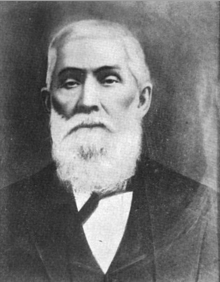

William P. Ross

William P. Ross | |

|---|---|

| |

| Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation | |

| In office 1866–1867 | |

| Preceded by | John Ross |

| Succeeded by | Lewis Downing |

| In office 1872–1875 | |

| Preceded by | Lewis Downing |

| Succeeded by | Charles Thompson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Potter Ross August 28, 1820 Lookout Mountain, Tennessee |

| Died | July 20, 1891 (aged 70) Fort Gibson, Oklahoma |

| Nationality | Cherokee |

| Spouse | Mary Jane Ross |

| Occupation | Lawyer, merchant, politician |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States |

| Branch | Confederate States Army |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Unit | 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles |

| Battles | |

William Potter Ross (August 28, 1820 – July 20, 1891), also known as Will Ross, was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation 1866-1867 and 1872-1875. Born to a Scottish father and a mixed-blood Cherokee mother (the sister of future chief John Ross), he was raised in a bilingual home. Ross attended English-speaking schools. He attended Princeton University, where he graduated first in his class in 1844.

Ross served in several different roles in the Cherokee Nation. By then, his uncle had been elected as principal chief. Ross became clerk of the Cherokee Senate in 1843. He became the founder and editor of the Cherokee Advocate. Later, he was appointed director of the Cherokee Male and Female seminaries, then served as Treasurer of the Cherokee Nation.

Ross was chosen to lead the Nation by the National Council on October 19, 1866, and served for several months until the election in 1867. He was later elected to succeed Lewis Downing, and served from 1872 to 1875. After his term ended, Ross retired to Fort Gibson, where he became a merchant and practiced law. He died there on July 20, 1891.

Lineage

[edit]Ross was the son of John Golden Ross (no blood relation to Chief John Ross), who was born in Scotland December 23, 1787. Little more is known of his parents, except that they emigrated to North America with Will and his sister while the children were very young. The father was swept overboard during a violent storm, and his mother died before the ship reached land. The ship's captain gave the children to a couple in Baltimore who gave them a home. The sister died shortly, but young John grew up in Baltimore, where he attended school and became a cabinetmaker.[1]

John Golden Ross left Baltimore (possibly about the time of the War of 1812), and went to Tennessee by himself. He enlisted in the Tennessee militia and fought in the Creek War under Andrew Jackson. He returned to Tennessee, where he married Eliza Ross. Eliza was part Cherokee, the daughter of Daniel and Mary Ross and sister of the mother of John Ross, who would later achieve fame as Principal Chief of the Cherokees. Eliza had been born near Lookout Mountain on March 25, 1789. The marriage made John G. a member of the Cherokee tribe. He and Eliza settled near Lookout Mountain, where they welcomed their first child, Will, on August 20, 1820.[1]

Education

[edit]Eliza began teaching young Will to read at home. The parents were bilingual, so Will learned early to communicate in both English and Cherokee. Later, he attended the Presbyterian Mission School at Will's Valley, Alabama. Then he went to an academy at Granville, Tennessee. When he was seventeen, he went to Hamill's Preparatory School at Lawrenceville, New Jersey. Will's uncle John sent him to Princeton, where he graduated in 1842, scholastically first in his class of 44 men.[1]

In the fall and winter of 1842–43, Will taught school held in a Methodist church near the present town of Hulbert, Oklahoma. His Uncle John helped him to become clerk of the Cherokee Senate in 1843, where he helped write legislation and drafted papers for his uncle. During the session, the Council established the weekly newspaper Cherokee Advocate and named Will as editor. He continued in this position for four years. Retiring from the paper, he worked as a merchant and practiced law. In 1849, he was elected to the Cherokee Senate, where he served four two-year terms. He left the Senate to become secretary to another uncle, Lewis Ross, who was then Treasurer of the Cherokee Nation.[1]

Will's uncle John sent him to Princeton then helped him to gain experience in several tribal positions. In particular, Will edited the Cherokee Advocate, was the director of the Cherokee seminaries, and served as national treasurer. He was a colonel in the home guard during the Civil War. He had been a member of the Cherokee Council and had participated many times as a member of delegations to Washington D. C. negotiating treaties with the Federal Government. He also was a lawyer, trader, sawmill owner, farmer, and businessman. He was very loyal to his uncle and strongly favored his uncle's policies. Otherwise, he had little in common with the full-bloods who were the core of the "Loyal party".[2]

American Civil War

[edit]The tribe was bitterly divided over the American Civil War. Immediately after war broke out between the Union and the Confederacy, many leading Cherokees wanted their tribe to remain neutral. One faction, led by Chief John Ross, believed that the tribe would fare best by remaining loyal to the Union. This group, known as the "Loyal Party," was composed largely of full-blood Cherokees who were not slave owners. But when the Union abandoned its forts in Indian Territory and Confederate troops moved in, neutrality was no longer an option. The council agreed to a treaty with the Confederate States of America, which Chief Ross signed. Will Ross enlisted in the Confederate Army as lieutenant colonel in the 1st Cherokee Regiment of Mounted Rifles.[3] He participated in the battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas in 1862.

The council elected Will as Principal Chief because they believed he had more experience and knowledge in the ways of government than did Downing. Moreover, Downing could not speak or read English, which would be a disadvantage in negotiations. The first act under Will's chieftainship was to amend the constitution and laws of the Cherokee Nation. First, the Council deleted all references to the institution of slavery. The second amendment gave citizenship, voting rights and the right to hold public office to all former Cherokee slaves that returned to live in the nation's boundaries by January 17, 1867. There was almost no opposition to these amendments because the "Southern Cherokees", who had followed Stand Watie and Elias C. Boudinot had previously fled the nation's boundaries and had boycotted the Council meetings. Thus, by popular vote on November 26, 1866, the Cherokee people approved the amendments.[4]

The Southern Cherokees, as they were now known, held their own convention on December 31, 1866. They voted to send their own delegation to Washington. The new Secretary of the Interior, Orville H. Browning, accepted the members as legitimate delegates and held official meetings with them.[5]

Despite his capabilities as principal chief, Ross could not bridge the gap between the Loyals and the Southerners to heal the wound. Ross hated the leaders of the Southern group, and they returned those feelings for him. He refused to allow the southerners any political influence, and even some of his friends felt he lacked the traditional spirit of tribal harmony.[6] Stand Watie, in particular, remained in exile in Texas, where he had sent his family for safety. Ross refused to change his views, which led to an insurgency within his own party. It resulted in the close election of Lewis Downing to replace Ross as chief in August 1867. After losing the election, Ross retired to private life at Fort Gibson, where he became a merchant and practiced law.[7]

Return to Cherokee leadership

[edit]When Lewis Downing died of pneumonia, barely two weeks into his second term as Principal Chief, the council called on Will Ross to complete Downing's term. It would be fraught with difficulties. The Southern party did not support him. The full-bloods feared that they would lose the political advantage that Downing had helped them secure. They did not want the Cherokee Nation to be dominated by the English-speaking, wealthy mixed bloods. Externally, whites continued their political pressure to open Indian Territory for settlement and development by white people. Congress kept intruding into the decisions of who could qualify as a Cherokee citizen. Many of his fellow tribesmen blamed Ross for allowing an increase in all sorts of crimes, even though crime had increased all across the United States.[8]

Later years and death

[edit]Will married his second wife, Mary Jane Ross, at Park Hill on November 16, 1846. She was born the daughter of Lewis Ross on November 5, 1827.[1]

Ross died at Fort Gibson on July 20, 1891. He was buried at Citizens Cemetery there. His wife, Mary Jane lived until July 29, 1908, when she also died and was buried in Fort Gibson.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Meserve, John Bartlett."Chief William Potter Ross." Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 15, No. 1, March 1937. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ McLoughlin, p. 229

- ^ William L. Anderson, "Ross, William Potter (1820–1891)" Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- ^ McLoughlin, p. 230.

- ^ McLoughlin, p. 231.

- ^ McLoughlin, p.246.

- ^ McLoughlin, p. 246–8.

- ^ McLoughlin, p. 288–290.

- Cherokee.org

- "Cherokee History", Discoverkingsport.com

Sources

[edit]McLoughlin, William G. After the Trail of Tears: The Cherokees' Struggle for Sovereignty 1839-1880. 1993. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill. ISBN 0-8078-2111-X

External links

[edit]

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch