Ulysses S. Grant - Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ulysses S. Grant | |

|---|---|

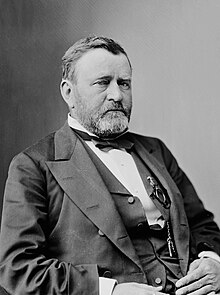

Portrait by Mathew Brady, c. 1870–1880 | |

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Mount McGregor, New York |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Dent Grant |

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was an American general who helped the Union Army of the United States win the American Civil War.[1] He was later the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877.[1]

Early life

[change | change source]Hiram Ulysses Grant was born on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio.[2] He was the oldest of six children born to Jesse and Hannah Grant.[2] Jesse Grant was a tanner. It was hard work, but he made a good living off of it.[2] Young Grant worked for his father in the tannery but hated the work.[2] He went to local schools. In 1838 he attended the Presbyterian Academy in Ripley, Ohio.[3] In 1839 he was appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point.[3] He was not the best student though he was good at math. When he graduated, he was placed in the infantry.[4]

When Grant arrived at West Point and discovered that the academy had him registered under the wrong name as "Ulysses S. Grant". He was told that it didn't matter what he or his parents thought his name was, the official government application said his name was "Ulysses S." and that application could not be changed. If "Hiram Ulysses Grant" wanted to attend West Point, he would have to change his name.[5]

Pre-presidency

[change | change source]Before becoming the president, Grant was an officer in the Union Army (North). He fought in the Mexican War and became a general at the start of the American Civil War. He served as head of the Army of Tennessee and won victories at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. He became the top general in the Union Army from 1864 to 1865, and fought several battles against Robert E. Lee.

Since he was able to do well fighting in the American Civil War, he gained popularity which helped him to become the candidate for president of the Republican party. The Republicans were then the strongest party. Even though he was a respected general and supported civil rights for African Americans, historians criticize his presidency because he appointed his friends into high political positions and tolerated their corruption (even though Grant himself was innocent). Grant was the youngest president, only 46 years old, and the first to have both his parents attend his inauguration.[6] He was also the first elected because of African American voters, who could vote then, although there was a big fight about it, which ended with many Black voters losing the right to vote. In his election, he won about 500,000 votes from African Americans, while the majority of white voters supported the Democratic candidate, who was called Horatio Seymour. Grant supported the right of Black men to vote because of this, but also because he thought it was right.

Presidency

[change | change source]In 1872, Republican reformers split the party and nominated Horace Greeley to be president. The Democratic Party also nominated him.[7] Greeley wanted Civil Service reform and amnesty for all former Confederates. Grant won the election by a landslide.[7]

Very soon into Grant's second term the Panic of 1873 started a depression in the United States that spread to Europe.[7] In 1873, Republicans in Congress were caught in a bribery scandal by newspapers. They had collected large bribes to give large federal grants to the railroads. The bribes had taken place before Grant was president, but the news came out during his presidency making it seem even more corrupt.[8] Also in 1873, Grant signed a bill that gave himself and congressmen a pay raise. The press attacked him for it calling it a money grab. Republicans were getting a bad reputation in the press. Mid-term, the Democrats won a majority of votes in the House. They started a number of congregational investigations. Grant's Secretary of the Treasury had to resign after being caught in a fraud scheme involving taxpayer kickbacks.

The Whiskey Ring was the largest scandal and involved widespread fraud.[8] Grant had appointed an army friend John MacDonald as an Internal Revenue Service supervisor for the St. Louis area. In return for bribes, whisky distillers paid taxes only on a small portion of the whiskey they produced.[8] They were cheating the U.S. government out of millions of dollars a year.[8] MacDonald kept some of the money while some of it went to the Republican Party.[8] The Whiskey Ring was paying some officials a regular salary to keep them from talking.[8] Benjamin Bristow, the Secretary of the Treasury at the time, had no idea this was going on.[8] Each time he sent inspectors on a raid to check out suspected cheaters, their records were always in good order.[8] Bristow had no idea someone in his office was telling them in advance who was to be inspected. Meanwhile, Grant accepted expensive gifts from MacDonald not suspecting he was running a fraud scheme.[8] MacDonald even told his friends in St. Louis that Grant was in on the scheme.[8] In 1875, MacDonald and more than 350 distillers and government officials were indicted.[8] This included Grant's personal secretary Orville Babcock. He was the one keeping ring members informed of any inspections.[8] At his trial, witnesses lied and even President Grant wrote a letter stating Babcock was of good character. As a result, Babcock was exonerated of the charges, but the scandal prevented him from going back to his job in Washington.[8] Of those accused, 60 paid fines while MacDonald and two others went to prison.[8] The Whiskey Ring proved to most Americans that Grant's administration was filled with corruption.[8]

Post-presidency

[change | change source]This section does not have any sources. (December 2020) |

After his presidency, Grant was suffering from throat cancer. He made a long trip to Europe and tried to become president again in 1880. Nobody had been elected three times before and it was seen as wrong by many because George Washington had refused to. In the end, the Republican party agreed to nominate (propose) congressman James Garfield instead. But Grant kept many supporters in the party. One of them shot Garfield the same year, and killed him. Grant never became president again, however, and only one man has been elected three or more times, Franklin Roosevelt. Grant was the first one to try, however.

Despite the problems during his second term, Grant was immensely popular, much like a modern-day movie star, and wrote a book about his life that sold millions of copies. He died three days after he finished writing it. He is buried with his wife Julia in Grant's Tomb, New York City, New York.

Historians once gave Grant a bad ranking due to cabinet members being corrupt. However, starting in 2000, scholars gave him a more favorable ranking because of better civil rights, the fact that Grant was not corrupt himself, and that he worked on parts of Lincoln's reconstruction.

References

[change | change source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Ulysses S. Grant Biography". Bio. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Ulysses S. Grant: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Timeline: Ulysses S. Grant". American Experience. PBS/WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ Martin Kelly. "Ulysses Grant - Eighteenth President of the United States". About Education. About.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ "Ulysses S. Grant" biography at Americancivilwar.com

- ↑ Presidential Parents and the Inauguration Archived 2013-06-02 at the Wayback Machine at Presidents Parents.com

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Ulysses S. Grant: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 "A Hero Betrayed: The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant". Constitutional Rights Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch