Zoila Ugarte de Landívar

Zoila Ugarte de Landívar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | El Guabo, Ecuador |

| Died | Quito |

| Pen name | Zarelia |

| Language | Spanish |

| Signature | |

Zoila Ugarte de Landívar, also known by her pseudonym Zarelia, (June 27, 1864 – November 16, 1969) was an Ecuadorian writer, journalist, librarian, suffragist, and feminist.[1][2][3] She was the first female journalist in Ecuador.[4] Together with Hipatia Cárdenas de Bustamante, she was a key defender of women's suffrage in Ecuador.[5][6][7]

As an early figure in the realm of female Ecuadorian journalists, her career began in the late 1880s.[8][4] She began to use the journalistic pseudonym Zarella in the weekly publication Tesoro del Hogar.[8] She also became the first female director and editor of the political newspaper La Prensa in 1911.[9]

Early life

[edit]Ugarte was born in 1864 in El Guabo, Ecuador, to Juan de Dios Ugarte Benavides and Juana Seas Pérez. She was the fifth of 11 siblings.[3]

After the death of her parents, she moved to Guayaquil, where she became a supporter of the liberal cause and began working as a journalist in the late 1880s. She began to use the pseudonym Zarelia in the weekly Tesoro del Hogar, founded by Lastenia Larriva de Llona, which was published between 1887 and 1893.

Career

[edit]During Ugarte's early years contributing poems and short prose pieces to Tesoro del Hogar, she befriended various figures in Guayaquil's intellectual movement, such as Dolores Sucre and Numa Pompilio.[3]

La Mujer

[edit]Between 1895 and 1912 there was a boom of feminist writing in Ecuador, and Zoila Ugarte was one of the major figures of that movement. In 1905 she founded La Mujer, the country's first women's magazine. The magazine, which cost 40 cents at the time, contained articles about women's rights and their political, social, and workplace accomplishments. It also published stories, essays, and feminist articles written by women.[10]

The first editions of the magazine included contributions from such intellectuals of the period as Mercedes González de Moscoso, Ana María Albornoz, and Lastenia Larriva de Llona. Some of the authors contributed to the first issue anonymously, but beginning with the second issue the magazine's leaders pushed for them to write under their real names, with the goal of promoting writing by women in public spaces. In the first issue of La Mujer, Ugarte wrote:

"Ignorance is not a guarantee of bliss, no matter what they say—we will never be convinced that an educated woman is incapable of domestic virtues; it seems impossible to us that she who is able to comprehend that which is abstract cannot serve any such role, which does not require talent but only a little will. We women, like men, possess a conscious soul, a thinking mind, more or less brilliant."[11]

In the second edition of the magazine, Ugarte wrote a historical essay about the Battle of Pichincha. The issue also included poems and stories, as well as an article titled "La broma" ("The Joke") as a response to the negative comments made in response to the publication of La Mujer.

The magazine was shut down on various occasions because of its progressive messages and writing in favor of social and political rights for women.[10]

National Library

[edit]From 1911 until 1920, Ugarte worked as the director of the National Library of Ecuador in Quito. Much of her literary and historical work was published in the bulletin of this institution, known as El Boletín, which she founded in 1918. She also carried out a restructuring of library's administrative policies.

During this period, Ugarte oversaw the collection of documents pertaining to the Battle of Huachi, the colonization of Zamora, and the Universidad Santo Tomás de Aquino, now known as the Central University of Ecuador. She also worked to preserve and catalogue documents from the Quito archives and historic documents from the Real Audiencia of Quito, the early Ecuadorian republic, and various presidential correspondences.[7][10]

Sculpture

[edit]Ugarte complemented her passion for literature with another artistic endeavor: sculpture. In 1906, she enrolled in the Quito school of fine arts, which was founded during the presidency of Eloy Alfaro. There, she studied drawing, sculpture, lithography, and art history. Her work was reviewed in the Quito magazines Espejo and Revista de Bellas Artes, the latter of which she also contributed to, writing articles on aesthetics and art. In 1910 she held an exhibition of her work.[3]

Teaching

[edit]Ugarte taught at various schools in Quito including the Liceo Fernández Madrid girls' school and the Manuela Cañizares school.[3]

Activism

[edit]Liberalism

[edit]In the magazines La Mujer, La Prensa, and El Girto del Pueblo, Ugarte expressed her inclination toward liberalism and her criticism of social and political problems of the day.

On May 3, 1910, she published in the Quito newspaper La Patria an open letter directed to Ana Paredes de Alfaro, the wife of then-President Eloy Alfaro, in which she suggested Ana inform her husband that it would be prudent for him to leave power in order to prevent a lamentable situation for the Ecuadorian people.

In 1912 she continued publishing articles in favor of liberalism in the newspapers La Prensa and La Patria.[3]

Feminism

[edit]Ugarte was one of the earliest figures in Ecuador's liberal feminist movement in the early 20th century, as well as the growing workers' movement and broader class struggle. She was designated as an honorary member of the newspaper El Tipógrafo in 1905, and she wrote for the magazines El hogar cristiano, la Ondina del Guayas, and Alas, all of which formed part of the booming women's intellectual movement of the era. She founded the Anti-Clerical Feminist Center[12] and fought for that movement alongside fellow feminists such as Hipatia Cárdenas de Bustamante, Mercedes Gonzáles de Moscoso, and Delia Ibarra.

She not only fought for women's right to education, equality, and economic emancipation, but also for their right to vote and hold political office.

In 1922, Ugarte founded the Light of Pichincha Feminist Society (Sociedad Feminista Luz del Pichincha) alongside María Angélica Idrobo; she also served as the president of the organization. Through this organization, she created a primary school and a night school for women, both of which were free to attend. She also visited various women's prisons, whose conditions she decried in her publications.

In 1930, she invited feminists from the Spanish activist Belén de Sárraga's workshop to come speak at the Instituto Nacional Mejía in Quito. They subsequently traveled to various cities across the country, promoting women's rights. Ugarte then invited Belén de Sárraga herself to give a conference on feminism at the Guayas Workers' Confederation.

Ugarte represented Ecuador at the international feminist organization of the Committee of the Americas and at the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in the 1940s.[3]

Personal life

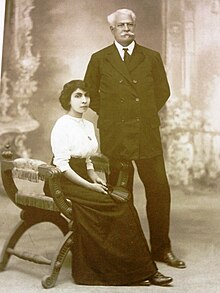

[edit]In 1893, she married the colonel Julio Landívar,[5][10] with whom she had her only son, Jorge Landívar Ugarte. He would later become a journalist and forerunner of the old Ecuadorian Socialist Party.[13]

Final years and recognition

[edit]During the final years of her life, Ugarte participated in various Quito cultural institutions, including serving as president of the city's Press Circle. She continued publishing articles in the newspaper El Universo and worked for both El Telégrafo and Espejo.[10] After the death of her son Jorge Landívar in 1962, she moved into a nursing home in Quito.[3]

She died in Quito on November 16, 1969, at nearly 105 years old.[5]

Ugarte received a medal of honor from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1937. Her journalistic work was also honored by the Zoila Ugarte Committee, overseen by the journalist Tulio Henriquez Cestaris in Guayaquil, which compiled an autograph album full of words of appreciation and recognition from her intellectual contemporaries. She was also honored by the Press Circle in 1966.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Staff Wilson, Mariblanca. (2005). Mujeres que dejaron huellas (1. ed.). Panamá, República de Panamá: [Universal Books]. ISBN 9962-02-721-7. OCLC 79434643.

- ^ Goetschel, Ana María. (2006). Orígenes del feminismo en el Ecuador. Quito: FLACSO. ISBN 978-9978-67-115-3. OCLC 1007058378.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rodas Morales, Raquel (January 2011). Zoila Ugarte de Landívar. Patriota y Republicana "Heroína ejemplar del feminismo". Quito, Ecuador. ISBN 978-9978-92-961-2.

- ^ a b Śniadecka-Kotarska, Magdalena. (2006). Ser mujer en Ecuador. Univ. de Varsovia, Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos. ISBN 83-89251-24-8. OCLC 255218717.

- ^ a b c Diccionario Biográfico Ecuador

- ^ Rodas, Raquel. (2009). Historia del voto femenino en el Ecuador. ISBN 978-9942-02-407-7. OCLC 608376107.

- ^ a b La Orense Zoila Ugarte y su faceta de primera periodista feminista del Ecuador

- ^ a b Guerra Cáceres, Alejandro (1990). Zoila Ugarte de Landívar : pionera del periodismo femenino del Ecuador. Vicerectorado Acad. OCLC 256799961.

- ^ La otra, Números. Editorial Uminasa del Ecuador. 1997.

- ^ a b c d e "Zoila Ugarte: Pionera del feminismo ecuatoriano". El Telegrafo. 2013-11-13.

- ^ Ugarte, Zoila (1905-04-15). "Editorial Revista". La Mujer.

- ^ La Orense Zoila Ugarte y su faceta de primera periodista feminista del Ecuador

- ^ "Family tree of Jorge Landivar". Geneanet. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch