2024 United Kingdom general election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 650 seats in the House of Commons 326[n 1] seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 59.9% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

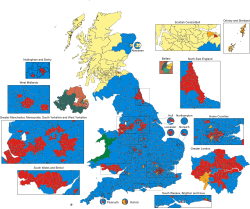

A map presenting the results of the election, by party of the MP elected from each constituency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Composition of the House of Commons after the election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 2024 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday, 4 July 2024 to elect 650 members of Parliament to the House of Commons, the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The opposition Labour Party, led by Keir Starmer, defeated the governing Conservative Party, led by Rishi Sunak, in a landslide.

The election was the first general election victory for the Labour Party since 2005, and ended the Conservative Party's fourteen-year tenure as the primary governing party. Labour achieved a 174-seat simple majority and a total of 411 seats,[a] the party's second-best result in terms of seat share following the 1997 general election. The party's vote share of 33.7 per cent was the smallest of any majority government in British history. Labour won 211 more seats than the previous general election in 2019, but received fewer total votes. The party became the largest in England for the first time since 2005, in Scotland for the first time since 2010, and retained its status as the largest party in Wales.[3] It lost seven seats: five to independent candidates, largely attributed to its stance on the Israel–Hamas war; one to the Green Party of England and Wales; and one to the Conservatives. The Conservative Party was reduced to 121 seats on a vote share of 23.7 per cent, the worst result in its history. It lost 251 seats in total, including those of twelve Cabinet ministers and that of the former prime minister Liz Truss.[4] It also lost all its seats in Wales.[5]

Smaller parties performed well in the election, in part due to anti-Conservative tactical voting, and the combined Labour and Conservative vote share of 57.4 per cent was the lowest since the 1918 general election. The Liberal Democrats, led by Ed Davey, made the most significant gains by winning a total of seventy-two seats. This was the party's best-ever result and made it the third-largest party in the Commons, a status it had previously held but lost at the 2015 general election.[6] Reform UK achieved the third-highest vote share and won five seats, and the Green Party of England and Wales won four seats; both parties achieved their best parliamentary results in history, winning more than one seat for the first time. In Wales, Plaid Cymru won four seats. In Scotland, the Scottish National Party was reduced from forty-eight seats to nine and lost its status as the third-largest party in the Commons.[7] In Northern Ireland, which has a distinct set of political parties,[8] Sinn Féin retained its seven seats and therefore became the largest party; this was the first election in which an Irish nationalist party won the most seats in Northern Ireland. The Democratic Unionist Party won five seats, a reduction from eight at the 2019 general election. The Social Democratic and Labour Party won two seats, and the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, the Ulster Unionist Party, Traditional Unionist Voice, and an independent candidate won one seat each.

Labour entered the election with a large lead over the Conservatives in opinion polls, and the potential scale of the party's victory was a topic of discussion during the campaign period.[9][10] The economy, healthcare, education, infrastructure development, immigration, housing and energy were also campaign topics. The election was the first fought using the new constituency boundaries implemented after the 2023 Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, the first general election in which photographic identification was required to vote in person in Great Britain,[e] and the first called under the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act 2022.[11]

Background[edit]

Political background of the Conservatives before the election[edit]

The Conservative Party under Boris Johnson won a large majority at the 2019 general election and the new government passed the Brexit withdrawal agreement.[12][13] The COVID-19 pandemic saw the government institute public health restrictions, including limitations on social interaction, that Johnson and some of his staff were later found to have broken. The resulting political scandal (Partygate), one of many in a string of controversies that characterised Johnson's premiership, damaged his personal reputation.[14][15] The situation escalated with the Chris Pincher scandal in July 2022, leading to Johnson's resignation.[16] He resigned as an MP the following year,[17] after an investigation unanimously found that he had lied to Parliament.[18]

Liz Truss won the resultant leadership election and succeeded Johnson in September.[19][20] Truss announced large-scale tax cuts and borrowing in a mini-budget on 23 September, which was widely criticised and – after it rapidly led to financial instability – largely reversed.[21] She resigned in October, making her the shortest-serving prime minister in British history.[22] Rishi Sunak won the resultant leadership election unopposed to succeed Truss in October.[23][24]

During his premiership, Sunak was credited with improving the economy and stabilising national politics following the premierships of his predecessors,[25] although many of his pledges and policy announcements ultimately went unfulfilled.[26][27] He did not avert further unpopularity for the Conservatives who, by the time of Sunak's election, had been in government for 12 years. Public opinion in favour of a change in government was reflected in the Conservatives' poor performance at the 2022, 2023 and 2024 UK local elections.[28]

Political background of other parties before the election[edit]

2024 United Kingdom general election (4 July) | |

|---|---|

| Parties | |

| Campaign | |

| Overview by country | |

| Outcome | |

| Related | |

| |

Keir Starmer won the Labour Party's 2020 leadership election, succeeding Jeremy Corbyn.[29] Under his leadership, Starmer repositioned the party away from the left and toward the political centre.[30][31] He emphasised the importance of eliminating antisemitism within the party, which had been a controversial issue during Corbyn's leadership. The political turmoil from the Conservative scandals and government crises led to Labour having a significant lead in polling over the Conservatives, often by very wide margins, since late 2021, coinciding with the start of the Partygate scandal.[14][15] During the 2023 local elections, Labour gained more than 500 councillors and 22 councils, becoming the largest party in local government for the first time since 2002.[32] Labour made further gains in the 2024 local elections, including winning the West Midlands mayoral election.[33]

Ed Davey, who previously served in the Cameron–Clegg coalition government, won the Liberal Democrat's 2020 leadership election, succeeding Jo Swinson, who lost her seat in the previous general election.[34] Davey prioritised defeating the Conservatives and ruled out working with them following the election.[35] The Liberal Democrats made gains in local elections: in the 2024 local elections, the Liberal Democrats finished second for the first time in a local election cycle since 2009.[36]

Like the Conservatives, the Scottish National Party (SNP) suffered political turmoil and saw a decrease in their popularity in opinion polling, with multiple party leaders and First Ministers (Nicola Sturgeon, Humza Yousaf and John Swinney) and the Operation Branchform police investigation. Sturgeon claimed occupational burnout was the reason for her resignation,[37] while Yousaf resigned amid a government crisis following his termination of a power-sharing agreement with the Scottish Greens.[38] When Swinney assumed the leadership after being elected unopposed to succeed Yousaf, the SNP had been in government for 17 years.[39]

Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay took over leadership of the Green Party of England and Wales from Caroline Lucas. Rhun ap Iorwerth took over leadership of Plaid Cymru. Mary Lou McDonald took over leadership of Sinn Féin. The Brexit Party rebranded as Reform UK, and was initially led by Richard Tice in the years preceding the election before Nigel Farage resumed leadership during the election campaign.[40]

Edwin Poots took over as the Democratic Unionist Party leader in May 2021 but lasted only 20 days. He was replaced by Jeffrey Donaldson, who resigned in March 2024 after being arrested on charges relating to historical sex offences. He appeared in court on 3 July, the day before polling day, to face additional sex offence charges.[41][42] Gavin Robinson initially took over as interim leader,[43] and then became the permanent leader in May.[44]

New political parties who made their campaign debuts in this election included the Alba Party, led by former Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond.[45] The Workers Party of Britain, led by George Galloway, also took part in the campaign but did not gain any seats and their sole MP, Galloway, lost his seat.[46]

Changes to the composition of the House of Commons before the election[edit]

This table relates to the composition of the House of Commons at the 2019 general election and its dissolution on 30 May 2024 and summarises the changes in party affiliation that took place during the 2019–2024 Parliament.

| Affiliation | Members | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elected in 2019[47] | At dissolution in 2024[48][49][50][f] | Difference | ||

| Conservative | 365 | 344 | ||

| Labour[g] | 202 | 205 | ||

| SNP | 48 | 43 | ||

| Liberal Democrats | 11 | 15 | ||

| DUP | 8 | 7 | ||

| Sinn Féin | 7 | 7 | ||

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 3 | ||

| SDLP | 2 | 2 | ||

| Alba | Yet to exist | 2[h] | ||

| Green (E&W) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Alliance (NI) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Workers Party | Yet to exist | 1 | ||

| Reform UK[i] | 0 | 1 | ||

| Speaker | 1 | 1 | ||

| Independent | 0 | 17[j] | ||

| Vacant | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 650 | 650 | ||

| Effective total voting[k] | 639 | 638 | ||

| Majority | 87 | 44[57] | ||

For full details of changes during the 2019–2024 Parliament, see By-elections and Defections, suspensions and resignations.

Date of the election[edit]

Originally the next election was scheduled to take place on 2 May 2024 under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011.[m] At the 2019 general election, in which the Conservatives won a majority of 80 seats, the party's manifesto contained a commitment to repeal the Fixed-term Parliaments Act.[59] In December 2020, the government duly published a draft Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (Repeal) Bill, later retitled the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act 2022.[60][61] This entered into force on 24 March 2022. Thus, the prime minister can again request the monarch to dissolve Parliament and call an early election with 25 working days' notice. Section 4 of the Act provided: "If it has not been dissolved earlier, a Parliament dissolves at the beginning of the day that is the fifth anniversary of the day on which it first met". The Electoral Commission confirmed that the 2019 Parliament would, therefore, have to be dissolved, at the latest, by 17 December 2024, and that the next general election had to take place no later than 28 January 2025.[62][63]

With no election date fixed in law, there was speculation as to when the prime minister, Rishi Sunak, would call an election. On 18 December 2023, Sunak told journalists that the election would take place in 2024 rather than January 2025.[64] On 4 January, he first suggested the general election would probably be in the second half of 2024.[65] Throughout 2024, political commentators and MPs expected the election to be held in the autumn.[66][67][68] On 22 May 2024, following much speculation through the day (including being asked about it by Stephen Flynn at Prime Minister's Questions),[69][70][71] Sunak officially announced the election would be held on 4 July with the dissolution of the Parliament on 30 May.[72]

The deadline for candidate nominations was 7 June 2024, with political campaigning for four weeks until polling day on 4 July. On the day of the election, polling stations across the country were open from 7 am, and closed at 10 pm. The date chosen for the 2024 general election made it the first to be held in July since the 1945 general election almost exactly seventy-nine years earlier. A total of 4,515 candidates were nominated, more than in any previous general election.[73]

Timetable[edit]

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 22 May | Prime Minister Rishi Sunak requests a dissolution of parliament from King Charles III and announces the date of polling day for the general election as 4 July. |

| 24 May | Last sitting day of business. Parliament prorogued. |

| 25 May | Beginning of pre-election period (also known as purdah).[76] |

| 30 May | Dissolution of parliament and official start of the campaign. Royal Proclamation issued dissolving the 2019 Parliament, summoning the 2024 Parliament and setting the date for its first meeting.[77] |

| 7 June | Nominations of candidates close (4 pm). Publication of statement of persons nominated, including notice of poll and situation of polling stations (5 pm). |

| 13 June | Deadline to register to vote at 11:59 pm in Northern Ireland. |

| 18 June | Deadline to register to vote at 11:59 pm in Great Britain. |

| 19 June | Deadline to apply for a postal vote. |

| 26 June | Deadline to register for a proxy vote at 5 pm. Exemptions applied for emergencies. |

| 4 July | Polling Day – polls open from 7 am to 10 pm. |

| 4–5 July | Results announced in 648 of 650 constituencies. |

| 5 July | Labour wins election with 170-seat majority. End of pre-election period (also known as purdah). |

| 6 July | Results announced for final two undeclared seats, following recounts. |

| 9 July | First meeting of the new Parliament of the United Kingdom for the formal election of Speaker of the House of Commons. Sir Lindsay Hoyle is re-elected unopposed and calls on Sir Keir Starmer and Sunak to speak as Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition respectively for the first time. |

| 9–11 July | MPs taking their seat are sworn in by oath or allegiance. |

| 17 July | State Opening of Parliament and King's Speech. |

Electoral system[edit]

General elections in the United Kingdom are organised using first-past-the-post voting. The Conservative Party, which won a majority at the 2019 general election, included pledges in its manifesto to remove the 15-year limit on voting for British citizens living abroad, and to introduce a voter identification requirement in Great Britain.[78] These changes were included in the Elections Act 2022.[79]

Boundary reviews[edit]

The Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, which proposed reducing the number of constituencies from 650 to 600, commenced in 2011 but temporarily stopped in January 2013. Following the 2015 general election, each of the four parliamentary boundary commissions of the United Kingdom recommenced their review process in April 2016.[80][81][82] The four commissions submitted their final recommendations to the Secretary of State on 5 September 2018[83][84] and made their reports public a week later.[85][86][87][83] However, the proposals were never put forward for approval before the calling of the general election held on 12 December 2019, and in December 2020 the reviews were formally abandoned under the Schedule to the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 2020.[88] A projection by psephologists Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher of how the 2017 votes would have translated to seats under the 2018 boundaries suggested the changes would have been beneficial to the Conservatives and detrimental to Labour.[89][90]

In March 2020, Cabinet Office minister Chloe Smith confirmed that the 2023 Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies would be based on retaining 650 seats.[91][92] The previous relevant legislation was amended by the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 2020[93] and the four boundary commissions formally launched their 2023 reviews on 5 January 2021.[94][95][96][97] They were required to issue their final reports prior to 1 July 2023.[88] Once the reports had been laid before Parliament, Orders in Council giving effect to the final proposals had to be made within four months, unless "there are exceptional circumstances". Prior to the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 2020, boundary changes could not be implemented until they were approved by both Houses of Parliament. The boundary changes were approved at a meeting of the Privy Council on 15 November 2023[98] and came into force on 29 November 2023,[99] meaning that the election is being contested on these new boundaries.[100]

Notional 2019 results[edit]

The election was contested under new constituency boundaries established by the 2023 Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies. Consequently, media outlets reported seat gains and losses as compared to notional results. These are the results if all votes cast in 2019 were unchanged but regrouped by new constituency boundaries.[101] Notional results in the UK are always estimated, usually with the assistance of local election results, because vote counts at parliamentary elections in the UK do not yield figures at any level more specific than that of the whole constituency.[102]

In England, seats were redistributed towards Southern England, away from Northern England, due to the different rates of population growth. North West England and North East England lost two seats each whereas South East England gained seven seats, and South West England gained three seats.[103] Based on historical voting patterns, this was expected to help the Conservatives. Based on these new boundaries, different parties would have won several constituencies with unchanged names but changed boundaries in 2019. For example, the Conservatives would have won Wirral West and Leeds North West instead of the Labour Party, but Labour would have won Pudsey and Heywood & Middleton instead of the Conservatives. Westmorland and Lonsdale, the constituency represented by former Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron, was notionally a Conservative seat.[104][105]

In Scotland, 57 MPs were elected, down from the 59 in 2019,[106] with the following notional partisan composition of Scotland's parliamentary delegation. The Scottish National Party would have remained steady on 48 seats despite two of its constituencies being dissolved. The Scottish Conservatives' seat count of six would likewise remained unchanged. Scottish Labour would have retained Edinburgh South, the sole constituency they won in 2019. Had the 2019 general election occurred with the new boundaries in effect, the Scottish Liberal Democrats would have only won two seats (Edinburgh West and Orkney and Shetland), instead of the four they did win that year, as the expanded electorates in the other two would overcome their slender majorities.[107]

Under the new boundaries, Wales lost eight seats, electing 32 MPs instead of the 40 it elected in 2019. Welsh Labour would have won 18 instead of the 22 MPs it elected in 2019, and the Welsh Conservatives 12 instead of 14. Due to the abolition and merging of rural constituencies in West Wales, Plaid Cymru would have only won two seats instead of four. Nonetheless, the boundary changes were expected to cause difficulty for the Conservatives as more pro-Labour areas are added to some of their safest seats.[108]

In Northern Ireland, the notional results are identical to the actual results of the 2019 general election in Northern Ireland.[109]

| Party | 2019 MPs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | Notional | Difference | ||

| Conservative | 365 | 372 | ||

| Labour | 202 | 200 | ||

| SNP | 48 | 48 | ||

| Liberal Democrats | 11 | 8 | ||

| DUP | 8 | 8 | ||

| Sinn Féin | 7 | 7 | ||

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 2 | ||

| SDLP | 2 | 2 | ||

| Green (E&W) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Alliance | 1 | 1 | ||

| Speaker | 1 | 1 | ||

Campaign[edit]

Overview[edit]

Labour entered the election with a large lead over the Conservatives in opinion polls, and the potential scale of the party's victory was a topic of discussion during the campaign period.[9][10] The economy, healthcare, education, infrastructure development, immigration, housing and energy were main campaign topics. The Conservative campaign, as well as Sunak's handling of it, was widely panned by commentators, focusing primarily on attacks towards Labour over alleged tax plans including a disproven claim that Labour would cost households £2000 more in tax.[110][111]

Starmer led a positive campaign for the Labour Party, using the word "change" as his campaign slogan and offered voters the chance to "turn the page" by voting Labour.[112] The Liberal Democrat campaign led by Ed Davey was dominated by his campaign stunts, which were used to bring attention to campaign topics.[113][114] When asked about these stunts, Davey said: "Politicians need to take the concerns and interests of voters seriously but I'm not sure they need to take themselves seriously all the time and I'm quite happy to have some fun."[115] Party manifesto and fiscal spending plans were independently analysed by the Institute for Fiscal Studies[116] and their environmental policies were assessed by Friends of the Earth.[117]

Announcement[edit]

On the afternoon of 22 May 2024, the prime minister Rishi Sunak announced that he had asked the King to call a general election for 4 July 2024, surprising his own MPs.[118] Though Sunak had the option to wait until December 2024 to call the election, he said that he decided on the date because he believed that the economy was improving, and that "falling inflation and net migration figures would reinforce the Conservative Party's election message of 'sticking to the plan'".[119] The calling of the election was welcomed by all major parties.[120]

Sunak's announcement took place during heavy rain at a lectern outside 10 Downing Street, without the use of any shelter from the rain.[121] The D:Ream song "Things Can Only Get Better" (frequently used by the Labour Party in its successful 1997 general election campaign) was being played loudly in the background by the political activist Steve Bray as Sunak announced the date of the general election.[122] This led to the song reaching number two on UK's iTunes Charts.[123][124]

22–29 May[edit]

At the beginning of the campaign, Labour had a significant lead in polling over the Conservatives.[28][125] Polling also showed Labour doing well against the Scottish National Party (SNP) in Scotland.[126] When visiting Windermere, Davey fell off a paddleboard, while campaigning to highlight the issue of sewage discharges into rivers and lakes.[127] A couple of days later, Davey won media attention when going down a Slip 'N Slide, while drawing attention to deteriorating mental health among children.[115]

On 23 May, Sunak said that before the election there would be no flights to Rwanda for those seeking asylum.[128] Immigration figures were published for 2023 showing immigration remained at historically high levels, but had fallen compared to 2022.[129] Nigel Farage initially said that he would not stand as a candidate in the election, while his party Reform UK said it would stand candidates in 630 seats across England, Scotland and Wales.[130] Farage later announced on 3 June that, contrary to his statement earlier in the campaign, he would stand for Parliament in Clacton, and that he had resumed leadership of Reform UK, taking over from Richard Tice, who remained the party's chairman. Farage also predicted that Labour would win the election.[131] Davey released the Liberal Democrat campaign in Cheltenham in Gloucestershire.[132] The SNP campaign launch the same day was overshadowed over a dispute around leader John Swinney's support for Michael Matheson and developments in Operation Branchform.[133] Keir Starmer launched the Labour Party campaign in Gillingham at the Priestfield Stadium, home of Gillingham Football Club.[134]

On 24 May, the Conservatives proposed setting up a Royal Commission to consider a form of mandatory national service.[135] It would be made up of two streams for 18-year-olds to choose from, either 'community volunteering' by volunteering with organisations such as the NHS, fire service, ambulance, search and rescue, and critical local infrastructure, or 'military training' in areas like logistics and cyber security.[136] Former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn announced on 24 May he was running as an independent in Islington North against a Labour candidate, and was thus expelled from the party.[137]

On 27 May, Starmer made a keynote speech on security and other issues.[138][139] On 28 May, the Conservatives pledged a "Triple Lock Plus" where the personal income tax allowance for pensioners would always stay higher than the state pension.[140][141] Davey went paddleboarding on Lake Windermere in the marginal constituency of Westmorland and Lonsdale, highlighting the release of sewage in waterways.[142] He pledged to abolish Ofwat and introduce a new water regulator to tackle the situation, in addition to proposing a ban on bonuses for chief executives of water companies.[143] Starmer was in West Sussex and emphasised his small town roots in his first big campaign speech.[144]

On 29 May, Labour's Wes Streeting promised a 18-week NHS waiting target within five years of a Labour government.[145] Labour also pledged to double number of NHS scanners in England. On the same day Starmer denied that Diane Abbott had been blocked as a candidate amid differing reports.[146] Abbott had been elected as a Labour MP, but had been suspended from the parliamentary party for a brief period. There was controversy about further Labour Party candidate selections, with several candidates on the left of the party being excluded.[147] Abbott said she had been barred from standing as a Labour Party candidate at the election, but Starmer later said she would be "free" to stand as a Labour candidate.[148]

30 May – 5 June[edit]

On 30 May, both the Conservatives and Labour ruled out any rise in value-added tax.[149] The SNPs Màiri McAllan claimed that only the SNP offered Scotland a route back into the European Union, making Pro-Europeanism part of the party's campaign.[150] Reform UK proposed an immigration tax on British firms who employ foreign workers.[151] Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay launched the Green Party of England and Wales campaign in Bristol.[152] Rhun ap Iorwerth launched the Plaid Cymru campaign in Bangor.[153] George Galloway launched the Workers Party of Britain campaign in Ashton-under-Lyne.[154]

On 31 May, the Conservatives announced new "pride in places" pledges, including new rules to tackle anti-social behaviour, rolling out the hot-spot policing programme to more areas, and more town regeneration projects. The Conservatives also unveiled plans for fly-tippers to get points on their driving licences and other new measures to protect the environment.[155]

On 2 June, Labour pledged to reduce record high legal immigration to the United Kingdom by improving training for British workers.[156] Net migration to the UK was 685,000 in 2023.[157][158]

On 3 June, Sunak pledged to tackle what he called the "confusion" over the legal definition of sex by proposing amending the Equality Act.[159] Labour focused on national security, with Starmer reaffirming his commitment to a "nuclear deterrent triple lock", including building four new nuclear submarines.[131] A YouGov poll conducted on the same day put Labour on course for the party's biggest election victory in history, beating Tony Blair's 1997 landslide.[160]

On 4 June, Farage launched his campaign in Clacton.[161] He predicted the previous day that Reform UK would be the Official Opposition following the election as opposed to the Conservatives, saying that the Conservatives are incapable of being the Opposition due to "spending most of the last five years fighting each other rather than fighting for the interests of this country".[162]

6–12 June[edit]

On 6 June, the Green Party announced plans to invest an extra £50 billion a year for the NHS by raising taxes on the top 1% of earners.[163] Social care has been a campaign issue.[164] The Conservatives announced a policy on expanding child benefit for higher-earners.[165] Labour also announced communities will be given powers to transform derelict areas into parks and green spaces. Labour's countryside protection plan would also include the planting new national forests, taskforces for tree-planting and flood resilience, new river pathways, and a commitment to revive nature.[166] Green spaces would be a requirement in the development of new housing and town plans.[167]

Both Sunak and Starmer attended D-Day commemorations in Normandy on 6 June, the 80th anniversary of Operation Neptune. Sunak was widely criticised for leaving events early to do an interview with ITV, including by veterans.[168] Starmer met with Volodymyr Zelenskyy and King Charles III during the D-Day commemorations, and said that Sunak "has to answer for his actions".[169][170] Sunak apologised the next day[171] and apologised again on 10 June.[172] He made a third apology on 12 June.[173]

Farage was among those critical of Sunak over his leaving the D-Day events,[174] saying on 7 June that Sunak did not understand "our culture". Conservative and Labour politicians criticised these words as being a racist attack on Sunak, which Farage denied.[175] Douglas Ross announced he would stand down as the leader of the Scottish Conservatives after the election.[176]

On 10 June, Labour pledged 100,000 new childcare places and more than 3,000 new nurseries as part of its childcare plan.[177] It also announced its Child Health Action Plan, which included providing every school with a qualified mental health counselor, boosting preventative mental health services, transforming NHS dentistry, legislating for a progressive ban on smoking, banning junk food advertising to children, and banning energy drinks for under 16s.[178][179]

The Liberal Democrat manifesto For a Fair Deal was released on 10 June,[180][181] which included commitments on free personal care in England,[182] investment in the NHS including more GPs, increased funding for education and childcare (including a tutoring guarantee for children from low-income families), increased funding for public services, tax reforms, reaching net zero by 2045 (5 years before the current government target of 2050), investing in green infrastructure, innovation, training and skills across the UK to boost economic growth, and removing the two-child limit on tax and benefits.[183] The Liberal Democrats also offered a lifelong skills grant, giving adults £5,000 to spend on improving their skills.[184] The party wants electoral reform, and pledged to introduce proportional representation for electing MPs, and local councillors in England, and cap donations to political parties.[185][186]

Sunak released the Conservative manifesto Clear Plan. Bold Action. Secure Future. on 11 June, addressing the economy, taxes, welfare, expanding free childcare, education, healthcare, environment, energy, transport, community, and crime.[187][188] They pledged to lower taxes, increase education and NHS spending, deliver 92,000 more nurses and 28,000 more doctors, introduce a new model of National Service, continue to expand apprenticeships and vocational training, simplify the planning system to speed up infrastructure projects (digital, transport and energy), and to treble Britain's offshore wind capacity and support solar energy. The manifesto includes a pledge to abolish Stamp Duty on homes worth up to £425,000 for first time buyers and expand the Help to Buy scheme.[189] The Conservatives also pledged a recruitment of 8,000 new police officers and a rollout of facial recognition technology.[190] Much of what has been proposed is already incorporated in the 2024 budget.[191][192][193]

Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay released the Green Party's manifesto Real Hope. Real Change. on 12 June, which pledged more taxes on the highest earners, generating £70 billion a year to help tackle climate change and the NHS. They also pledged increased spending for public services, free personal care in England, renationalisation of railway, water and energy, a green society, a wealth tax, a carbon tax, and a windfall tax on the profit of banks.[194][195] The manifesto promises quicker access to NHS dentistry and GPs and reductions in the hospital waiting list. They would also reach net zero by 2040 and introduce rent controls.[196][197]

On 12 June, Conservative minister Grant Shapps said in a radio interview that voters should support the Conservatives so as to prevent Labour winning "a super-majority", meaning a large majority (the UK Parliament does not have any formal supermajority rules). This was interpreted by journalists as a possible and surprising admission of defeat.[198][199][200] It paralleled social media advertising by the Conservatives that also focused on urging votes not to give Starmer a large majority.[201]

13–19 June[edit]

On 13 June, Starmer released the Labour Party manifesto Change, which focused on economic growth, planning system reforms, infrastructure, clean energy, healthcare, education, childcare, crime, and strengthening workers' rights.[202][203] It pledged a new publicly owned energy company (Great British Energy) and National Wealth Fund, a ''Green Prosperity Plan", rebuilding the NHS and reducing patient waiting times, free breakfast clubs in primary schools, investing in green infrastructure, innovation, training and skills across the UK to boost economic growth, and renationalisation of the railway network (Great British Railways).[204] It includes wealth creation and "pro-business and pro-worker" policies.[205] The manifesto also pledged to give votes to 16-year olds, reform the House of Lords, and to tax private schools, with money generated going into improving state education.[206][207][208] The party guaranteed giving all areas of England devolution powers, in areas such as integrated transport, planning, skills, and health.[209][210]

On 17 June, Farage and Tice released the Reform UK manifesto, which they called a "contract" (Our Contract with You). It pledged to lower taxes, lower immigration, increase funding for public services, reform the NHS and decrease its waiting lists down to zero, bring utilities and critical national infrastructure under 50% public ownership (the other 50% owned by pension funds), replace the House of Lords with a more democratic second chamber, and to replace first-past-the-post voting with a system of proportional representation.[211] It also pledged to accelerate transport infrastructure in coastal regions, Wales, the North, and the Midlands.[212][213] The party also wants to freeze non-essential immigration and recruit 40,000 new police officers.[214] Reform UK are the only major party to oppose the current net zero target made by the government.[215] Instead, it pledged to support the environment with more tree planting, more recycling and less single-use plastics.[216][217][218] Farage predicted Labour would win the election, but said he was planning to campaign for the next election.[219]

Labour's Rachel Reeves claimed Labour's green plans would create over 650,000 jobs.[220][221] The Liberal Democrats offered more cost-of-living help for rural communities.[222] Davey highlighted his manifesto pledge to build 380,000 new homes a year, 150,000 of which would be social homes.[223] On 18 June, Labour pledged hundreds of new banking hubs, to ''breathe life'' into high streets.[224][225] Labour also promised a large increase of renewable energy jobs, backed by new green apprenticeships.[226]

On 19 June, both the SNP and Sinn Féin released their manifestos. Swinney said a vote for his party would "intensify" the pressure to secure a second Scottish independence referendum, with other pledges in the SNP manifesto including boosting NHS funding, scrapping the two-child limit on benefits, calling for an immediate ceasefire in the Gaza Strip, scrapping the Trident defence programme, re-joining the European Union, transitioning to a green economy attracting more foreign migrants,[227] tackling drug deaths and devolving broadcasting powers.[228] The Sinn Féin manifesto called for greater devolution to Northern Ireland and for the UK and Irish governments to set a date for a referendum on the unification of Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland.[229]

Galloway released the Workers Party manifesto, with promises to improve "poverty pay" and provide more social housing.[230] It pledged the renationalisation of utility companies, free school meals for all children without means testing, free adult education, and to hold a referendum on the continued existence of the monarchy and proportional representation for elections.[231]

David TC Davies, the Secretary of State for Wales, told a BBC interview the polls were "clearly pointing at a large Labour majority", but added that he believed there was "no great optimism" from voters.[232] A potentially large Labour majority was also acknowledged by Jeremy Hunt, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Mel Stride, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions.[233] Alison McGarry, the Labour chair of Islington North, resigned from the Labour Party after being spotted campaigning for Corbyn; she resigned rather than face expulsion for breaking the party's rules on campaigning for a rival candidate.[234]

20–26 June[edit]

On 20 June, the parties focused on housing. Labour pledged action to protect renters with new legal protections for tenants. It would immediately ban Section 21 "no-fault" evictions, as part of plans to reform the private rented sector in England.[235] Labour also pledged to reform planning laws and build 1.5 million homes to spread homeownership.[236] The Conservatives offered stronger legal protections for tenants, including banning Section 21 "no-fault" evictions.[237] They said they would build 1.6 million new homes, prioritising brownfield development, while protecting the countryside.[238] The Liberal Democrats offered more protections for tenants, additional social housing, and more garden cities.[239][240]

Also on 20 June, the Alliance Party in Northern Ireland launched their manifesto.[241] Its core policies include reforming the political institutions, dedicated funding for integrated education, a Green New Deal to decarbonise Northern Ireland's economy, childcare reforms, and lowering the voting age to 16.[242]

On 21 June, in a BBC Panorama interview with Nick Robinson, Farage repeated comments he had made previously stating that the West and NATO provoked Russia's invasion of Ukraine. He was criticised for this by Sunak and Starmer.[243] He also stated that Reform UK would lower the tax burden to encourage people into work.[244] Farage stated in another interview that he would remove university tuition fees if he won power for those studying science, technology, engineering, medicine or maths. Reform UK have already pledged to scrap interest on student loans and to extend the loan capital repayment periods to 45 years.[245] Farage also declared his ambition for Reform UK to replace the Conservatives as the biggest right-wing party in Parliament.[246]

The Conservatives pledged a review of licensing laws and planning rules aimed at boosting pubs, restaurants and music venues.[247] Labour framed its 10-year science and R&D budget plans as part of its industrial strategy, with an aim of boosting workforce and regional development.[248][249] Labour and the Liberal Democrats also focused on water pollution and improving England's water quality.[250][251] Labour pledged to put failing water companies who do not meet ''high environmental standards'' under special measures, give regulators new powers to block the payment of bonuses to executives who pollute waterways, and criminal charges against persistent law breakers. They also ensured independent monitoring of every outlet.[252]

On 24 June, Labour focused on NHS dentistry and health.[253] Labour also pledged to hold a knife crime summit every year and halve incidents within a decade.[254] The Greens pledged to end 'dental deserts' with £3 billion for new NHS contracts.[255]

The Liberal Democrats launched a mini-manifesto for carers.[256] It pledged to establish an independent living taskforce to help people live independently in their own homes, a new care worker's minimum wage to raise their pay by £2 an hour, and a new National Care Agency. Sunak released the Scottish Conservatives' manifesto.[257] Starmer discussed a proposed Football Governance Bill,[258] which will establish the new Independent Football Regulator.[259] The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats have also committed to introducing an Independent Football Regulator.[260] The Liberal Democrats pledged to establish a series of "creative enterprise zones" across the UK to regenerate cultural output.[261]

On 26 June, Alex Salmond released the Alba Party manifesto. It pledged to increase funding for public services, increase NHS staffing, provide an annual £500 payment to households receiving the council tax reduction at a cost of £250 million, increase the Scottish Child Payment, reducing fuel bills, a new Scottish clean energy public company, and Scottish Independence.[262]

Starmer pledged GP reforms, including the training of thousands more GPs, updating the NHS App, and bringing back the 'family doctor'.[263] Labour would also trial new "neighbourhood health centres".[264] The Social Democratic and Labour Party also launched their manifesto on 26 June in Northern Ireland.[265] It pledged a 'Marshall Plan' to tackle health, institutional reform, stronger environmental protection with an independent Environmental Protection Agency, and improving NI's financial settlement.[266]

27 June – 4 July[edit]

On 27 June, Labour pledged to reform careers advice and work experience in schools for one million pupils, committing to deliver two weeks' worth of quality work experience for every young person, and recruit more than thousands of new careers advisers.[267] This is part of the party's wider plan to establish a "youth guarantee" of access to training, an apprenticeship or support to find work for all 18 to 21-year-olds.[268][269]

On 27 June, an undercover Channel 4 journalist secretly recorded members of Farage's campaign team using offensive racial, Islamophobic and homophobic language, also suggesting refugees should be used as "target practice".[270] In a statement, Farage said that he was "dismayed" at the "reprehensible" language.[271] Tice said that racist comments were "inappropriate".[270] Farage later accused Channel 4 of a "set-up", stating that one of the canvassers, Andrew Parker, had been an actor. Farage stated that Parker had been "acting from the moment he came into the office", and cited video of Parker performing "rough-speaking" from his acting website. Channel 4 denied that Parker was known to them prior to the report.[272] Regarding other members of his campaign team, Farage stated that the individuals in question had "watched England play football, they were in the pub, they were drunk, it was crass."[273]

On 29 June, the Liberal Democrats called for an 'emergency NHS budget' to hire more GPs.[274] Starmer hosted a major campaign rally,[275] and stated in The Guardian "if you vote Labour on Thursday, the work of change begins. We will launch a new national mission to create wealth in every community. We’ll get to work on repairing our public services with an immediate cash injection, alongside urgent reforms. And we will break with recent years by always putting country before party".[275][276]

The Greens announced a 'Charter for Small Business', which pledged £2 billion per year in grant funding for local authorities, regional mutual banks for investment in decarbonisation and local economic sustainability, and increasing annual public subsidies for rail and bus travel to £10 billion.[277][278] They also pledged free bus travel for under-18s.[279] The Northern Ireland Conservatives also launched their manifesto.[280] On 30 June, the Liberal Democrats pledged to double funding for Bereavement Support Payments, and to spend £440 million a year on support for bereaved families.[281]

On 2 July, the Greens announced its £8 billion education package would include scrapping tuition fees, providing free school meals for all children, a qualified counsellor in every school and college, and new special needs provision. They also want to end formal testing in primary and secondary schools with a system of continuous assessment.[282] Former prime minister Boris Johnson campaigned for the Conservatives.[283] On 3 July, the political parties made their closing arguments on the last day of campaigning, with Sunak stating he would "take full responsibility" for the result.[284] At the end of the campaign, Labour maintained their significant lead in polling over the Conservatives, and had endorsements from celebrities, including Elton John.[285]

On 4 July, less than an hour before polls closed, Sunak's government announced the 2024 Dissolution Honours, with life peerages being given to 19 people, including former prime minister Theresa May and Cass Review author Hilary Cass.[286][287]

Debates and interviews[edit]

Debates[edit]

| ← 2019 debates | 2024 |

|---|

Rishi Sunak challenged Keir Starmer to six televised debates.[288] Starmer announced that he would not agree to such a proposal, and offered two head-to-head debates—one shown on the BBC, and one shown on ITV; a spokesperson said both networks would offer the greatest audience, and the prospect of any debates on smaller channels would be rejected as it would not be a "valuable use of campaign time". Ed Davey declared his wish to be included in "any televised debates", although he would ultimately only be featured in one debate.[289]

On 29 May, it was announced that the first leaders' debate would be hosted by ITV News and titled "Sunak v Starmer: The ITV Debate" with Julie Etchingham as moderator, on 4 June.[290] Key topics were the cost of living crisis, the National Health Service (NHS), young people, immigration and tax policy.[291] Sunak said that Labour would cost households £2000 more in tax, which Starmer denied. Sunak said this figure was calculated by "independent Treasury officials". Fact checkers disputed the sum, stating it was based on assumptions made by political appointees and that the figure was over a 4-year period. On 5 June, the BBC reported that James Bowler, the Treasury permanent secretary, wrote that "civil servants were not involved in the [...] calculation of the total figure used" and that "any costings derived from other sources or produced by other organisations should not be presented as having been produced by the Civil Service".[292] The Office for Statistics Regulation also criticised the claim on the grounds that it was presented without the listener knowing it was a sum over 4 years.[293] A YouGov snap poll after the debate indicated that 46% of debate viewers thought Sunak had performed better, and 45% believed Starmer had performed better.[294] A Savanta poll published the next day favoured Starmer 44% to Sunak 39%.[295] The debate was watched by 5.37 million viewers, making it the most-viewed programme of the week.[296]

An STV debate hosted by Colin Mackay took place on 3 June, which included Douglas Ross, Anas Sarwar, John Swinney and Alex Cole-Hamilton.[297] Another debate between these leaders (also including Lorna Slater) took place on 11 June, on BBC Scotland, hosted by Stephen Jardine. A BBC debate hosted by Mishal Husain took place on 7 June, which included Nigel Farage, Carla Denyer, Rhun ap Iorwerth, Daisy Cooper, Stephen Flynn, Angela Rayner and Penny Mordaunt.[298] The debate included exchanges between Mordaunt and Rayner over tax, and all the attendees criticised Sunak leaving the D-Day events early; Farage called Sunak's actions "disgraceful" and said veterans had been deserted, Cooper said it was "politically shameful" and Mordaunt said Sunak's choice to leave prematurely had been "completely wrong".[299][300] After the seven-way debate, a snap poll found that viewers considered Farage had won, followed by Rayner, but that Flynn, Denyer and Cooper scored best on doing a good job.[301] Another debate between these leaders took place on 13 June, with Julie Etchingham as moderator.[302][303]

On 12 June Sky News hosted a leaders' event in Grimsby hosted by Beth Rigby, including Starmer and Sunak, where they took questions from both Rigby and the audience.[304] The debate covered various topics, including the NHS, the economy, immigration, housing and their future plans in government. Starmer started the event by saying he was putting the country ahead of his party, bringing Labour "back into the service of working people". He went on to attack the Conservatives on tax policy, saying that "the Tories are in no position to lecture anyone about tax rises".[305][306] 64% of those questioned by YouGov immediately following the debate said that Starmer had performed better, compared to 36% who said Sunak had performed better.[307]

Channel 4 News hosted a debate on 18 June with all seven of the main parties focusing solely on the issues of immigration and law and order.[308] On 24 June, a The Sun/Talk debate hosted by Harry Cole titled Never Mind the Ballots: Election Showdown was attended by Sunak and Starmer.[n] Other BBC debates included three Question Time specials, two hosted by Fiona Bruce on 20 and 28 June, and one hosted by Bethan Rhys Roberts on 24 June. The first of the two hosted by Bruce featured four separate half-hour question and answer sessions with Sunak, Starmer, Davey and Swinney; the second of the two hosted by Bruce featured the same format with Ramsay and Farage; the programme hosted by Rhys Roberts featured the same format with ap Iorwerth. There was a BBC Cymru Wales debate on 21 June;[309] and a debate between Sunak and Starmer hosted by Husain took place on 26 June.[310] There was also a BBC debate on 27 June involving the five largest Northern Irish political parties.[309]

| 2024 United Kingdom general election debates in Northern Ireland | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Organiser | Host | Format | Venue | Viewing figures (millions) |

| ||||||||||||

| DUP | Sinn Féin | SDLP | UUP | Alliance | ||||||||||||||

| 23 June[326] | UTV | Vicki Hawthorne | Debate | UTV HQ, City Quays 2, Belfast[327] | TBA | P Robinson | S Finucane | P Eastwood | S Butler | P Long | ||||||||

| 27 June[309] | BBC Northern Ireland | Tara Mills | Debate | Broadcasting House, Belfast | TBA | P Robinson | S Hazzard | P Eastwood | S Butler | P Long | ||||||||

Interviews[edit]

In addition to the debates, the BBC and ITV broadcast programmes in which the leaders of the main parties were interviewed at length.[328][329] Sunak's Tonight interview with Paul Brand drew substantial coverage in the week prior to broadcast, as Sunak controversially departed the D-Day commemorations early to attend. It was later revealed that the interview slot had been chosen by Sunak and his team from a range of options offered by ITN.[330]

Endorsements[edit]

Newspapers, organisations, and individuals endorsed parties or individual candidates for the election.

Candidates[edit]

There were 4515 candidates standing, which constitutes a record number, with a mean of 6.95 candidates per constituency. No seat had fewer than five people contesting it; Rishi Sunak's Richmond and Northallerton seat had the most candidates, with thirteen.[331]

MPs who stood down at the election included the former prime minister Theresa May, the former cabinet ministers Sajid Javid, Dominic Raab, Matt Hancock, Ben Wallace, Nadhim Zahawi, Kwasi Kwarteng, and Michael Gove, the long-serving Labour MPs Harriet Harman and Margaret Beckett, and the former Green Party leader and co-leader Caroline Lucas, who was the first – and until this election the only – Green Party MP.[332]

In March 2022, Labour abandoned all-women shortlists, citing legal advice that continuing to use them for choosing parliamentary candidates would be an unlawful practice under the Equality Act 2010, since the majority of Labour MPs were now women.[333]

In March 2024, Reform UK announced an electoral pact with the Northern Irish unionist party TUV.[334][335] The TUV applied to run candidates as "TUV/Reform UK" on ballot papers, but this was rejected by the Electoral Office.[336] Nigel Farage unilaterally ended this deal by endorsing two competing candidates from the Democratic Unionist Party on 10 June.[337] Reform UK also announced a pact with the Social Democratic Party (SDP), a minor socially conservative party, in some seats.[338]

The below table shows all parties standing in at least 14 seats.

There are additionally

- 37 other parties with more than one candidate standing,

- 36 candidates who are the only candidates of the group they are representing

- 459 independent candidates

- the Speaker.

A more complete list can be found here.

Opinion polling[edit]

| Opinion polling for UK general elections |

|---|

| 2010 election |

| Opinion polls |

| 2015 election |

| Opinion polls • Leadership approval |

| 2017 election |

| Opinion polls • Leadership approval |

| 2019 election |

| Opinion polls • Leadership approval |

| 2024 election |

| Opinion polls • Leadership approval |

Discussion around the campaign was focused on the prospect of a change in government, as the opposition Labour Party led by Keir Starmer maintained significant leads in opinion polling over the governing Conservative Party led by the prime minister Rishi Sunak, with one in five voters voting tactically.[341] Projections four weeks before the vote indicated a landslide victory for Labour that surpassed the one achieved by Tony Blair at the 1997 United Kingdom general election, while comparisons were made in the media to the 1993 Canadian federal election due to the prospect of a potential Conservative wipeout.[9][10] A YouGov poll conducted four weeks before the vote suggested that Labour was on course for the party's biggest election victory in history, beating Blair's 1997 landslide. The poll indicated Labour could win 422 seats, while the Conservatives were projected to win 140 seats.[342]

Halfway through the campaign, psephologist John Curtice summarised the polls as having shown little change in the first two weeks of the campaign but that they had then shown some clear shifts. Specifically, both the Conservatives and Labour had shown a decline of a few percentage points, leaving the gap between them unchanged, while Reform UK and the Liberal Democrats had both shown an increase, with one YouGov poll published 13 June attracting attention for showing Reform UK one point above the Conservatives.[343][344]

Graphical summaries[edit]

Projections[edit]

"Others" figure includes the Speaker as well as the various political parties in Northern Ireland unless otherwise stated.

Four weeks before the vote[edit]

| Source | Date | Con | Lab | Lib Dems | SNP | Plaid | Green | Reform | Others | Overall result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Economist[345][n 2] | 7 June | 182 | 394 | 22 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 19 | Labour majority 138 |

| Electoral Calculus[346] | 7 June | 75 | 474 | 61 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 19 | Labour majority 298 |

| ElectionMapsUK[347] | 10 June | 101 | 451 | 59 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 19 | Labour majority 252 |

| Financial Times[348] | 7 June | 139 | 443 | 32 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 19 | Labour majority 236 |

| New Statesman[349][350][351] | 7 June | 86 | 455 | 65 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 19 | Labour majority 260 |

| YouGov[352] | 3 June | 140 | 422 | 48 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 19 | Labour majority 194 |

Two weeks before the vote[edit]

| Source | Date | Con | Lab | Lib Dems | SNP | Plaid | Green | Reform | Others | Overall result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Economist[353] | 20 June | 184 | 383 | 23 | 28 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 19[n 3] | Labour majority 116 |

| Electoral Calculus[354] | 21 June | 76 | 457[n 4] | 66 | 22 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | Labour majority 264 |

| Financial Times[355] | 19 June | 97 | 459 | 51 | 21 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 19[n 3] | Labour majority 268 |

| The New Statesman[356] | 20 June | 101 | 437 | 63 | 22 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 19[n 3] | Labour majority 224 |

| YouGov[357] | 19 June | 108 | 425 | 67 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 0 | Labour majority 198 |

| Ipsos[358] | 18 June | 115 | 453 | 38 | 15 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1[n 4] | Labour majority 256 |

| Savanta[359][360] | 19 June | 53 | 516 | 50 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Labour majority 380 |

| The New Statesman[361] | 22 June | 96 | 435 | 63 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 1 | Labour majority 238 |

One week before the vote[edit]

| Source | Date | Con | Lab | Lib Dems | SNP | Plaid | Green | Reform | Others | Overall result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Economist[362] | 27 June | 117 | 429 | 42 | 23 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 19[n 3] | Labour majority 208 |

| Electoral Calculus[363] | 26 June | 60 | 450[n 4] | 71 | 24 | 4 | 4 | 18 | 19[n 5] | Labour majority 250 |

| Financial Times[364] | 28 June | 91 | 459 | 64 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 19[n 3] | Labour majority 268 |

| ElectionMapsUK[365] | 27 June | 80 | 453 | 71 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 19[n 3] | Labour majority 256 |

| The New Statesman[366] | 29 June | 90 | 436 | 68 | 23 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 19[n 3] | Labour majority 222 |

| ElectionMapsUK[367] | 1 July | 81 | 453 | 69 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 19 | Labour majority 256 |

Final projections[edit]

| Source | Date | Con | Lab | Lib Dems | SNP | Plaid | Green | Reform | Others | Overall result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survation[368][n 2] | 2 July | 64 | 483 | 61 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 19 | Labour majority 316 |

| More in Common[369] | 3 July | 126 | 430 | 52 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 21 | Labour majority 210 |

| The Economist[370][n 2] | 3 July | 109 | 432 | 48 | 21 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 19 | Labour majority 214 |

| Financial Times[371] | 3 July | 98 | 447 | 63 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 19 | Labour majority 244 |

| YouGov[372][373] | 3 July | 102 | 431 | 72 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 19 | Labour majority 212 |

| New Statesman[374] | 3 July | 114 | 418 | 63 | 23 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 19 | Labour majority 186 |

| Election Maps UK[375][376] | 4 July | 101 | 432 | 68 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 19 | Labour majority 214 |

| Electoral Calculus[377] | 4 July | 78 | 453 | 67 | 19 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 20 | Labour majority 256 |

| Bunker Consulting Group[378] | 1 July | 130 | 425 | 43 | 26 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 19 | Labour majority 200 |

Exit poll[edit]

An exit poll conducted by Ipsos for the BBC, ITV, and Sky News was published at the end of voting at 22:00, predicting the number of seats for each party.[379]

| Parties | Seats | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour Party | 410 | ||

| Conservative Party | 131 | ||

| Liberal Democrats | 61 | ||

| Reform UK | 13 | ||

| Scottish National Party | 10 | ||

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | ||

| Green Party | 2 | ||

| Others | 19 | ||

| Labour majority of 170 | |||

Results[edit]

Voting closed at 22:00, which was followed by an exit poll. The first seat, Houghton and Sunderland South, was declared at 23:15 with Bridget Phillipson winning for Labour.[380][381] Inverness, Skye and West Ross-shire was the last seat to declare, due to multiple recounts after the election, with Angus MacDonald winning for the Liberal Democrats on Saturday afternoon.[382]

Summary of seats returned[edit]

| Affiliate | Leader | MPs | Votes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Of total | Of total | |||||||

| Labour Party | Keir Starmer | 411[w] | 63.2% | 9,704,655 | 33.7% | |||

| Conservative Party | Rishi Sunak | 121 | 18.6% | 6,827,311 | 23.7% | |||

| Liberal Democrats | Ed Davey | 72 | 11.1% | 3,519,199 | 12.2% | |||

| Scottish National Party | John Swinney | 9 | 1.4% | 724,758 | 2.5% | |||

| Sinn Féin | Mary Lou McDonald | 7 | 1.1% | 210,891 | 0.7% | |||

| Independent | — | 6 | 0.9% | 564,243 | 2.0% | |||

| Reform UK | Nigel Farage | 5 | 0.8% | 4,117,221 | 14.3% | |||

| Democratic Unionist Party | Gavin Robinson | 5 | 0.8% | 172,058 | 0.6% | |||

| Green Party of England and Wales | Carla Denyer Adrian Ramsay | 4 | 0.6% | 1,841,888 | 6.4% | |||

| Plaid Cymru | Rhun ap Iorwerth | 4 | 0.6% | 194,811 | 0.7% | |||

| Social Democratic and Labour Party | Colum Eastwood | 2 | 0.3% | 86,861 | 0.3% | |||

| Alliance Party of Northern Ireland | Naomi Long | 1 | 0.2% | 117,191 | 0.4% | |||

| Ulster Unionist Party | Doug Beattie | 1 | 0.2% | 94,779 | 0.3% | |||

| Traditional Unionist Voice | Jim Allister | 1 | 0.2% | 48,685 | 0.2% | |||

| Speaker | Lindsay Hoyle | 1 | 0.2% | 25,238 | 0.1% | |||

Full results[edit]

| Affiliate | Leader | Candidates | MPs | Aggregate votes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Gained [x] | Lost [x] | Net | Of total (%) | Total | Of total (%) | Change (%) | ||||

| Labour | Keir Starmer | 631 | 411 | 218 | 7 | 63.2 | 9,704,655 | 33.69 | |||

| Conservative | Rishi Sunak | 635 | 121 | 1 | 252 | 18.6 | 6,827,311 | 23.7 | |||

| Reform UK | Nigel Farage | 609 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0.8 | 4,117,221 | 14.29 | |||

| Liberal Democrats | Ed Davey | 630 | 72 | 64 | 0 | 11.1 | 3,519,199 | 12.22 | |||

| Green Party of England and Wales | Carla Denyer & Adrian Ramsay | 574 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0.6 | 1,841,888 | 6.39 | |||

| Scottish National Party | John Swinney | 57 | 9 | 1 | 40 | 1.4 | 724,758 | 2.52 | |||

| Independents | — | 459 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0.9 | 564,243 | 1.96 | |||

| Sinn Féin | Mary Lou McDonald | 14 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 210,891 | 0.73 | |||

| Workers Party | George Galloway | 152 | 0 | 0 | 0[y] | 0.0 | 210,194 | 0.73 | |||

| Plaid Cymru | Rhun ap Iorwerth | 32 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0.6 | 194,811 | 0.68 | |||

| Democratic Unionist | Gavin Robinson | 16 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0.8 | 172,058 | 0.6 | |||

| Alliance | Naomi Long | 18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | 117,191 | 0.41 | |||

| Ulster Unionist | Doug Beattie | 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.2 | 94,779 | 0.33 | |||

| Scottish Greens | Patrick Harvie & Lorna Slater | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 92,685 | 0.32 | |||

| Social Democratic & Labour | Colum Eastwood | 18 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 86,861 | 0.3 | |||

| Traditional Unionist Voice | Jim Allister | 14 | 1 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.1 | 48,685 | 0.17 | — | |||

| Social Democratic Party | William Clouston | 122 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 33,811 | 0.12 | |||

| Speaker[z] | Lindsay Hoyle | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 25,238 | 0.09 | |||

| Yorkshire Party | Bob Buxton & Simon Biltcliffe | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 17,227 | 0.06 | |||

| Independent Network | 5 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 13,663 | 0.05 | — | ||||

| Trade Unionist & Socialist | Dave Nellist | 40 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 12,562 | 0.04 | — | |||

| Alba | Alex Salmond | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0[aa] | 0.0 | 11,784 | 0.04 | |||

| Rejoin EU | Brendan Donnelly | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9,245 | 0.03 | |||

| Green Party (NI) | Mal O'Hara | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8,692 | 0.03 | |||

| People Before Profit | Collective leadership[ab] | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8,438 | 0.03 | |||

| Aontú | Peadar Tóibín | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7,466 | 0.03 | |||

| Newham Independents Party | Mehmood Mirza | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 7,180 | 0.02 | New | |||

| Heritage Party | David Kurten | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6,597 | 0.02 | |||

| UK Independence Party | Nick Tenconi (interim) | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6,530 | 0.02 | |||

| Liberal Party | Steve Radford | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6,375 | 0.02 | |||

| Ashfield Independents | Jason Zadrozny | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6,276 | 0.02 | |||

| Monster Raving Loony | Howling Laud Hope | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5,814 | 0.02 | |||

| Christian Peoples Alliance | Sidney Cordle | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5,604 | 0.02 | |||

| Scottish Family | Richard Lucas | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5,425 | 0.02 | |||

| English Democrats | Robin Tilbrook | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5,182 | 0.02 | |||

| Party of Women | Kellie-Jay Keen | 16 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 5,077 | 0.02 | New | |||

| Lincolnshire Independents | Marianne Overton | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4,277 | 0.01 | |||

| One Leicester | Rita Patel | 2 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 4,008 | 0.01 | New | |||

| Socialist Labour Party | Jim McDaid | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,609 | 0.01 | |||

| Liverpool Community Independents | Alan Gibbons | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 3,293 | 0.01 | New | |||

| Swale Independents | Mike Baldock | 1 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 3,238 | 0.01 | — | |||

| Hampshire Independents | Alan Stone | 10 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 2,872 | 0.01 | New | |||

| Communist Party of Britain | Robert Griffiths | 14 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 2,622 | 0.01 | — | |||

| Democracy for Chorley | Ben Holden-Crowther | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 2,424 | 0.01 | New | |||

| Independent Oxford Alliance | Anne Gwinett | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 2,381 | 0.01 | New | |||

| Climate Party | Edmund Gemmell | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,967 | 0.01 | |||

| South Devon Alliance | Richard Daws | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 1,924 | 0.01 | New | |||

| British Democratic Party | Andrew Brons | 4 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 1,860 | 0.01 | — | |||

| True and Fair Party | Gina Miller | 4 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 1,695 | 0.01 | — | |||

| Alliance for Democracy and Freedom | 9 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 1,586 | 0.01 | New | ||||

| North East Party | Brian Moore | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,581 | 0.01 | |||

| English Constitution Party | Graham Moore | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,563 | 0.01 | |||

| Abolish the Welsh Assembly Party | Richard Suchorzewski | 3 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 1,521 | 0.01 | — | |||

| Animal Welfare Party | Vanessa Hudson | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,486 | 0.01 | |||

| Consensus | Ian Berkeley-Hurst | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 1,289 | 0 | New | |||

| Women's Equality Party | Mandu Reid | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,275 | 0 | |||

| Workers Revolutionary Party | Joshua Ogunleye | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,190 | 0 | |||

| Propel | Neil McEvoy | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 1,041 | 0 | New | |||

| Scottish Socialist Party | Colin Fox & Natalie Reid | 2 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 1,007 | 0 | — | |||

| Independent Alliance (Kent) | Francis Michael Taylor | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 926 | 0 | New | |||

| Freedom Alliance | 5 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 895 | 0 | New | ||||

| Christian Party | George Hargreaves | 2 | 0 | Coalition with CPA in 2019 | 0.0 | 806 | 0 | — | |||

| Confelicity | James Miller | 2 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 750 | 0 | New | |||

| Portsmouth Independents Party | Brian Moore | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 733 | 0 | New | |||

| Independence for Scotland Party | Colette Walker | 2 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 678 | 0 | New | |||

| Shared Ground | Thomas Hall | 2 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 664 | 0 | New | |||

| Cross-Community Labour Alternative | Owen McCracken | 1 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 624 | 0 | — | |||

| British Unionist Party | John Ferguson | 2 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 614 | 0 | New | |||

| Transform | Anwarul Khan | 2 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 595 | 0 | New | |||

| Putting Crewe First | Brian Silvester | 1 | 0 | New | 0.0 | 588 | 0 | New | |||

| Scottish Libertarian Party | Tam Laird | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 536 | 0 | |||

| Peace Party | John Morris | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 531 | 0 | |||

| Taking the Initiative Party | Nicola Zingwari | 1 | 0 | Did not stand in 2019 | 0.0 | 503 | 0 | — | |||

| Parties with fewer than 500 votes each | 51 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 11,163 | 0.04 | N/A | ||||

| Blank and invalid votes | TBD | — | — | ||||||||

| Total | 4,515 | 650 | 0 | 100.0 | 28,805,931 | 100.00 | 0.0 | ||||

| Registered voters, and turnout | 48,214,128 | 59.75 | −7.77 | ||||||||

By nation and region[edit]

| ||||||||||||||

| Nation/Region | Seats | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab. | Cons. | Lib. Dems | SNP | Reform | Greens | PC | SF | DUP | Others | |||||

| East of England | 61 | 27 | 23 | 7 | — | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | 0 | |||

| East Midlands | 47 | 29 | 15 | 0 | — | 2 | 0 | — | — | — | 1 | |||

| London | 75 | 59 | 9 | 6 | — | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | 1 | |||

| North East | 27 | 26 | 1 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | 0 | |||

| North West | 73 | 65 | 3 | 3 | — | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | 2 | |||

| South East | 91 | 36 | 30 | 24 | — | 0 | 1 | — | — | — | 0 | |||

| South West | 58 | 24 | 11 | 22 | — | 0 | 1 | — | — | — | 0 | |||

| West Midlands | 57 | 38 | 15 | 2 | — | 0 | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | |||

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 54 | 43 | 9 | 1 | — | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | 1 | |||

| Scotland | 57 | 37 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 0 | — | — | — | — | 0 | |||

| Wales | 32 | 27 | 0 | 1 | — | 0 | 0 | 4 | — | — | 0 | |||

| Northern Ireland | 18 | — | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | 7 | 5 | 6 | |||

| Total | 650 | 411 | 121 | 72 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 12 | |||

The result was a landslide win for Labour and a historic loss for the Conservatives. It was the latter's worst result since formalising as a party in the early 19th century, and the largest defeat for any incarnation since the 1761 British general election when they achieved 112 MPs though that made up a higher percentage of seats in Parliament due to its then smaller size of 577 MPs. The Conservatives won no seats in Wales or various English counties, including Cornwall and Oxfordshire (the latter historically known for having several safe Conservative seats), and they only won one seat in North East England.[385] Keir Starmer became the fourth prime minister in a two-year period.[386] Turnout, at 59.9%, was the second lowest since 1885 with only 2001 being lower at 59.4%.[387]

Four independent candidates (Ayoub Khan, Adnan Hussain, Iqbal Mohamed, Shockat Adam) outright defeated Labour candidates as well as one (Claudia Webbe) acting as a spoiler to defeat one in areas with large Muslim populations; the results were suggested to be a push-back against Labour''s stance on the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip in the Israel–Hamas war.[388][389][390][391][392][393] Additionally, Wes Streeting retained his seat by a margin of only 528 votes following a challenge by independent British-Palestinian candidate Leanne Mohamad,[394] while prominent Labour MP Jess Phillips retained her Birmingham Yardley constituency by a margin of 693 votes.[395] Despite this, Labour candidate Paul Waugh won the seat of Rochdale from George Galloway.[396] In Islington North, Jeremy Corbyn defeated the Labour candidate with a majority of 7,247.[397]

The Liberal Democrats made significant gains to reach their highest ever number of seats, mostly gaining Conservative seats in Southern England. This was also the best performance since its predecessor Liberal Party won 158 seats in 1923. Reform UK had MPs elected to the Commons for the first time. Their leader, Nigel Farage, was elected to Parliament on what was his eighth attempt.[398] The Green Party of England and Wales also won a record number of seats.[385] The party's two co-leaders, Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay, both entered Parliament for the first time.[399]

The Scottish National Party (SNP) lost around three quarters of its seats to Scottish Labour.[3] Labour returned to being the largest party in Scotland and remained so in Wales, although their vote share fell in Wales.[400]

Because the Democratic Unionist Party lost 3 seats, Sinn Féin won the most seats in Northern Ireland, making it the first time an Irish nationalist party was the largest party in Parliament from Northern Ireland. The Traditional Unionist Voice entered the Commons for the first time.[401] In North Down, independent Unionist candidate Alex Easton emerged victorious over the Alliance Party incumbent Stephen Farry,[402] resulting in the election of a total of six independent MPs across the UK.

Proportionality concerns[edit]

The combined vote share for Labour and the Conservatives reached a record low, with smaller parties doing well. The election was highly disproportionate, as Labour won 63% of seats (411) with only 34% of the vote, while Reform won under 0.8% of seats (5) with 14.3% of the vote under the UK's first-past-the-post voting system.[403] The Liberal Democrats recorded their best ever seat result (72), despite receiving only around half the votes they did in 2010,[404] and fewer votes overall than Reform, although the party's seat share was again lower than its share of the vote. As Starmer's government was elected with the lowest share of the vote of any government since the 1832 Reform Act, journalist Fraser Nelson described Labour's electoral success as a "Potemkin landslide".[405] An editorial from The Guardian described the result as a "crisis of electoral legitimacy" for the incoming Labour government.[404]

According to political scientist John Curtice, the 2024 election was the most disproportional in British history and Labour's parliamentary majority was "heavily exaggerated" by the voting system.[406] Advocacy group Make Votes Matter found that 58% of voters did not vote for their elected MP. Make Votes Matter spokesman Steve Gilmore, Electoral Reform Society chief Darren Hughes, Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, and the Green Party's co-leader Adrian Ramsay were among the figures that called for electoral reform in the wake of the election. The campaigners said it was the "most disproportionate election in history".[407][408] The Gallagher index gave the election a 24.0 score, making it the least proportionate election in modern UK history, according to the index.[409]

| Party | Votes | Seats | Votes/seat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | 9,731,363 | 412 | 23,620 |

| Conservative | 6,827,112 | 121 | 56,422 |

| Liberal Democrat | 3,519,163 | 72 | 48,877 |

| Scottish National Party | 724,758 | 9 | 80,529 |

| Sinn Féin | 210,891 | 7 | 30,127 |

| Others | 842,013 | 7 | 120,288 |

| Reform UK | 4,106,661 | 5 | 821,332 |

| Democratic Unionist Party | 172,058 | 5 | 34,412 |

| Green | 1,943,258 | 4 | 485,815 |

| Plaid Cymru | 194,811 | 4 | 48,703 |

| Social Democratic and Labour Party | 86,861 | 2 | 43,431 |

| Alliance | 117,191 | 1 | 117,191 |

| Ulster Unionist Party | 94,779 | 1 | 94,779 |

| Workers Party of Britain | 210,194 | 0 | — |

| Alba | 11,784 | 0 | — |

Aftermath[edit]

At around 05:00 on 5 July, Sunak conceded defeat to Starmer at the declaration at Sunak's seat of Richmond and Northallerton, before Labour had officially secured a majority.[410] In his resignation speech later that morning, Sunak apologised to Conservative voters and candidates for the party's defeat, and also offered support to Starmer and expressed hope he would be successful, saying:[411]

Whilst he has been my political opponent, Sir Keir Starmer will shortly become our Prime Minister. In this job, his successes will be all our successes, and I wish him and his family well. Whatever our disagreements in this campaign, he is a decent, public-spirited man, who I respect. He and his family deserve the very best of our understanding, as they make the huge transition to their new lives behind this door, and as he grapples with this most demanding of jobs in an increasingly unstable world.

Starmer succeeded Sunak as prime minister, ending 14 years of Conservative rule. In his first speech as prime minister, Starmer paid tribute to Sunak, saying "His achievement as the first British Asian Prime Minister of our country should not be underestimated by anyone", and also recognised "the dedication and hard work he brought to his leadership" but said that the people of Britain had voted for change:[412]

You have given us a clear mandate, and we will use it to deliver change. To restore service and respect to politics, end the era of noisy performance, tread more lightly on your lives, and unite our country. Four nations, standing together again, facing down, as we have so often in our past, the challenges of an insecure world. Committed to a calm and patient rebuilding. So with respect and humility, I invite you all to join this government of service in the mission of national renewal. Our work is urgent and we begin it today.

The Conservative Party's total of 121 seats was the largest ever defeat in the history of the present day post–Tamworth Manifesto Conservative Party, and the lowest total of MPs for any incarnation of the Tories/Conservatives since the 1761 British general election when they achieved 112 MPs, although that made up a higher percentage of seats in Parliament (20.1% as opposed to 18.6% in 2024) due to the smaller sized House of Commons in 1761 of 558 MPs.

See also[edit]

- 2020s in United Kingdom political history

- 2024 in politics and government

- 2024 United Kingdom general election in England

- 2024 United Kingdom general election in Northern Ireland

- 2024 United Kingdom general election in Scotland

- 2024 United Kingdom general election in Wales