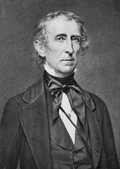

Abel P. Upshur

Abel P. Upshur | |

|---|---|

| |

| 15th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office July 24, 1843 – February 28, 1844 Ad interim: June 24, 1843 – July 24, 1843 | |

| President | John Tyler |

| Preceded by | Daniel Webster |

| Succeeded by | John C. Calhoun |

| 13th United States Secretary of the Navy | |

| In office October 11, 1841 – July 23, 1843 | |

| President | John Tyler |

| Preceded by | George Badger |

| Succeeded by | David Henshaw |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from the Northampton County, Virginia district | |

| In office November 29, 1824 – 1826 Serving with William Dunton and John Stratton | |

| Preceded by | Smith Nottingham |

| Succeeded by | William Dunton |

| In office November 30, 1812 – May 16, 1813 Serving with George T. Kendall | |

| Preceded by | William Dunton |

| Succeeded by | John C. Parramore |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Abel Parker Upshur June 17, 1790 Northampton County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | February 28, 1844 (aged 53) Potomac River, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Dennis (Deceased 1817) Elizabeth Brown |

| Education | Yale University College of New Jersey (renamed Princeton) |

Abel Parker Upshur (June 17, 1790 – February 28, 1844) was an American lawyer, planter, judge, and politician from the Eastern Shore of Virginia.[1] Active in Virginia state politics for decades, with a brother and a nephew who became distinguished U.S. Navy officers, Judge Upshur left the Virginia bench to become the Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of State during the administration of President John Tyler, a fellow Virginian. He negotiated the treaty that led to the 1845 Texas annexation to the United States and helped ensure that it was admitted as a slave state. Upshur died on February 28, 1844, when a gun on the warship USS Princeton exploded during a demonstration.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Upshur was born in Northampton County on Virginia's Eastern Shore, in 1790, one of 12 children borne to the former Anne Parker and her husband Littleton Upshur.[3] He was named after his paternal grandfather, who died on March 25, 1790. His maternal grandfather was George Parker. Littleton Upshur was reportedly a "staunch individualist and rabid Federalist",[3] owned the plantation Vaucluse,[4] was elected several times to both Houses of the Virginia General Assembly (beginning with his election to the House of Delegates in 1807),[5][3] and served as a captain in the U.S. Army during the War of 1812, which began in part after raids on Eastern Shore plantations.[3] His brother George P. Upshur (1799–1852)[6] became a distinguished naval officer; another brother was John Brown Upshur (1776–1822). His niece Mary Jane Stith Sturges (1828–1891) married New Yorker Josiah R. Sturges after the Civil War, helped organize the Harlem Free Hospital and published a historical novel, Confederate Notes, in 1867, either anonymously or under the pseudonym "Fanny Fielding".

After receiving a basic education through private tutors suitable for his class, Upshur attended Princeton University and Yale College;[4][7] he was expelled from the former for participating in a student rebellion.[3][4] He graduated from neither institution, instead returning to Richmond, Virginia, to study law with William Wirt.[3][8]

Marriage and family

[edit]Upshur first married Elizabeth Dennis in Accomack County, Virginia on February 26, 1817; she died in childbirth on November 28, 1817. He remarried, this time to his second cousin,[9] Elizabeth Ann Brown (née Upshur); they had one daughter, Susan Parker Brown Upshur (1826–1858).[10]

Virginia planter, lawyer and politician

[edit]Admitted to the Virginia bar in 1810; Upshur briefly set up practice in Baltimore, Maryland,[7] but returned to Virginia after his father's death.[4] He operated Vauclose plantation using enslaved labor, as had his father, and developed a law practice as well as became active in state politics.[7] In the reconstructed 1790 census, the senior Abel Upshur was tithed for 13 blacks, one black between 12 and 16 years old, 15 horses and 4 chariots.[11] In the 1820 federal census, Littleton Upshur owned 43 slaves.[12] In the 1830 federal census, Judge Abel Upshur owned 17 slaves and employed 3 free colored people, and Col. Littleton Upshur owned 20 slaves.[13] In the 1840 federal census, Abel Upshur owned 21 slaves.[14]

Upshur was first elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1812, while his father represented both Northampton and neighboring Accomac County in the Virginia Senate (both part-time positions).[15] As the War of 1812 ended, Upshur remained in the state capital, serving as Commonwealth's Attorney for Richmond (1816–1823). He ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Congress. Northampton County voters returned him as one of their legislative delegates in 1825, and re-elected him in 1826, but he did not fill the second term, since fellow delegates elected him as a judge of the Virginia General Court in 1826.[4][7]

Throughout his political career, Upshur was a slaveholder, as well as stalwart conservative and advocate for states' rights. Upshur again won election in 1829, this time as one of the four delegates representing Mathews, Middlesex, Accomac, Northampton and Gloucester Counties in the Virginia State Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830, where he served alongside Thomas R. Joynes, Thomas M. Bayley and William K. Perrin (replacing the deceased Calvin Read).[16] At the convention, Upshur represented eastern slaveholders and became the man who spoke the most against democratic reforms. He expressed similar views during the nullification movement in South Carolina in 1832; he defended the principle of nullification and the state in a series of letters entitled "An Exposition of the Virginia Resolutions of 1798". In 1839, Upshur also set forth his white supremacist views in an essay published by Richmond's Southern Literary Messenger.[17] (Although Upshur opposed universal white manhood suffrage at that constitutional convention, such would happen at the next constitutional convention, in 1850, after Upshur's death.)

Although a Federalist in his youth, Upshur became a states rights man in 1816, even a Jacksonian Democrat. However, after President Andrew Jackson (a slave owner himself) refused to countenance South Carolina's nullification, he changed parties again and became a Whig.[18] Upshur's view of the Constitution received its fullest expression in his 1840 treatise in response to Judge Joseph Story, A Brief Enquiry into the Nature and Character of our Federal Government: Being a Review of Judge Story's Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States.

The reorganized state legislature again elected Upshur judge of the Northampton Circuit Court, and he continued in that position until 1841, when he became Secretary of the Navy, as described below.[6]

Secretary of the Navy

[edit]After John Tyler became President of the United States in 1841, he appointed longtime friend Upshur as the 13th United States Secretary of the Navy in October of that year. His time with the Navy was marked by a strong emphasis on reform and reorganization, and efforts to expand and modernize the service. He served from October 11, 1841, to July 23, 1843. Among his achievements were the replacement of the old Board of Navy Commissioners with the bureau system, regularization of the officer corps, increased Navy appropriations, construction of new sailing and steam warships, and the establishment of the United States Naval Observatory and Hydrographic Office. Abel P. Upshur was also a staunch advocate for the expansion of the size of the U.S. Navy. Upshur sought the United States Navy to be at least half the size of the British Royal Navy.[19][20]

Upshur's zeal for a vastly expanded and empowered Federal navy struck some as being at odds with his fastidious advocacy of states’ rights and limited central government. The abolitionist and naval expansionist Congressman John Quincy Adams noted in his diary: “This new-born passion of the South for the increase of the navy is one of the most curious phenomena in our national history. From Jefferson’s dry-docks and gunboats, to admirals, three-deckers, and war-steamers equal to half the navy of Great Britain, is more than a stride—there is a flying-fish’s leap.”[21] But for Southern navalists like Upshur, there was no contradiction. Both stances were necessary for the defense of the South's especially vulnerable “social institutions” from abolitionism—domestic, in the case of states’ rights; British, in the case of geopolitics.[22]

Secretary of State

[edit]In July 1843, President Tyler appointed Upshur United States Secretary of State to succeed Daniel Webster, who had resigned. His chief accomplishment was advocating for the annexation of the Republic of Texas as a slave state. The Republic of Texas was initially hesitant to join the United States due to uncertainty of it being accepted, until Upshur transmitted a telegraph promising statehood upon request. Upshur and Texas ambassador Isaac Van Zandt worked closely on the treaty of annexation until Upshur's death. He was also deeply involved in the negotiations in the Oregon boundary dispute and was a strong advocate of bringing the Oregon Country into the union. He was eventually willing to settle on the 49th parallel compromise for the northern border between the United States and Canada, although negotiations were not finished until after his death and the end of Tyler's term as president.[23]

USS Princeton explosion and death

[edit]On February 28, 1844, Upshur joined President Tyler and about 400 other dignitaries examining the new steamship USS Princeton, which sailed down the Potomac River from Alexandria, Virginia. He and Gilmer, his successor as Secretary of the Navy, and four other passengers died when one of the ship's guns exploded near Fort Washington, Maryland, during a demonstration of its firing power, and many other officers and passengers were wounded.[24] Upshur was buried at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC. In 1874, later his remains were reinterred at Oak Hill Cemetery.[25]

Legacy

[edit]- The destroyer USS Abel P. Upshur was commissioned in 1920, and was later a Lend-Lease ship for Great Britain.

- In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS Abel Parker Upshur was named in his honor.

These places have been named for him:

- Upshur County, West Virginia

- Upshur Street in northwest Washington, DC;[26] Arlington, Virginia; Maryland; and northwest Portland, Oregon.

- Upshur County, Texas (interestingly, the county seat - Gilmer - is named for Thomas Walker Gilmer, another victim of the USS Princeton explosion)

- Mount Upshur, known as Boundary Peak 17, a summit on the Alaska-British Columbia border near Hyder, Alaska.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography vol. VI p. 213

- ^ "Abel Upshur" in Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography (a/k/a VBE) (1915) available online at ancestry.com

- ^ a b c d e f William H. Wroten Jr. (January 4, 1963). "Abel Parker Upshur". Salisbury Times. Delmarva Heritage Series. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "American President: Abel P. Upshur (1843–1844)". Miller Center. Archived from the original on October 6, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ Cynthia Miller Leonard, Virginia's General Assembly 1619–1978 (Richmond: Virginia State Library 1978) p. 249

- ^ a b Appleton's Cyclopedia Vol. VII p. 213

- ^ a b c d Naval Historical Center (May 29, 2000). "Upshur, Abel P., Secretary of the Navy, October 1841 – July 1843". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on October 12, 2000. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ VBE

- ^ Burton, Dr. William S. "Descendants of Littleton Ushur I". Genealogy & Historie Of The Eastern Shore (GHOTES) of Virginia. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Peabody Normal College (1896). "The Family of Sir George Yeardley". American Historical Magazine. 1. Nashville, Tennessee: University Press: 367–368. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ 1790 Reconstructed U.S. Census for Northampton County, Virginia available online at ancestry.com and based on Virginia Personal Property Tax List

- ^ 1820 U.S. Federal Census for Northampton County, Virginia p. 29

- ^ 1830 U.S. Federal Census for Northampton County, Virginia pp. 13–14 of 34

- ^ 1840 U.S. Federal Census for Northampton County, Virginia pp. 24–25 of 55

- ^ Leonard p. 271

- ^ Leonard p. 354

- ^ Brent Tartar, The Grandees of Government (University of Virginia Press 2013) pp. 156–159, citing in part "On Domestic Slavery" in Southern Literary Messenger (1839) p. 678

- ^ Virginia Biographical Encyclopedia available online

- ^ Hall, Claude H. “Abel P. Upshur and the Navy as an Instrument of Foreign Policy.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 69, no. 3, 1961, pp. 290–299 [293].

- ^ Karp, Matthew J. “Slavery and American Sea Power: The Navalist Impulse in the Antebellum South.” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 77, no. 2, 2011, p. 317. JSTOR website Retrieved 12 Jan. 2023.

- ^ John Quincy Adams, Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams, 12 vols. (New York: AMS Press, 1970 [1874–1877]), 11:95, 139–40

- ^ S. Doc. No. 1/6, 27th Cong., 2nd Sess.: Report of the Secretary of the Navy (1841), 379

- ^ "Edward P. Crapol, John Tyler and the Pursuit of National Destiny". Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Congressional Cemetery". December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown, D.C. (North Hill) – Lot 159" (PDF). oakhillcemeterydc.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Tom (December 21, 2015). "A Brief History Behind the Street Names of Washington, D.C." Ghosts of DC. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ "Upshur, Mount". BC Geographical Names.

Further reading

[edit]- Hall, Claude Hampton, Abel Parker Upshur: Conservative Virginian, 1790–1844. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1963.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch