John Bell (Tennessee politician)

John Bell | |

|---|---|

Bell in 1858 | |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

| In office November 22, 1847 – March 3, 1859 | |

| Preceded by | Spencer Jarnagin |

| Succeeded by | Alfred O. P. Nicholson |

| 16th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office March 5, 1841 – September 11, 1841 | |

| President | William Henry Harrison John Tyler |

| Preceded by | Joel Poinsett |

| Succeeded by | John Spencer |

| 12th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office June 2, 1834 – March 3, 1835 | |

| Preceded by | Andrew Stevenson |

| Succeeded by | James K. Polk |

| Chair of the House Judiciary Committee | |

| In office 1832–1834 | |

| Preceded by | Warren R. Davis |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Flournoy Foster |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 7th district | |

| In office March 4, 1827 – March 3, 1841 | |

| Preceded by | Sam Houston |

| Succeeded by | Robert L. Caruthers |

| Member of the Tennessee Senate | |

| In office 1817 | |

| Member of the Tennessee House of Representatives | |

| In office 1847 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 18, 1796 Mill Creek, Southwest Territory, U.S. |

| Died | September 10, 1869 (aged 73) Stewart County, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Olivet Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (1817–1825) Jacksonian (1825–1835) Whig (1835–1854) American (1854–1860) Constitutional Union (1860–1861) |

| Spouses | Sally Dickinson (m. 1818; died 1832)Jane Erwin Yeatman (m. 1835) |

| Children | 5 |

| Education | University of Nashville (BA) |

| Signature | |

John Bell (February 18, 1796 – September 10, 1869) was an American politician, attorney, and planter who was a candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1860.

One of Tennessee's most prominent antebellum politicians,[1] Bell served in the House of Representatives from 1827 to 1841, and in the Senate from 1847 to 1859. He was Speaker of the House for the 23rd Congress (1834–1835), and briefly served as Secretary of War during the administration of William Henry Harrison (1841). In 1860, he ran for president as the candidate of the Constitutional Union Party, a third party which took a neutral stance on the issue of slavery.[1] He won the electoral votes of three states by a slim margin.

Initially an ally of Andrew Jackson, Bell turned against Jackson in the mid-1830s and aligned himself with the National Republican Party and then the Whig Party, a shift that earned him the nickname "The Great Apostate".[2][3] He consistently battled Jackson's allies, namely James K. Polk, over issues such as the national bank and the election spoils system. Following the death of Hugh Lawson White in 1840, Bell became the acknowledged leader of Tennessee's Whigs.[1]

Although a slaveholder,[4] Bell was one of the few Southern politicians to oppose the expansion of slavery to the territories in the 1850s, and he campaigned vigorously against secession in the years leading up to the American Civil War.[1] During his 1860 presidential campaign, he argued that secession was unnecessary since the Constitution protected slavery, an argument that resonated with voters in border states, helping him capture the electoral votes of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia. After the Battle of Fort Sumter in April 1861, marking the beginning of the Civil War, Bell abandoned the Union cause and supported the Confederacy.[1]

Early life and career

[edit]John Bell was born in Mill Creek, a hamlet near Nashville in the Southwest Territory. He was one of nine children of the local farmer and blacksmith Samuel Bell and Margaret (Edmiston) Bell. His paternal grandfather, Robert Bell, had served in the American Revolution under Nathanael Greene, and his maternal grandfather, John Edmiston, had fought at Kings Mountain.[5]: 1–5 He graduated from Cumberland College (later renamed the University of Nashville) in 1814 and studied law. He was admitted to the bar in 1816 and established a prosperous practice in Franklin.[1]

Entering politics, he successfully ran for the Tennessee Senate in 1817. As a state senator, he supported judicial and state constitutional reform, and voted for moving the state capital to Murfreesboro (his wife, Sally Dickinson, was a granddaughter of the town's namesake, Hardy Murfree).[5]: 12 After serving a single term, Bell declined to run for reelection and instead moved to Nashville, where he established a law partnership with Henry Crabb.[5]: 11

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]In 1826, Bell ran for Tennessee's 7th District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, which had been vacated when the incumbent, Sam Houston, was elected governor. Bell and his opponent, Felix Grundy, engaged in a bitter campaign in which both claimed to support the initiatives of Andrew Jackson.[1] Although Jackson eventually endorsed Grundy, Bell was more popular with younger voters, and he won the election by just over a thousand votes.[5]: 21

Like many Southern congressmen, Bell opposed the Tariff of 1828. He also opposed federal funding for improvements to the Cumberland Road, arguing that the federal government lacked the constitutional authority to fund such a project. One of Bell's biggest initiatives was the Tennessee land bill, in which he and fellow Tennessee congressmen James K. Polk and Davy Crockett proposed the federal government give some of its lands in Tennessee to the state in order to establish public schools. Congressmen from eastern states rejected this, however, stating that Tennessee's mismanagement of its land resources was not the federal government's fault, and the bill was shelved.[5]: 25–32

During Bell's second term (1829–1831), he was chairman of the House Committee on Indian Affairs. As such, he wrote the Indian Removal Act, which was submitted by the committee in February 1830, and signed by President Jackson later that year.[5]: 39 This act led to the removal of the Cherokee and other tribes to Oklahoma, via the Trail of Tears, in the latter half of the decade. One of the bill's most vocal opponents was Massachusetts congressman Edward Everett, Bell's future running mate in the 1860 presidential election.[5]: 40

Following the shake-up of Jackson's cabinet in the wake of the Petticoat affair in 1831, Senator Hugh Lawson White recommended Bell for Secretary of War, but the appointment went to Lewis Cass instead. Bell nevertheless remained a staunch Jackson ally through his third term, opposing nullification and supporting the Force Bill.[5]: 59–65

The rift between Bell and Jackson began to show during Bell's fourth term (1833–1835). Jackson opposed the idea of a national bank and withdrew the government's deposits from the Bank of the United States in 1833. Bell was initially silent on the issue, while Polk defended the administration's actions on the House floor in April 1834. In June 1834, following the resignation of Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson, Polk sought the Speakership. Anti-Jacksonites threw their support behind Bell, however, and Bell was elected Speaker by a 114 to 78 vote.[5]: 71 Following his election, Bell stated he was not necessarily opposed to rechartering the bank, something that Jackson vigorously opposed, and Polk's allies assailed Bell in the press as a friend of the bank.[5]: 96

The final break with Jackson came in 1835 when Bell supported the presidential campaign of Hugh Lawson White, one of three members of the new Whig Party running against Jackson's chosen successor, Martin Van Buren. Jackson dismissed Bell, White, and long-time foe Davy Crockett as "hypocritical apostates."[5]: 111 When the House of Representatives convened in 1835, Polk mounted a strong campaign for the Speakership, and defeated Bell 132 to 84.[5]: 118 Jackson's friends were so elated at Bell's defeat that they held a gala at Vauxhall Gardens in Nashville, celebrating with champagne and the firing of cannons.[5]: 118

Bell spent much of his remaining House career sponsoring mostly unsuccessful legislation aimed at ending the spoils system. In 1837, he was again defeated by Polk for the Speakership, this time by a 116 to 103 vote.[5]: 140 In May of the following year, the House debated a bill to address Indian hostilities, with Bell arguing in favor of negotiation, and Jackson ally Hopkins L. Turney arguing for an authorization of military force. As Bell brushed off Turney as a "tool" of Jackson, Turney attacked Bell, and a fistfight erupted between the two.[5]: 150

In 1839, Jackson tried to convince former Tennessee governor William Carroll to run against Bell, but Carroll refused, saying no one could defeat Bell in his home district.[5]: 158 The Jacksonites finally convinced Robert Burton to run, but he was easily defeated by Bell in the general election. In March 1839, Bell's allies in the House engineered one last attack against Polk (who was retiring to run for governor) by removing the word "impartial" from his customary thanks for service.[5]: 157

Secretary of War

[edit]While Bell had won reelection in 1839, Tennessee's Whigs struggled at the state level, with incumbent Governor Newton Cannon losing to Polk, and the Democrats gaining control of the state legislature. Determined to revive the state's Whigs, Bell spent several weeks in 1840 canvassing the state for Whig politicians. Although he initially supported party leader Henry Clay for the Whig presidential nomination, he nevertheless campaigned for the eventual nominee, William Henry Harrison, helping him capture Tennessee's electoral votes on his way to winning the election. His efforts also helped Whig gubernatorial nominee James C. Jones defeat Polk.[5]: 168–174

When the newly elected President Harrison organized his cabinet in 1841, he offered the position of Secretary of War to Bell, following the advice of Daniel Webster. After Bell accepted, he was blasted as a hypocrite by Democrats, who pointed out that he had railed against the spoils system throughout the 1830s. After Harrison's death, his successor, John Tyler, agreed to keep all cabinet appointments, though many members of the cabinet were skeptical that Tyler, as a former Democrat who was effectively retired when he showed interest in the Whigs, would support Whig initiatives. In May 1841, Secretary Bell issued his report on the nation's defenses, suggesting they were outdated. He also recommended replacing civilian superintendents of national armories with military professionals, fearing that civilian superintendents lacked adequate knowledge of munitions storage.[5]: 189

As the cabinet members had feared, Tyler proved hostile to core Whig initiatives, vetoing a string of bills introduced by Clay and his allies in Congress and rejecting to hold cabinet votes on his decisions. Finally, on September 11, 1841, two days after Tyler vetoed the Fiscal Corporation bill, Bell and several other cabinet members followed Clay's order and resigned in protest.[5]: 187

Bell returned to Tennessee to focus on personal business affairs. He continued campaigning for Whig political candidates, however, helping Jones again defeat Polk in the 1843 gubernatorial election, and helping Whig nominee Clay narrowly capture the state's electoral votes over Polk in the 1844 presidential election, although Polk won the presidency.

Senate

[edit]In 1847, Bell returned to politics and was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. He was offered the House speakership, but he declined. Shortly afterward, the legislature, now controlled by Whigs, took up the task of filling one of the state's two U.S. Senate seats. The seat was held by a Whig, Spencer Jarnagin, who had angered the party by voting for the Walker tariff and thus had no chance of reelection. Bell, with the support of William "Parson" Brownlow's Jonesborough Whig and the Memphis Daily Eagle, was among those nominated to fill the seat. After several weeks and 48 rounds of voting, Bell finally received the necessary majority on November 22, 1847, beating, among others, John Netherland, Robertson Topp, William B. Reese, and Christoper H. Williams.[5]: 214

Shortly after his arrival in the Senate, Bell immediately began speaking out against the Mexican–American War, arguing it was a tyrannical endeavor of his old rival, James K. Polk, who was now president. He suggested that even if the war was defensive, the U.S. had no right to take over a portion of Mexico's territory. He was concerned, among other things, that the addition of new territory would bring the divisive issue of slavery back to the forefront of American politics, especially in light of the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in the new territories.[5]: 253 He nevertheless voted to ratify the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in March 1848.[5]: 225

As Bell had feared, sectional strife erupted in 1849 when California applied for statehood as a free state. Bell supported the state's admission, and clashed over the issue on the Senate floor with fellow Southern senators John C. Calhoun and John M. Berrien. Bell offered a compromise that would have allowed California to be admitted, and would have split New Mexico and a portion of western Texas into three new states, one free, and two slave states. In May, this compromise was shelved in favor of the package of bills proposed by Henry Clay, subsequently known as the Compromise of 1850. Bell mostly supported Clay's compromise, voting for the admission of California and the agreement on the territorial boundaries for New Mexico, but voted against the bill abolishing the slave trade in Washington, D.C.[5]: 261

During the latter half of his first term, Bell debated various bills regarding internal improvements, namely a bill subsidizing the construction of the Illinois Central Railroad (which he supported, though he thought proceeds from land sales should be evenly split among the states), and a bill subsidizing construction of the St. Mary's Falls Canal, which he opposed.[5]: 270 Bell was a steadfast supporter of Millard Fillmore, who had become president following the death of Zachary Taylor in 1850. Fillmore offered Bell the position of Secretary of the Navy in July 1852, but he turned it down.[5]: 273

During Bell's second term, which began following his reelection in 1853, the Senate was plagued by sectional strife. The fighting began in early 1854 over the bill that would eventually become the Kansas–Nebraska Act. To gain the support of Southern senators, the bill contained an amendment that repealed part of the Missouri Compromise to allow slavery north of the 36°30' parallel. Bell opposed this amendment, warning that a repeal of the Missouri Compromise would lead to endless sectional strife. He was assailed by Southern senators for this stance, and was blasted on the Senate floor by Robert Toombs of Georgia.[5]: 296 Bell was one of just two Southern senators (the other being Sam Houston) to vote against the final bill.[1][6]

The division between Northern and Southern Whigs over the Kansas-Nebraska Act doomed the party, with Northern Whigs shifting to the new Republican Party. In early September 1856, he was selected to be a delegate to the 1856 National Whig Convention.[7] The convention nominated former president Millard Fillmore, who had already been nominated by the American Party, or "Know Nothings". While he campaigned for Know Nothing candidates, Bell did not endorse many of the party's more controversial positions, such as its anti-Catholic stance.[5]: 304 Various newspapers, including Brownlow's Knoxville Whig, the New Orleans Delta, and the St. Louis Intelligencer, endorsed Bell as the American Party's presidential candidate, but the party's nomination went to Millard Fillmore.[5]: 305

In 1857, Democrats regained control of the Tennessee state legislature. They elected Andrew Johnson to fill the expiring term of Senator James C. Jones. Although Bell's term didn't expire for another two years, the legislature was so disgusted with him that they went ahead and chose his replacement (Alfred O. P. Nicholson) and demanded that he resign. He was continuously attacked by other Southern senators. In late 1857, he threatened to challenge Robert Toombs to a duel after Toombs called him an abolitionist, but Toombs retracted the statement.[5]: 319 In February 1858, Bell and Johnson were involved in a heated altercation on the Senate floor after Johnson questioned Bell's loyalty to the South.[5]: 324

In March 1858, Bell was one of just two Southern senators (the other being John J. Crittenden) to vote against the admission of Kansas under the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, ignoring orders from the Tennessee state legislature to vote for it.[5]: 328 In his last session in the Senate in 1859, Bell voted against an attempt to purchase Cuba from Spain, opposed the Homestead bill, and voted in favor of subsidies for the Pacific Railroad.[5]: 336

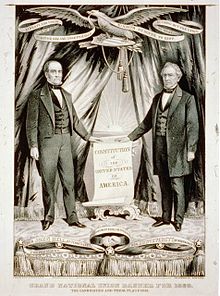

Presidential candidacy

[edit]

Annoyed by the continuous sectional strife in the Senate, Bell throughout the 1850s had pondered forming a third party to attract moderates from both the North and South.[5]: 265 By 1859, the Know Nothing movement had collapsed, but Tennessee's Whigs had organized themselves into the Opposition Party, which had won several of the state's congressional seats. Several of this party's supporters, among them Knoxville Whig editor William Brownlow, former vice presidential candidate Andrew Jackson Donelson, and California attorney Balie Peyton urged Bell to run for president on a third party ticket.[5]: 346

In May 1860, disgruntled ex-Whigs and disenchanted moderates from across the country convened in Baltimore, where they formed the Constitutional Union Party. The party's platform was very broad and made no mention of slavery. While there were several candidates for the party's presidential nomination, the two frontrunners were Bell and Sam Houston. On May 9, Bell led the initial round of balloting with 68 votes to Houston's 59, with more than a dozen other candidates splitting the remainder. Houston's military endeavors had brought him national renown, but he reminded the convention's Clay Whigs of their old foe Andrew Jackson. On May 10, Bell received 138 votes to Houston's 69, and was declared the candidate.[5]: 354 Edward Everett received the vice presidential nomination.[8]

While Bell had supporters throughout the Northern states and the border states, most of his Northern allies had thrown their support behind Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln or Democratic candidate Stephen A. Douglas. He had little support south of the border states, where Southern Democratic candidate John C. Breckinridge was the clear frontrunner. Southern Democratic newspapers slammed him as a friend of abolitionists and Republicans. The Nashville Union, referring to the Constitutional Union Party's noncommitted platform, derided Bell as "Nobody's man," who "stands on nobody's platform."[5]: 362 Bell also struggled with the youth vote, being more than a decade older than the next oldest candidate, Lincoln.[5]: 357

Seeing little chance of winning the election outright, Bell hoped that none of the three other candidates would get the required number of electoral votes and that the election would be sent to the House of Representatives, where he was convinced he would be chosen as a compromise since he was the only non-sectional candidate. Neither he nor Everett campaigned extensively.[5]: 368 However, Bell and his supporters knew they still needed to finish in the top three in the electoral college to be eligible for the contingent election as per the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment. The Constitutional Union campaign therefore directed most of its resources in the Upper South states which they believed they had the best chance of winning.

In the general election in November 1860, Bell received 592,906 popular votes (13% of the total; 39% of Southern popular votes). He finished third in the electoral college with 39 electoral votes (13%), nevertheless Lincoln secured a decisive victory by winning nearly all of the Northern electoral votes. Bell carried Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee with narrow pluralities over Breckinridge, but was narrowly defeated by Breckinridge in Maryland, North Carolina, Georgia, and Louisiana,[9] and by Douglas in Missouri, and lost badly in Delaware, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas. While Bell received less than 3% of the popular vote cast in Northern states, several of his electors were on fusion tickets with Douglas and Breckinridge electors, so this figure may not be representative of his actual support.[5]: 371

Civil War

[edit]

In the months following Lincoln's election, Bell remained steadfast in his support for the Union. During March 1861, he met Lincoln, who, according to Bell, said that he had no intention of using force against the South. After the Battle of Fort Sumter in April, however, Bell, despite continuing to believe in the illegality of secession, complained that he felt deceived by Lincoln. While he still supported preserving the Union if at all possible, he reasoned that if federal forces invaded Tennessee, they should be resisted. Accordingly, on April 23, he openly opposed Lincoln, called for the state to align itself with the Confederacy, and urged that it prepare a defense against a federal invasion.[5]: 398

Bell's defection to the Confederate cause stunned Unionist leaders. Louisville Journal editor George D. Prentice wrote that Bell's decision brought "unspeakable mortification, and disgust, and indignation" to his long-time supporters.[5]: 400 Horace Greeley lamented such an "ignominious close" to Bell's public career.[5]: 401 Knoxville Whig editor (and future Tennessee governor) William Brownlow derided Bell as the "officiating Priest" at the altar of the "false god of Disunion."[5]: 403

In June 1861, Bell traveled to Knoxville in hopes of converting the city's Unionist leaders to the secessionist cause and perhaps changing sentiments in the state's east, where most people remained pro-Union. On June 6, Bell delivered a speech before a crowd of secessionists at the Knox County Courthouse.[10] Following the speech, he walked across the street to the law office of long-time Whig attorney Oliver Perry Temple, where Temple and several other pro-Union leaders had gathered. Among them were Brownlow, Perez Dickinson, and William Rule. Temple later recalled:

Mr. Bell said, in a half-sad and half-complaining tone: "I see that none of my old friends were over to hear me speak." "No," said Mr. Brownlow, "we were not present, and did not intend being. We did not wish to witness the spectacle of your being surrounded by your enemies, who a few months ago were denouncing you as a traitor. We did not wish to hear these men shouting for you and see you in such a position." Mr. Brownlow then poured forth a torrent of abuse and denunciation of secession. Mr. Bell made no attempt to defend them, nor indeed to defend his own course.[10]

Brownlow had supported Bell for over two decades and, indeed, had named one of his sons after Bell. He recalled the incident in Temple's office when he came to write his 1862 book, Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession. In that volume, Brownlow stated he had criticized Bell that night with "great pain," and remembered that he and Bell "parted in tears."[11] Temple surmised that Bell's decision to support the Confederacy was driven by panic, for "there was not a drop of disloyal blood in his veins."[10]

After Tennessee seceded on June 8, Bell retired from public life, though his sons and sons-in-law actively supported the Confederate cause. When the Union Army occupied Tennessee in 1862, Bell fled to Huntsville, Alabama, and later to Georgia. After the war, he moved to Stewart County, Tennessee, where he managed his family-owned ironworks.[1] He died at his home near Dover, Tennessee in 1869, and he is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Nashville.

Family

[edit]Bell married his first wife, Sally Dickinson, in 1818. They had five children (Mary, John, David, Fanny, and Sally) before she died in 1832. Sally Dickinson was the sister of Congressman David W. Dickinson, the granddaughter of Hardy Murfree, and the aunt of author Mary Noailles Murfree.[5]: 12 In 1835, Bell married Jane Erwin Yeatman, a prominent socialite and widow of wealthy businessman Thomas Yeatman.

Confederate Congressman Edwin Augustus Keeble (1807–1868) was a son-in-law of Bell's, being married to his daughter, Sally.[5]: 12 Bell's great-grandson, also named Edwin A. Keeble, was a prominent Nashville-area architect, his best known design being the city's first skyscraper, the Life & Casualty Tower.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jonathan Atkins, "John Bell," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved: October 10, 2012.

- ^ Correspondence of James K. Polk, by James Knox Polk, Vol. 6 (1842–1843), p. 17

- ^ The Political Lincoln: An Encyclopedia, by Paul Finkelman and Martin J. Hershock, 2008, p. 52 [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, January 27, 2022, retrieved January 30, 2022

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at Joseph Parks, John Bell of Tennessee (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1950).

- ^ Anthony Gene Carey, Parties, Slavery, and the Union in Antebellum Georgia (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1997), p. 185.

- ^ "Old Lines Whig of Maury". Nashville Daily Patriot. Nashville, Tennessee. September 3, 1856. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Breckinridge had the support of the influential U.S. Senator John Slidell. Another Louisiana figure, Pierre Soulé, backed Douglas. John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 5

- ^ a b c Oliver Perry Temple, East Tennessee and the Civil War (Johnson City, Tenn.: Overmountain Press, 1995), pp. 234–236.

- ^ William G. Brownlow, Sketches of the Rise, Progress and Decline of Secession (Philadelphia: G.W. Childs, 1862), pp. 208–209.

Further reading

[edit]- Atkins, Jonathan M. (1997). Parties, Politics, and the Sectional Conflict in Tennessee, 1832–1861. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9780870499500.

- Caldwell, Joshua W. “John Bell of Tennessee: A Chapter of Political History.” The American Historical Review 4, no. 4 (1899): 652–64. online.

- Goodpasture, Albert V. “John Bell's Political Revolt, and His Vauxhall Garden Speech.” Tennessee Historical Magazine 2, no. 4 (1916): 254–63. online.

- Halladay, Bob (2004). "Ideas Have Consequences: Whig Party Politics in Williamson County, Tennessee, and the Road to Disunion". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 63 (3): 155–177. JSTOR 42631930.

- Holt, Michael Fitzgibbon (2017). The Election of 1860: A Campaign Fraught with Consequences. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780700624874.

- Murphy, James Edward (1971). "Jackson and the Tennessee Opposition". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 30 (1): 50–69. JSTOR 42623203.

- Parks, Joseph H. (1943). "John Bell and the Compromise of 1850". The Journal of Southern History. 9 (3): 328–356. doi:10.2307/2191320. JSTOR 2191320.

- Parks, Joseph Howard (1950). John Bell of Tennessee. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780598252647.

- Parks, Norman L. (1942). "The Career of John Bell as Congressman from Tennessee, 1827–1841". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 1 (3): 229–249. JSTOR 42620752.

- Pray, Carl Esek (1913). John Bell of Tennessee: His Career in the House of Representatives. University of Madison – Wisconsin.

john bell tennessee.

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "John Bell (id: B000340)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- "John Bell". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- The public record and past history of John Bell & Edward Everett

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch