafari F, Azami-Aghdash S, Lumley MA (March 2023). "The relationship of alexithymia to pain and other symptoms in fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis". European Journal of Pain. 27 (3): 321–337. doi:10.1002/ejp.2064. PMID 36471652. S2CID 254273680.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fitzcharles MA, Perrot S, Häuser W (October 2018). "Comorbid fibromyalgia: A qualitative review of prevalence and importance". European Journal of Pain. 22 (9): 1565–1576. doi:10.1002/ejp.1252. PMID 29802812. S2CID 44068037.

- ^ Yepez D, Grandes XA, Talanki Manjunatha R, Habib S, Sangaraju SL (May 2022). "Fibromyalgia and Depression: A Literature Review of Their Shared Aspects". Cureus. 14 (5): e24909. doi:10.7759/cureus.24909. PMC 9187156. PMID 35698706.

- ^ Løge-Hagen JS, Sæle A, Juhl C, Bech P, Stenager E, Mellentin AI (February 2019). "Prevalence of depressive disorder among patients with fibromyalgia: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Affective Disorders. 245: 1098–1105. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.001. PMID 30699852. S2CID 73411416.

- ^ Bruce DF, PhD. "Fibromyalgia and Depression". WebMD. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ a b Ramírez-Morales R, Bermúdez-Benítez E, Martínez-Martínez LA, Martínez-Lavín M (August 2022). "Clinical overlap between fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis. A systematic review and meta-analysis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 21 (8): 103129. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2022.103129. PMID 35690247.

- ^ a b Goldenberg DL (2024). "How to understand the overlap of long COVID, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis, fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndromes". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 67: 152455. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2024.152455. PMID 38761526.

- ^ Anderson G, Maes M (December 2020). "Mitochondria and immunity in chronic fatigue syndrome". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 103: 109976. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109976. PMID 32470498. S2CID 219104988.

- ^ Valencia C, Fatima H, Nwankwo I, Anam M, Maharjan S, Amjad Z, et al. (October 2022). "A Correlation Between the Pathogenic Processes of Fibromyalgia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the Middle-Aged Population: A Systematic Review". Cureus. 14 (10): e29923. doi:10.7759/cureus.29923. PMC 9635936. PMID 36381861.

- ^ D'Onghia M, Ciaffi J, Lisi L, Mancarella L, Ricci S, Stefanelli N, et al. (April 2021). "Fibromyalgia and obesity: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 51 (2): 409–424. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.02.007. PMID 33676126. S2CID 232136088.

- ^ Alsiri N, Alhadhoud M, Alkatefi T, Palmer S (February 2023). "The concomitant diagnosis of fibromyalgia and connective tissue disorders: A systematic review" (PDF). Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 58: 152127. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2022.152127. PMID 36462303. S2CID 253650110. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Kocyigit BF, Akyol A (March 2023). "Coexistence of fibromyalgia syndrome and inflammatory rheumatic diseases, and autonomic cardiovascular system involvement in fibromyalgia syndrome". Clinical Rheumatology. 42 (3): 645–652. doi:10.1007/s10067-022-06385-8. PMID 36151442. S2CID 252496799.

- ^ He J (2024). "Fibromyalgia in Obstructive Sleep Apnea-hypopnea Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Frontiers in Physiology. 15. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1394865. PMC 11144865. PMID 38831795.

- ^ Padhan P, Maikap D, Pathak M (2023). "Restless leg syndrome in rheumatic conditions: Its prevalence and risk factors, a meta-analysis". International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 26 (6): 1111–1119. doi:10.1111/1756-185X.14710. ISSN 1756-1841. PMID 37137528. S2CID 258484602. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Goldberg N, Tamam S, Weintraub AY (December 2022). "The association between overactive bladder and fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 159 (3): 630–641. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14290. PMID 35641437. S2CID 249236213.

- ^ Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Mease PJ (April 2011). "Chronic widespread pain: from peripheral to central evolution". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 25 (2): 133–139. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.04.001. ISSN 1532-1770. PMID 22094190.

- ^ Schmidt-Wilcke T, Clauw DJ (19 July 2011). "Fibromyalgia: from pathophysiology to therapy". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 7 (9): 518–527. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2011.98. ISSN 1759-4804. PMID 21769128.

- ^ a b c d e D'Agnelli S, Arendt-Nielsen L, Gerra MC, Zatorri K, Boggiani L, Baciarello M, Bignami E (January 2019). "Fibromyalgia: Genetics and epigenetics insights may provide the basis for the development of diagnostic biomarkers". Molecular Pain. 15: 1744806918819944. doi:10.1177/1744806918819944. PMC 6322092. PMID 30486733.

- ^ a b c Ablin JN, Buskila D (February 2015). "Update on the genetics of the fibromyalgia syndrome". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 29 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.018. PMID 26266996.

- ^ Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG (February 2012). "Candidate gene studies of fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Rheumatology International. 32 (2): 417–426. doi:10.1007/s00296-010-1678-9. PMID 21120487. S2CID 6239018.

- ^ Dutta D, Brummett CM, Moser SE, Fritsche LG, Tsodikov A, Lee S, et al. (May 2020). "Heritability of the Fibromyalgia Phenotype Varies by Age". Arthritis & Rheumatology. 72 (5): 815–823. doi:10.1002/art.41171. PMC 8372844. PMID 31736264.