1824 United States presidential election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

261 members of the Electoral College 131 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 26.9%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

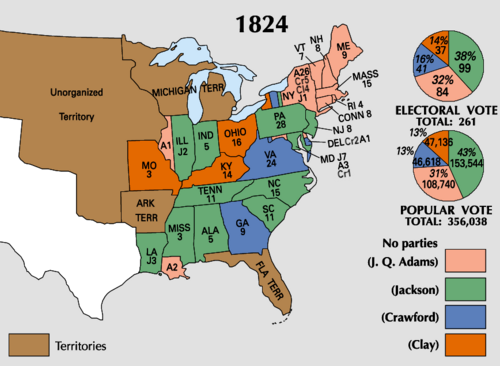

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Jackson, green denotes those won by Adams, orange denotes those won by Crawford, light yellow denotes those won by Clay. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1825 contingent U.S. presidential election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

24 state delegations of the House of Representatives 13 state votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

House of Representatives votes by state and district. States and districts in orange voted for Crawford, states and districts in green for Adams, and states and districts in blue for Jackson. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential elections were held in the United States from October 26 to December 2, 1824. Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford were the primary contenders for the presidency. The result of the election was inconclusive, as no candidate won a majority of the electoral vote. In the election for vice president, John C. Calhoun was elected with a comfortable majority of the vote. Because none of the candidates for president garnered an electoral vote majority, the U.S. House of Representatives, under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, held a contingent election. On February 9, 1825, the House voted (with each state delegation casting one vote) to elect John Quincy Adams as president, ultimately giving the election to him.[2][3]

The Democratic-Republican Party had won six consecutive presidential elections and by 1824 was the only national political party. However, as the election approached, the presence of multiple viable candidates resulted in there being multiple nominations by the contending factions, signaling the splintering of the party and an end to the Era of Good Feelings, as well as the First Party System.

Adams won New England, Jackson and Adams split the mid-Atlantic states, Jackson and Clay split the Western states, and Jackson and Crawford split the Southern states. Jackson finished with a plurality of the popular vote (there was no popular vote in six states including New York, the most populous state), and also of the electoral vote (due to the Three-fifths Compromise), while the other three candidates each finished with a significant share of the votes. Clay, who had finished fourth, was eliminated. Adams was the first son of a former president to become president.

This is one of two presidential elections (along with the 1800 election) that have been decided in the House. It is also one of five elections in which the winner did not achieve at least a plurality of the national popular vote and the only election in which the candidate who received the most electoral votes from the Electoral College did not win the election. It is also, to date, the election with the lowest popular vote percentage for an elected president (32.7%).

Background

[edit]The Era of Good Feelings, associated with the administration of President James Monroe, was a time of reduced emphasis on political party identity.[4] With the Federalists discredited, Democratic-Republicans adopted some key Federalist economic programs and institutions.[5][6] The economic nationalism of the Era of Good Feelings that would authorize the Tariff of 1816 and incorporate the Second Bank of the United States portended abandonment of the Jeffersonian political formula for strict construction of the Constitution, limited central government, and primacy of Southern slaveholding interests.[7][8][9]

An unintended consequence of wide single-party identification was reduced party discipline. Rather than political harmony, factions arose within the party.[10] Monroe attempted to improve discipline by appointing leading statesmen to his Cabinet, including Secretary of State John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford of Georgia, and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee led high-profile military missions. Only House Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky held political power independent of Monroe. He refused to join the cabinet and remained critical of the administration.

Two key events, the Panic of 1819 and the Missouri crisis of 1820, influenced and reshaped politics.[11] The economic downturn broadly harmed workers, the sectional disputes over slavery expansion raised tensions, and both events plus other factors drove demand for increased democratic control.[12] Social disaffection would help motivate revival of rivalrous political parties in the near future, though these had not yet formed by the time of the 1824 election.[13]

Nominations

[edit]Candidates who withdrew before election

[edit]The previous competition between the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party collapsed after the War of 1812 due to the disintegration of the Federalists' popular appeal. President James Monroe of the Democratic-Republicans was able to run effectively unopposed in the 1820 election. Like previous presidents who had been elected to two terms, Monroe declined to seek re-nomination for a third term.[14][page needed] The presidential nomination was thus left wide open within the Democratic-Republican Party, the only remaining major national political entity.

During the first year of Monroe's second term, it was said that 17 names had been mentioned as possible candidates, although formal nominations did not occur until late December. Among these possible candidates, William H. Crawford was seen as the most formidable, with many observers anticipating that John Quincy Adams would be his primary rival, and Henry Clay regarded as a likely outside contender. Crawford, a native of the Georgia frontier, was physically imposing and a powerful political figure. He was the first president pro tem of the Senate to be elected continuingly and had nearly beaten Monroe for the party nomination in 1816. As Secretary of the Treasury, he had helped to reorganized the nation's finances after the War of 1812 and establish the Second Bank of the United States. As such, he came to be seen as the treasury candidate.[15]

Crawford cultivated a strong base of support for the nomination, especially among influential political figures who could manage the congressional caucus and had, in the words of William Lowndes, his own "Organized Party" (the Old Republicans). Opponents accused him of consolidating power through the Tenure of Office Act of 1820, which required financial officeholders to be reappointed every four years. In creating a web of support among self-interested agents, Crawford became a man suspected of deliberately contriving his own election, something feared by all others. Despite these accusations, his supporters believed that he was not the conniving, maneuvering self-seeker his rivals branded him to be. It is impossible to know for certain, however, as little of his personal correspondence survives.[16]

Calhoun and Lowndes

[edit]The first people to be publicly nominated as candidates were Calhoun and Lowndes. Calhoun had been clashing with Crawford since the spring of 1820, when the latter began a retrenchment campaign in response to the Panic of 1819. Calhoun and his partisans viewed the effort as designed to emasculate the Department of War and discredit its secretary, especially as Congress failed to pass similar proposed reductions in the civil list.[17][18]

Calhoun, up until this point a staunch nationalist, shared many policy positions with Adams. Though claiming to prefer Adams, he feared that Adams could not defeat Crawford in the Southern and Middle states. Therefore, it fell upon him to challenge the assumption that Crawford was the favorite of the Southeast, hopefully defeating Crawford and his radicals. Overestimating his popularity, Calhoun believed that he could build a solid core of support by appealing to the economic interests of the two most powerful states, New York and Pennsylvania, and by consolidating his home base in the Southeast. In particular, he focused on Pennsylvania, where he made relations with the Family Party—a group of young Republican politicians in Philadelphia, led by George M. Dallas and Samuel D. Ingham, who opposed the state's Republican leaders that favored Crawford. In December, he was apparently nominated by the faction, and later that month, a group of congressmen, mainly from Pennsylvania, called on him in Washington and formally invited him to become a candidate, which he accepted after "some hesitation."[19][18]

Before the nomination, he had informed Lowndes of his intention to run for president early in his stay at Calhoun's residence in Washington, which began in December 1821. Lowndes, while having spoken positively of the other men, assured Calhoun he preferred his election. However, during Lowndes' journey to Washington, and without his knowledge, lowcountry moderates in the South Carolina legislature made an unprecedented move by attempting to nominate Lowndes. This effort was led by James Hamilton Jr., the Charleston delegation, and others from the tidewater parishes and Middle District counties east of the Broad River. They called a caucus of the legislature, which met in the hall of representatives on December 18, with about 2/3 of both houses in attendance. Opposition to the motion consisted primarily of upcountry partisans of Calhoun who, caught off guard, argued for delay, declaring the proposal premature and condemning the very idea that a single small state should attempt to name a president for the whole nation. While recognizing Calhoun's credentials, Lowndes' supporters argued that he was a more nationally prominent figure who would be more acceptable to citizens across the country. The motion to recommend Lowndes for president narrowly passed, 58 to 54, embarrassing Calhoun's campaign.[20]

The two men agreed not to alter their plans. Calhoun would enter the race as planned, while Lowndes would neither decline the nomination nor encourage an active campaign on his behalf, but follow the course dictated by his health. As this would most likely result in a voyage abroad, effectively removing Lowndes from further consideration, the difficulty presented by his nomination would be resolved, and supporters could transfer their backing to Calhoun. Despite this, his supporters remained insistent on his candidacy and encouraged him to stay. Lowndes died on October 27, 1822, en route to a recuperative visit to England.[21] The next month the legislature transferred their nomination to Calhoun.[22] Later, in February 1824, Dallas gave his support to Jackson's presidential campaign, with Calhoun as his running mate.[23]

Clinton, King, Thompson, and Tompkins

[edit]While Republicans in Northern states wished to support a man of their own, many were reluctant to rally behind Adams. By early 1823, critics among his supporters complained that Adams was "too fastidious and reserved," failing to engage in the political collaboration expected of a leader. They argued that presidents were no longer chosen purely on merit but rather through the influence of politicians and newspapers. His perceived "indifference" simply served to "chill and depress the kind feeling and fair exertions of his friends."[24]

Rather than endure such a leader, many potential supporters began searching for an alternative Northern candidate, though this effort ultimately proved fruitless. Rufus King was too old and also unwilling. Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins had long-since been dismissed as a viable successor to Monroe due to a combination of health problems and a financial dispute with the federal government, and he formally ruled himself out of making a presidential run at the start of 1824.[25][24] Secretary of the navy Smith Thompson, believing his New York ties might make him a viable option, delayed accepting a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court for eight months before being persuaded that he stood no chance of the presidency. Clinton, while having been supported by a small minority for president in 1820, suffered from the memory of his past involvements with Federalists, and in 1822 had become too electorally weak to compete, let alone win New York presidentially against the state's political machine.[26]

State legislative nominations

[edit]The Niles' Weekly Register, reporting on Washington politics in its January 26, 1822, issue, reported the names of Calhoun, Thompson, Clinton, Lowndes, Tompkins, Adams, Clay, and Crawford as being put forth as candidates. The newspaper also reported that "one or two others are casually spoken of" but did not identify them.[27] Lowndes' nomination had sparked intense speculation in Washington during the first week of the new year, concerned with the ramifications of the way Lowndes had been nominated. In a letter to his wife, Lowndes stated, "The House is in terrible confusion. I thought when I came here that the question was in fact confined to two persons Mr Crawford and Mr Adams. Now we have all the Secretaries and at least two who are not secretaries named..."[28]

That year, Kentucky and Missouri legislature caucuses nominated Clay, and Tennessee nominated Jackson. In January 1823, a meeting of Ohio legislators approved resolutions naming Clay. In early 1823, the legislatures of Massachusetts and Maine stated a preference for Adams but did not make a formal nomination, as they wished to ensure party unity nationwide. In January 1824, a caucus in the Mississippi legislature divided evenly between supporting Adams and Jackson. In Rhode Island, the "State Junta" initially committed itself in early 1824 to supporting the caucus candidate but soon realized they could not sway public opinion against Adams. Consequently, they refrained from pressing for Crawford out of fear of jeopardizing their state ticket. In early 1824, the Connecticut legislature nominated Adams. In March 1824, a state party convention at Harrisburg nominated Jackson. In June 1824, the New Hampshire legislature nominated Adams.[29]

The legislatures of Maine, New York, Virginia, and Georgia were in favor of the Congressional nominating caucus.[30]

Congressional nominating caucus

[edit]While not always popular, in past elections the party had relied on a congressional caucus, sometimes referred to as the "King Caucus," to nominate their presidential candidates, a process that had consistently succeeded in identifying the party favorite. Now, however, there was no certainty that the caucus would work again. Proponents, many of whom supported William H. Crawford, argued that it was essential for maintaining the stability of the republic and ensuring party unity on the presidential question. Opponents, including some of Crawford's own supporters, criticized the process as limiting the people's choice and effectively predetermining the outcome of the popular election.[31]

The strongest opposition came from Jacksonians. They viewed it as emblematic of the insider manipulation they sought to dismantle. On the other hand, New England Republicans, drawn to traditional party practices, had no such objection, and about 20 were believed to be willing to support Crawford if they could not have Adams, until Adams declared he would not accept a nomination for any office from a congressional caucus. In most delegations there were one or two representatives who, if left to themselves, were willing to attend the caucus. Crawford hoped to secure more than the 65 ballots that Monroe had obtained in 1816.[32]

In early February 1824, a majority of congressmen signed a public statement that they would not attend a nominating caucus. They believed that by refusing to attend instead of killing it, the caucus system would collapse on its own. On February 14, the caucus nominated Crawford for president and Albert Gallatin for vice president, but only 66 of the 240 Democratic-Republican members of Congress attended the caucus, which was viewed as a meeting of a special interest that wanted to pass itself off as representative of the whole Democratic-Republican Party. Gallatin had not sought the vice presidential nomination and soon withdrew at Crawford's request. Gallatin was also dissatisfied with repeated attacks on his credibility made by the other candidates. He was replaced by North Carolina senator Nathaniel Macon.[33][34][35]

| Presidential candidate | Ballot | Vice presidential candidate | Ballot |

|---|---|---|---|

| William H. Crawford | 62 | Albert Gallatin | 57 |

| John Quincy Adams | 2 | Erastus Root | 2 |

| Nathaniel Macon | 1 | John Quincy Adams | 2 |

| Andrew Jackson | 1 | Richard Rush | 1 |

| Walter Lowrie | 1 |

Adams sought to have Jackson be his vice-presidential running mate and Louisa Adams hosted a ball in honor of the Battle of New Orleans' ninth anniversary. He had supported Jackson during his invasion of Florida while Clay and Crawford opposed him, causing Jackson to oppose them. Clay supporters in the Tennessee legislature nominated Jackson for president in 1822, as an attempt to weaken Crawford in the state.[37]

Martin Van Buren and his political machine supported Crawford in New York.[38] During the selection of New York's electors Van Buren was able to deny Clay enough support to prevent him from being eligible for the contingent election.[39]

General election

[edit]Candidates

[edit]- Senator Andrew Jackson from Tennessee

All four candidates were nominated by at least one state legislature.[40] Andrew Jackson was recruited to run for the office of the president by the state legislature of Tennessee. Jackson did not seek the task of running for president. Instead, he wished to retire to his estate on the outskirts of Nashville, called the Hermitage.[41][better source needed]

Campaign

[edit]Candidates drew voter support by different states and sections. Adams dominated the popular vote in New England and won some support elsewhere, Clay dominated his home state of Kentucky and won pluralities in two neighboring states, and Crawford won the Virginia vote overwhelmingly and polled well in North Carolina. Jackson had geographically the broadest support, though there were heavy vote concentrations in his home state of Tennessee and in Pennsylvania and populous areas where even he ran poorly.

Policy played a reduced role in the election, though positions on tariffs and internal improvements did create significant disagreements. Both Adams and Jackson supporters backed Secretary of War John C. Calhoun of South Carolina for vice president. He easily secured the majority of electoral votes for that office. In reality, Calhoun was vehemently opposed to nearly all of Adams's policies, but he did nothing to dissuade Adams supporters from voting for him for vice president, partly because he was even more vehemently opposed to the prospect of a Clay presidency, and partly because he had a long-standing personal enmity with Crawford.

The campaigning for presidential election of 1824 took many forms. Contrafacta, or well known songs and tunes whose lyrics have been altered, were used to promote political agendas and presidential candidates. Below can be found a sound clip featuring "Hunters of Kentucky", a tune written by Samuel Woodsworth in 1815 under the title "The Unfortunate Miss Bailey". Contrafacta such as this one, which promoted Andrew Jackson as a national hero, have been a long-standing tradition in presidential elections. Another form of campaigning during this election was through newsprint. Political cartoons and partisan writings were best circulated among the voting public through newspapers. Presidential candidate John C. Calhoun was one of the candidates most directly involved through his participation in the publishing of the newspaper The Patriot as a member of the editorial staff. This was a sure way to promote his own political agendas and campaign. In contrast, most candidates involved in early 19th century elections did not run their own political campaigns. Instead it was left to volunteer citizens and partisans to speak on their behalf.[42][43][44][45]

Results

[edit]The 1824 presidential election marked the final collapse of the Republican-Federalist political framework. The electoral map confirmed the candidates' sectional support, with Adams winning in New England, Jackson having wide voter appeal, Clay attracting votes from the West, and Crawford attracting votes from the eastern South. Jackson earned only a plurality of electoral votes. Thus, the presidential election was decided by the House of Representatives, which elected John Quincy Adams on the first ballot. John C. Calhoun, supported by Adams and Jackson, easily won the vice presidency, not requiring a contingent election in the Senate.

Jackson's electoral college plurality was the result of the Three-fifths Compromise. The electoral college results would have been 83 for Adams and 77 for Jackson without the inflated electoral count of slaveholding states. Crawford likewise benefited in this regard, as all but eight of his electoral votes were from slave states, while Clay's electoral votes were split relatively evenly (20 from the free states of New York and Ohio, 17 from the slave states of Kentucky and Missouri); without the Three-fifths Compromise, Crawford would have finished last in the electoral college, and Clay would have entered the contingent election at his expense.[46]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote[a] | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| Andrew Jackson[c] | Democratic-Republican | Tennessee | 151,309 | 40.45% | 99 |

| John Quincy Adams[d] | Democratic-Republican | Massachusetts | 122,440 | 32.74% | 84 |

| William H. Crawford[e] | Democratic-Republican | Georgia | 41,222 | 11.02% | 41 |

| Henry Clay[f] | Democratic-Republican | Kentucky | 48,606 | 13.00% | 37 |

| Unpledged electors | None | NA | 10,449 | 2.79% | 0 |

| Total | 374,026 | 100.0% | 261 | ||

| Needed to win | 131 | ||||

| Vice presidential candidate | Party | State | Electoral vote[48] |

|---|---|---|---|

| John C. Calhoun | Democratic-Republican | South Carolina | 182 |

| Nathan Sanford | Democratic-Republican | New York | 30 |

| Nathaniel Macon | Democratic-Republican | North Carolina | 24 |

| Andrew Jackson | Democratic-Republican | Tennessee | 13 |

| Martin Van Buren | Democratic-Republican | New York | 9 |

| Henry Clay | Democratic-Republican | Kentucky | 2 |

| Total | 260 | ||

| Needed to win | 131 | ||

Maps

[edit]- Electoral College vote

- Map of presidential election results by county, shaded according to the vote share of the highest result for an elector of any given candidate

- Map of presidential election results by electoral district, shaded according to the vote share of the highest result for an elector of any given candidate. Electoral boundaries for Maryland could not be found

- Map of presidential election Results by county, shaded according to the vote share of the highest result for an elector candidate pledged to Jackson

- Map of presidential election Results by county, shaded according to the vote share of the highest result for an elector candidate pledged to Adams

- Map of presidential election Results by county, shaded according to the vote share of the highest result for an elector candidate pledged to Clay

- Map of presidential election Results by county, shaded according to the vote share of the highest result for an elector candidate pledged to Crawford

- Map of presidential election results by county, shaded according to the vote share of the highest result for an elector candidate not pledged to support any particular presidential or vice presidential candidate

Results by state

[edit]Elections in this period were vastly different from modern-day presidential elections. The actual presidential candidates were rarely mentioned on tickets and voters were voting for particular electors who were pledged to a particular candidate. There was sometimes confusion as to who a particular elector was actually pledged to. Results are reported as the highest result for an elector for any given candidate. For example, if three Jackson electors received 100, 50, and 25 votes, Jackson would be recorded as having 100 votes. Confusion surrounding the way results are reported may lead to discrepancies between the sum of all state results and national results.

| States/districts won by Jackson/Calhoun |

| States/districts won by Adams/Calhoun |

| States/districts won by Crawford/Macon |

| States/districts won by Clay/Sanford |

| Andrew Jackson Democratic-Republican | John Quincy Adams Democratic-Republican | Henry Clay Democratic-Republican | William Crawford Democratic-Republican | Other | State total | Citation | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes | # | % | electoral votes | # | % | electoral votes | # | % | electoral votes | # | % | electoral votes | # | % | # | ||

| Alabama | 5 | 9,461 | 69.35 | 5 | 2,422 | 17.75 | 0 | 96 | 0.70 | 0 | 1,663 | 12.19 | 0 | no ballots | 13,642 | AL | [49] | |

| Connecticut | 8 | no ballots | 0 | 9,261 | 82.20 | 8 | no ballots | 0 | 1,978 | 17.56 | 0 | 27+ | 0.24 | 11,266 | CT | [50] | ||

| Delaware | 3 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 1 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 2 | no popular vote | – | DE | ||||||

| Georgia | 9 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 9 | no popular vote | – | GA | ||||||

| Illinois | 3 | 1,272 | 27.02 | 2 | 1,541 | 32.74 | 1 | 1,047 | 22.24 | 0 | 847 | 17.99 | 0 | no ballots | 4,707 | IL | [51] | |

| Indiana | 5 | 7,444 | 46.94 | 5 | 3,093 | 19.50 | 0 | 5,321 | 33.55 | 0 | no ballots | 0 | 1 | 0.01 | 15,859 | IN | [52] | |

| Kentucky | 14 | 6,658 | 27.76% | 0 | 120 | 0.50% | 0 | 17,207 | 71.73% | 14 | 3 | 0.01% | 0 | no ballots | 23,988 | KY | [53] | |

| Louisiana | 5 | no popular vote | 3 | no popular vote | 2 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | – | LA | ||||||

| Maine | 9 | no ballots | 0 | 9,412 | 75.33 | 9 | no ballots | 0 | 3,081 | 24.66 | 0 | 1+ | 0.01 | 12,494 | ME | [54] | ||

| Maryland | 11 | 14,473 | 44.22 | 7 | 14,191 | 43.36 | 3 | 695 | 2.12 | 0 | 3,371 | 10.30 | 1 | no ballots | 32,730 | MD | [55] | |

| Massachusetts | 15 | no ballots | 0 | 37,891 | 84.53 | 15 | no ballots | 0 | no ballots | 0 | 6,933 | 15.47 | 44,824 | MA | [56] | |||

| Mississippi | 3 | 3,313 | 64.04 | 3 | 1,718 | 33.21 | 0 | 21 | 0.41 | 0 | 121 | 2.34 | 0 | no ballots | 5,173 | MS | [57] | |

| Missouri | 3 | 1,166 | 33.96 | 0 | 191 | 5.56 | 0 | 2,042 | 59.48 | 3 | 34 | 0.99 | 0 | no ballots | 3,433 | MO | [58] | |

| New Hampshire | 8 | no ballots | 0 | 10,203 | 75.70 | 8 | no ballots | 0 | no ballots | 0 | 3,275 | 24.30 | 13,478 | NH | [59] | |||

| New Jersey | 8 | 10,342 | 51.22 | 8 | 8,405 | 41.63 | 0 | no ballots | 0 | 1,232 | 6.10 | 0 | 211 | 1.05 | 20,190 | NJ | [60] | |

| New York | 36 | no popular vote | 1 | no popular vote | 26 | no popular vote | 4 | no popular vote | 5 | no popular vote | – | NY | ||||||

| North Carolina | 15 | 20,418 | 56.64 | 15 | no ballots | 0 | no ballots | 0 | 15,629 | 43.36 | 0 | 1 | 0.003 | 36,048 | NC | [61] | ||

| Ohio | 16 | 18,411 | 36.63 | 0 | 12,686 | 25.24 | 0 | 19,165 | 38.13 | 16 | no ballots | 0 | no ballots | 50,262 | OH | [62] | ||

| Pennsylvania | 28 | 36,091 | 76.13 | 28 | 5,424 | 11.44 | 0 | 1,703 | 3.59 | 0 | 4,189 | 8.84 | 0 | no ballots | 47,407 | PA | [63] | |

| Rhode Island | 4 | no ballots | 0 | 2,144 | 91.47 | 4 | no ballots | 0 | 200 | 8.53 | 0 | no ballots | 2,344 | RI | [64] | |||

| South Carolina | 11 | no popular vote | 11 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | – | SC | ||||||

| Tennessee | 11 | 19,285 | 93.10 | 11 | 224 | 1.08 | 0 | 890 | 4.30 | 0 | 316 | 1.53 | 0 | no ballots | 20,715 | TN | [65] | |

| Vermont | 7 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 7 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | 0 | no popular vote | – | VT | ||||||

| Virginia | 24 | 2,975 | 19.35 | 0 | 3,514 | 22.24 | 0 | 419 | 2.73 | 0 | 8,558 | 55.68 | 24 | no ballots | 15,371 | VA | [66] | |

| TOTALS: | 261 | 151,309 | 40.45 | 99 | 122,440 | 32.74 | 84 | 48,606 | 13.00 | 37 | 41,222 | 11.02 | 41 | 10,449 | 2.79 | 374,026 | US | |

| TO WIN: | 131 | |||||||||||||||||

Vice presidential electoral vote breakdown by ticket

[edit]| Electoral votes for President | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Andrew Jackson | John Q. Adams | William H. Crawford | Henry Clay | |

| John C. Calhoun | 182 | 99 | 74 | 2 | 7 |

| Nathan Sanford | 30 | – | – | 3 | 27 |

| Nathaniel Macon | 24 | – | – | 24 | – |

| Andrew Jackson | 13 | – | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| Martin Van Buren | 9 | – | – | 9 | – |

| Henry Clay | 2 | – | – | 2 | – |

| (No vote for vice president) | 1 | – | 1 | – | – |

| Total | 261 | 99 | 84 | 41 | 37 |

Close states

[edit]States where the margin of victory was under 1%:

- Maryland 0.32% (109 votes)

States where the margin of victory was under 5%:

- Ohio 1.53% (766 votes)

States where the margin of victory was under 10%:

- Illinois 5.23% (244 votes)

1825 contingent election

[edit]As no presidential candidate had won an absolute electoral vote majority, the responsibility for electing a new president devolved upon the U.S. House of Representatives, which held a contingent election on February 9, 1825. As prescribed by the Twelfth Amendment, the House was limited to choosing from among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and William Crawford; Henry Clay, who had finished fourth, was eliminated.[67] Each state delegation, voting en bloc, had a single vote. There were 24 states at the time, thus an absolute majority of 13 votes was required for victory.

Clay detested Jackson and had said of him, "I cannot believe that killing 2,500 Englishmen at New Orleans qualifies for the various, difficult, and complicated duties of the Chief Magistracy."[68] Moreover, Clay's American System was closer to Adams's position on tariffs and internal improvements than Jackson's. Even if Clay had wished to align with Crawford over Jackson, which was highly unlikely in any event since Clay's policy differences with Crawford were even deeper, especially on matters of the tariff, Crawford had been in poor health, and no path to victory was evident.

Daniel Pope Cook, Illinois' sole representative, was anti-slavery and gave his support to Adams. James Buchanan attempted to make a compromise with Clay in which Jackson would make him Secretary of State in exchange for his support. Clay instead gave his support to Adams and was able to have the Kentucky, Missouri, and Ohio delegations support him. Illinois, Louisiana, and Maryland, which Jackson won during the election, had their delegations support Adams.[69]

Van Buren attempted to have New York's delegation be divided between Adams and Crawford in order to increase its power and make a deal with one of them. However, Stephen Van Rensselaer, a Federalist allied with Van Buren, voted for Adams. Van Buren stated that Van Rensselaer found a ballot for Adams on the floor while Van Rensselaer, in his letter to Governor DeWitt Clinton, stated that he voted for Adams as he was bound to win and that he wanted to shorten "the long agony". Van Buren supported Jackson during the 1828 election and aided in Calhoun's selection as vice president.[70]

Ignoring the nonbinding directive of the Kentucky legislature that its House delegation choose Jackson, the delegation voted 8–4 for Adams instead.[71] Thus, Adams was elected president on the first ballot,[72][73] with 13 states, followed by Jackson with seven, and Crawford with four.

Balloting in the contingent election

[edit]

| February 9, 1825 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | % | |||||||||||||||||

| John Quincy Adams | 13 | 54.17 | |||||||||||||||||

| Andrew Jackson | 7 | 29.17 | |||||||||||||||||

| William H. Crawford | 4 | 16.67 | |||||||||||||||||

| Total votes | 24 | 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| Votes necessary | 13 | 54.17 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Aftermath

[edit]Adams' victory shocked Jackson, who, as the winner of a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, expected the House to choose him. Not long before the contingent House election, an anonymous statement appeared in a Philadelphia paper, called the Columbian Observer. The statement, said to be from a member of Congress, essentially accused Clay of selling Adams his support for the office of Secretary of State. No formal investigation was conducted, so the matter was neither confirmed nor denied. When Clay was indeed offered the position after Adams was victorious, he opted to accept and continue to support the administration he voted for, knowing that declining the position would not have helped to dispel the rumors brought against him.[77] Jackson referred to Clay as the "Judas of the West".[78]

By appointing Clay his Secretary of State, President Adams essentially declared him heir to the presidency, as Adams and his three predecessors had all served as Secretary of State. Jackson and his followers accused Adams and Clay of striking a "corrupt bargain", and the Jacksonians would campaign on this claim for the next four years, ultimately helping Jackson defeat Adams in 1828. Ironically, Adams offered Jackson a position in his Cabinet as Secretary of War, which Jackson declined to accept.

Adams' supporters controlled the U.S. House of Representatives after the 1824–25 elections and obtained the speakership for John W. Taylor. Adams' relationship with Calhoun deteriorated, with Calhoun opposing Clay's appointment as Secretary of State due to his own presidential ambitions. In June 1826, Calhoun gave his support to Jackson for the 1828 election.[79]

Electoral College selection

[edit]

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| Each elector chosen by voters statewide | |

| Each elector appointed by state legislature | |

| State divided into electoral districts, with one elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | |

| Maine |

See also

[edit]- Contested elections in American history

- United States presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e The popular vote figures exclude Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, and Vermont. In all of these states, the Electors were chosen by the state legislatures rather than by popular vote.[47]

- ^ Albert Gallatin had originally been nominated to serve as Crawford's running mate; however, Gallatin withdrew the nomination and Macon was chosen instead.

- ^ Jackson was nominated by the Tennessee state legislature and by the Democratic Party of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Adams was nominated by the Massachusetts state legislature.

- ^ Crawford was nominated by a caucus of 66 congressmen that called itself the "Democratic members of Congress".

- ^ Clay was nominated by the Kentucky state legislature.

References

[edit]- ^ "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- ^ Robin Kolodny, "The Several Elections of 1824." Congress & the Presidency: A Journal of Capital Studies 23#2 (1996) online[dead link].

- ^ George Dangerfield, George. The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815-1828 (1965) pp 212–230.

- ^ Ammon, 1958, p. 4: "The phrase 'Era of Good Feelings", so inextricably associated with the administration of James Monroe ..."

- ^ Ammon, 1958, p. 5: "Most Republicans like former President [James] Madison readily acknowledged the shift that had taken place within the Republican party towards Federalist principles and viewed the process without qualms." And p. 4: "The Republicans had taken over (as they saw it) that which was of permanent value in the Federal program." And p. 10: "Federalists had vanished" from national politics.

- ^ Brown, 1966, p. 23: "a new theory of party amalgamation preached the doctrine that party division was bad and that a one-party system best served the national interest" and "After 1815, stirred by the nationalism of the post-war era, and with the Federalists in decline, the Republicans took up the Federalist positions on a number of the great public issues of the day, sweeping all before them as they did. The Federalists gave up the ghost."

- ^ Brown, 1966, p. 23: The amalgamated Republicans, "as a party of the whole nation ... ceased to be responsive to any particular elements in its constituency. It ceased to be responsive to the South." And "The insistence that slavery was uniquely a Southern concern, not to be touched by outsiders, had been from the outset a sine qua non for Southern participation in national politics. It underlay the Constitution and its creation of a government of limited powers ..."

- ^ Brown, 1966, p. 24: "Not only did the Missouri crisis make these matters clear [the need to revive strict constructionist principles and quiet anti-slavery agitation], but 'it gave marked impetus to a reaction against nationalism and amalgamation of postwar Republicanism'" and the rise of the Old Republicans.

- ^ Ammon, 1971 (James Monroe bio) p. 463: "The problems presented by the [consequences of promoting Federalist economic nationalism] gave an opportunity to the older, more conservative [Old] Republicans to reassert themselves by attributing the economic dislocation to a departure from the principles of the Jeffersonian era."

- ^ Parsons, 2009, p. 56: "Animosity between Federalists and Republicans had been replaced by animosity between Republicans themselves, often over the same issues that had once separated them from the Federalists."

- ^ Wilentz, 2008, p. 251–252: "The panic ... was pivotal ... the hard times of 1819 and early 1820s revive[d] ... fundamental questions about the nationalist economic policies of the new-style Republicans under Madison and Monroe, and focused inchoate popular resentments on the banks, especially the Second BUS." p. 252: "The Missouri controversy ... proved for more important than the [incidental] outbursts."

- ^ Wilentz, 2008, p. 252: "Both the panic and the Missouri debates underscored in different ways the overriding question of democracy as Americans perceived it. In economic matters, the questions arose primarily as a matter of privilege. Should unelected private interests, well connected to government, be permitted to control, to their own benefit, the economic destiny of the entire nation?"

- ^ Hofstadter, 1947, p. 51: The "general mass of the disaffection to the Government was not sufficiently concentrated to prevent re-election, unopposed, of President Monroe in 1820 in the absence of a national opposition party; but it soon transformed politics in many states. Debtors rushed into politics to defend themselves, and secured moratoriums and relief laws from the legislatures of several Western states ... A popular demand arose for laws to prevent imprisonment for debt, for a national bankruptcy law, and for a new tariff and public land policies. For the first time Americans thought of politics as having an intimate relation to their welfare."

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 25–27; 33.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 27.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 35.

- ^ a b Vipperman 1989, p. 253.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 35–36.

- ^ Vipperman 1989, p. 254–255.

- ^ Vipperman 1989, p. 255–264.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Hay 1935, p. 39.

- ^ a b Ratcliffe 2015, p. 62.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Daniel D. Tompkins, 6th Vice President (1817-1825)". www.senate.gov.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 49; 62; 79.

- ^ Niles' weekly register v.21 1821-1822. p. 352. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Vipperman 1989, p. 259.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 62–66; 102; 118–119.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 151.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 149–151.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 152–153.

- ^ Patrick, John J.; Pious, Richard M.; Ritchie, Donald A. (2001). The Oxford Guide to the United States Government. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-514273-0.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 206.

- ^ Ratcliffe 2015, p. 154.

- ^ Bonney, Catharina V. R. (1875). A Legacy of Historical Gleanings. J. Munsell. p. 410.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 205-206.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 203.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 240.

- ^ Presidential Elections, 1789-2008 County, State, and National Mapping of Election Data; Donald R. Deskins, Jr., Hanes Walton, Jr., and Sherman C. Puckett; University of Michigan Press, 2010; p. 80

- ^ Bradley, Harold. "Andrew Jackson". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Hansen, Liane (October 5, 2008). "Songs Along The Campaign Trail". Election 2008: On The Campaign Trail (Radio series episode). National Public Radio.

- ^ Hay, Thomas R. (October 1934). "John C. Calhoun and the Presidential Campaign of 1824, Some Unpublished Calhoun Letters". The American Historical Review. 40 (1): 82–96. doi:10.1086/ahr/40.1.82. JSTOR 1838676.

- ^ McNamara, R. (September 2007). "The Election of 1824 Was Decided in the House of Representatives". About.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ Schimler, Stuart (February 12, 2002). "Singing to the Oval Office: A Written History of the Political Campaign Song". President Elect Articles. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 208.

- ^ Leip, David. "1824 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 26, 2005.

- ^ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ McNamara, Robert (February 11, 2020). "The Election of 1824 Was Decided in the House of Representatives". thoughtco.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Henry Clay to Francis Preston Blair, January 29, 1825.[full citation needed]

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 209-210.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 240-241.

- ^ "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Henry Clay (1777–1852)". Office of the Historian.

- ^ Adams, John Quincy; Adams, Charles Francis (1874). Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848. J.B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 501–505. ISBN 978-0-8369-5021-2. Retrieved August 2, 2006 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ United States Congress (1825). House Journal. 18th Congress, 2nd Session, February 9. pp. 219–222. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- ^ "1 Cong. Deb. 527 (1825)". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ McMaster, J. B. (1900). History of the People of the United States... Vol. V. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 81. Reprinted in Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1965). John Quincy Adams and the Union. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 54.

- ^ "1824 US House Vote for President". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Schlesinger, Arthur Meier; Israel, Fred L. (1971). History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–1968, Volume I, 1789–1844. New York: Chelsea House. pp. 379–381. ISBN 978-0070797864. Retrieved November 19, 2008 – via Google Books.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 211.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 249-250.

- ^ Akin (1824). "Caucus curs in full yell, or a war whoop, to saddle on the people, a pappoose president / J[ames] Akin, Aquafortis". Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Ammons, Harry. 1959. "James Monroe and the Era of Good Feelings". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, LXVI, No. 4 (October 1958), pp. 387–398, in Essays on Jacksonian America, Ed. Frank Otto Gatell. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

- Brown, Richard H. 1966. "The Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism". South Atlantic Quarterly, pp. 55–72, in Essays on Jacksonian America, Ed. Frank Otto Gatell. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

- Dangerfield, George. 1965. The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815-1828. New York: Harper & Row. online

- Ratcliffe, Donald (2014). "Popular Preferences in the Presidential Election of 1824". Journal of the Early Republic. 34 (1): 45–77. doi:10.1353/jer.2014.0009. JSTOR 24486931. S2CID 155015965.

- Kolodny, Robin. "The Several Elections of 1824." Congress & the Presidency: A Journal of Capital Studies 23#2 (1996) online[dead link].

- Wilentz, Sean. 2008. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: Horton.

Works cited

[edit]- Hay, Thomas (1935). "John C. Calhoun and the Presidential Campaign of 1824 Some Unpublished Calhoun Letters". North Carolina Historical Review. 12 (1). North Carolina Office of Archives and History: 20–44. JSTOR 23515151.

- Howe, Daniel (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7.

- Ratcliffe, Donald (2015). The One-Party Presidential Contest: Adams, Jackson, and 1824's Five-Horse Race. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700621309.

- Vipperman, Carl J. (1989). William Lowndes and the transition of Southern politics, 1782-1822. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807818268.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Everett S. (1925). "The Presidential Election of 1824–1825". Political Science Quarterly. 40 (3): 384–403. doi:10.2307/2142211. JSTOR 2142211.

- Kolodny, Robin. "The Several Elections of 1824." Congress & the Presidency 23#2 (1996) online.

- Morgan, William G. "John Quincy Adams Versus Andrew Jackson: Their Biographers And The 'Corrupt Bargain' Charge." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 26#1 (1967), pp. 43–58. online

- Morgan, William G. "Henry Clay's Biographers and the 'Corrupt Bargain' Charge." Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 66#3 (1968), pp. 242–58. online

- Nagel, Paul C. (1960). "The Election of 1824: A Reconsideration Based on Newspaper Opinion". Journal of Southern History. 26 (3): 315–329. doi:10.2307/2204522. JSTOR 2204522.

- Ratcliffe, Donald J. The One-Party Presidential Contest: Adams, Jackson, and 1824's Five-Horse Race (University Press of Kansas, 2015) xiv, 354 pp.

- Murphy, Sharon Ann. "A Not-So-Corrupt Bargain". Review of The One-Party Presidential Contest: Adams, Jackson and 1824's Five-Horse Race by Donald Ratcliffe. Common-place, Vol. 16, No. 4.

External links

[edit]- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved March 20, 2005.

- Presidential Election of 1824: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Election of 1824 in Counting the Votes Archived November 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch