Timeline of African-American firsts

This article contains one or more duplicated citations. The reason given is: DuplicateReferences detected: (September 2024)

|

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

African Americans are an ethnic group in the United States. The first achievements by African Americans in diverse fields have historically marked footholds, often leading to more widespread cultural change. The shorthand phrase for this is "breaking the color barrier".[1][2]

One prominent example is Jackie Robinson, who became the first African American of the modern era to become a Major League Baseball player in 1947, ending 60 years of racial segregation within the Negro leagues.[3]

| Contents |

|---|

| 17th century: 1670s |

17th century

[edit]1600s

[edit]1604

[edit]- First Black person to arrive in what is now Maine: explorer and interpreter Mathieu Da Costa[4]

1650

[edit]- First African American to own land in the United States July 24,1651: Anthony Johnson (colonist)

1670s

[edit]1670

[edit]- First African American to own land in Boston: Zipporah Potter Atkins[5]

18th century

[edit]1730s–1770s

[edit]1738

[edit]- First free African-American community: Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose (later named Fort Mose) in Spanish Florida[6]

1746

[edit]- First known African American (and slave) to compose a work of literature: Lucy Terry with her poem "Bars Fight", composed in 1746[7] and first published in 1855 in Josiah Holland's History of Western Massachusetts.[8][7]

1760

[edit]- First known African-American published author: Jupiter Hammon (poem "An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries", published as a broadside)[9]

1767

[edit]- First African-American clockmaker, Peter Hill, was born.[10]

1768

[edit]- First known African American to be elected to public office: Wentworth Cheswell, town constable and Justice of the Peace in Newmarket, New Hampshire.[11]

1773

[edit]- First known African-American woman to publish a book: Phillis Wheatley (Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral)[12]

- First separate African-American church: Silver Bluff Baptist Church, Aiken County, South Carolina[13][14][Note 1]

1775

[edit]- First African American to join the Freemasons: Prince Hall[15]

1778

[edit]- First African-American U.S. military regiment: the 1st Rhode Island Regiment[16]

1780s–1790s

[edit]

1783

[edit]- First African American to formally practice medicine: James Derham, who did not hold an M.D. degree.[17] (See also: 1847)

1785

[edit]- First African American ordained as a Christian minister in the United States: Rev. Lemuel Haynes. He was ordained in the Congregational Church, which became the United Church of Christ[18]

1792

[edit]- First major African-American Back-to-Africa movement: 3,000 Black Loyalist slaves, who had escaped to British lines during the American Revolutionary War for the promise of freedom, were relocated to Nova Scotia and given land. Later, 1,200 chose to migrate to West Africa and settle in the new British colony of Settler Town, which is present-day Sierra Leone. [citation needed]

1793

[edit]- First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church founded: Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, Philadelphia, was founded by Richard Allen[citation needed]

1794

[edit]- First African Episcopal Church established: Absalom Jones founded African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[citation needed]

1799

[edit]- First African American to attend college(Washington and Lee University): John Chavis, Later went on to be a preacher and educator for both black and white students.

19th century

[edit]1800s

[edit]

1804

[edit]- First African American ordained as an Episcopal priest: Absalom Jones in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[19]

1807

[edit]- First African-American Presbyterian Church in America: First African Presbyterian Church founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by John Gloucester a former slave.[20]

1810s

[edit]1816

[edit]- Richard Allen founded the first fully independent African-American denomination: African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and mid-Atlantic states[citation needed]

1817

[edit]- The First African Baptist Church was the first African-American church west of the Mississippi River.[21] It had its beginnings in 1817 when John Mason Peck and the former enslaved John Berry Meachum began holding church services for African Americans in St. Louis.[22] Meachum founded the First African Baptist Church in 1827. Although there were ordinances preventing blacks from assembling, the congregation grew from 14 people at its founding to 220 people by 1829. Two hundred of the parishioners were slaves, who could only travel to the church and attend services with the permission of their owners.[21]

1820s

[edit]1821

[edit]- First African American to hold a patent: Thomas L. Jennings, for a dry-cleaning process[23]

1822

[edit]- First African-American captain to sail a whaleship with an all-black crew: Absalom Boston[24] There were six black owners of seven whaling trips before Absalom Boston's in 1822.[25]

1823

[edit]- First African American to receive a degree from an American college: Alexander Twilight, Middlebury College[26] (See also: 1836)

1826

[edit]- First African American to graduate from Bowdoin College: Future governor of the Republic of Maryland, John Brown Russwurm[27]

1827

[edit]- First African-American-owned-and-operated newspaper: Freedom's Journal, founded in New York City by Rev. Peter Williams Jr.,[28] Samuel Cornish, John Brown Russwurm and other free blacks[27]

1830s

[edit]1832

[edit]- First governor of African descent in what is now the United States: Pío Pico, an Afro-Mexican, was the last governor of Alta California before it was ceded to the U.S. Like all Californios, Pico automatically became a U.S. citizen in 1848.[citation needed]

1836

[edit]- First African-American elected to serve in a state legislature: Alexander Twilight, Vermont[26] (See also: 1823)

- First African American to found a town and establish a planned community: Free Frank McWorter (New Philadelphia, Illinois)[29][30]

- First African-American governor of the Republic of Maryland or any other colony in Africa: John Brown Russwurm[31]

1837

[edit]- First formally trained African-American medical doctor: Dr James McCune Smith of New York City, who was educated at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, and returned to practice in New York.[32] (See also: 1783, 1847)

1840s

[edit]1844

[edit]- First African-American approved to practice law: Macon Bolling Allen from the bar association of Portland, Maine[33]

1845

[edit]- First African-American to practice law: Macon Bolling Allen from the Boston bar[34]

1847

[edit]- First African American to graduate from a U.S. medical school: Dr. David J. Peck[35] (Rush Medical College) (See also: 1783, 1837)

- First African-American president of any nation: Joseph Jenkins Roberts, Liberia[36]

1849

[edit]- First African-American college professor at a predominantly white institution: Charles L. Reason, New York Central College[37]

1850s

[edit]

1850

[edit]- First African-American woman to graduate from a college Lucy Stanton

1851

[edit]- First African-American member of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits): Patrick Francis Healy[38] (See also: 1866, 1874)

1853

[edit]- First novel published by an African-American: Clotel; or, The President's Daughter, by William Wells Brown, then living in London.[Note 2][39][40]

- First African-American to build and serve as captain of his own ship: Joseph P. Taylor of Portland, Maine[41]

1854

[edit]- First African-American Catholic priest: James Augustine Healy[42] (see 1875 and 1886)

- First institute of higher learning created to educate African-Americans: Ashmun Institute in Pennsylvania, renamed Lincoln University in 1866. (See also firsts in 1863)

1858

[edit]- First published play by an African-American: The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom by William Wells Brown[43]

- First African-American woman college instructor: Sarah Jane Woodson Early, Wilberforce College[44]

- First African-American woman to graduate from a medical course of study at an American university: Sarah Mapps Douglass

- First African-American Missionary Bishop of Liberia: Francis Burns of Windham, N.Y. of the Methodist Episcopal Church.[45]

1860s

[edit]1861

[edit]- First North American military unit with African-American officers: 1st Louisiana Native Guard of the Confederate Army

- First African-American US federal government civil servant: William Cooper Nell[46]

1862

[edit]- First African-American woman to earn a B.A.: Mary Jane Patterson, Oberlin College[47]

- First recognized U.S. Army African-American combat unit: 1st South Carolina Volunteers

1863

[edit]- First college owned and operated by African-Americans: Wilberforce University in Ohio[48][Note 3] (See also: 1854)

- First African-American president of a college: Bishop Daniel Payne (Wilberforce University)[49]

1864

[edit]- First African-American woman in the United States to earn an M.D.: Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler[50]

1865

[edit]- First African-American field officer in the U.S. Army: Martin Delany[51]

- First African-American attorney admitted to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court: John Stewart Rock[52]

- First African American to be commissioned as captain in the Regular U.S. Army: Orindatus Simon Bolivar Wall, known as OSB Wall[53]

1866

[edit]- First African American to earn a Ph.D.: Father Patrick Francis Healy from University of Leuven, Belgium[38] (See also 1851, 1874)

- First African-American woman enlistee in the U.S. Army: Cathay Williams[54]

- First African-American woman to serve as a professor: Sarah Jane Woodson Early; Xenia, Ohio's Wilberforce University hired her to teach Latin and English

1868

[edit]- First elected African-American Lieutenant Governor: Oscar Dunn (Louisiana).[55]

- First African-American mayor: Pierre Caliste Landry, Donaldsonville, Louisiana[56]

- First African-American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives: John Willis Menard.[57] His opponent contested his election, and opposition to his election prevented him from being seated in Congress. (See also: 1870)

1869

[edit]- First African-American U.S. diplomat: Ebenezer Don Carlos Bassett, minister to Haiti[58]

- First African-American woman school principal: Fanny Jackson Coppin (Institute for Colored Youth)[59]

- First African American to receive a dental degree and become a dentist: Robert Tanner Freeman[60]

1870s

[edit]1870

[edit]- First African American to vote in an election under the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, granting voting rights regardless of race: Thomas Mundy Peterson[61]

- First African American to graduate from Harvard College: Richard Theodore Greener.[62]

- First African-American elected to the U.S. Senate, and first to serve in the U.S. Congress: Hiram Rhodes Revels (R–MS).[63][Note 4]

- First African American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives: Joseph Rainey (R-SC).[64][Note 5]

- First African-American acting governor: Oscar James Dunn of Louisiana from May until August 9, 1871, when sitting Governor Henry C. Warmoth was incapacitated and chose to recuperate in Mississippi. (See also: Douglas Wilder, 1990)

1871

[edit]- First African-American page in the United States House of Representatives: Alfred Q. Powell, who was appointed in 1871 by Charles H. Porter (R-VA), with recommendations from William Henry Harrison Stowell (R-VA) and James H. Platt Jr. (R-VA).[65][66][67]

1872

[edit]- First African-American midshipman admitted to the United States Naval Academy: John H. Conyers (nominated by Robert B. Elliott of South Carolina).[68]

- First African-American governor (non-elected): P. B. S. Pinchback of Louisiana (See also: Douglas Wilder, 1990)[69]

- First African-American nominee for Vice President of the United States: Frederick Douglass by the Equal Rights Party.[70][Note 6]

1873

[edit]- First African-American speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives, and of any state legislature: John R. Lynch

1874

[edit]- First African-American president of a major college/university: Father Patrick Francis Healy, S.J. of Georgetown College.[38] (See also: 1851, 1863, 1866)

- First African American to preside over the House of Representatives as Speaker pro tempore: Joseph Rainey[71]

1875

[edit]- First African-American Roman Catholic bishop: Bishop James Augustine Healy, of Portland, Maine.[42] (See also: 1854)

1876

[edit]- First African American to earn a doctorate degree from an American university: Edward Alexander Bouchet (Yale College Ph.D., physics; also first African American to graduate from Yale, 1874).[72] (See also: 1866)

1877

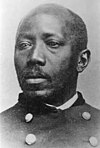

[edit]- First African-American graduate of West Point and first African-American commissioned officer in the U.S. military: Henry Ossian Flipper.[73]

- First African-American elected to Phi Beta Kappa: George Washington Henderson.[74]

1878

[edit]- First African-American police officer in Boston, Massachusetts: Sergeant Horatio J. Homer.[75]

- First African-American baseball player in organized professional baseball: John W. "Bud" Fowler.[76]

1879

[edit]- First African American to serve as a sheriff or chief of police in Vermont: Stephen Bates, Vergennes, Vermont.[77]

- First African American to graduate from a formal nursing school: Mary Eliza Mahoney, Boston, Massachusetts.[78]

- First African American to play major league baseball: Possibly William Edward White; he played as a substitute in one professional baseball game for the Providence Grays of the National League, on June 21, 1879.[79] Work by the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) suggests that he may have been the first African American to play major league baseball, predating the longer careers of Moses Fleetwood Walker and his brother Weldy Walker by five years; and Jackie Robinson by 68 years.[80][81][82][83][84]

1880s

[edit]1880

[edit]- First African American to command a U.S. ship: Captain Michael Healy.[85]

- First African-American world champion in pedestrianism, a 19th-century forerunner to racewalking and ultramarathons: Frank Hart.[86]

1881

[edit]- First African-American whose signature appeared on U.S. paper currency: Blanche K. Bruce, Register of the Treasury.[87]

1882

[edit]- First fully state-supported four-year institution of higher learning for African-Americans: Virginia State University

1883

[edit]- First known African-American woman to graduate from one of the Seven Sisters colleges: Hortense Parker (Mount Holyoke College)[88][Note 7]

- First African-American woman to earn a PhD. Nettie Craig-Asberry June 12, 1883, earns her doctoral degree in music from the University of Kansas one month shy of her 18th birthday.

1884

[edit]- First African American to play professional baseball at the major-league level: Possibly Moses Fleetwood Walker, but see also William Edward White in 1879.[89] (See also: Jackie Robinson, 1947)

- First African-American woman to hold a patent: Judy W. Reed, for an improved dough kneader, Washington, D.C.[90][Note 8]

- First African American to enlist in the U.S. Signal Corps: William Hallett Greene[91][92]

- First African American to lead a political party's National Convention: John R. Lynch, Republican National Convention.[93]

- First African American to deliver a keynote address at a political party's National Convention: John R. Lynch, Republican National Convention.[93]

1886

[edit]- First Roman Catholic priest publicly known at the time to be African-American: Augustine Tolton, Quincy and Chicago, Illinois[94] (See also: 1854)

1890s

[edit]1890

[edit]- First African-American woman to earn a dental degree in the United States: Ida Rollins, University of Michigan.[95][96]

- First African American to record a best-selling phonograph record: George Washington Johnson, "The Laughing Song" and "The Whistling Coon."[97]

- First woman and African American to earn a military pension for their own military service: Ann Bradford Stokes.[98]

1891

[edit]- First African-American police officer in present-day New York City: Wiley Overton, hired by the Brooklyn Police Department prior to 1898 incorporation of the five boroughs into the City of New York.[99] (See also: Samuel J. Battle, 1911)

1892

[edit]- First African American to sing at Carnegie Hall: Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones[100]

- First African-American named to a College Football All-America Team: William H. Lewis, Harvard University[101]

1895

[edit]- First African-American woman to work for the United States Postal Service: Mary Fields[102]

- First African American to earn a doctorate degree (Ph.D.) from Harvard University: W.E.B. Du Bois[103]

1896

[edit]- First African American female dentist to graduate from Howard University's dental school: Marie Imogene Williams.[104]

1898

[edit]- First African-American appointed to serve as U.S. Army Paymaster: Richard R. Wright

1899

[edit]- First African American to achieve world championship in any sport: Major Taylor, for 1-mile track cycling[105]

20th century

[edit]1900s

[edit]1901

[edit]- First African-American invited to dine at the White House: Booker T. Washington[106]

1902

[edit]- First African-American professional basketball player: Harry Lew (New England Professional Basketball League)[107] (See also: 1950)

- First African-American professional American football player: Charles Follis

- First African-American boxing champion: Joe Gans, a lightweight (See also: 1908)

1903

[edit]- First Broadway musical written by African-Americans, and the first to star African-Americans: In Dahomey

- First African-American woman to found and become president of a bank: Maggie L. Walker, St. Luke Penny Savings Bank (since 1930 the Consolidated Bank & Trust Company), Richmond, Virginia[108]

1904

[edit]- First Greek-letter fraternal organization founded by African-Americans: Sigma Pi Phi

- First African American to participate in the Olympic Games, and first to win a medal: George Poage (two bronze medals)[109]

1906

[edit]- First intercollegiate Greek-letter organization founded by African-Americans: Alpha Phi Alpha (ΑΦΑ), at Cornell University

- First academically trained African-American forester: Ralph E. Brock at the Pennsylvania State Forest Academy[110]

1907

[edit]- First African-American Greek Orthodox priest and missionary in America: Very Rev. Fr. Robert Josias Morgan[111]

1908

[edit]- First African-American heavyweight boxing champion: Jack Johnson[112] (See also: 1902)

- First African-American Olympic gold medal winner: John Taylor (track and field medley relay team).[113] (See also: DeHart Hubbard, 1924)

- First intercollegiate Greek-letter sorority established by African-Americans: Alpha Kappa Alpha (ΑΚΑ) at Howard University

1910s

[edit]1910

[edit]- First African-American female millionaire: Madam C. J. Walker[114]

- First African-American woman to be recorded commercially: Daisy Tapley[115]

1911

[edit]- First intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity founded by African-Americans at a historically black college: Omega Psi Phi (ΩΨΦ), at Howard University

- First African-American police officer in New York City: Samuel J. Battle, following the 1898 incorporation of the five boroughs into the City of New York, and the hiring of three African-American officers in the Brooklyn Police Department. Battle was also the NYPD's first African-American sergeant (1926), lieutenant (1935), and parole commissioner (1941).[99] (See also: Wiley Overton, 1891)

- First African-American attorney admitted to the American Bar Association: Butler R. Wilson (June 1911), William Henry Lewis (August 1911), and William R. Morris (October 1911)[116][117]

- First African-American elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly: Harry W. Bass (1911).[118]

1914

[edit]- First African-American military pilot: Eugene Jacques Bullard

- First African American to attend the University of Connecticut, earning his bachelor's degree with honors in 1918: Alan Thacker Busby.[119]

1915

[edit]- First African-American alderman of Chicago: Oscar Stanton De Priest[120]

1916

[edit]- First African American to play in a Rose Bowl game: Fritz Pollard, Brown University[121]

- First African American to become a colonel in the U.S. Army: Charles Young[122][123]

- First African-American woman to become a licensed pharmacist: Ella P. Stewart

1917

[edit]- First African-American woman to win a major sports title: Lucy Diggs Slowe, American Tennis Association[124]

1919

[edit]- First African-American special agent for the FBI: James Wormley Jones[125][126]

- First African-American women appointed as police officers: Cora I. Parchment at the New York Police Department (NYPD)[127] and Georgia Ann Robinson, by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD)[128]

- First African American to direct a feature film: Oscar Micheaux (The Homesteader)

1920s

[edit]1920

[edit]- First African-American NFL football players: Fritz Pollard (Akron Pros) and Bobby Marshall (Rock Island Independents)[129]

- First African-American bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church: Robert Elijah Jones and Matthew Wesley Clair.[130]

1921

[edit]

Bessie Coleman - First African-American NFL football coach: Fritz Pollard, co-head coach, Akron Pros, while continuing to play running back[129]

- First African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in the U.S.: Georgiana Rose Simpson, from the University of Chicago in 1921

- First African-American to found a record label: Harry Pace (Black Swan Records)

- First African-American to be licensed as a certified public accountant (CPA): John Wesley Cromwell Jr.[132]

1923

[edit]- First African-American woman to earn a degree in library science: Virginia Proctor Powell Florence.[133][134] She earned the degree (Bachelor of Library Science) from what is now part of the University of Pittsburgh.[135][136][137]

1924

[edit]- First African American to win individual Olympic gold medal: DeHart Hubbard (long jump, 1924 Summer Olympics).[138] (See also: John Taylor, 1908)

1925

[edit]- First African-American Foreign Service Officer: Clifton R. Wharton Sr.[139]

1927

[edit]- First African American to become an officer in the New York Fire Department in New York City: Wesley Augustus Williams.[140]

- First African-American woman to star in a foreign motion picture: Josephine Baker in La Sirène des tropiques.[141]

1928

[edit]- First post-Reconstruction African-American elected to U.S. House of Representatives: Oscar Stanton De Priest (Republican; Illinois)[142]

- First African-American woman to serve in a state legislature: Minnie Buckingham Harper, West Virginia[143]

1929

[edit]- First African-American sportscaster: Sherman "Jocko" Maxwell (WNJR, Newark, New Jersey)[144]

1930s

[edit]1930

[edit]- First African American to win a state high school basketball championship: David "Big Dave" DeJernett, star center on an integrated Washington, Indiana team.

1931

[edit]- First African-American composer to have their symphony performed by a leading orchestra: William Grant Still, Symphony No. 1, by Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra[145]

Jane Matilda Bolin

1932

[edit]- First African-American on a presidential ticket in the 20th century: James W. Ford (Communist Party USA, as vice-presidential candidate running with William Z. Foster)[146]

- First African-American Ph.D. in anthropology: William Montague Cobb[147][148]

1933

[edit]- First African-American woman to earn a doctorate in psychology: Inez Prosser

1934

[edit]- First African-American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat: Arthur W. Mitchell (Illinois)[149]

- First trade union set up for African-American domestic workers by Dora Lee Jones[relevant?]

1936

[edit]- First African American to conduct a major U.S. orchestra: William Grant Still (Los Angeles Philharmonic)[150]

- First African-American women selected for the Olympic Games: Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes.[151] Stokes did not compete; Picket competed in the 80-meter hurdles[152]: 86

1937

[edit]- First African-American federal magistrate: William H. Hastie (later the first African-American governor of the United States Virgin Islands)[153]

1938

[edit]- First African-American woman federal agency head: Mary McLeod Bethune (National Youth Administration)[154]

- First African-American woman elected to a state legislature: Crystal Bird Fauset (Pennsylvania General Assembly)

1939

[edit]- First African American to star in their own television program: Ethel Waters, The Ethel Waters Show, on NBC[155]

1940s

[edit]1940

[edit]

- First African American woman to win an Oscar: Hattie McDaniel (Best Supporting Actress, Gone with the Wind, 1939)[156]

- First African American to be portrayed on a U.S. postage stamp: Booker T. Washington[157]

- First African-American flag officer: BG Benjamin O. Davis Sr., U.S. Army[158][Note 9]

- First African American to earn a doctorate in library science: Eliza Atkins Gleason, from the University of Chicago[159]

1941

[edit]- First African American to give a White House Command Performance: Josh White[160]

1942

[edit]

- First African American to be awarded the Navy Cross: Doris Miller

- First African-American member of the U.S. Marine Corps: Alfred Masters[161]

- First African-American inadvertently commissioned in the U.S. Navy as a Limited duty Flight instructor: Oscar Holmes[162]

- First African American to captain a U.S. Merchant Marine ship, the SS Booker T. Washington: Hugh Mulzac[163]

1943

[edit]- Martin A. Martin, first African American to become a member of the Trial Bureau of the United States Department of Justice, was sworn in on May 31, 1943.[164]

- First African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics: Euphemia Haynes, from Catholic University of America[165]

1944

[edit]- First African-American commissioned Line officers in the U.S. Navy: The "Golden Thirteen"[166]

- First African-American commissioned as a U.S. Navy officer from the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps: Samuel Gravely[167][Note 10]

- First female African-American commissioned Navy officers: Harriet Ida Pickens and Frances Wills[168]

- First African American to receive a contract with a major U.S. opera company: Camilla Williams[169]

- First known African-American comic book artist: Matt Baker in Jumbo Comics #69 for Fiction House[170]

- First African-American reporter to attend a U.S. presidential news conference: Harry McAlpin[171]

1945

[edit]- First African-American member of the New York City Opera: Todd Duncan[relevant?]

- First African-American U.S. Marine Corps officer: Frederick C. Branch[172]

Olivia Hooker - First African-American woman to enter the Coast Guard: Olivia Hooker[174]

1946

[edit]- First African American to sign a contract with an NFL team in the modern (post-World War II) era: Kenny Washington

1947

[edit]

Jackie Robinson - First African-American Major League Baseball player in the American League: Larry Doby (Cleveland Indians).

- First African-American consensus college All-American basketball player: Don Barksdale[176]

- First comic book produced entirely by African-Americans: All-Negro Comics[177]

- First African-American full-time faculty member at a predominantly white law school: William Robert Ming (University of Chicago Law School)[37]

- First African-American female member of the U.S. House and Senate press galleries: Alice Allison Dunnigan (See also: 1948)

1948

[edit]- First African-American man to receive an Oscar: James Baskett (Honorary Academy Award for his portrayal of "Uncle Remus" in Disney's Song of the South, 1946)[178] (See also: Sidney Poitier, 1964)

- First African-American on an Olympic basketball team and first African-American Olympic gold medal basketball winner: Don Barksdale, in the 1948 Summer Olympics

- First African-Americans to play in the Cotton Bowl Classic: Wallace Triplett and Dennis Hoggard[179]

- First African American to design and construct a professional golf course: Bill Powell

- First African-American knowingly trained and commissioned as a U.S. Naval aviator: Jesse L. Brown[180]

- First African-American composer to have an opera performed by a major U.S. company: William Grant Still (Troubled Island, New York City Opera)[181]

- First African-American woman to win an Olympic gold medal: Alice Coachman[182]

- First African-American since Reconstruction to enroll at a traditionally white university of the South: Silas Hunt (University of Arkansas Law School)[183][Note 11]

- First known African-American star of a regularly scheduled network television series: Bob Howard, The Bob Howard Show[155][185][186][Note 12] (See also: 1956)

- First African-American man to graduate from Oregon State College: William Tebeau[187]

- First African-American female reporter to travel with a U.S. president (Harry S. Truman's election campaign): Alice Allison Dunnigan[171] (See also: 1947)

1949

[edit]- First African-American graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy: Wesley Brown[188]

- First African American to chair a committee of the United States Congress: Representative William Dawson (D-IL).[189]

- First African American to hold the rank of Ambassador of the United States: Edward R. Dudley, ambassador, and previously minister, to Liberia[190] (See also: 1869)

- First African American to win an MVP award in Major League Baseball: Jackie Robinson (Brooklyn Dodgers, National League)[191] (See also: Elston Howard, 1963)

- First African-American-owned and -operated radio station: WERD, established October 3, 1949, in Atlanta, Georgia by Jesse B. Blayton Sr.[192]

- First African-American woman president of an NAACP chapter nationwide: Florence LeSueur of Boston's NAACP chapter.[193]

- First African-American women to earn a doctor of veterinary medicine degree: Jane Hinton and Alfreda Johnson Webb[citation needed]

- First African-American to sing at a U.S. presidential inauguration: Dorothy Maynor

1950s

[edit]1950

[edit]Nat King Cole - First African American to win a Pulitzer Prize: Gwendolyn Brooks (book of poetry, Annie Allen, 1949)[195]

Ralph Bunche - First African American to receive a "lifetime" appointment as federal judge: William H. Hastie, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit[197]

- First African-American woman to compete on the world tennis tour: Althea Gibson[198]

- First African-American solo singer to have a #1 hit on the Billboard charts: Nat King Cole ("Mona Lisa"), topped "Best Sellers in Stores" chart on July 15 (See also: Mills Brothers, 1943; Count Basie, 1947; Tommy Edwards, 1958; The Platters, 1959)[citation needed]

Edith S. Sampson - First African-American NBA basketball players: Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton (New York Knicks), Chuck Cooper (Boston Celtics), and Earl Lloyd (Washington Capitols).[200] Note: Harold Hunter was the first to sign an NBA contract, signing with the Washington Capitols on April 26, 1950.[201][202] However, he was cut from the team during training camp and did not play professionally.[203][Note 13] (See also: 1902)

1951

[edit]- First African-American named to the College Football Hall of Fame: Duke Slater, University of Iowa (1918–1921)[204]

- First African-American quarterback to become a regular starter for a professional football team: Bernie Custis (Hamilton Tiger-Cats)[205]

1952

[edit]

Althea Gibson - First African-American woman elected to a U.S. state senate: Cora Brown (Michigan)[206]

- First African-American U.S. Marine Corps aviator: Frank E. Petersen[207]

- First African-American woman to be nominated for a national political office: Charlotta Bass, Vice President (Progressive Party) (See also: 2000, 2020)[208]

- First African-American baseball player to appear in or win a College World Series: Don Eaddy[209]

1953

[edit]- First African-American basketball player to play in the NBA All-Star Game: Don Barksdale in the 1953 NBA All-Star Game[176]

- First African-American quarterback to play in the National Football League during the modern (post-World War II) era: Willie Thrower (Chicago Bears)[210]

1954

[edit]- First African-American U.S. Navy Diver: Carl Brashear[211]

- First individual African-American woman as subject on the cover of Life magazine: Dorothy Dandridge, November 1, 1954[212]

- First African-American page for the U.S. Supreme Court, and first to be enrolled in the Capitol Page School: Charles V. Bush[213]

1955

[edit]- First African-American member of the Metropolitan Opera: Marian Anderson[214]

- First African-American male dancer in a major ballet company: Arthur Mitchell (New York City Ballet); also first African-American principal dancer of a major ballet company (NYCB), 1956.[215] (See also: 1969)

- First African-American pilot of a scheduled US airline: August Martin (cargo airline Seaboard & Western Airlines)[216][217] (See also: 1964)

Marian Anderson

1956

[edit]- First African-American star of a nationwide network TV show: Nat King Cole of The Nat King Cole Show, NBC (See also: 1948)

- First African American to break the color barrier in a bowl game in the Deep South: Bobby Grier (Pittsburgh Panthers in the 1956 Sugar Bowl)[219]

- First African-American Wimbledon tennis champion: Althea Gibson (doubles, with Englishwoman Angela Buxton); also first African American to win a Grand Slam event (French Open).[220]

- First African-American U.S. Secret Service agent: Charles Gittens[221][222]

- First African American to win the Cy Young Award as the top pitcher in Major League Baseball, in the award's inaugural year: Don Newcombe (Brooklyn Dodgers)[223]

- First African-American woman to become president of a four-year, fully accredited liberal arts college: Willa Beatrice Player (Bennett College)[224]

1957

[edit]- First African-American female Wimbledon Tennis Champion: Althea Gibson

- First African-American assistant coach in the NFL: Lowell W. Perry (See also: 1966)[225]

- First African-American player in the National Hockey League (Made his debut with the Bruins on January 18):Janis F. Kearney

Willie Mays - First African American to work as a botanist at the United States National Arboretum: Roland Jefferson[227]

1958

[edit]- First African-American flight attendant: Ruth Carol Taylor (Mohawk Airlines)[228]

- First African American to reach number-one on the Billboard Hot 100: Tommy Edwards ("It's All in the Game")

1959

[edit]- First African-American Grammy Award winners, in the award's inaugural year: Ella Fitzgerald and Count Basie (two awards each)[229]

Ella Fitzgerald

Count Basie - First African American to win a major national player of the year award in college basketball: Oscar Robertson, USBWA Player of the Year[Note 15] (in that award's inaugural year)

1960s

[edit]- First African American to win the Heisman Trophy: Ernie Davis

- First African American to serve on a U.S. district court: James Benton Parsons, appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois

- First African-American delegate to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Edith S. Sampson (See also: 1950)

- First African American to go over Niagara Falls: Nathan Boya a.k.a. William FitzGerald

- First African American to join the PGA Tour: Charlie Sifford[230]

1962

[edit]

James Meredith - First African-American coach in Major League Baseball: John Jordan "Buck" O'Neil (Chicago Cubs)

- First African-American attorney general of a state: Edward Brooke (Massachusetts) (See also: 1966)

- First African-American student admitted to the University of Mississippi: James Meredith[231]

- First African-American Navy Seal: William Goines[232]

1963

[edit]- First African-American bank examiner for the United States Department of the Treasury: Roland Burris

- First African American to graduate from the University of Mississippi: James Meredith[233]

- First African-American named as Time magazine's Man of the Year: Martin Luther King Jr.[234]

- First African American to win a NASCAR Grand National event: Wendell Scott

- First African-American police officer of the NYPD to be named a precinct commander: Lloyd Sealy, commander of the NYPD's 28th Precinct in Harlem.[99]

Cicely Tyson - First African-American chess master: Walter Harris[235][236]

- First African American to appear as a series regular on a primetime dramatic television series: Cicely Tyson, East Side/West Side (CBS).[237][238]

- First African American to be nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award: Diahann Carroll, for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actress in a Lead Role, for the episode "A Horse Has a Big Head, Let Him Worry" of Naked City (See also: 1968)

- First African-Americans inducted to the Basketball Hall of Fame: New York Renaissance, inducted as a team. (See also: Bob Douglas, 1972; Bill Russell, 1975; Clarence Gaines, 1982)

- First African American to graduate from the U.S. Air Force Academy: Charles V. Bush.

1964

[edit]- First African American to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association: Althea Gibson

- First African-American pilot for a major commercial airline: David E. Harris, American Airlines[239][Note 16] (See also: 1955 and Marlon Green)

- First African-American man to win an Oscar: Sidney Poitier (Best Actor, Lillies of the Field, 1963)

- First movie with African-American interracial marriage: One Potato, Two Potato,[241] actors Bernie Hamilton and Barbara Barrie, written by Orville H. Hampton, Raphael Hayes, directed by Larry Peerce

- First African-American baseball player to be named the Major League Baseball World Series MVP: Bob Gibson, St. Louis Cardinals[242]

Shirley Chisholm

1965

[edit]- First African-American nationally syndicated cartoonist: Morrie Turner (Wee Pals)

- First African-American title character of a comic book series: Lobo (Dell Comics).[243][Note 17] (See also: The Falcon, 1969, and Luke Cage, 1972)

- First African-American star of a network television drama: Bill Cosby, I Spy (co-star with Robert Culp)

- First African-American cast member of a daytime soap opera: Micki Grant who played Peggy Nolan Harris on Another World until 1972.

- First African-American Playboy Playmate centerfold: Jennifer Jackson (March issue)

- First African-American U.S. Air Force General: Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr. (Three-star General)

Patricia Roberts Harris - First African-American NFL official: Burl Toler, field judge/head linesman

- First African American to win a national chess championship: Frank Street Jr. (U.S. Amateur Championship)[244]

- First African-American United States Solicitor General: Thurgood Marshall (See also: 1967)

- First African American woman to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from Yale Law School: Pauli Murray

1966

[edit]- First African-American man to be nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award and first African American to win a Primetime Emmy Award: Bill Cosby, I Spy

- First team with five African-American starters to win the NCAA basketball tournament: 1965–66 Texas Western Miners basketball team

- First African-American coach in the National Basketball Association: Bill Russell (Boston Celtics)

- First African-American (mixed-race) model on the cover of a Vogue (British Vogue) magazine: Donyale Luna

- First post-Reconstruction African-American elected to the U.S. Senate (and first African-American elected to the U.S. Senate by popular vote): Edward Brooke (Republican; Massachusetts) (See also: 1962)

- First African-American Cabinet secretary: Robert C. Weaver (Department of Housing and Urban Development)

- First African-American Major League Baseball umpire: Emmett Ashford

- First African-American NFL broadcaster: Lowell W. Perry[citation needed] (CBS, on Pittsburgh Steelers games) (See also: 1957)

Bill Russell - First African-American mayor in Ohio: Robert C. Henry of Springfield, Ohio.

1967

[edit]- First African American to win a PGA Tour event: Charlie Sifford (1967 Greater Hartford Open Invitational)

- First African-American elected mayor of a large U.S. city: Carl B. Stokes (Cleveland, Ohio)

- First African-American appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States: Thurgood Marshall (See also: 1965)

- First African-American selected for astronaut training: Robert Henry Lawrence Jr.

- First African American to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame: Emlen Tunnell

Thurgood Marshall

1968

[edit]- First African-American interracial kiss on a network television drama: Uhura, played by Nichelle Nichols (African-American) and Captain Kirk, played by William Shatner (Jewish-Canadian): Star Trek: "Plato's Stepchildren" (See also: 1967)

- First African-American man to win a Grand Slam tennis event: Arthur Ashe (US Open) (See also: Althea Gibson, 1956; Serena Williams, 2003)

- First African-American coach to win an NBA Championship: Bill Russell

- First African-American to serve as an executive of the United Methodist Publishing House: W. T. Handy Jr.

- First African-American woman elected to U.S. House of Representatives: Shirley Chisholm (New York)

- First African-American appointed as a United States Assistant Secretary of State: Barbara M. Watson

- First African American to start at quarterback in the modern era of professional football: Marlin Briscoe (Denver Broncos, AFL)

- First African-American commissioned officer awarded the Medal of Honor: Riley L. Pitts

- First fine-arts museum devoted to African-American work: Studio Museum in Harlem

- First African-American actress to star in her own television series where she did not play a domestic worker: Diahann Carroll in Julia (see also: 1963)

- First African-American woman as a presidential candidate: Charlene Mitchell (See also: Shirley Chisholm, 1972)

- First African-American woman reporter for The New York Times: Nancy Hicks Maynard

- First African-American starring character of a comic strip: Danny Raven in Dateline: Danger! by Al McWilliams and John Saunders.[246][247]

1969

[edit]- First African-American superhero: The Falcon, Marvel Comics' Captain America #117 (September 1969).[248][Note 17] (See also: Lobo, 1965 and Luke Cage, 1972)

- First African-American graduate of Harvard Business School: Lillian Lincoln

Gordon Parks - First African-American founder of a classical training school and the company of ballet: Arthur Mitchell, Dance Theatre of Harlem (See also: 1955)

- First African-American woman to appear on the Grand Ole Opry: Linda Martell

- First African American to own a commercial airliner: Warren Wheeler (Wheeler Airlines)[249]

1970s

[edit]1970

[edit]- First African American to head an Episcopal diocese: John Melville Burgess, diocesan bishop of Massachusetts[250]

- First African-American U.S. Navy Master Diver: Carl Brashear (See also: 1954; 1968)

- First African-American member of the New York Stock Exchange: Joseph L. Searles III[251]

- First African-American NCAA Division I basketball coach: Will Robinson (Illinois State University)[Note 18]

- First African-American contestant in the Miss America pageant: Cheryl Browne (Miss Iowa)

- First African-American woman (and first woman) to become a physician's assistant: Joyce Nichols

- First African-American actress to win a Emmy Award: Gail Fisher for Mannix (see also: 1971)

- First African-American basketball player to win the NBA All-Star MVP, the NBA Finals MVP, and the NBA MVP all in the same season: Willis Reed (New York Knicks)

- First African American to initiate the concept of free agency. He refused to accept a trade following the 1969 season, ultimately appealing his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The trend of free agency expanded across the entire landscape of professional sports for all races and all cultures: Curt Flood (St. Louis Cardinals)[Note 19]

- First African American to become director of a major library system in America: Clara Stanton Jones, as director of the Detroit Public Library[252]

- First African American to perform at a Super Bowl halftime show: Lionel Hampton (Super Bowl IV)

1971

[edit]- First African-American pitcher to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame: Satchel Paige (See also: Jackie Robinson, 1962)

- First African-American president of the New York City Board of Education: Isaiah Edward Robinson Jr.

- First African American to win a Golden Globe Award: Gail Fisher for Mannix (see also: 1970)

- First African-American female jockey in the United States: Cheryl White[253]

- First African American to appear by herself on the cover of Playboy: Darine Stern (October issue)

- First African American to become president of the Public Library Association: Effie Lee Morris[254]*1971 DAV Scholarship First African American to receive scholarship to Art Institute of Chicago Mary J. Weatherspoon[tribute 20 years Disable American Veterans Association]

1972

[edit]- First African American to campaign for the U.S. presidency in a major political party and to win a U.S. presidential primary/caucus: Shirley Chisholm (Democratic Party, New Jersey primary) (See also: 1968)

- First African-American superhero to star in own comic-book series: Luke Cage, Marvel Comics' Luke Cage, Hero for Hire #1 (June 1972).[255][Note 17] (See also: Lobo, 1965, and the Falcon, 1969)

- First African-American National Basketball Association general manager: Wayne Embry

- First African-American interracial romantic kiss in a mainstream comics magazine: "The Men Who Called Him Monster", by writer Don McGregor (See also: 1975) and artist Luis Garcia, in Warren Publishing's black-and-white horror-comics magazine Creepy #43 (Jan. 1972) (See also: 1975)[256]

- First African-American interracial male kiss on network television: Sammy Davis Jr. (mixed-race) and Carroll O'Connor (Caucasian) in All in the Family[257]

- First African-American inducted to the Basketball Hall of Fame: Team-owner and coach Bob Douglas, in the category of "contributor" (See also: New York Renaissance, 1963; player Bill Russell, 1975; coach Clarence Gaines, 1982)

- First African-American female Broadway director: Vinnette Justine Carroll (Don't Bother Me, I Can't Cope)

- First African-American comic-book creator to receive a "created by" cover-credit: Wayne Howard (Midnight Tales #1)

1973

[edit]- First African-American artistic director of a professional regional theater: Harold Scott (Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park)

- First African-American Bond villain in a James Bond movie: Yaphet Kotto, playing Mr. Big/Dr. Kananga, Live and Let Die.

- First African-American Bond Girl in a James Bond movie: Gloria Hendry (playing Rosie Carver), Live and Let Die.

- First African-American elected mayor of Los Angeles: Tom Bradley

- First African-American psychologist in the U.S. Air Force: John D. Robinson

Doris A. Davis - First African-American woman adult film star, Desiree West.[258]

1974

[edit]- First African-American model on the cover of U.S. Vogue magazine: Beverly Johnson

- First African-American NBA Coach of the Year: Ray Scott (Detroit Pistons)

- First African-American woman to serve as a United States Secret Service agent: Zandra Flemister[259]

1975

[edit]

Walter Washington - First African-American game show host: Adam Wade (CBS' Musical Chairs)

- First African-American four-star general: Daniel James Jr.

- First African-American inducted to the Basketball Hall of Fame as a player: Bill Russell (See also: New York Renaissance, 1963; Bob Douglas, 1972; Clarence Gaines, 1982)

- First African-American interracial couple in a TV-show cast: The Jeffersons, actors Franklin Cover (Caucasian) and Roxie Roker (African-American) as Tom and Helen Willis, respectively; the show's creator: Norman Lear

- First African-American interracial romantic kiss in a full-color comic book: Amazing Adventures #31 (July 1975), feature "Killraven: Warrior of the Worlds", characters M'Shulla Scott and Carmilla Frost, by writer Don McGregor and artist P. Craig Russell[260] (See also: 1972)

- First African-American manager in Major League Baseball: Frank Robinson (Cleveland Indians)

- First African-American model on the cover of Elle magazine: Beverly Johnson

- First African-American psychologist in the U.S. Navy: John D. Robinson

- First African American to play in a men's major golf championship: Lee Elder (The Masters)

- First African American to be named Super Bowl MVP in NFL: Franco Harris (Pittsburgh Steelers). Of mixed ancestry, Harris was also the first Italian-American to win the award.

Franco Harris

Barbara Jordan

1976

[edit]- First African-American female elected officer of an international labor union: Addie L. Wyatt

- First African American to become president of the American Library Association: Clara Stanton Jones, who served as its acting president from April 11 to July 22 in 1976 and then its president from July 22, 1976, to 1977[262]

- First African American to win a major party nomination for statewide office in the Southern United States since the Reconstruction era: Asa T. Spaulding Jr.[263]

- First African-American lawyer from the Deep South to be appointed to the federal judiciary – the United States Military Court of Appeals (now the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces) in Washington, D.C.: Matthew J. Perry

1977

[edit]- First African-American (and first woman), appointed director of the Peace Corps: Carolyn R. Payton

- First African-American drafted to play professional basketball, first woman to dunk in a professional women's game: Cardte Hicks[264]

- First African-American woman in the U.S. Cabinet: Patricia Roberts Harris, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development

- First African-American woman whose signature appeared on U.S. currency: Azie Taylor Morton, the 36th Treasurer of the United States

- First African-American publisher of mainstream gay publication: Alan Bell (Gaysweek)[265][266]

- First African-American woman to join the Daughters of the American Revolution: Karen Batchelor[267]

- First African-American Major League Baseball general manager: Bill Lucas (Atlanta Braves)

- First African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest: Pauli Murray.[268]

- First African-American (half-Latin) woman to work as a registrar for a major scientific museum: Margaret Santiago.[269]

1978

[edit]- First African-American broadcast network news anchor: Max Robinson

- First African-American woman pilot for a major commercial airline: Jill E. Brown, Texas International Airlines[270]

- First African-American woman to advance to the rank of captain in the Navy: Joan C. Bynum[271]

1979

[edit]- First African-American U.S. Marine Corps general officer: Frank E. Petersen

- First African American to win a Daytime Emmy Award for lead actor in a soap opera: Al Freeman Jr. (Ed Hall in One Life to Live)

- First African-American woman ordained in the Lutheran Church in America (LCA), the largest of three denominations that later combined to form the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America: Earlean Miller[272]

Jill E. Brown - First African American to play professional basketball behind the "Iron Curtain", Kent Washington played for KS Start Lublin, Poland.

1980s

[edit]1980

[edit]- First African-American woman to graduate from (and to attend) the U.S. Naval Academy: Janie L. Mines, graduated in 1980[274][275][276]

- First African-American woman to join the cast of NBC's Saturday Night Live: Yvonne Hudson

- First African-American-oriented cable television network: BET[277]

1981

[edit]- First African American to play in the NHL: Val James (Buffalo Sabres)[Note 20]

1982

[edit]- First African-American inducted to the Basketball Hall of Fame as a coach: Clarence Gaines (See also: New York Renaissance, 1963; Bob Douglas, 1972; Bill Russell, 1975)

- First African-American U.S. Army four-star General: Roscoe Robinson Jr.

1983

[edit]- First African-American astronaut: Guion Bluford (Challenger mission STS-8).[278][Note 21]

- First African-American mayor of Chicago: Harold Washington

Vanessa L. Williams - First African-American owners of a major metropolitan newspaper: Robert C. and Nancy Hicks Maynard (Oakland Tribune)

- First African-American admitted on the national level as a member-at-large of the Daughters of the American Revolution: Lena Santos Ferguson

- First African-American artist to have a music video shown in heavy rotation on MTV: Michael Jackson[279]

1984

[edit]- First African American to win a delegate-awarding U.S. presidential primary/caucus: Jesse Jackson (Louisiana, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, Virginia, and one of two separate Mississippi contests).

- First African-American New York City Police Commissioner: Benjamin Ward

- First African-American coach to win the NCAA Division I Men's Basketball Championship: John Thompson (Georgetown)

1985

[edit]- First African American to become a member of the U.S. Navy's Blue Angels precision flying team: Donnie Cochran. Also first African American to command the team (1994).

- First African-American (mixed-race) female general: Sherian Cadoria

1986

[edit]

Willy T. Ribbs - First African-American musicians inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in the inaugural class: Chuck Berry, James Brown, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Fats Domino, and Little Richard

- First African-American woman (Shirley A. Ajayi) was given a part for 6 months on a TV show as a psychic in 1986 in Chicago, Illinois. Shirley had to audition with other psychics to get the part. She then was taught marketing at the John Hancock center by her boss who ran the TV show. For safety reasons she was renamed as "Aura!". Bio available-book: "Aura The Ebony Princess."

1987

[edit]- First African-American woman, and first woman, inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: Aretha Franklin

- First African-American Radio City Music Hall Rockette: Jennifer Jones

- First African-American man to sail around the world solo: Teddy Seymour

- First African-American CEO of a Fortune 500 company: Clifton R. Wharton Jr.[280]

- First African-American woman, and first woman, to have an album debut at number one on the Billboard 200: Whitney Houston

1988

[edit]- First African American to win a medal at the Winter Olympics (a bronze in figure skating): Debi Thomas

- First African-American woman elected to a U.S. judgeship, and first appointed to a state supreme court: Juanita Kidd Stout

- First African-American candidate for President of the United States to obtain ballot access in all 50 states: Lenora Fulani

- First African-American NFL referee: Johnny Grier

- First African-American quarterback to start (and to win) a Super Bowl: Doug Williams (Super Bowl XXII)

1989

[edit]- First African-American NFL coach of the modern era: Art Shell, Los Angeles Raiders

- First African-American mayor of New York City: David Dinkins

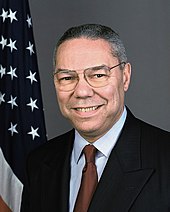

- First African-American Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: Colin Powell

Ron Brown - First African-American Chairman of the Democratic National Committee: Ron Brown[281]

1990s

[edit]1990

[edit]- First elected African-American governor: Douglas Wilder (Virginia) (See also: P. B. S. Pinchback, 1872)

- First African-American elected president of the Harvard Law Review: Barack Obama[282] (See also: 2008, 2009)

- First African-American Miss USA: Carole Gist

- First African-American Playboy Playmate of the Year: Renee Tenison

1991

[edit]- First African American to qualify for the Indianapolis 500 auto race: Willy T. Ribbs (See also: Ribbs, 1986)

- First African-American female mayor of Washington, D.C.: Sharon Pratt Kelly

1992

[edit]- First African-American female astronaut: Dr. Mae Jemison (Space Shuttle Endeavour)

- First African-American woman elected to U.S. Senate: Carol Moseley Braun (Illinois)

- First African-American woman to moderate a Presidential debate: Carole Simpson (second debate of 1992 campaign)

- First African American to sail solo around the world following the Age of Sail route around the southern tips of South America (Cape Horn) and Africa (Cape of Good Hope), avoiding the Panama and Suez Canals: Bill Pinkney[283]

- First African-American Major League Baseball manager to reach (and win) the World Series: Cito Gaston (Toronto Blue Jays) 1992 World Series

- First African American to direct an animated film: Bruce W. Smith (Bebe's Kids)

1993

[edit]- First African-American United States Secretary of Commerce: Ron Brown

Hazel O'Leary - First African American to win the Nobel Prize for Literature: Toni Morrison

- First African-American woman named Poet Laureate of the United States: Rita Dove; also the youngest person named to that position

- First African-American appointed Director of the National Drug Control Policy: Lee P. Brown

- First African-American Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: David Satcher[284]

- First African-American appointed Surgeon General of the United States: Joycelyn Elders

- First African American to serve as home plate umpire for World Series game: Charlie Williams for Game 4 of the 1993 World Series

Charley Pride

1994

[edit]- First African-American female director of a major-studio movie: Darnell Martin (Columbia Pictures' I Like It Like That)

- First African-American (mixed-race) to win the United States Amateur Championship: Tiger Woods[Note 23]

1995

[edit]- First African-American inductee to the National Radio Hall of Fame: Hal Jackson

- First African-American Sergeant Major of the Army: Gene C. McKinney

- First African-American Miss Universe: Chelsi Smith

- First African-American personal diarist to a U.S. president (Bill Clinton): Janis F. Kearney[286]

1996

[edit]

J. Paul Reason - First African-American MLB general manager to win the World Series: Bob Watson (New York Yankees), 1996 World Series

1997

[edit]- First African-American (mixed-race) to win a men's major golf championship: Tiger Woods (The Masters)[Note 23]

- First African-American model to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Edition: Tyra Banks

- First African-American UFC champion: Maurice Smith

- First African-American Director of the National Park Service: Robert Stanton[288]

1998

[edit]- First African-American appointed U.S. Secretary of Labor: Alexis Herman\

Tiger Woods

Robert Stanton - First African-American (mixed-race) to play in the Presidents Cup: Tiger Woods[Note 23]

- First African American to lie in honor at the U.S. Capitol: Jacob Chestnut[289][290] (See also: 2005, 2019)

- First African-American Space Shuttle Commander Frederick D. Gregory

1999

[edit]- First African American to be awarded the Grandmaster title in chess: Maurice Ashley[291][better source needed]

- First African-American Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps: Alford L. McMichael

Shirley Ann Jackson

21st century

[edit]2000s

[edit]2000

[edit]- First African-American nominated for Vice President of the United States by a Federal Election Commission-recognized and federally funded political party: Ezola B. Foster (See also: 1952, 2020; FEC established in 1975)

- First African American to be inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame: Charley Pride[293]

- First African American to be elected Republican state party chair in the United States: Michael Steele[294]

2001

[edit]

- First African-American (mixed-race) Secretary of State: Colin Powell

- First African-American president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops: The Most Reverend Wilton Daniel Gregory (see also: 2020)

- First African-American president of the Unitarian Universalist Association: Rev. William G. Sinkford

- First African-American president of an Ivy League university: Ruth J. Simmons at Brown University

- First African-American woman and first woman National Security Advisor: Condoleezza Rice (See also: 2005)

- First African-American billionaire: Robert L. Johnson, founder of Black Entertainment Television (See also: 2002)

- First African-American woman billionaire: Sheila Johnson

- First African-American broadcaster to call a Super Bowl: Greg Gumbel (Super Bowl XXXV)

2002

[edit]- First African American to become majority owner of a U.S. major sports league team: Robert L. Johnson (Charlotte Bobcats, NBA)[Note 24] (See also: 2001)

- First African-American Winter Olympic gold medal winner: Vonetta Flowers (two-woman bobsleigh)

- First African-American woman combat pilot in the U.S. Armed Forces: Captain Vernice Armour, USMC (See also: 2008)

- First African-American (half-Caucasian) to win an Oscar: Halle Berry (Best Lead Actress, Monster's Ball, 2001)

- First African-American to receive the EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony Awards): Whoopi Goldberg[295]

- First African-American woman to be ranked #1 in tennis: Venus Williams

- First African American to be named year-end world champion by the International Tennis Federation: Serena Williams

- First African-American Arena Football League head coach to win ArenaBowl: Darren Arbet (San Jose SaberCats), ArenaBowl XVI

Condoleezza Rice

2003

[edit]- First African American to win a Career Grand Slam in tennis: Serena Williams (See also: Althea Gibson, 1956; Arthur Ashe, 1968)

- First African-American American Bar Association president: Dennis Archer[296]

Michael Steele

2004

[edit]- First African-American inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame: Charlie Sifford

- First African-American NBA general manager to win the NBA Finals: Joe Dumars (Detroit Pistons), 2004 NBA Finals

- First African-American Canadian Football League head coach to reach (and win) the Grey Cup: Pinball Clemons (Toronto Argonauts), 92nd Grey Cup

2005

[edit]- First African-American woman Secretary of State: Condoleezza Rice (See also: 2001)

- First African-American women to lead a major transportation agency in the U.S. serving on the BART Board of Directors: Carole Ward Allen and Lynette Sweet[297]

Venus and Serena Williams - First African-American woman (and first woman), to lie in honor at the U.S. Capitol: Rosa Parks[298][290] (See also: 1998, 2019)

2006

[edit]- First African American to command a United States Marine Corps division: Major General Walter E. Gaskin

- First African-American individual Winter Olympic gold medal winner: Shani Davis (men's 1,000-meter speed skating)

- First African American to reach the peak of Mount Everest: Sophia Danenberg

- First African-American woman to receive Dharma transmission in Zen Buddhism: Merle Kodo Boyd[299]

- First African-American quarterback inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame: Warren Moon

- First African-American Lady of Turks and Caicos Islands: LisaRaye McCoy

2007

[edit]- First known African-American woman to reach the North Pole: Barbara Hillary[300]

- First African-American White House Chief Usher: Stephen Rochon[301]

- First African-American NFL head coaches to reach the Super Bowl: Lovie Smith and Tony Dungy, Super Bowl XLI[Note 25]

Tony Dungy

2008

[edit]- First African American to be nominated as a major-party U.S. presidential candidate: Barack Obama, Democratic Party[302]

- First African-American elected President of the United States: Barack Obama[303]

- First African American First Lady: Michelle Obama

- First African American to referee a Super Bowl game: Mike Carey (Super Bowl XLII)

- First African-American woman elected Speaker of a state House of Representatives: California Rep. Karen Bass

- First African American to be appointed to the United States Senate by a state governor: Roland Burris

- First African-American woman combat pilot in the United States Air Force: Major Shawna Rochelle Kimbrell (See also: 2002)

Michelle Obama

2009

[edit]

- First African-American President of the United States: Barack Obama

- First African-American First Lady of the United States: Michelle Obama

- First African-American chair of the Republican National Committee: Michael Steele

- First African-American United States Attorney General: Eric Holder

- First African-American woman United States Ambassador to the United Nations: Susan Rice

- First African-American United States Trade Representative: Ron Kirk

- First African-American woman Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency: Lisa P. Jackson

- First African-American White House Social Secretary: Desirée Rogers

- First African American to appear by himself on a circulating U.S. coin: Duke Ellington (District of Columbia quarter).[304]

- First African-American Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Charles F. Bolden Jr.

- First African-American woman rabbi: Alysa Stanton[305][306]

- First African-American woman CEO of a Fortune 500 company: Ursula Burns, Xerox Corporation.

- First African-American doubles team to be named year-end world champion by the International Tennis Federation: Serena and Venus Williams

2010s

[edit]2010

[edit]- First African-American female to be elected state Attorney General in the United States: Kamala Harris (California) (See also: 2020 and 2021)

- First African American to win the Stanley Cup: Dustin Byfuglien with the Chicago Blackhawks[307]

2011

[edit]- First African-American Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons: Charles E. Samuels Jr.[308]

- First African-American admitted to the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College: Sandra Lawson[309][310]

- First African-American woman to serve as acting chair of the Democratic National Committee: Donna Brazile

2012

[edit]- First African American to be re-elected President of the United States: Barack Obama[311]

- First African-American Combatant Commander of United States Central Command: Lloyd Austin[312]

- First African-American elected president of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC): Fred Luter[313][314]

- First African-American woman to take command of a navy missile destroyer: Monika Washington Stoker[315]

2013

[edit]- First African-American U.S. senator from the former Confederacy since Reconstruction: Tim Scott[316]

- First African-American president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Cheryl Boone Isaacs[317]

- First African-American United States Secretary of Homeland Security: Jeh Johnson[318]

- First African-American to receive a full-length statue in the United States Capitol: Rosa Parks[319]

2014

[edit]- First African-American woman four-star admiral: Michelle J. Howard[320]

- First African-American senator to be elected in the South since Reconstruction: Tim Scott, elected in South Carolina[321]

- First African-American player named to the USA Curtis Cup Team: Mariah Stackhouse[322][323]

- First African-American transgender woman to appear on the cover of Time magazine: Laverne Cox[324]

2015

[edit]- First African American to lead a major intelligence agency: Vincent R. Stewart, Defense Intelligence Agency[325]

- First African-American commissioner of a major North American sports league: Jeffrey Orridge, Canadian Football League[326]

- First African-American woman Attorney General of the United States: Loretta Lynch[327]

Misty Copeland - First African American to be inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame: Wendell Scott[329] (See also: 1952)

- First African-American sole anchor of a network evening newscast: Lester Holt[330]

- First African-American elected as presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church: Bishop Michael Curry[331]

- First African-American female American Bar Association president: Paulette Brown[332]

2016

[edit]- First African-American president of a major broadcast TV network: Channing Dungey

- First African-American Librarian of Congress: Dr. Carla Hayden[333]

2017

[edit]- First African-American CEO of a Major League Baseball team: Derek Jeter[334]

- First African-American to win the University of Mary Washington Historic Preservation Book Prize: Catherine Fleming Bruce[335]

2018

[edit]

Carla Hayden - First African American to play for Team USA Hockey in the Olympic Games: Jordan Greenway

- First African-American artist commissioned for U.S. president portrait to be displayed in the Smithsonian: Kehinde Wiley

- First African-American artist commissioned for U.S. first lady portrait to be displayed in the Smithsonian: Amy Sherald

- First African-American elected to a state office of the Maryland Society Daughters of the American Revolution: Reisha Raney

- First African American to be the artistic or creative director of a French fashion house: Virgil Abloh[336]

- First African-American president of the American Psychiatric Association: Altha Stewart[337]

- First African-American woman to be major party nominee for state governor: Stacey Abrams[338]

- First African-American superintendent of the United States Military Academy: Darryl A. Williams[339]

- First African-American woman U.S. Marine Corps general officer: Lorna Mahlock

Jordan Peele

2019

[edit]- First African-American woman to be the director of the Illinois Department of Public Health: Dr. Ngozi Ezike[341]

- First African-American general authority of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Peter M. Johnson

- First African-American (and first historian) secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: Lonnie Bunch[342]

- First African-American female director of an Association of Zoos and Aquariums-accredited institution: Denise Verret[343]

- First African-American elected official to lie in state at the U.S. Capitol: Representative Elijah Cummings[344][345] (See also: 1998, 2005)

- First African-American elected to the National Board of Management of the Daughters of the American Revolution: Wilhelmena Rhodes Kelly

2020s

[edit]2020

[edit]

- First African-American (and Asian-American) to be nominated as a major party U.S. vice-presidential candidate: Kamala Harris, Democratic Party (See also: 2010 and 2021)[346][347]

- First African-American and first female elected Vice President of the United States: Kamala Harris[348]

- First African American to be appointed as a military Chief of Staff and first African American to lead any branch of the United States Armed Forces: Charles Q. Brown Jr.

- First African-American woman elected to the Raleigh City Council: Stormie Forte

- First African-American president of an NFL team: Jason Wright (Washington Commanders)[349][350]

- First African-American Professor of Poetry, first African-American woman Professor and first Distinguished Visiting Poetry Professor of the Iowa Writers' Workshop: Tracie Morris[351]

- First African-American elected official to lie in state at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda: John Lewis[345] (See also: 1998, 2005)

- First African-American Catholic cardinal: Wilton Gregory[352] (see also: 2001)

2021

[edit]- First African-American (and Asian-American) and first female Vice President of the United States: Kamala Harris (See also: 2010 and 2020)

- First African-American (and Asian-American) and first female President of the United States Senate: Kamala Harris

- First African-American (and Asian-American) and first female to serve as Acting President of the United States: Kamala Harris

- First African-American Democratic U.S. senator to represent a former Confederate state in the United States Senate: Raphael Warnock, elected in Georgia.[353][354][355]

- First African-American United States Secretary of Defense: Lloyd Austin[356]

- First full-time female African-American NFL coach: Jennifer King (Washington Commanders).[357]

- First African-American president of the American Civil Liberties Union: Deborah Archer[358]

- First African-American woman to serve on the Supreme Court of Missouri: Robin Ransom[359]

- First African-American woman to appear on the Maxim magazine and became "Sexiest Woman Alive": Teyana Taylor

- First African American to win the Scripps National Spelling Bee: Zaila Avant-garde[360]

- First African-American U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York: Damian Williams[361]

- First African-American NCAA ice hockey coach: Kelsey Koelzer[362]

- First African-American Connecticut State Comptroller: Natalie Braswell[363]

- First African-American woman to be elected as Lieutenant Governor of Virginia: Winsome Sears

- First African-American to be elected as Lieutenant Governor of North Carolina: Mark Robinson

- First African-American to serve as Second Lady of North Carolina: Yolanda Hill Robinson

2022

[edit]- First Afro-Caribbean American woman elected Speaker of the New York City Council: Adrienne Adams[364]

- First African-American woman and first woman to be the police commissioner of the New York Police Department: Keechant Sewell[365]

- First African-American woman to appear on U.S. currency (a quarter): Maya Angelou[366]

- First African-American woman nominated, confirmed to, and sworn into the Supreme Court of the United States: Ketanji Brown Jackson[367]

- First African-American represented in the National Statuary Hall Collection: Mary McLeod Bethune[368][369]

- First African-American Marine Corps four-star general: Michael Langley[370]

- First African-American elected governor of the U.S. state of Maryland: Wes Moore[371]

- First African-American elected Attorney General of the U.S. state of Maryland: Anthony Brown[372]

- First African-American chosen to lead a party caucus in either chamber of Congress: Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY)[373][374]

- First African-American female Major general in the United States Marine Corps: Lorna Mahlock[375][376]

- First African-American woman to join the Arkansas Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution: Sharon Fort[377]

- First African-American transgender woman model for Victoria's Secret: Emira D'Spain[378]

- First African-American woman elected mayor of Los Angeles: Karen Bass[379]

- First African-American woman to win 32 Grammy Awards: Beyoncé

2023

[edit]

- First openly LGBT African-American to serve in the United States Senate: Laphonza Butler[380]

- First African-American woman elected Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives: Joanna McClinton[381]

2024

[edit]

- First African-American (and Asian-American) female to be nominated as a major party U.S. presidential candidate: Kamala Harris, Democratic Party[382]

- First African-American descendent of Colonel John Hazzard Carson admitted to the Daughters of the American Revolution and first African-American member of the NSDAR Greenlee Chapter: Regina Lynch-Hudson

See also

[edit]- List of African-American pioneers in desegregation of higher education

- List of African-American sports firsts

- List of African-American arts firsts

- List of African-American United States Cabinet members

- List of African-American U.S. state firsts

- List of black Academy Award winners and nominees

- List of black Golden Globe Award winners and nominees

- List of first African-American mayors

- List of African-American women in medicine

- Timeline of African-American history

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- List of Asian-American firsts

- List of Native American firsts

Notes

[edit]- ^ This claim is contested by the First Baptist Church, Petersburg, Virginia (1774) and the First Colored Baptist Church, renamed First African Baptist Church, Savannah, Georgia (recognized 1788, first congregation 1773).