Year of the Four Emperors

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2020) |

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Year of the Four Emperors | ||

| Chronology | ||

| Succession | ||

| ||

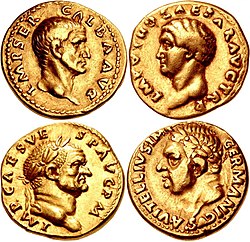

The Year of the Four Emperors, AD 69, was the first civil war of the Roman Empire, during which four emperors ruled in succession: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian.[1] It is considered an important interval, marking the transition from the Julio-Claudians, the first imperial dynasty, to the Flavian dynasty. The period witnessed several rebellions and claimants, with shifting allegiances and widespread turmoil in Rome and the provinces.

In 68, Vindex, legate of Gallia Lugdunensis, revolted against Nero and encouraged Galba, governor of Hispania, to claim the Empire. The latter was proclaimed emperor by his legion in early April. He was notably supported by Otho, legate of Lusitania. Soon after, the legate of a legion in Africa, Clodius Macer, also rebelled against Nero. Vindex was defeated by the Rhine legions at the Battle of Vesontio, but they too rebelled against Nero. Finally, on 9 June 68, Nero took his own life after being declared a public enemy by the Senate, which made Galba the new emperor. However, Galba was unable to establish his authority over the Empire, as several of his supporters were disappointed by his lack of gratitude. He especially adopted Piso Licinianus as heir (Galba was childless and elderly), instead of Otho, who, it had widely been assumed, would be chosen. Angered by this disgrace, Otho murdered Galba on 15 January with the help of the Praetorian Guard, and became emperor instead. Unlike Galba, he rapidly earned considerable popularity, notably by bestowing favours and emulating Nero's successful early years.

Otho still had to face another claimant, Vitellius, who had been acclaimed by the legions of the Rhine on 1 January 69. Vitellius won the First Battle of Bedriacum on 14 April, defeating the emperor. Otho took his own life the next day, and Vitellius was appointed emperor by the Senate on 19 April. The new emperor had little support outside of his veterans from the German legions, though. When Vespasian, legate of Syria, made his bid known, he received the allegiance of the legions of the Danube as well as many former supporters of Galba and Otho. After his acclamation in Alexandria on 1 July, Vespasian sent his friend Mucianus with a part of his army to fight Vitellius, but the Danubian legions commanded by Antonius Primus had not waited for Mucianus and defeated Vitellius' legions at the Second Battle of Bedriacum on 24 October. Vitellius was subsequently killed by a mob on 20 December. Mucianus arrived several days after and swiftly secured Vespasian's position in Rome (Primus had acted independently from him).

The death of Vitellius did not end the civil war, as the Rhine legions still rejected the rule of Vespasian and the new Flavian dynasty. Some Batavi provincials led by Civilis had fought them since Vitellius' acclamation. In 70, the new regime finally won the legions' surrender after negotiations, mainly because they lacked an alternative to Vespasian. Later, the new regime distorted the events—especially through the writings of the historian Tacitus—in order to remove the embarrassment of having relied on the Batavi to fight Roman legions. The Batavi were therefore said to have revolted against Rome, and the events dubbed the Revolt of the Batavi.[2]

History

[edit]Vindex's revolt and fall of Nero (March–June 68)

[edit]

The end of Nero's reign (54–68) was marked by political trials and plots, such as the Pisonian conspiracy in 65, showing the disenchantment of the senatorial elite towards the Emperor.[3] In the winter of 67–68, Gaius Julius Vindex, the legate of Gallia Lugdunensis, looked for support among other governors and administrators in order to start a revolt against Nero. Aware of his relatively humble origins, Vindex did not covet the Empire for himself, nor did he name a candidate, probably to maximise his chances of finding someone interested. Plutarch tells that the people reached by Vindex forwarded his letters to Nero, except one: his southern neighbour Servius Sulpicius Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, the largest Spanish province.[4] In mid-March 68, Vindex proceeded with his plan and raised an army composed of Gallic tribesmen, which nevertheless cut short his attempts to win over the officers of the seven legions posted on the Rhine, whose soldiers would not accept fighting alongside Gauls. As a result, Vindex turned towards Galba, the only man who had not denounced him to Nero.[5]

In early April 68, Galba accepted Vindex's proposition and was acclaimed emperor in Carthago Nova (now Cartagena, Spain). He rapidly received support from officials of Baetica and Lusitania, the other two Iberian provinces, who provided him with the money to raise the VII Galbiana, a second legion, in addition to the VI Victrix based in Galba's province.[6]

Meanwhile, Vindex had to besiege his own former capital, Lugdunum, as its citizens were particularly devoted to Nero, which led Lucius Verginius Rufus, the governor of Germania Superior, to march on Vindex. He besieged Vesontio, capital of the Sequani, a tribe that supported Vindex, who therefore had to leave the siege of Lugdunum to come to their aid. Before Vesontio, Verginius and Vindex had a talk, during which they agreed to unite their forces against Nero. However, Verginius' legions ignored the agreement and charged the unprepared troops of Vindex, of whom up to 20,000 died, while Vindex committed suicide. Soon after, the Rhine legions proclaimed Verginius emperor, but he refused to accept.[7] The soldiers were motivated by their hatred of Galba, as they had not forgotten his term as governor of Germania Superior in 39–41, during which he harshly repressed the legions that had supported the rebellion of Lentulus Gaetilicus in 39.[8]

In Rome, Nero was unable to organise resistance to Galba's claim and was even thinking about fleeing to Egypt. The decisive move came from Nymphidius Sabinus, deputy prefect of the Praetorian Guard, who convinced his men to abandon Nero, by promising that Galba would give each of them 30,000 sesterces (equivalent to 10 years of wages), while he expected to be rewarded by the new emperor.[9] On 9 June 68, the Senate declared Nero enemy of the state and proclaimed Galba emperor, which prompted Nero's suicide.[10]

Galba

[edit]

Galba was still in Spain when he received the news he had become emperor. He took at least a month to secure the Spanish provinces before leaving. He appointed Cluvius Rufus as his replacement in his own province, but also murdered several of his opponents there, including Obultronius Sabinus, the probable governor of Baetica.[11] Escorted by the VII Galbiana, he left for Rome along the coastline, stopping at Narbo Martius. In Gaul, Galba executed Betuus Cilo, who as governor of Aquitania had fought Vindex. He also relieved Verginius Rufus from his post in Germania Superior because his acclamation by the legions could make him a dangerous rival.[12] Meanwhile, in Rome, Nymphidius Sabinus realised that Galba had no intention of rewarding him with the post of praetorian prefect he coveted. He then pretended to be an illegitimate son of Caligula and started to conspire against Galba to make himself emperor. However, he was murdered by the Praetorian Guards when he tried to read before them a speech announcing his bid for the Empire.[13]

During the first half of October, Galba finally completed his journey to Rome, which was described by Tacitus as "a long and bloody march",[14] because of the officials he had murdered on his way and also for the massacre he committed on the Milvian Bridge, just before the city. In order to fight Galba, Nero had created the legion I Adiutrix from sailors of the Roman navy; when Galba arrived at Rome, the new legionaries pressed Galba to confirm their status, but he ordered his troops to charge them, killing thousands.[15] He then accepted their request, but after they submitted to a decimation, a practice not used since Tiberius, which severely lowered the troops' morale.[16] Galba also refused to pay the Praetorians the money promised by Nymphidius for overthrowing Nero.[17]

Galba continued the practice set by Nero of appointing ineffectual men to the most important posts in the provinces: for example, he sent the old and disabled Hordeonius Flaccus to Germania Superior and Aulus Vitellius to Germania Inferior; the latter being mostly known at the time as a penniless glutton.[18] In Rome, Galba considered with contempt anybody who had served under Nero. He only trusted three men who had been with him in Spain: Titus Vinius, Cornelius Laco, and Icelus, who had amassed money as Nero's protegés had, which likewise triggered popular resentment against the new emperor.[19] Galba even turned against his first supporters, among them Aulus Caecina Alienus, former quaestor of Baetica, who had sent the money in his possession when Galba rebelled. The emperor had given him command of IV Macedonica in Germania Superior but recalled him for embezzlement soon after.[20]

Moreover, at the beginning of the civil year of 69 on 1 January, the legions of Germania Inferior refused to swear allegiance and obedience to Galba. On the following day, the legions acclaimed their governor Vitellius as emperor. Hearing the news of the loss of the Rhine legions, Galba panicked. He adopted a young senator, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus, as his successor. By doing so he offended many, above all Marcus Salvius Otho, an influential and ambitious nobleman who desired the honour for himself. Otho bribed the Praetorian Guard, already very unhappy with the emperor. When Galba heard about the coup d'état, he went to the streets in an attempt to stabilize the situation. It proved a mistake because he could not attract any supporters. Shortly afterwards the Praetorian Guard killed him in the Forum, along with Lucius and impaled their heads on poles.[21]

Otho

[edit]

On the day of Galba's murder, the Senate recognized Otho as emperor.[22] They saluted the new emperor with relief. Although ambitious and greedy, Otho did not have a record of tyranny or cruelty and was expected to be a fair emperor. However, Otho's initial efforts to restore peace and stability were soon checked by the revelation that Vitellius had declared himself Imperator in Germania and had dispatched half of his army to march on Italy.

Backing Vitellius were the finest legions of the Empire, composed of veterans of the Germanic Wars, such as I Germanica and XXI Rapax. These would prove to be the best arguments for his bid for power. Otho was not keen to begin another civil war and sent emissaries to propose a peace and convey his offer to marry Vitellius's daughter. It was too late to reason; Vitellius's generals were leading half of his army toward Italy. After a series of minor victories, Otho suffered defeat in the First Battle of Bedriacum. Rather than flee and attempt a counter-attack, Otho decided to put an end to the anarchy and committed suicide. He had been emperor for a little more than three months.

Vitellius

[edit]

On the news of Otho's suicide, the Senate recognized Vitellius as emperor. With this recognition, Vitellius set out for Rome; however, he faced problems from the start of his reign. The city remained very sceptical when Vitellius chose the anniversary of the Battle of the Allia (in 390 BC), a day of bad auspices according to Roman superstition, to accede to the office of Pontifex Maximus.

Events seemed to prove the omens right. With the throne tightly secured, Vitellius engaged in a series of banquets (Suetonius refers to three a day: morning, afternoon, and night) and triumphal parades that drove the imperial treasury close to bankruptcy. Debts quickly accrued, and moneylenders started to demand repayment. Vitellius showed his violent nature by ordering the torture and execution of those who dared to make such demands. With financial affairs in a state of calamity, Vitellius took to killing citizens who had named him as their heir, often together with any co-heirs. Moreover, he sought to rid himself of every possible rival, inviting them to the palace with promises of power, only to order their hasty assassination.

Vespasian

[edit]

Meanwhile, the legions stationed in the African province of Egypt and the Middle Eastern provinces of Iudaea (Judea) and Syria acclaimed Vespasian as emperor. Vespasian had received a special command in Judaea from Nero in AD 67, with the task of putting down the First Jewish–Roman War. He gained the support of the governor of Syria, Gaius Licinius Mucianus. A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus. Vespasian himself travelled to Alexandria, where he was acclaimed emperor on 1 July, thereby gaining control of the vital grain supplies from Egypt. His son Titus remained in Judaea to deal with the Jewish rebellion. Before the eastern legions could reach Rome, the Danubian legions of the provinces of Raetia and Moesia also acclaimed Vespasian as emperor in August, and, led by Marcus Antonius Primus, invaded Italy. In October, the forces led by Primus won a crushing victory over Vitellius's army at the Second Battle of Bedriacum.

Surrounded by enemies, Vitellius made a last attempt to win the city to his side, distributing bribes and promises of power where needed. He tried to levy several allied tribes, such as the Batavians, by force, but they refused. The Danube army was now very near Rome. Realizing the immediate threat, Vitellius made a last attempt to gain time by sending emissaries, accompanied by Vestal Virgins, to negotiate a truce and start peace talks. The following day, messengers arrived with news that the enemy was at the gates of the city. Vitellius went into hiding and prepared to flee, but decided on one last visit to the palace, where Vespasian's men caught and killed him. In seizing the capital, they burned down the temple of Jupiter.

The Senate acknowledged Vespasian as emperor the following day, 21 December 69.

Vespasian faced no direct threat to his imperial power after the death of Vitellius. He became the founder of the stable Flavian dynasty, which succeeded the Julio-Claudians. He died of natural causes in 79. The Flavians, each in turn, ruled from AD 69 to AD 96.

Chronology

[edit]68

[edit]- April – Galba, governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, and Vindex, governor of Gallia Lugdunensis rebel against Nero

- May – The Rhine legions defeat and kill Vindex in Gaul

- June – Nero is declared a public enemy (hostis) by the Senate (8 June) and commits suicide (9 June); Galba is recognised emperor

- November – Vitellius nominated governor of Germania Inferior

69

[edit]- 1 January – The Rhine legions refuse to swear loyalty to Galba

- 2 January – Vitellius acclaimed emperor by the Rhine

- 15 January – Galba killed by the Praetorian Guard; in the same day, the Senate recognizes Otho as emperor

- 14 April – Vitellius defeats Otho

- 16 April – Otho commits suicide; Vitellius recognised emperor

- 1 July – Vespasian, commander of the Roman army in Judaea, proclaimed emperor by the legions of Egypt under Tiberius Julius Alexander

- August – The Danubian legions announce support to Vespasian (in Syria) and invade Italy in September on his behalf

- October – The Danubian army defeats Vitellius and Vespasian occupies Egypt

- 20 December – Vitellius killed by soldiers in the Imperial Palace

- 21 December – Vespasian recognized emperor

Sources

[edit]The most detailed historical sources about the events of 69 AD are:

- The Annals and the Histories of Tacitus;

- The Twelve Caesars of Suetonius;

- The Roman History of Cassius Dio;

- The Life of Galba, the Life of Otho and fragments of the Life of Nero by Plutarch;

Other sources on the Year of the Four Emperors are The Jewish War and the Antiquities of the Jews of Josephus; while mainly focusing on the events of Palestine, these works also mention the revolts in Rome.

See also

[edit]- Tacitus, Histories

- Year of the Five Emperors (AD 193)

- Year of the Six Emperors (AD 238)

References

[edit]- ^ Martin, Ronald H. (1981). Tacitus. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-520-04427-2.

- ^ Wiedemann 2010, pp. 280–282

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 17–18

- ^ Plutarch. Life of Galba. 4.

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 19–20

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 21–22

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 22–24, calls Verginius a "mediocrity", for whom the Empire was out of his depth.

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 25–27

- ^ Morgan 2006, p. 29

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 29–30

- ^ Morgan 2006, p. 38

- ^ Morgan 2006, p. 42

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 39–41

- ^ Morgan 2006, p. 21

- ^ Morgan 2006, p. 43

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 44–45

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 46–47

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 42, 51

- ^ Morgan 2006, pp. 35–36

- ^ Morgan 2006, p. 36

- ^ Tacitus, Publius (2009). The Histories. Penguin Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-14-194248-3.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Otho. 7.

Bibliography

[edit]Ancient sources

[edit]- Plutarch, Life of Galba.

- Plutarch, Life of Otho.

- Suetonius, Life of Galba.

- Suetonius, Life of Otho.

- Suetonius, Life of Vitellius.

- Suetonius, Life of Vespasian.

Modern sources

[edit]- Wiedemann, T. E. J. (2010). "From Nero to Vespasian". In K. Bowman, Alan; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew (eds.). The Augustan Empire, 43 BC–AD 69. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26430-3.

- Connal, Robert (2012). "Rational Mutiny in the Year of the Four Emperors". Arctos: Acta Philologica Fennica. 46 (1): 33–52. ISSN 0570-734X.

- Flaig, Egon (2019). Den Kaiser herausfordern: die Usurpation im Römischen Reich. Campus Historische Studien (2. ed.). Frankfurt: Campus-Verl. pp. 356–416. ISBN 978-3-593-50952-5.

- Morgan, Gwyn (2006). 69 A.D: the year of four emperors. Oxford: Oxford University press. ISBN 978-0-19-512468-2.

- Murison, Charles L. (1993). Galba, Otho and Vitellius: careers and controversies. Spudasmata. Hildesheim: Olms. ISBN 978-3-487-09756-5.

- Nicolas, Etienne Paul (1979). De Neron à Vespasien: études et perspectives historiques suivies de l'analyse, du catalogue, et de la reproduction des monnaies "oppositionnelles" connues des années 67 à 70. T. 2. Ort nicht ermittelbar: Verlag nicht ermittelbar. ISBN 978-2-251-32831-7.

- Talbert, R.J.A. (1977). Badian, Ernst (ed.). "Some Causes of Disorder in A.D. 68-69". American Journal of Ancient History. 2 (1). Gorgias Press: 69–85. doi:10.31826/9781463237196-008. ISBN 978-1-4632-3719-6. ISSN 0362-8914.

- Martin, Peter-Hugo (1974). Die anonymen Münzen des Jahres 68 nach Christus (in German). Mainz: P. von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-0267-8.

- Wellesley, Kenneth; Levick, Barbara (2000). The Year of the four emperors. Roman imperial biographies (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23620-1.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch