An Open Letter to Hobbyists

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Companies Charitable organizations Writings | ||

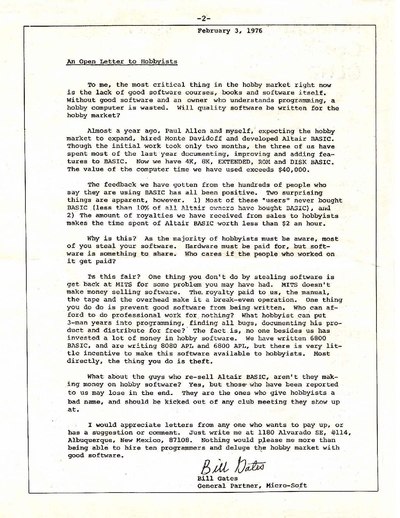

"An Open Letter to Hobbyists" is a 1976 open letter written by Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, to early personal computer hobbyists, in which Gates expresses dismay at the widespread duplication of software taking place in the hobbyist community, particularly with regard to his company's software.

In the letter, Gates expressed frustration with most computer hobbyists who were using his company's Altair BASIC software without having paid for it. He asserted that such widespread use of his software in effect discouraged developers from investing time and money in creating high-quality software. He cited the unfairness of gaining the benefits of software authors' time, effort, and capital without paying them as a rationale for refusing to publish the source code for his company's flagship product, thereby making it unavailable to lower-income hobbyists who could have borrowed such program blueprints from their local library and entered the program into their hobby computer by data entry.

Altair BASIC

[edit]

In December 1974, Gates, a student at Harvard University, alongside Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who worked at Honeywell in Boston, both saw the Altair 8800 computer in the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics for the first time. They had both written BASIC language programs since their days at Lakeside School in Seattle, and knew the Altair computer was powerful enough to support a BASIC interpreter.[a] Both Gates and Allen wanted to be the first to offer BASIC for the Altair computer, and expected the software development tools they had previously created for their Intel 8008 microprocessor-based Traf-O-Data computer to give them a head start.[1]

By early March of the following year, Allen, Gates and Monte Davidoff, a fellow Harvard student, had created a BASIC interpreter that worked under simulation on a PDP-10 mainframe computer at Harvard. Allen and Gates had been in contact with Ed Roberts of MITS, and in March 1975, Allen visited Albuquerque, New Mexico, to test the software on an actual machine. To both Allen and Roberts' surprise, the software worked.[2] MITS agreed to license the software from Allen and Gates. Allen left his job at Honeywell, and became the Vice President and Director of Software at MITS with a salary of $30,000 (equivalent to $175,306 in 2024) a year;[b][4] Gates remained a student at Harvard, and worked under MITS as a contractor instead, with the October 1975 company newsletter giving his title at the company as "Software Specialist".[5]

On July 22, 1975, MITS signed the contract with Allen and Gates, who would receive $3000 at the signing and a royalty for each copy of BASIC sold; $30 for the 4K version, $35 for the 8K version and $60 for the expanded version. The contract had a cap of $180,000, with MITS retaining an exclusive worldwide license to the program for 10 years. MITS would supply the computer time necessary for development on a PDP-10 owned by the Albuquerque school district.[6]

The April 1975 issue of MITS's Computer Notes had the banner headline "Altair Basic – Up and Running". The Altair 8800 computer was a break-even sale for MITS, who would need to sell additional memory boards, I/O boards, and other add-on options to make a profit. When purchased with two 4K memory boards and an I/O board, the 8K BASIC cost just $75, the initial standalone price for BASIC being $500.[clarification needed] To promote the computer, MITS purchased a camper van and outfitted it with the complete product line, dubbed the "MITS-Mobile"; the company used this van to tour the United States, giving seminars featuring the Altair Computer and Altair BASIC.

1975 Homebrew Computer Club and subsequent copying of Altair BASIC

[edit]The Homebrew Computer Club was an early computer hobbyist club in Palo Alto, California. At the first meeting in March 1975, Steve Dompier gave an account of his visit to the MITS factory in Albuquerque, where he had attempted to pick up his order for one of everything.[7] He left with a computer kit with 256 bytes of memory. At the April 16, 1975 club meeting, Dompier keyed in a small program that played the song "The Fool on the Hill" on a nearby AM radio, through the use of radio frequency interference or static controlled by the timing loops in the program.[8] Gates, who could not figure out how the computer could broadcast to the radio, described this in the July 1975 edition of Computer Notes as "the best demo program I've seen for the Altair".[9]

The June 1975 Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter carried this item written by Fred Moore, Editor:

The MITS MOBILE came to Rickey's Hyatt House in Palo Alto June 5th & 6th. The room was packed (150+) with amateurs and experimenters eager to find out about this new electronic toy.[10]

At the same June seminar, a paper tape containing a pre-release version of Altair BASIC disappeared. The tape was given to Dompier, who passed it on to Dan Sokol, who had access to a high speed tape punch. At the next Homebrew Computer Club meeting, 50 copies of Altair BASIC on paper tape appeared in a cardboard box.[11]

MITS offered a complete Altair system with two MITS 4K Dynamic RAM boards, a serial interface board and Altair BASIC for $995.[12] However, the $264 MITS RAM boards were unreliable, due to several component and design problems. An enterprising Homebrew Computer Club member, Robert Marsh, designed a 4K static memory that was plug-in compatible with the Altair 8800, and sold it for $255.[13] His company, Processor Technology, became one of the most successful Altair compatible board suppliers. As a result of Dompier's copying of Altair BASIC and Marsh's third-party 4K static memory plug-in, many Altair 8800 computer owners came to skip purchasing the bundled package from MITS directly, instead purchasing their memory boards from a third-party supplier and using a "borrowed" copy of Altair BASIC.

Ed Roberts acknowledged the 4K Dynamic RAM board problems in the October 1975 Computer Notes. The price was reduced from $264 to $195, and existing purchasers got a $50 rebate; the full price for 8K Altair BASIC was reduced to $200, though Roberts declined a customer's request that MITS give BASIC to customers for free, noting that MITS had made a "$180,000 royalty commitment to Micro Soft". Roberts also wrote that "Anyone who is using a stolen copy of MITS BASIC should identify himself for what he is, a thief", and described third-party hardware suppliers as "parasite companies".[14] The newly released Processor Technology static RAM board drew more current than the MITS dynamic RAM board, with the addition of two or three boards taxing the Altair 8800's power supply. As a consequence, Howard Fullmer began selling a power supply upgrade for the Altair, naming his company Parasitic Engineering as a nod to Roberts' comments.[15][c] Fullmer would later help define the industry standard for Altair compatible boards, the S-100 bus standard.[17] The next year, 1976, would see many Altair bus computer clones such as the IMSAI 8080 and the Processor Technology Sol-20.

Open letter

[edit]

At the end of 1975, MITS was shipping a thousand computers a month, but copies of BASIC were selling in the low hundreds.[18] Additional software projects[vague] required more resources; the MITS 8-inch floppy disk system was about to be released, as was the MITS 680B computer based on the Motorola 6800. A high school friend of Allen and Gates, Ric Weiland, was hired to convert the 8080 BASIC to the 6800 microprocessor. David Bunnell, Computer Notes Editor, was sympathetic to Gates' position. He wrote in the September 1975 issue that "customers have been ripping off MITS software".

Now I ask you--does a musician have the right to collect the royalty on the sale of his records or does a writer have the right to collect the royalty on the sale of his books? Are people who copy software any different than those who copy records and books?[19]

Gates, keen to attempt to explain the cost of developing software to the hobbyist community, restated much of what Bunnell had written in September and what Roberts had written in October; however, the tone of his letter was different, instead emphasising Gates' view that hobbyists were stealing from him personally, and not from a corporation.

Why is this? As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?

One of the principal targets of the letter was the Homebrew Computer Club, with a copy sent to the club directly. The letter also appeared in Computer Notes. To ensure the letter would be noticed, Bunnell sent the letter via special delivery mail to every major computer publication in the country.[20]

In the letter, Gates also mentioned the development of the APL programming language for the 8080 and 6800 microprocessors, a programming language in vogue with some other computer scientists in the 1970s. The language, which used a character set based on the Greek alphabet, required special terminals to implement that most hobbyist terminals did not have; as well as not displaying symbols from the Greek alphabet, most hobbyist terminals did not even display lowercase letters. Though Gates was enamored with APL, Allen did not believe it could be sold as a product; interest in the project soon faded, and the software itself was never completed.[21]

Reaction

[edit]

Following the difficulties with receiving piecemeal royalties, Microsoft switched to a fixed-priced contract with MITS, who would pay $31,200 for a non-exclusive license of 6800 BASIC.[22] The future sales of BASIC for the Commodore PET, the Apple II, the Radio Shack TRS-80 and others were all fixed-price contracts.[d]

In early 1976 ads for its Apple I computer, Apple Inc made the claims that "our philosophy is to provide software for our machines free or at minimal cost",[24] emphasising that Apple BASIC was free.[25]

Microsoft's software development was done on a DEC PDP-10 mainframe computer system, with Allen having developed a program that could completely simulate a new microprocessor system. This allowed Microsoft to write and debug software before the new computer hardware was complete. The company was charged by the hour and by the amount of resources (such as storage and printing) used,[citation needed] the "$40,000 of computer time" mentioned in the letter. As a result of these software developments, the 6800 BASIC was complete before the Altair 680 was finished, with the 680 hardware arriving months late.[26]

Hal Singer of the Micro-8 Newsletter published an open letter to Roberts, pointing out that MITS promised a computer for $395, but that the price for a working system was $1000. He suggested a class action lawsuit or a Federal Trade Commission investigation into false advertising was in order. Hal also noted that rumors were circulating that Gates had developed BASIC on a Harvard University computer funded by the US government, and that customers should not pay for software already paid for by the taxpayer.[27] Gates, Allen and Davidoff had used a PDP-10 at Harvard's Aiken Computer Center, the computer system of which had been funded by the Department of Defence through its Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency; Harvard officials were not pleased that Gates and Allen (who was not a student) had used the PDP-10 to develop a commercial product, but determined that the computer itself, which technically belonged to the military, was not covered by any Harvard policy; the PDP-10 was controlled by Professor Thomas Cheatham, who felt that students could use the machine for personal use. Harvard placed restrictions on the computer's use, and Gates and Allen had to use a commercial time share computer in Boston to finalize the software.[28]

In 2008, Homebrew member Lee Felsenstein recalled similar doubts about Gates' $40,000 number: "Well, we all knew [that] the evaluation of computer time was the ultimate in funny money. You never pay that much for the computer time and I think that research will show that they were using someone else's computer time; someone else was paying for that. It could have been Honeywell where Paul Allen was working. So we all knew this to be a spurious argument."[29]

According to Felsenstein, Gates' letter "delineated a rift [between] the actual industry where there's trying to make money and there's those hobbyist where we're trying to make things happen";

The industry needs the hobbyists and this was illustrated by what happened eventually. When National Semiconductor, which made their own microprocessor chips in '77 or '78, decided they needed a BASIC ... they asked, 'What's the most popular BASIC?' And the answer was Microsoft BASIC because everybody had copied it and everybody was using it. So we made Microsoft the standard BASIC. National Semiconductor went to Microsoft and bought a license, they were in business that way. This was the marketing function and the hobbyists did the marketing with a complete antipathy of the company in question. There were other BASICs and, you know, some of them might even have been better. ... [Gates' later success] was in a certain measure because of what we did, that he said we shouldn't do, we were thieves to do it, and all.[29]

There is a viable alternative to the problems raised by Bill Gates in his irate letter to computer hobbyists concerning "ripping off" software. When software is free, or so inexpensive that it's easier to pay for it than to duplicate it, then it won't be "stolen".

Jim Warren, Homebrew Computer Club Member and editor of Dr. Dobb's Journal, wrote in the July 1976 ACM Programming Language newsletter about the successful Tiny BASIC project.[30] The goal was to create BASIC language interpreters for microprocessor based computers. The project had started in late 1975, but the "Open Letter" motivated many hobbyists to participate. Computer clubs and individuals from all parts of the United States and the world soon created Tiny BASIC interpreters for the Intel 8080, the Motorola 6800 and MOS Technology 6502 processors. The assembly language source code was published or the software was sold for five or ten dollars.

Magazines that published the letter

[edit]- Gates, Bill (January 1976). "An Open Letter To Hobbyists". Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter. 2 (1). Mountain View, California: Homebrew Computer Club: 2.

- Gates, Bill (February 10, 1976). "An Open Letter To Hobbyists". Micro-8 Computer User Group Newsletter. 2 (2). Lompoc, California: Cabrillo Computer Center: 1.

- Gates, Bill (February 1976). "An Open Letter To Hobbyists". Computer Notes. 1 (9). Albuquerque, New Mexico: MITS: 3. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- Gates, Bill (March 11, 1976). "An Open Letter to Hobbyists". Minicomputer News. Boston, Massachusetts: Benwill Publishing.

- Gates, Bill (March–April 1976). "An Open Letter To Hobbyists". People's Computer Company. 4 (5). Menlo Park, California.

- Gates, Bill (May 1976). "Computer Hobbyists". Radio-Electronics. Vol. 47, no. 5. New York: Gernsback Publications. pp. 14, 16. Archived from the original on 2019-01-29. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

Several responses to the letter were published, including one from Bill Gates.

- Hayes, Mike (February 1976). "Regarding Your Letter of February 3". Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter. 2 (2). Mountain View, California: Homebrew Computer Club: 2. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- Singer, Harold L. (March 28, 1976). "An Open Letter to Ed Roberts". Micro-8 Computer User Group Newsletter. 2 (4). Lompoc, California: Cabrillo Computer Center: 1.

- Gates, Bill (April 1976). "A Second and Final Letter". Computer Notes. 1 (11). Albuquerque, New Mexico: MITS: 5. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- Childs, Art (May 1976). "Interfacial". SCCS Interface. 1 (6). Los Angeles, California: Southern California Computer Society: 2, 4. Editor Art Childs writes about the letter he received from the "author of Altair Basic" and the resulting controversy on propriety software.

- Wada, Robert (July 1976). "An Opinion on Software Marketing". BYTE. Vol. 1, no. 11. Peterborough, New Hampshire: BYTE Publications. pp. 90, 91.

- Warren, Jim C. (July 1976). "Correspondence". SIGPLAN Notices. 11 (7). ACM: 1. Jim Warren, the editor of Dr. Dobb's Journal, describes how the Tiny BASIC project is an alternative to hobbyist "ripping off" software.

- Moores, Calvin (September 1976). "Are you an author?". BYTE. Vol. 1, no. 13. Peterborough, New Hampshire: BYTE Publications. pp. 18–22. An article on software copyright law that discusses the "Open Letter to Hobbyists".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics was published on November 29, 1974. File:Copyright Popular Electronics 1975.jpg

- ^ Allen would later leave MITS in November of 1976.[3]

- ^ David Ahl describes the assembly of an Altair 8800 system and the various problems that were encountered. The Processor Technology 8K Static RAM (page 94) and the Parasitic Engineering power supply (page 97) are used to replace the MITS components in his system.[16]

- ^ Apple paid $21,000; Radio Shack $50,000; other companies paid roughly $35,000 per license.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ Manes (1994), 68–70.

- ^ Manes (1994), 65–76.

- ^ Manes, pg.103

- ^ Young (1998), 164.

- ^ "Contributors". Computer Notes. 1 (5). Albuquerque NM: MITS: 13. October 1975. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ Manes (1994), 82–83.

- ^ Freiberger (2000), 52–53.

- ^ Dompier, Steve (February 1976). "Music of a sort". Dr. Dobb's Journal. 1 (2). Menlo Park CA: People's Computer Company: 6–7.

- ^ Gates, Bill (July 1975). "Software Contest Winners Announced". Computer Notes. 1 (2). Albuquerque NM: MITS: 1. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ Moore, Fred (June 7, 1975). "It's a Hobby". Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter. 1 (4): 1.

- ^ Manes (1994), 81.

- ^ MITS (August 1975). "Worlds Most Inexpensive BASIC language system". Radio-Electronics. Vol. 46, no. 8. p. 1. MITS advertisement File:Altair Computer Ad August 1975.jpg

- ^ "Hardware". Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter. 1 (5): 2, 5. July 5, 1975.

- ^ Roberts, H. Edward (October 1975). "Letter from the President". Computer Notes. 1 (5). Albuquerque NM.: MITS: 3–4. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ Freiberger (2000), 145–146.

- ^ Ahl, David H.; Burchenal Green (April 1980). "Saga of a System (Building an Altair 8800/Cromemco TV Dazzler system)". The Best of Creative Computing, Volume 3. Morristown NJ: Creative Computing. pp. 90–97. ISBN 0-916688-12-7.

- ^ Morrow, George; Howard Fullmer (May 1978). "Microsystems Proposed Standard for the S-100 Bus Preliminary Specification, IEEE Task 696.1/D2". Computer. 11 (5). IEEE: 84–90. doi:10.1109/C-M.1978.218190. S2CID 2023052.

- ^ Manes (1994), 90.

- ^ Bunnell, David (September 1975). "Across the Editor's Desk". Computer Notes. 1 (4). Albuquerque NM.: MITS: 2. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ Manes (1994), 91.

- ^ Manes (1994), 97–98.

- ^ Manes (1994), 95.

- ^ Manes (1994), Commodore, pg. 105, 111, 114

- ^ "The Apple 1 Project".

- ^ "Apple I Computer Ad". 30 November 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Ed (March 1976). "Ramblings from Ed Roberts". Computer Notes. 1 (10). Albuquerque, NM: MITS: 4. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ Singer, Harold L. (March 28, 1976). "Open Letter to Ed Roberts". Micro-8 Computer User Group Newsletter. 2 (4). Lompoc, CA: Cabrillo Computer Center: 1.

- ^ Wallace (1992), 81–83. "Harvard officials had found out that he (Gates) and Allen had been making extensive use of the university's PDP-10 to develop a commercial product. The officials were not pleased." The computer was funded by the Department of Defense and was under the control of Professor Thomas Cheatham. "Although DARPA was funding the PDP-10 at Harvard, there was no written policy regarding its use. ... After the computer flap, Gates and Allen bought computer time from a timesharing service in Boston to put the finishing touches on their BASIC."

- ^ a b Oral History of Lee Felsenstein Archived 2014-12-27 at the Wayback Machine. Interviewed by Kip Crosby. Computer History Museum 2008, CHM Reference number: X4653.2008

- ^ a b Warren, Jim C. (July 1976). "Correspondence". SIGPLAN Notices. 11 (7). ACM: 1–2. doi:10.1145/987491. ISSN 0362-1340.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ceruzzi, Paul E. (2003). A History of Modern Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53203-4.

- Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

- Manes, Stephen; Paul Andrews (1994). Gates: How Microsoft's Mogul Reinvented an Industry and Made Himself the Richest Man in America. New York: Touchstone, Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-88074-8.

- Wallace, James; Jim Erickson (1992). Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-56886-4.

- Young, Jeffrey S. (1998). Forbes Greatest Technology Stories: Inspiring Tales of the Entrepreneurs. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-24374-4. Chapter 6 "Mechanics: Kits & Microcomputers"

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch